|

|

THE STORY OF OUR VALLEY BY A.B. PERKINS

[PREVIOUS][CONTENTS][SEARCH]6. Oil and Newhall

Oil Replaces Gold

It is of course true that here on Rancho San Francisco, in the canyon of Placeritas, gold mining started in 1842. After the centuries during which gold mining held its place at the top of speculative ventures, it is a positive shock to realize how far that activity has slumped on the economic scale.

To realize that the production and ownership of gold was legislated to a point where even possession of gold coins became a crime, it is even more of a shock to realize that gold, after centuries of economic dominance, was to be replaced by a dirt, sticky, stinking fluid that, not a century back, was wasted from natural seepages that had flowed from earlier geologic periods and had no economic use of importance.

What was Newhall's connection with the foregoing?

Unlike the competition to "The First California Gold Discovery," to which Northern California laid vociferous and popular claim until the early 1930s, Newhall's position in the Western development of the oil industry has always been fully recognized. Here California's oil industry was born.

First Oil Well

Here is the site of historic No. 4, first commercially successful oil well of the West (and CSO No. 4 is on the pump today, producing little oil after more than 75 years of continuous production, but producing).[21] Here was the birthplace of Standard Oil Company of California.

From here Lyman Stewart and Wallace Hardison left for Santa Paula, there to join Thomas Bard in the founding of the Union Oil Company.

At Newhall stands the first successful commercial oil refinery of the West. Here was the first pipeline ever laid for transportation of oil.

Newhall's economy is still largely based upon petroleum, through production, distribution, lease rentals, or royalties.

That last statement may never again be made. The present indication is that our background, too, will shortly be submerged as is evidently to be our destiny.

As this story unfolds, you will become acquainted with a new cast of characters: Sanford Lyon, D.G. Scofield, Lyman Stewart, Charles Youle, "Alex" Mentry, Thomas A. Scott and an industrial romance transcending our local stories from the primitive, to Mission, to Californian, to mining background.

Petroleum Always Here

In truth, "oil" was never "discovered" here. The local seeps in Wiley, Rice, Pico and other canyons had been utilized in prehistoric times by our earliest inhabitants, who had glued their basket hoppers to stone bases with asphalt, whose woven reed bottles had been waterproofed with asphalt. At Santa Barbara the coastal Indian tribes caulked their plank boats with asphalt. Even the lighter oils were used medicinally, internally and externally.

Possibly it was centuries later when Cabrillo reported the Carpenteria beach seepages, when Father Crespi reported the Brea pits in his diary of the Sacred Expedition.

Andres Pico is credited with crudely refining our canyon seepages and using the product as an illuminant at his San Fernando Mission home in 1855. Those seepages continue today, and at the same places. True, it no longer pays to skim them, barrel the scum and ship it coastwise to the gas works at San Francisco, but that is an economic, not a physical, change.

Medicinal Rock Oil

In 1857, George S. Gilbert shipped east kegs of oil which he had distilled from the Sulphur Mountain seepages near Mission San Buenaventura. The kegs were hard to handle via mule back across the Isthmus of Panama and were ditched by the muleteers. That oil was then known as "rock oil," and its only market was medicinal.

"Drake's Well" was completed in Pennsylvania in 1859. The ensuing excitement in the East, for oil then sold at about $1.50 per gallon, very shortly caused the flooding of the market and broke oil prices.

From this slump, the infant industry was saved by the chemists' success in refining a satisfactory illuminant from the oil and thereby expanding the market. (All the industry then had to do was to sell the idea of oil lamps as against candles and camphene whale oil illuminants.)

Pits and Skimming

The mechanics of oil production was still simple. Originally it was produced by skimming seepages. Next, pits to collect the fluid were used as reservoirs. Then someone started small tunnels into the hills to drain seepages into containers. Wells were next, and were dug. Next, from the Chinese, was borrowed the "spring pole" rig wherein a long pole was laid across a crotched pole, a metal bit suspended at one end against a counter-balance at the other end, and the bit teeter-tottered into the ground as the driller, by brute strength, compensated the bit's velocity into the tough earth.

It was during the first oil boom on Oil Creek, in Venango County, Penn., that Thomas A. Scott, then vice-president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and others made a very lucky speculation in the Story Farm purchase, which cost $40,000 and returned more than $1 million in one year. Incidentally, Scott had been considering the possibilities of railroading to the West, and there had been rumors in the East of seepages, similar to those of Venango County, near the California Coast.

Investigation in 1864

It was therefore logical that Scott should retain Prof. Benjamin Silliman Jr., then of Yale University, for examination of such seepage areas near Ventura. Silliman's report, in 1864, said: "The oil is struggling to the surface at every available point, and is running down the river for miles and miles. Artesian wells will be fruitful along a double line of 13 miles, say for at least 25 miles in linear extent. As a ranch it is a splendid estate, but its value is its almost fabulous wealth in the best of oil."

Scott formed corporate set-ups to acquire that "fabulous" oil land — the capitalization was $10 million, one-tenth reserved for working capital (that was before the days of the Securities and Exchange Commission).

Ranch Obtained

The Scott interests purchased 277,000 acres, including the 48,000 acres of Rancho San Francisco.

The following year, Scott's nephew, Thomas A. Bard, arrived in Ventura with drilling equipment, such as it was. From 1866, Bard drilled five wells for too little production. His sixth well, making 15 barrels at 550 feet, was the best, but oil prices dropped.

This was all near Sulphur Mountain back of Santa Paula.

In Los Angeles, at this time, was living Dr. Vincent Gelcich, a one-time Army doctor who had married one of the daughters of Andres Pico. From previous oil experience in Pennsylvania, Dr. Gelcich may have been one of the first to appreciate the oil producing possibilities of Pico Canyon. A small container of the seepage oil was supposed to have been brought to him by Ramon Pereida, on which Dr. Gelcich worked on it as a chemist. Associated with General Andres Pico were Col. Baker, Wiley (another of Pico's sons-in-law) , Leaming, Rice, Todd, Lyon and others. Placer mining claims were filed for the seepages in Pico Canyon in 1865.

Pico Canyon Claimed

Ludwig Louis Salvator, in Los Angeles in the Sunny Seventies, states that the first claim was named Cañada Pico, staked by Andres Pico and later taken over by the California Star Oil Works Co.; the second claim was called Wiley; the third claim, Moore; the fourth claim, Rice, later acquired by Gelcich; the fifth, Leaming; the sixth, Gelcich; and the seventh, Todd.

The Scott interests tried to acquire these claims unsuccessfully in 1867 by attempting to alter the boundary lines of the Rancho San Francisco land grant.

The California oil boom started in 1865. There were 65 wildcat oil companies with nominal capitalization of $45 million.

The company prospectuses were quite optimistic. Shares sold as high as $1,500. One company prospectus claimed that the seepage of oil on its property was so voluminous that cattle were engulfed and drowned.

By 1866 the oil boom — of promotion — was really out of hand. Booms are always paid for by innocent stock investors. This boom was no exception. Booms are always followed by busts.

Scott, primarily top-flight railroader of Pennsylvania, was not encouraged. The results of the Sulphur Mountain drilling were depressing. When they did make a small producer of 10 barrels daily, the price of oil dropped. The apparent petroleum possibilities in Pico Canyon, just outside the Rancho San Francisco boundaries, and their failure to get the lines altered to include the seepage areas, plus the unsound economic conditions following the Civil War — when kerosene fell to 57 cents per gallon, F.O.B. San Francisco, shipped in from the East, and no one had been able to produce it at that price in California — all added to Scott's loss of interest in California petroleum.

First Well in Pico

Early development history of Newhall oil fields, as reported in the Summary of Operations of California Oil Fields, No. 2, Volume 20, by R.J. Walling, says:

The first oil well is credited to Sanford Lyon, who drilled a spring-pole hole 140 feet deep in 1869 near the seepages. There was no further drilling in Pico Canyon until 1875, but the seepage oil was collected and sold to the Polhemus Refinery in Los Angeles and the Metropolitan Gas Works in San Francisco.

The land office records show that five placers were staked in Pico Canyon, the Pico Oil Spring Mine Section Two, R3N 17W, was patented April 19, 1880, to Robert F. Baker and E.F. Beale, two of the remaining placers being patented in 1890 to Occidental Asphalt Co.

W.H. Spangler was superintendent for the Temple oil wells, John Miler was cook, and James Marshall was working on the rig in 1868, for they are so listed in the directory of that date, the wells shown as being seven miles westerly of Lyon Station.

If you will turn off San Fernando Road southerly at Pine Street (between the Southern California Gas Co. and Union Oil plants) just beyond the present Loven Chemical Co. plant, is the road turning into the Standard Oil Co. pumping station. There you can see the oil refinery of the [18]70s, a reconstruction on the original site and with the original equipment.[22] The plaque reads:

California's first oil refinery operates on a commercial scale. Erected 1876-1878.[23] Restored by the Standard Oil Company of California in 1930 as a memorial to D.G. Scofield and his pioneer associates of the California Star Oil Works Company, a predecessor of the Standard Oil Company of California, who procured in 1875-1876 California's first commercial production of crude petroleum in Pico Canyon, six miles northwest of this point and built this refinery for the manufacture of petroleum products.

What a wonderful memorial to a "doer." And how well earned! In 1876, oil was not a quick asset. People were yet to be educated to its use. True, it had entered the illuminating field, but its major competitor, the whales producing whale oil, or the camphene distillers, still had a big advantage.

Speaking vulgarly, our California oil "stunk" unbeatably when burned. Overcoming that handicap took the chemists several years. Another decade would pass before Lyman Stewart and D.G. Scofield would "sell" the local railroads on oil for fuel use. The tribulations to be encountered before shipping would accept the new fuel were both of long duration and painful in the extreme. For in accepting the competition for these two later fields, the infant industry was to buck against the thoroughly entrenched coal industry — and that was to be a battle.

Fishing in 1877

Again quoting from W.E. Youle: "I returned to Pico Canyon in May 1877, to undertake a fishing job on a well started by R. C. McPherson for the San Francisco Oil Company.

"The well might be called a wildcat as it was some considerable distance away from the Pico Canyon producing well — it proved a dry hole and the location was abandoned. Due to this failure of the McPherson Well, ex-mayor Bryant and others withdrew from Pico leaving Scofield the responsibility there."

From which it may be inferred that Scofield's backers backed — out.

The refinery, built for Scofield by his associate, J.A. Scott, of Titusville, Penn., operated until 1888[24], when it was shut down and oil was thereafter shipped in tank cars to the refinery of the Pacific Coast Oil Co. at Alameda. In 1879, a two-inch pipe line was laid from Pico to the local refinery, being the first pipeline of record for transport of oil.

After the failure of the MacPherson Well, Scofield's backers were not inclined to increase their investments which Scofield considered necessary. The question was settled when Scofield interested Senator Charles N. Felton and his associates in the incorporation of the Pacific Coast Oil Co., Sept 1879. Sen. Felton was president, Scofield, auditor, and Lloyd Tevis was among the incorporators. The new company absorbed several small operators, including the California Star Oil Works holdings, although the latter operated as an individual unit.

The Mentry Records

The original data of Charles Alexander Mentry — which, through the courtesy of Walton Young, then the local divisional superintendent of [Standard Oil of] California, I was allowed to copy at the time of the razing of the old Standard warehouse in the early 1930s — indicates the drilling of three spring-pole holes. At 30 feet., CSO No. 1 produced two barrels of oil per day; at 120 feet, production rose to 12 barrels; at 175 feet the well production rose to 30 barrels. Later deepening failed to improve the well.

CSO No. 2 produced six barrels per day at 85 feet, rising to 13 barrels at 140 feet. It operated intermittently due to lack of market. The well was deepened in 1877 and at 250 feet flowed 20 to 25 barrels. At 525 feet, the well pumped 40 barrels. Later deepening in 1882 failed to improve production.

CSO No. 3 pumped four barrels of oil per day at 90 feet, rising to 11 barrels at 170 feet. It was located too closely to No. 1 and No. 2 for deepening.

CSO No. 4 (sometimes called Pico No. 4) started in July 1876 and was completed in September, pumping 25 barrels at 270 feet. In 1877 it was deepened and at 560 feet flowed 70 barrels. This well is supposed to be on the site of Sanford Lyon's first well, and is also the first well to have been drilled by steam. Until recent years, the original rig was in place; in fact the well was more or less of a shrine to the petroleum production pioneers. In June 1953, the petroleum producers set a bronze plaque by the well, worded as follows:

First Commercial Oil Well In California

On this site stands CSO 4 (Pico 4), California's first commercially productive well. It was spudded in early 1876 under the direction of Demetrius G. Scofield, later to become first president of the Standard Oil Company of California, and was completed at a depth of 300 feet on September 26, 1876, for an initial flow of 30 barrels of oil per day.

Later in the same year the well was deepened to 600 feet using what was perhaps the first steam rig employed in oil well drilling in California.[25] Upon this second completion it produced at a rate of 150 barrels a day and is still producing after 77 years.[26]

The success of this well prompted the formation of the Pacific Coast Oil Co. of California and led to the construction of the state's first refinery nearby.[27] It was not only the discovery well of the new field, but was indeed a powerful stimulus to the subsequent development of the California petroleum industry.

Dedicated June 6, 1953, Standard Oil Company of California

Petroleum Production Pioneers, Inc.

Mentryville

At this point it must be said that the Standard Oil Co. has been keeping the gate, at the only entrance to Mentryville, better but incorrectly known as Pico, locked. It is necessary to obtain clearance from the company's Los Angeles Public Relations office to enter the property.[28]

In Pico Canyon stood the big machine shop, built in 1879. In those days machine parts were made on the job. Anything could be made by the old-type machinists, and frequently was. The big lathes were finally bought by our local Al Lowden, and moved to his Newhall Machine Shop. During World War II, they again did their bit.

Close to the machine shop [in Pico] was the loading rack. Heavy iron devices of all shapes, sizes and descriptions flowed over its edges. There were weird fishing tools, developed for the problem of the moment when 500 feet was a deep hole, and 6-inch casing — a big size. There were old spears whose use is forgotten. There were wrenches, painstakingly made for equipment long gone and not regretted. Most of this equipment was shipped East 20-odd years ago and is part of the permanent exhibit of the infancy of the oil industry .

Jack Plant 'Spider'

The old plant at No. 4 had sailed around the Horn from Titusville, but it has been replaced by a modern pump, and the old 40-foot wooden derrick has been taken down.

The cables emanating from the jack plant that pumped the many wells wandered over the hill sides, turning corners with the aid of their butterflies. It didn't seem possible that a sober man could make such a hook-up — maybe they didn't. It isn't humanly possible to find proper words to describe a jack plant hook-up — call it a spider in the center of a huge rambling web, with pumping wells at each web tie-in, and the spider acting as an inhuman power source.

Nothing, now, is of exceptional interest on the other side of the gate but the well sites and the hill slopes.

Back to Pico Canyon

The Pacific Coast Oil Co. intended to develop the prospects at one of its properties in Moody Gulch, up by Santa Cruz, first, but the equipment had not yet come in. Before the end of 1882, Moody Gulch had not only been drilled but finished, as each new well lowered production of the older wells. That brought everything back to Newhall and Pico Canyon.

Among Scofield's friends of Titusville must be included Lyman Stewart. Actually they had been schoolmates in Oil City [Titusville, Penn.]. There was a definite shortage of drilling contractors in the West, and by 1882 oil prices had dropped out of sight. Pico Canyon was practically the only field not overloaded with drillers cutting prices.

In the West, C.E. Youle and an acquaintance of his, named Dull, were the only active experienced contractors. Stewart had known Youle, Scofield, Mentry and Scott when they had an been in Oil City together. Actually, I.E. Blake, of the sarne group, and now of PCO, seems to have been the man who sold Stewart the idea. In the winter of 1882-83, Stewart and his oldest son Will came to Pico Canyon where Blake had offered drilling locations. Stewart sub-leased land and got in touch with his old Pennsylvania partner Wallace Hardison, who picked up a couple of heavy rigs and reached Newhall in 1883.

Between them they had about $70,000 in equipment and $65,000 in cash (according to Taylor & Welty in Black Bonanza). They also had had much experience in the oil fields.

Lyman Stewart

Lyman Stewart was an intensely religious man, sometimes reproving his drillers for profanity. It took no time at all for their sublease in Dewitt Canyon, just east of Pico Canyon, to become known as "Christian Hill." In spite of, and possibly because of this idiosyncrasy, Hardison & Stewart lost their tools at 1,850 feet and no showings. They moved 475 feet easterly and drilled No. 2 to 1,050 feet. There they again lost their tools. Seven hundred feet westerly from No. 1 they found a trace only at 1,650 feet. Number 4 was a duster and was abandoned. So was No. 1.

The next dusted on Smith Farm No 1. At this point they moved up to Santa Paula Creek and made their seventh consecutive duster.

First Bit of Luck

No bank rolls could stand that kind of luck. In real desperation they went again to Blake for a chance on a better location. They got it and brought in Star No. 1 for 75 barrels at 1,650 feet.

To get essential capital, they had to sell Star No. 1 to PCO. They sold their office warehouse which then stood on Main Street.[29] It was later moved to 748 Spruce Street[30] and finally razed in 1952, then moved to Santa Paula, joined up with Thomas Bard (who was settling up the Estate of his uncle, Thomas Scott and the Mission Transfer Co. Museum in Santa Paula), and later formed the Union Oil Co. of today.

The development of the Newhall oil fields continued slowly and consistently. R.W. Walling shows CSO Nos. 5 and 6 on production of 47 and 50 barrels daily, respectively, in 1880; two other wells drilled this year were failures. Mentry completed four wells in 1882, and 12 wells in 1883. Each year the totals grew. One more interesting well was PCO 17, drilled in 1899, as the Western Prospecting Co. of Denver tried to drill this with diamond drill, which method had to be abandoned at 60 feet.

70 Wells by Mentry

Under Alex Mentry, there were apparently 70 wells drilled in total.[31] The transposition or the original drilling names (when the Standard Oil Co. took over the operations) complicates the record somewhat.

In Dewitt Canyon, easterly from Pico Canyon, seven abandonments mark the record prior to 1900. In Towsley Canyon, 18 wells drilled by various companies are recorded by Walling prior to 1932.

Wiley Canyon was part of the Standard Oil properties, on which 30 wells were drilled for very small production. Development started in 1883.

Drilling in Ellsmere [Elsmere] Canyon was started by the Pacific Coast Oil Co. in 1889, and 22 wells were drilled by them.

Starting in 1900, E.A. & D.L. Clampitt drilled nine more wells. In 1920, Republic Petroleum, Ltd., drilled two wells.

Development in Whitney Canyon started in 1894. Various outfits drilled 13 wells to 1934.

Rice Canyon started in 1898. According to the late Will Mayhew, George Carmine and Mayhew opened the road into Rice for the Pacific Coast Oil Co., by order of Alex Mentry.

After the first well came in (3 bbls.), Rice bought 50 acres from Steve Lopez, and Mayhew opened a trail good enough for a buggy to get over to Wiley Canyon.

Mrs. Mayhew opened the cook house in 1899. John Floyd was foreman. An old Indian named Pico had a homestead there which was bought out. Galbraith, Hitchcock and Mayhew built the cook house. Alf Swanson was tool dresser. Clark Filer and John Sanders were drillers.

Rice Canyon Field

Dallas Gallagher drilled the first of nine wells for Rice. One was 1,700 feet deep. It was good but the casing caved in. They lost the hole. Rice's partner, Bradshaw, pulled the 7 5/8-inch casing. Dave Harpster drilled the deep hole. Charles Suraco, Lu Boseren and Mayhew worked on the rig. Rice sent Jim B. Watson, an old diamond driller from the copper mines, in to drill at $10 a day. Allen Craig, Munday and Cooper worked with him. Jack Gelhart, E.A. Johnson and James McHugh drilled the only duster.

Then oil dropped 40 cents a barrel and Rice quit. He died in 1900. He was from Boston.

The first pumper was Frank Stobe. When operations quit, Mrs. Mayhew was pumping for Rice, and Will Mayhew was pumping for Walton Young, now superintendent for Standard,

At the head of Placeritas Canyon, Freeman & Nelson drilled three wells, beginning in 1899. Other companies drilled eight failures.

The Tunnel area was opened in 1900 by E.A. Clampitt. In the next 30 years, 30 wells were drilled, chiefly by the Clampitts, also by the Southern California Drilling Co. and the York-Smullin interests.

A Petroleum Economy

The foregoing data is from Walling, and terminates at 1934. Add to the wells listed, 58 unassorted wildcats for a total of 273 wells in the early days. There was no local industry payroll or economic activity approaching that of petroleum.

Outside of the Newhall Ranch payroll, spread thinly from Newhall to Piru, there were very few agriculturalists or stock men.

California Star Oil Works Co. had but one superintendent during its operating life, Alex Mentry. Pacific Coast Oil Co. the same.

Mentry died in 1900, during the Standard Oil takeover. His place was filled by Walton Young, who remained as superintendent until the early 1930s.

Then Hugh Barton and Charles Sitzman came in and remained until the latter's retirement. The company now has only a caretaker at old Mentryville.[32]

Old-Timers Gone

Apparently, with the exception of Walton Young, practically none of the men who worked with Mentry are now around. Locally, Bert Russell worked with Walton Young.

During the last years of Pico Canyon, maintenance of the five children, necessary minimum to continue the Felton School District, was a real problem. In the early 1920s, school was on the ragged edge of being closed when Maurice Dill came out from Nova Scotia with his family of eight children. Dill did not have to ask Young twice for a job. It was too good to be true. Felton School District could continue.[33]

The Petroleum Jig Saw

Mining was almost non-existent by the time petroleum development started. It was only the payrolls of the old fields that carried Newhall until the middle 1920s. It should be pointed out, however, that from time to time, major projects for the city of Los Angeles were under way, such as power lines, pipelines, aqueduct construction, highways, etc. These provided temporary payrolls.

Actually, it was the completion of the Ridge Route and the Mint Canyon road and the Newhall Tunnel that ended the isolation of the areas. From then, the location of the town governed its destiny and a more normal development began.

No theories about depositions or origins of our local fields are presented here. Years will pass before those will be authoritatively known, for this is a difficult oil field, being shattered, in a geologic sense, into a thousand and one isolated, dovetailed, jig-cut, irregular irregularities. If you disbelieve that last sentence, ask any geologist.

Did The Signal editor mutter, "Those days are gone forever?"

Have you noticed the shrinking of the boundary limits of this story? In the beginning, all the Santa Clara River drainage area in Los Angeles County was included. But parts keep dropping off. Camulos Ranch went with the first change of the county boundaries. Soledad camp flared in the limelight and disappeared, along with most of the canyon territory. Lyon Station fades, vanishes, and Newhall is born in its place. You have read of the development of the old Pico and Newhall oil fields. They were within six or seven miles of the Newhall townsite and started long years ago.

Oil in Newhall

The actual development of interest in oil possibilities right in town, as it were, was a much later development.

In the 'Teens, the 10-day wonder of the petroleum world was the Kettleman Hills oil field. Its discovery was attributed to the genius of W.H. Ochsner, a practicing geologist of the day who made himself quite a reputation. Incidentally, he was also a geologist for the Occidental Petroleum Co., then doing a little wildcatting in the nearby canyons.

In 1924, Healey & Perkins were opening a campsite subdivision in Wildwood canyon [in Newhall]. There was a question whether they might be selling real estate which was potentially oil ground. The late Dr. Norman Bridge recommended Mr. Ochsner as best qualified to conduct an examination. The Ochsner Report of November 1925 recommended the area as worthy of development. Up to that time the only wildcat well was that of the Howard Petroleum Co., which had bottomed and busted under 2,000 feet. The only thing of interest encountered in the operation was a saber-toothed tiger's tooth, found by Henry Wertz, Sr., when digging the cellar for the rig.

In those days all wells had cellars. It was before rotary drills had been developed. The tough blue Fernando clays here encountered sent the crews out after old bottles, tin cans or what have you to aid the drill bit's bite. Water plugged off with "seed bags" — just what the name implies. Derricks were of wood, maybe 60 feet high. (In fact when Mr. I.C. Gordon started as a rig builder in the old Salt Lake field, in Los Angeles, derricks were only 26 feet high.)

Copies of the Ochsner Report were well circulated in oil circles "downtown," and first called attention to "close in" oil possibilities at Newhall. In 1930, a well was started at the south end of Wildwood Canyon by R.E. Kitching. After many vicissitudes, delays and aberrations, which culminated in the well being taken over by the British American Oil Co. in 1940, a lessor-lessee dispute lead to the well's abandonment short of 5,900 feet.

Happy Valley

R.W. Sherman was then geologist for the British American Co. and was intrigued by his studies of the Happy Valley area. The continuance of his interest in the "close in" field has so far influenced the drilling of 14 wells, while cash distributions as lease rentals to local land owners have been estimated at between $1.5 million and $2 million. That particular field is yet to be found, although five of the 14 wells mentioned flowed at one time or another, and three of the wells near San Fernando Road still produce commercially.

1930 is also the starting date of the Newhall Refinery. It is not our oldest local refinery by some 50-plus years. Nor is it our biggest refinery — that is probably the plant of Sun Ray on the Rancho San Francisco lease. It is, however, the plant most important to Newhall, for, especially since W.D. Parks and Ed Ericksen bought control of the plant in 1943, it is a most important local economic factor employing many local people at top wages.

The Cops Well

In 1938, W.J. Clark (whom you previously met in connection with the successful placer mining operations in Bouquet Canyon) organized the Holbrook Petroleum Co., leasing some 4,000 acres of land from The Newhall Land & Farming Co., being the general area between the old airport (on Newhall Avenue north of 16th Street), Highway 99 and Tip's Coffee Shop at Castaic Junction.

Howard A. Broughton was the company geologist. Two wells were drilled. The first (known locally as "The Cops Well," for many of the stockholders were on the Los Angeles City Police force), bottomed at 6,224 feet. The best showings were at 5,700. But the water came in the well didn't "make" and the company tried again. The first well was located not too far from the airport. The second was off Highway 99. It bottomed at 3,800.

The area has since been drilled by various major oil companies, so far without any success, the last well being drilled by the Standard Oil Co. of California about 1950.[34]

The work was of interest as one of the earlier attempts to develop oil close to Newhall.

First Big Field

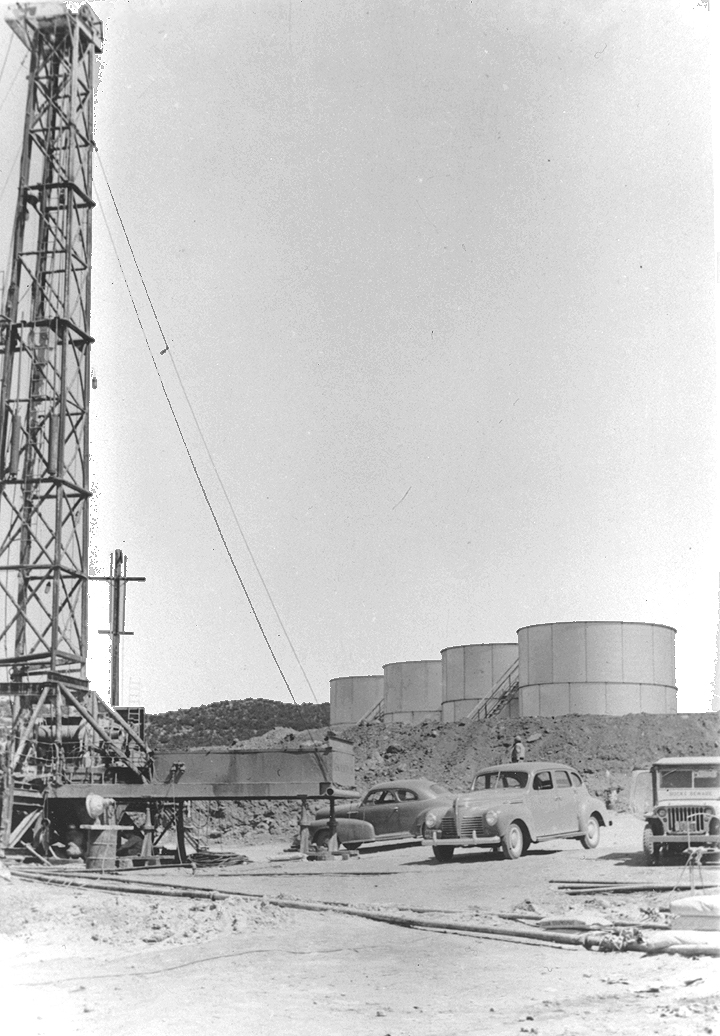

Havenstrite oil rig near Newhall Avenue (formerly San Fernando Road) and Sierra Highway, 1949 | Click image for more viewsThe last of the fields so far mentioned was the Tunnel area which had enjoyed a revival in the late 1920s.

First of the really big fields locally was the Barnsdall Oil Co.'s (now known as Sun Ray [in 1954]) Newhall Potrero, on the Newhall Ranch. It started in 1937 and, incidentally, is generally accredited to the geological perspicuity of R. W. Sherman.

This field today produces about 9,000 barrels of oil daily from some 93 wells [in 1954].

In 1940, R.E. Havenstrite brought in the first of the wells in the Del Valle area, just beyond Castaic Junction, for some 400 barrels. Today that field produces 2,700 barrels daily from some 80 wells [in 1954]. This field is accredited to the geology of R.W. Sherman.

It took 18 years of development failures by various oil companies, including Barnsdall, Texas, Standard, Humble and others before the first barrel of oil came from the Honor Farm [Peter J. Pitchess Detention Center in Castaic] area. About 60 wells produce a short 8,000 barrels of oil daily there today [in 1954].

Madness in Placerita

The "old" Newhall field produces about 440 barrels daily. After 75 years of steady production, that is darned good.

Most readers will recall Placeritas — the Mad Mountain of 1951 — the insanity, the hysteria, the everything of the mad ultimate where two wells were within 58 inches of each other — and 25-foot plots located God alone knew where, without true boundary lines, would be drilled by one for benefit of another — and no philanthropy involved.

Placeritas was first drilled in 1899. Today the field of 1951 is producing about 7,500 barrels of oil daily from 326 earth perforations. It took only a half century of development to find the field.

"To find the field. Aye, that is the question!"

Whether to be lucky and drill right into a nice shallow pocket of clean oil, or whether to search for a lifetime of hardship and disappointment and end up as one probably started — broke.

The source of data for the later days of oil are to be found in Bulletin 118, plus the regular monthly oil and gas production reports, of the Division of Mines.

Standard Oil Sells Direct to Customer

While talking oil, let's glance back a little. Pico Canyon was the only successful commercial oil field in California up to 1885. In 1879, a two-inch pipeline conveying oil to the refinery at Elayon (Railroad Canyon or Pine Street) was laid — the first pipeline for conveying oil.

Up to 1895, Ventura-Pico fields were producing 90 percent of California oil.

"In the Eighties, the Standard Oil Company opened their office in San Francisco," says S.W. Tait in The Wildcatters, "and sent out salesmen on bicycles and distributed kerosene, Eureka harness oil, Mica axle grease, coach oil in light wagons with high buggy wheels."

Isaac Marcosson in Black Golconda points out that "the very great success of Standard Oil was due largely to its inspiration to sell direct to the consumer, and thus opening their own retail establishments. This is generally accepted to be the origin of the thousands upon thousands of service stations which dot the whole United States."

It was in the 1890s that Scofield first contracted with Standard Oil to market all the products of his company. Quite naturally, the stock of the Pacific Coast Oil Co. was acquired by the old Standard Oil Trust in 1900. When the Trust was dissolved in 1911, Standard Oil Co. of California succeeded to ownership of California properties and business. D.G. Scofield became president and held that office until his death in 1917.

Patience Necessary — and Luck

When one talks oil, a sort of glow pervades the conversation as a "getting rich quick" state of mind develops. It takes more patience — and luck — to get rich from oil development than almost any other field of endeavor. Take a local case history.

On this ranch, the first oil lease was written in 1921, when the Howard Petroleum Co. started a well which finally reached a depth of 700 feet and the company busted. Except for occasional short-time leases to Victor York and others, the ground was quiet, petroleumistically speaking, until 1930, when Roy Kitching promoted his Superba Well. That dragged on, not down, for more than a decade until the well was taken over by the British American Oil Co., re-named the Edwina Well, drilled just short of 6,200 feet and abandoned as the result of a lessee-lessor imbroglio which included the filling of the drilled well with pipe tools, concrete landed on top of the drill, then in the throes of a fishing job.

Operations in Wildwood

Airline Oil Co. drilled the area in 1942 to 4,963 feet. The well flowed but was abandoned. Next, in 1946, came the "Tomato Can." After several days of spasmodic but abortive attempts at a flow, the well was abandoned. In 1949 came the Rothschild Well, bottomed at 4,963, which did flow for awhile but was ultimately abandoned.

In 1953, the R.E. Bering Associates drilled again to 4,163, where hope on that hole vanished.

The ranch permanently abandoned? Don't be silly. The rigs will yet be back. In fact there is a location cut and not yet drilled that will bring someone in. For that story of attempt and failure is the story of all of our producing fields. It is a reasonable parallel of the development story of the Needham Estate, the Clampitt Leases, the Castaic Hills. From the land owners' point of view, as a means of getting rich, some less promising but steadier income — such as a small pay check — might get faster results.

Boom and Bust

There is yet another type of oil development: the Boom. Newhall has had that, too. How long ago? 1949 — and those that went through that town lot leasing period won't forget the raving insanity that prevailed for a few days. Within five days, 25-foot townsite lots hit a lease bonus price of $200. Isolated maniacs paid from $10,000 to $15,000 for an acre's worth of town lots, contiguous. Most of those spectatcular offers ended as offers. Owners would not lease or sell. In short, two fools met.

It all started when Dick Sherman's location on Hill Street blew in for 500 barrels — and it did blow in — and kept flowing into the tanks until a pumper got too enthusiastic on the load, wanting to get out quick to make a party, according to the story. Water and oil wells aren't "'made" when you find the fluid. Lots of things can yet happen, and too frequently do, with an end result of another "lost hole."

Signal Tells Story

The best tabloid description of that particular moon madness is given by merely swiping the headlines and data lines of The Signal. In a nutshell, you have the story. See The Signal headlines:

- Nov. 18, 1948 — SHERMAN WELL IN FOR 500 BARRELS. Major pool discovery believed uncovered by wildcat on Hill Street.

- Nov. 25 — WILD LEASE SCRAMBLE AS SHERMAN WELL TESTS BIG OIL AND GAS PRODUCTION.

- Dec. 2 — LEASE SHARPERS SCRAM AS SALT WATER INVADES SHERMAN DISCOVERY WELL.

- Jan. 6, 1949 — DRILLERS RACE TO PIERCE OIL DOME. MORE RIGS TO BE ERECTED NEXT WEEK.

- Jan. 13 — COASTAL DRILLING ON LEGION PROPERTY ARCADIA & PICO ROAD DOWN AROUND 3,000. EAGLE-CHAPPEL FINISHING AT lOO. MILLER LOCKHART BELOW 2,000. SHERMAN BOWMAN 8OO-FOOT WATER STRING SET. FAIRFIELD (north of Chappel on Arcadia) RIGGING. R.W. SHERMAN GETS OIL LEASE AT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL. 11 ACRES AT $2,000 AN ACRE. 28 PRODUCTION WELLS IN PLACERITAS.

- January 20 — OIL TENSION AT PEAK AS EAGLE-BISHOP WELL HEARS OF OIL STRUCTURES.

- January 27 — WORD AWAITED ON EAGLE CORES AS FIVE WELLS DRILL AHEAD. TANK FARM HINTED.

- February 10 — EAGLE NO. 1 MISSES TEST.

- February 17 — ARCADIA RIGS QUIT. HAPPY VALLEY TO BE TRIED. PLACERITAS FIELD SPREADS.

- March 17 — ALL DRILLING ON NEWHALL TOWNSITE LEASES SUSPENDED.

And that is that. Yes, they'll undoubtedly be back someday, not too far from the same locations, the same hopes rampant.

There will be new faces but old ideas.

Decidedly, it is far too early for anyone to deny that Newhall is an oil town.

©1954/1975, SANTA CLARITA VALLEY HISTORICAL SOCIETY • RIGHTS RESERVED.

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.