|

|

The Golden Spike: The Chinese Contribution.

By EMMA LOUIE.

From the Golden Spike Centennial Souvenir Program

Sept. 5, 1976.

[Centennial Index][Story of the Golden Spike][The Chinese Contribution]

The Golden Spike: The Chinese Contribution

As researched by Emma Louie of the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California.It was the Chinese who made possible the transcontinental railway, and then, seven years later, the joining of Los Angeles to that railway, the event celebrated at Lang.

Charles Crocker, in charge of construction for the Central Pacific, found that the people of many lands who came to the West were generally looking for gold or land, not for back-breaking work. How would he made a roadbed across desert and mountain?

He found his answer in the diligent Chinese, who would work until they dropped. With that work force the Atlantic and Pacific were linked. Crocker then became president of the Southern Pacific Railroad, and promptly hired over 3,000 Chinese, assigning 2,000 to the grades and tunnels of the Tehachapi mountains and another 1,000 to digging the San Fernando tunnel.

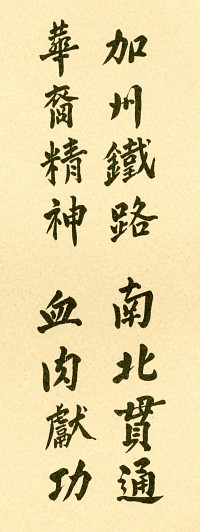

"On this Centennial we honor over three thousand Chinese who helped build the Southern Pacific Railroad and the San Fernando Tunnel. Their labor gave California the first North-South Railway, changing the State's history."

Crossing the barrier of the Tehachapis between Bakersfield and Mojave proved to be as challenging and formidable a task as that of the Sierra crossing. Wrote historian Remi Nadeau, "Working with horse-drawn plows and scrapers, the Chinese legions carved cuts as deep as ninety feet across the rugged crags." The railroad zigzagged its way up the slopes through seventeen tunnels. Due to the brittle granite, cave-ins occurred regularly. Nadeau mentions the loss of over a dozen Chinese lives due to accidents and other mishaps.

One thousand Chinese and five hundred whites worked on the San Fernando Tunnel section of the railroad. The work force faced enormous difficulties as "seven thousand feet of water-ridden trap and sandstone formation lay ahead of the Southern Pacific tunnel diggers." The mountain was saturated with oil and water; its soft blue rock formation caused frequent cave-ins. Due to such accidents, so common to this work, some lives were lost.

Deep in the mountain, hundreds of feet below its surface, oppressive heat and dampness made the work unbearable. "Oriental toilers fell at their work in regular succession and had to be carried to the sunshine burning with fever."

In July 1876 the Chinese tunnel diggers broke through the final partition of earth. It had taken more than a year to complete the longest tunnel west of the Appalachians. As a great engineering feat, the San Fernando Tunnel still stands as a tribute to its builders.

The long-awaited railroad was finally to be connected in a "last spike" ceremony. Unlike the golden spike ceremony that joined the first transcontinental railroad, where no Chinese were present, thousands of Chinese were on hand at Lang Station to witness the event. Nadeau tells us that the Chinese "...clad in basket hats, blue denim jackets and trousers, and cotton sandals, stood along either side of the mounded right-of-way. Four thousand strong, they lined the roadbed in military file, leaning on their long-handled shovels, 'like an army at rest after a well-fought battle.'" Along with other workers, they watched city dignitaries from Los Angeles and San Francisco gather for the ceremony, and joined the cheering and shouting when the gold spike was driven in.

Following completion of the railroad the Chinese settled in many towns along its route. Prior to its construction, few Chinese lived in southern California. The population of Los Angeles's Chinatown tripled despite the fact that it was the scene of the infamous 1871 Chinese massacre. Many Chinese also settled in places such as Bakersfield, Hanford and Visalia. Railroad building also took them to other western states where many eventually settled.

Railroad construction was not the only occupation in which the Chinese were found. The early immigrants on the West Coast were merchants and traders. The influx of Chinese immigrants began after the news of the California gold strike reached Canton, China. Thousands began coming to "Gum Shan" or the "Golden Hills," their name for California. Political chaos, economic instability, natural disasters in China all combined to induce the Chinese to leave. The overwhelming majority of immigrants to this country were the Cantonese-speaking people from the southern province of Kwangtung.

Not long after their arrival, the Chinese found their way into other work, particularly in the service occupations, such as operators of laundries and restaurants and as domestic workers. The Chinese pioneered the abalone industry; by the 1870s Chinese abalone junks were a familiar sight in San Diego. They were active in the light industries such as cigar making, shoe and boot manufacturing, the sewing trade, etc. Not surprisingly, they were in the agricultural business, older Californians today remember, such as running truck farms. The Chinese vegetable peddler was depended on by housewives in every city. Before the close of the 19th Century, the Chinese were an important part of the economy of the West.

Few educated Chinese emigrated in those early decades. The Chinese immigrants were not in the professional field; it would take the next generation of English-speaking Chinese Americans to fulfill this role. But the appearance of an American-born second generation was delayed for several reasons.

In accordance with their own customs, Chinese immigrants had left their families behind. Few Chinese families existed in America prior to the 1880s when the Chinese Exclusion laws went into effect. From the 1850s on, beginning with the Foreign Miner's Tax in 1852, numerous California state laws and city ordinances were enacted against them. When mining and railroad building took them to other western states, anti-Chinese laws were also passed. As the railroads brought Americans West to settle, many Chinese went east to escape the hostile climate.

From the mid-1870s into the 1880s, the anti-Chinese movement in the West grew more violent, as they appeared to the Caucasians as economic rivals. With labor and politicians clamoring for action, Congress took steps on the issue of Chinese immigration. Beginning in 1882 a series of Chinese Exclusion laws were enacted to forbid further immigration of Chinese laborers.

The exclusion laws had a widespread and dire effect on the resident Chinese. Their numbers sharply declined from 132,000 persons in 1882 to the lowest point of fewer than 62,000 in 1920 as deaths and departures were not replaced. The ensuing years saw the decline of Chinese in their diverse occupations; discrimination kept them from other jobs as well. The Chinatowns in large cities across the nation became ghettoes of haven and protection. Few foreign-born wives were permitted to join their husbands in this country. There was one bright note in these dismal years: a small and slowly emerging second generation.

The 1943 Congress repealed the exclusion laws. From then on various laws enabled the Chinese to be reunited with their families or find political refuge here. The new immigration act gave opportunity to other Chinese residing in various countries to emigrate here. Today's Chinese-American population is no longer confined to the Cantonese-speaking, but includes Chinese from different regions, so that many dialects and customs are represented.

The Lang celebration has special meaning for us of Chinese descent. We have the opportunity to recognize, not only that Chinese labor helped to build the Southern Pacific, but also to realize the importance of this railroad to the economic development of Southern California. We also have the opportunity to recognize the significant role of Chinese labor in the developing West.

Today's Chinese Americans work in many occupations and professions. From the Chinatowns in large cities and small towns where Chinese storekeepers and laborers had settled, their sons and daughters have gone forth as teachers, doctors, engineers, lawyers, mechanics, clerks, etc. Americans of Chinese descent have been elected as state officials, city councilmen and appointed as judges. Where once their grandfathers lived on the fringe of American society, Chinese Americans can participate fully in American life.

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.