"Newsmaker of the Week" is presented by the SCV Press Club and Comcast, and hosted by Signal City Editor Leon Worden. The program premieres every Wednesday at 9:30 p.m. on SCVTV Channel 20, repeating Sundays at 8:30 a.m.

"Newsmaker of the Week" is presented by the SCV Press Club and Comcast, and hosted by Signal City Editor Leon Worden. The program premieres every Wednesday at 9:30 p.m. on SCVTV Channel 20, repeating Sundays at 8:30 a.m.

This week's newsmaker is Brig. Gen. Janis Karpinski, former commander of the U.S. Army's 800th Military Police Brigade in Iraq. The following interview (rt: 2:10) was conducted by telephone on Tuesday, June 29, 2004.

SCVTV: Gen. Karpinski, thank you very much for joining us today.

Karpinski: My pleasure. Thank you for your interest.

SCVTV: Please give us a thumbnail sketch of your background. You live in South Carolina now; where did you grow up?

Karpinski: I grew up and I lived most of my life in New Jersey. My sisters and my brothers all still live in New Jersey, so I'm up there quite a bit. Went to school in New Jersey.

SCVTV: Did you go to college before joining the Army?

Karpinski: Yes I did. I studied English and secondary education.

SCVTV: Did you ever teach high school?

Karpinski: I did, as a long-term permanent substitute for about a year and a half.

SCVTV: And then — you up and decided to join the Army?

Karpinski: No, it wasn't a spur-of-the-moment thing. I'd really been interested in the military since I was about five years old. My best recollection of that — I didn't grow up in a military family or anything, but my best recollection of that is, I saw some photographs that my mother had in a box in what we called the "cedar closet," and I was going through that box when I was really young, and I saw a picture of my father with his uniform on. And I thought, gee, this is so neat, and I talked to him about it. And in that same box was his hat, one of his hats that he had worn, and I put that thing on my head, and my mother said that I would wear it around the house as often I could get away with it.

SCVTV: At the risk of dating you, who was president when you signed up?

Karpinski: When I signed up? Gee, that's something I should know right away, right? I think it was probably Nixon.

SCVTV: Did you come from a Republican or Democratic household?

Karpinski: My mother was, as far as she was concerned — she was part of the Republican Committee in New Jersey, and then she was a committeewoman for Union County in New Jersey. My grandfather was part of the Republican Committee for the state of New Jersey and went to all of the Republican national conventions. My mother believed that there was one party, and I grew up in that kind of environment.

SCVTV: You're Army Reserve now, but you signed up with the regular Army?

Karpinski: Yes, I did.

SCVTV: How long did you serve?

Karpinski: Just short of 10 years. It was something that I — like I said, I was very interested in being in the military, and then managed to do that when I realized I probably did not want to teach school at that particular point in my life. And everything fell into place. The recruiter stopped by; I talked about going to jump (airborne) school, and he said I could probably do that; the only limitation was that I was a female — and that wasn't about to change. But we worked through that, too, and I went off to basic training down at Ft. McClellan, Ala.

At that time they still had the Women's Army Corps, but they cased the colors and they closed that program. They retired the Women's Army Corps while I was actually going through training at Ft. McClellan. And then we went into full integration — it was supposed to be a seamless integration — to mainstream us into the different branches that were open to women at the time. And we were not always welcome with open arms by any of those organizations.

SCVTV: Was it kind of a boys' club?

Karpinski: Oh, absolutely. We were intruders. And my first company commander — I was a lieutenant, had just come from jump school and arrived at Ft. Bragg, and my first company commander told me that he didn't agree with women being in the military police. He didn't agree with women being in any of the branches. "Go back to being WACs." And actually he was married to a woman who wanted to be a mother and be a wife, and that's the position he thought all women should be in.

SCVTV: Why did you ultimately leave the Army?

Karpinski: Why did I opt to leave the army?

SCVTV: Yes, after 10 years.

Karpinski: Well, it was just short of 10 years, and I kind of put that mark on the wall — that if I didn't feel like there (were) going to be opportunities, and the outside world was more interesting or presented more opportunities, then I was going to do that. So I did.

SCVTV: As a civilian, what do you do for a living?

Karpinski: Well, I was doing a lot of training in different corporations and doing corporate improvement programs. I don't mean to say that I got into it by default — but when I was living in Atlanta, I was doing, on a voluntary basis, I was doing Volunteers in Literacy, and I had the opportunity to teach some — provide reading lessons to some pretty powerful people. And then I left and went over to the Middle East during Desert Storm because I was a reservist at the time.

SCVTV: What did you do in 1991 Desert Storm?

Karpinski: Well, I was assigned to 3rd United States Army; the headquarters was at Ft. McPherson, Ga. And they deployed — the concept that 3rd Army applies is — and it really does work — they have active components, they have reserve components, and they have a civilian work force, and everybody works together. When you have a uniform on, there is no distinction between whether you are a reservist or whether you are active component because you have a job to do and you make a contribution. So they deployed an early entry cell. I was a targeting officer for 3rd Army. And Gen. Schwarzkopf wanted the targeteers there as early as possible, so we deployed very, very early on, after the Iraqis crossed the border and invaded Kuwait.

SCVTV: In addition to an operational background, don't you have some kind of background in military intelligence?

Karpinski: I do, but it's really from a different perspective. As a targeting officer, I looked at the types of targets; we prepared what they called target folders — it talked about the construction materials; it talked about the value of hitting that particular target; that kind of thing.

And my other experience with intelligence was at the tactical level, because I had a tour with special operations, so I had to develop the intel for the locations that they were going to.

SCVTV: Fast-forwarding, how did you become commander of the 800th Military Police Brigade? Basically, you were America's chief jailer in Iraq, right?

Karpinski: I was. Yes. I was.

SCVTV: Is that something you asked to do? You wanted to be a prison warden?

Karpinski: No. As a matter of fact, I was over in the Middle East — following Desert Storm, I stayed as an adviser in the United Arab Emirates, for developing women's military training programs. I stayed there for almost six years and learned a tremendous amount about Islam and about the Arab mentality, and about how their culture is. I have tremendous respect for them.

Then I was getting ready to come back to the United States and I got a packet to put in for command opportunities as a battalion commander. So I applied for command of a military police battalion and was selected, and my battalion was in Tallahassee, Fla. And it was an EPW, an Enemy Prisoner of War, battalion. So I spent my time as a battalion commander doing EPW-type of training. And then I left there and went into really operational assignments, generic kind of assignments, chief of staff, branch and material, as they call them.

So when I was eligible for general officer, my battalion, even as a reserve battalion, was subordinate to the 800th Military Police Brigade. The commander at the time asked me, what did I see in the future? What did I want to do? And I said, "I really love operations, and then eventually I'd like to take your job." So he said, "Well, this is the best MP assignment in the reserve component." So that was my first choice.

You have to — the process for applying for different positions as a general officer is a little bit complicated and it's not really that important, but that was my first choice. So I was actually very pleased when I came out on the general officers list and I was selected for command of the 800th Military Police Brigade. It was a privilege and I was just absolutely thrilled with that opportunity.

SCVTV: What was you military rank at that time?

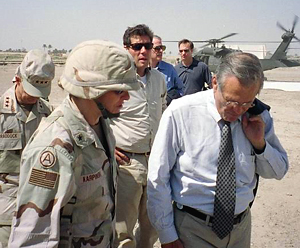

Brig. Gen. Janis Karpinski and Capt.

Vance Kuhner in Iraq. Photo courtesy of Brig. Gen. Janis Karpinski

|

|

Karpinski: I was a colonel. I was an 0-6, and I was the chief of staff to the largest reserve command in the United States. So I was selected and I knew that they were already deployed, and did as much homework as I could on the status of the units and how many people they had cross-leveled and their numbers and everything. It was not a good picture, actually, but I wanted to go and serve with my soldiers in a combat zone. I really wanted to do that.

SCVTV: So when you took over, many of your soldiers were already deployed in Iraq?

Karpinski: Yes. The units had already been deployed for six months, seven months, by the time I got there.

SCVTV: You got there when?

Karpinski: Middle of June of 2003, and I took command on the 29th of June.

SCVTV: So you didn't see action during the "major hostilities" of the months before.

Karpinski: No, no. Because the 800th MP Brigade and subordinate units were primarily located in the south of Iraq. They were located very close to the border with the largest EPW camp — that was Camp Bucca — and they were at two other locations just north of that location.

SCVTV: So in late June, you're in charge of how many prison facilities?

Karpinski: Well, at that particular time we had an EPW camp, a large one, where they had held about 8,000 prisoners total, and the majority of them had been released. And then there were three other facilities. But we were taking control of 16 prisons and correctional facilities located throughout Iraq.

SCVTV: Were all 16 in use in June?

Karpinski: No, they were not. As a matter of fact, most of them were not. They'd been so heavily looted, there were practically — in all of the facilities there were no doors, there was no infrastructure. When Saddam opened the doors to all of the prisons in November of 2002 and released all the prisoners, it didn't take long for all of the locals to come and take everything of any kind of value — to include, in one large facility, they came and took sections of the wall away.

SCVTV: The major looting throughout Iraq had just happened before you got there, right?

Karpinski: Yes, it did. But not only that, but, I mean — they would go into, like, the electrical lines. Say you have a conduit with all of the electrical lines and the cables. Well, they would go in and they would loot the copper wires. So it rendered all of that functional conduit useless. It was — we went in and there were, like I said, no doors — everything of any kind of value was completely taken away.

The first time I got to Abu Ghraib, which was the first week of July, I was literally — I was walking with the company commander — who was an outstanding company commander; he was a National Guardsman out of Nevada; Capt. Armstrong, his name was — and he walked the grounds with me of Abu Ghraib, and it was unbelievable. We were actually wading in nearly knee-deep concrete, rebar, glass, everything that was a result of the heavy looting out at Abu Ghraib.

I said to him at one point, "Do you think you can do anything out here?" And he said, "Yes, ma'am, now that you're here, we'll be able to function." And I said, "What do you mean? Who has been taking care of you?" He said, "Well, nobody's been taking care of us." They were assigned to a different headquarters at that time — an active-duty military police brigade — and they never even bothered to go out and check on that unit.

SCVTV: When you arrived, there were 8,000 prisoners in this one detention center?

Karpinski: There had been up to 8,000, but the vast majority of them had been released. There (were) about 3,500 remaining at that time.

SCVTV: How many troops were under your command?

Karpinski: I had 3,400 soldiers assigned to the 800th MP Brigade.

SCVTV: So when you got there, the prisoner ratio was about 1-1, but then — what? They started arresting a lot of people?

Karpinski: There was a complete change. Our mission down at the one prison facility was specifically EPW, Enemy Prisoners of War, because they policed up during the conflict.

SCVTV: Which facility was that?

Karpinski: That was at Camp Bucca, which was down near the Kuwaiti border. That was the function that the brigade had been deployed to handle. That was their mission. So when the vast majority of those prisoners were released after the end of hostilities, the CJTF-7 (Coalition Joint Task Force-7) — the headquarters up in Baghdad — that was (Lt. Gen. Ricardo) Sanchez's command — at that time it was (Lt.) Gen. (William) Wallace; Gen. Wallace left and Gen. Sanchez came in and replaced him. He requested the 800th MP Brigade to come north to Baghdad to take on this prisons mission, and they kept us. By design. The CFLCC (Coalition Forces Land Component Command) commander, Lt. Gen. (David D.) McKiernan, insisted that we remain assigned to CFLCC, because he was concerned that the CJTF-7 headquarters was going to break us up and use us in lots of different military police functions.

So even though — and I went and spoke to a general who was the theater support command commander down in Kuwait — I went and spoke to him twice about my concerns about taking this new mission, when we were not equipped, nor were we of the strength, personnel-wise, to take on this new mission. And he said to me both times, as I was leaving the meeting, "We understand that this is not your usual mission. But you're the best that we have. And that is why you are going up there to do this."

SCVTV: What did you understand the mission to be?

Karpinski: Well, it was no longer involving EPWs, because major hostilities were finished. This was not only to detain Iraqi criminals — regular criminals — as we came to call them, Iraqi-on-Iraqi crimes — it wasn't only to detain them, but it was to restore and rebuild all of the prison facilities so we could house this criminal element.

SCVTV: Was Abu Ghraib in use as a detention facility when you arrived?

Karpinski: No, it was not. There was about — I have to say, correctly — that there (were) about 25 criminals being held there. But they were being held in a very, very austere, triple-strength, concertina-wire-type of a thing, only because they had been policed up in that particular area and dropped off at that prison facility, and we had an MP company there, so they were holding them. But that was it. There (were) only about 25. But that prison, 260 acres, was not ready to hold any prisoners at that time.

SCVTV: Because of the conditions from the looting?

Karpinski: Absolutely. Absolutely. The only advantage was, No. 1, the size; and previously it had been every level, from minimum security all the way to maximum security, and of course the death chamber was there. But it had a 20-foot wall, pretty much intact, all around the whole compound. So we had the ability — or, the contractors were going to start form scratch.

SCVTV: Speaking recently to Torin Nelson, one of the interrogators at Abu Ghraib last fall, he felt Abu Ghraib wasn't appropriate for use as a detention center because of its proximity to town and because it generally wasn't secure. How do you see that?

Karpinski: I agree with him completely. We went and made that argument to (Maj.) Gen. (Walter) Wodjakowski, the deputy commander of CJTF-7. We made that argument to Gen. Sanchez. We made that argument to the ambassador (Paul Bremer).

SCVTV: Before opening the facility?

Karpinski: The facility was in the middle of a combat zone. A hostile fire zone. It was being mortared almost every single night. An MP brigade — in this particular case, a battalion and a company — they are not equipped with the personnel, and they are not equipped with the combat platforms to provide the kind of response to that kind of shelling and attack. Nobody helped us. Nobody wanted to hear our problems. They didn't care. They wanted Abu Ghraib because it was convenient for the division commanders. When they policed up criminals, they wanted the division commanders to be able to drop them off at a central location.

It makes no sense whatsoever, none whatsoever, to operate a detention facility in the middle of a neighborhood where the criminals were the ones throwing the mortars in at you, two weeks before you policed them up.

SCVTV: What alternative did you propose?

Karpinski: Well, we were working very closely with the prisons department in the Coalition Provisional Authority, the CPA, because detention operations for Iraqi criminals was their responsibility. But until they could get enough personal in, civilian contractors, to take on those responsibilities, the military police assigned to me were the ones that were doing their job. So in conjunction with them, we briefed Ambassador Bremer many times. We briefed Gen. Sanchez many times. I routinely went to Gen. Wodjakowski with my concerns, and his usual response to me was, "Figure it out, Janis."

They were still running combat operations in response to the increasing insurgencies. And detention, like usual, is not a priority for anybody. So as a result, when the first mortars managed to come over the wall — and it killed six prisoners and injured more than 40 — I explained to the deputy commander, Gen. Wodjakowski, that this was typical now. The mortars were coming over; they were getting to be better shots; and (it) was placing the prisoners and the military police personnel in harm's way. To say nothing of the medevac operations — that was a textbook operation; there were nine medevac flights conducted that night — and every one of those crews were put at great risk because nobody really knew if the area was cleared or not.

SCVTV: And then the United Nations headquarters were bombed Aug. 19 and the top U.N. official was killed.

Karpinski: Right, Mr. (Sergio Vieira) de Mello. He was a friend and he was a champion of our cause. He understood. And the reason he understood was because he had been out to Abu Ghraib a half a dozen times with me, and he understood the circumstances we were facing out there.

And I can't say that for Gen. Sanchez, and I certainly can't say that for Gen. Wodjakowski. They never bothered to come out there and see what we were facing.

SCVTV: How did the bombing of the U.N. change things in terms of detention operations? How was the climate evolving?

Karpinski: Well, the climate — when they hit the U.N. headquarters — the headquarters was downtown, just outside the Green Zone — they specifically requested that they not have a military presence, force protection platforms, around their building, because they were not a combatant and they didn't want to give the impression — apparently they don't in any location where they set up.

So when that building was hit, in a relatively protected zone — even though they didn't have force protection platforms, like I said, right on site — we knew that we were more vulnerable than we had even imagined. It forced the military police battalion and the companies that were operating out there to be extra vigilant. It forced the issue of getting a combat unit out there to be our force protection. It was promised countless times, but we never received them. And we took measures ourselves, to the extent that we could, to reinforce our entry control points, to get appropriate weapons to the extent we were able in the towers, to get sandbags around the tents for the prisoners so at least they would have a chance of defending themselves if anything happened again. And mortars came in every night.

SCVTV: How was the prisoner population changing? Were there more dangerous people? Were there more numbers of people?

Karpinski: At that time, in mid-August, no. What we were planning to do, and what was working out at Abu Ghraib at that time was, we had a very good contractor working out there, an Iraqi man with his team, and he was restoring the cells. And as indoor cell capacity became available, we transferred our criminals from outside, under tents in an EPW kind of template — you know, concertina wire and tents — we were transferring them out of those facilities in the hard site. And we were down to less than 150. And we projected that they would be out of the wire within a week.

And then Gen. Wodjakowski told me — I briefed that one night, and he said, "Don't close the camp." The name of the camp was Ganci. We had another one that was originally designed for an overflow, but we really didn't need to use it to any extent. He said, "Don't close Vigilant and don't close Ganci." I said, "Sir, we're about finished." He said "No, we're doing these raids, and we're going to put them into your compound."

SCVTV: Meanwhile, at some point here, you became a brigadier general.

Karpinski: Right.

SCVTV: When was that?

Karpinski: Well, in the military, if you are assigned to a position, especially a command position, and you are promotable, which I was, you are frocked. They give you the rank, and people can use that title. So on the day before I took command of the military police brigade, I was frocked. So I was Brigadier General Janis Karpinski. But I was not officially promoted or paid until the 7th of November.

SCVTV: And that requires Senate confirmation, right?

Karpinski: Nope. Senate confirmation comes before you can even be frocked. My Senate confirmation was complete before I even deployed.

SCVTV: So is it fair, then, to say that a year ago June, or May, both the Army and the Senate had confidence in your abilities to lead?

Karpinski: Absolutely. And not only that, but my confirmation was pretty seamless, because I knew that my record was straight. I knew that there wasn't anything in my record that would make them question my ability to take this position. And my confirmation came through very smoothly. So I was confirmed, and I knew that when my promotion date came up, I would be promoted. Because the confirmation is the thing that people sometimes hold their breath about, and it can delay a promotion for several years, in some cases.

SCVTV: A year later, there has been an investigation. Maj. Gen. Antonio Taguba has questioned your ability to command. What happened in the last year?

Karpinski: Well, I don't know. Because I never received an explanation from the people who would have known. My — it was a dysfunctional line of command. We remained, the 800th MP Brigade, me included, remained assigned to CFLCC, the Coalition Forces Land Component Command. We were working in Iraq, and Iraq was the territory of the CJTF-7, or Gen. Sanchez's command. But we were not — we were attached to them, we were never assigned to the CJTF-7.

So, Gen. Sanchez never once — not once did he ever mention to me his concerns about my leadership ability. He never mentored me, he never suggested that I try something differently, he never criticized me, not once. Gen. Wodjakowski, the deputy, who I briefed every other night, never mentioned any concerns. As a matter of fact, he complimented our efforts a lot of times. He said to me at one point, "You're traveling on the road an awful lot." I said, "I have facilities all over Iraq, sir," and he turned around and he said, "Well, be careful out there. It's dangerous."

SCVTV: In layman's terms, when you say you were attached to Sanchez's —

Karpinski: Headquarters.

SCVTV: Headquarters. Sanchez was not your boss. You're not in the same chain of command?

Karpinski: Right. That's correct. But he owned that theater. He owned Iraq. So he was not my boss, but I answered to him. When he had questions about detention operations or jail operations, he asked me. In fact, the first time I met him I was with my predecessor, Brig. Gen. Paul Hill, and Gen. Sanchez specifically said that he wanted to know who the senior military police officer was in his theater so he would have one person to go to if there was ever a mistaken release, or a mistake made by anybody in the military police field. He wanted to go to one person, and who was the senior person? And my predecessor, Gen. Hill, said, "That would be Gen. Karpinski."

But then we very quickly explained to him that we had completely separate functional areas. There were three MP brigades, and never the three shall meet, so to speak. One was assigned to CJTF-7; it was an active component brigade; they were responsible for law enforcement in Baghdad and for training the Iraqi police officers. One brigade was down in Kuwait; they were responsibile for escorting the convoys north to Iraq. And the 800th MP Brigade, my brigade — we were responsible for the entire theater, the entire country of Iraq, and 17 different prison facilities.

SCVTV: How many prisoners?

Karpinski: When we were getting ready to leave, we were compiling statistics. And our population at that time was about 14,000 of security detainees, and then a separate group of 3,800 that we were securing, and then the rest of them were Iraqi criminals.

SCVTV: How successful were you in adding troops to your command of 3,400 people?

Karpinski: There was no process in place to do that. We had no replacement system. And I voiced that concern not only to Gen. Wodjakowski and to Ambassador Bremer, but the person who was able to make that happen, or should have been able to make that happen, was Brig. Gen. (Michael J.) Diamond, who was down in Kuwait. And he said to me, "There is no replacement system. So when you send somebody home, if they're broken or sick or there's an emergency, you don't get a replacement." And I said to him, "Gen. Diamond, I can't manage this way." And he said, "I know, I know. I don't know what to tell you."

You know, my personnel strength was dropping. When my units were getting ready to rotate home, I might be sending a company of 180 home, and I was replacing them with a company of 110. Or fewer. And nobody would help us. The prisons department in the CPA, in the Coalition Provisional Authority, was supposed to be taking over the role of running the Iraqi prisons and jails. And they did not.

They had three people that they hired, they did a straw man, as they called it, they did a proposal, requiring 83 people. It was approved by the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C. And they received funds. But by the beginning of December of 2003, they had three individuals. (...) arrived on the 10th of December, and then the first three went home on holiday leave.

SCVTV: In late August and early September, a couple of weeks after the U.N. bombing, you got a visit from Maj. Gen. Geoffrey D. Miller, the commander at Guantanamo Bay. What was that about?

Karpinski: Well, Gen. Miller was one of several visitors that we got that came for a review of our operations. But as it worked out, Gen. Miller came to visit the military intelligence officer of the headquarters; that was Brig. Gen. (Barbara) Fast. And he was there to help them enhance and improve their interrogation operations.

The reason we were included at any point in his visit was because he wanted to visit several of my prison facilities. So as a professional courtesy he included us on the in-brief, and then he briefed me before he briefed Gen. Sanchez on what his plan was.

Maj. Gen. Geoffrey D. Miller is sworn in before

the Senate Armed Services Committee in May. BG Karpinski said Miller was sent from Guantanamo Bay to Iraq to set up a Gitmo-style prison interrogation system there. AP Photo

|

|

SCVTV: What was his plan?

Karpinski: Well, during the in-brief, he made reference several times to his plans to "Gitmo-ize" the interrogation operations. And he was the commander down at Guantanamo Bay; he was extremely successful, apparently, in getting actionable intelligence from the interrogations that were being conducted there. And he was going to use that template of operations in Iraq.

So, I was concerned, and like I said I was really a guest at the in-brief, but I had to talk. I had to speak up. Because, I said to him, "Sir, excuse me," I said, "I'm Janis Karpinski, I'm the commander of the 800th MP Brigade, but the situation in our facilities is a little bit different that your situation down in Guantanamo Bay. Some of our locations are being fired on at night. We don't even have funding enough to buy a jumpsuit for every one of our detainees. We have thousands of prisoners and not nearly enough MPs to guard them." And he was looking at me like I was some kind of a brainless idiot or something. He was waving his hands at me almost as if he was dismissing me. And he said, "Those things are not a problem. My annual budget is $125 million, and I'm going to give the military intelligence people whatever funds they need. We're going to take care of all that. But first we have to find a location. And we have reduced the list to three or four, and we're going to be out there visiting them." And — obviously I didn't have a voice with him. Because what I was telling him was inconsequential to his plan to "Gitmo-ize" the interrogation operation.

SCVTV: Was Abu Ghraib the only place where interrogations were happening?

Karpinski: Under my control, yes. We had interrogations of a much different nature down at Camp Bucca, when the prisoners of war were being housed there, and then we had a very limited — we didn't, but the military intelligence people had — a very limited interrogation cell at our HVD facility, which was the High-Value Detainees. It was a much smaller operation. That was what people referred to as the "deck of cards."

SCVTV: Describe, if you would, the responsibility of military police in the interrogation process?

Karpinski: Well, up to the point of Gen. Miller's visit, the military police role in supporting interrogation operations was extremely limited, extremely conservative, and by the book. They were detaining — we were responsible for detention operations and all of the things implied. Feeding them, getting them medical attention, getting them showers, those kinds of things. Military police personnel would take the prisoner out of the cell, turn them over to the interrogation team; they would sometimes escort them to where the interrogation was going to be conducted — usually a small room or something — but they were not involved in the interrogation. They didn't wait while the interrogation was taking place. They were certainly never used as they were after Miller's visit to enhance the interrogation effort. Ever.

SCVTV: During or after Gen. Miller's visit, what was your understanding of what he expected the MPs to do with regard to interrogations? And since he's not in your chain of command, how did you take his — what would you call it, advice?

Karpinski: Well, I couldn't even call it advice, because he was dictating that there were going to be changes made at Abu Ghraib. First, he told me he was going to take Abu Ghraib, and I told him that Abu Ghraib was not mine to give him. And he cleared the room and he told me that we could do it his way, or we could do it the hard way. And I said to him, "Sir, I'm not being difficult; I am telling you, Abu Ghraib is not mine to give you. It belongs to the CPA, the Coalition Provisional Authority. If Ambassador Bremer relinquishes control of that facility to you" — he said, "Ric Sanchez said I could have whatever facility I wanted, and I want Abu Ghraib, and we're going to train the MPs to work with the interrogators."

I said, "Sir, the MPs have never worked interrogation missions. It is not like it is down at Guantanamo Bay." I said, "I've been down there" — I visited one time — "and you have 640 prisoners and 800 military police personnel." Two MPs escort every detainee when they leave the cell. They're in leg irons and hand irons and a belly chain. I said, "We don't use leg irons and hand irons and belly chains. The MPs don't feel that it's necessary to move our prisoners around that way."

He said — you know, again, he's waving his arms at me, as if he is dismissing me — and he is saying, "It's not going to be your concern. I'm leaving a CD, a compact disk, with training information, and I'm leaving printed material. They're going to get all the training they need, we're going to select the MPs who can do this, and they're going to work specifically with the interrogation team."

SCVTV: Who selected MPs to do this?

Karpinski: Well, after Gen. Miller left — because he was not listening to anything I was saying — he went in, apparently, to brief Gen. Sanchez on what his plan was. I made sure that my battalion commanders knew that Gen. Miller was going to be leaving training information, that they needed to find out what that was, because the MPs were going to be working specifically with the interrogation team. And every couple of days, I'd have the battalion commander or the operations officer call me and say, "Ma'am, have you heard anything about this?" And I said, "Not anything from me, ask the MI (military intelligence) people."

SCVTV: Did somebody select MPs to work with MI people at that time?

Karpinski: Not to my knowledge, but it is unusual, the way that the MPs ended up working in cellblock 1A and 1B. Because in the military, you would normally task a first sergeant with the mission. And the first sergeant then would say, "OK, first squad, or first platoon, or whatever part of the organization, you're going to be doing cellblock 1A or 1B, you're going to be working with the outside compounds," whatever. It's up to the first sergeant, because the first sergeant knows the strength of the different squads. That didn't happen. Because it was two from the first squad, three from the second squad — that company hadn't even been in the mission at Abu Ghraib for very long when these photos allegedly were taken.

So I know, sincerely, I know in my heart, that these MPs were instructed to do what they did, what has been widely published in photograph form. And they believed that the orders that they were being given, were being given by people authorized to give them those orders.

SCVTV: Did you ever see what was on the CDs that Gen. Miller left?

Karpinski: No. As a matter of fact, I asked the MI brigade commander, Col. (Thomas M.) Pappas, if he was ever going to conduct training with this information that Gen. Miller left, and he told me, he said, "Ma'am, he didn't leave any information with me." He said, "We're supposed to have these interrogators that he's sending up from Guantanamo Bay, and they're going to give some kind of training to my interrogators and to your MPs."

SCVTV: Is it correct that Gen. Miller led a 17-member team of interrogators from Guantanamo Bay?

Karpinski: That's correct. I asked — he brought a JAG officer with him, and I said —

SCVTV: He, who?

Karpinski: Gen. Miller. One of the members of the team was a JAG officer, a lawyer from down there. And I said to her — she was a lieutenant colonel, I believe — and I said to her, "You know, we're having problems with releasing some of these prisoners. What are you doing?" And she said, "Oh, we're not releasing anybody." And I said, "What's going to be the end state?" And she said, "Most of these prisoners will never leave Guantanamo Bay. They'll spend the rest of their lives in detention." And I said, "How do they get visits from home?" She said, "These are terrorists, ma'am. They're not entitled to visitors from home."

I was stunned. I thought, we'll never get out of Iraq at this rate.

SCVTV: Your MPs were trained, were they not, in the application of the Geneva conventions?

Karpinski: Absolutely.

SCVTV: How was that training delivered?

Karpinski: Well, see, they were trained and they were validated at what they call mobilization stations and deployed before I even knew that I was even going to take command of the 800th MP Brigade. So all of that was orchestrated and approved and validated before those units deployed over to Kuwait and then subsequently to Iraq.

SCVTV: So those would have been classes that they took stateside?

Karpinski: Right. But — it's not only, get to the "mob" station, get a class; they're trained throughout the year and it's part of the qualifications. And in addition to that, my brigade JAG officers and my battalion JAG officers would routinely do refresher training with them, to remind them of — and a lot of times the MPs would go to the JAG officers and say, "What are we doing with the Iraqi criminals? Are they entitled to the same things?" Because their prisoners are asking questions. And the reasons they were asking questions was because every prisoner was provided with a copy of the Geneva-Hague conventions in their language. So they knew what their rights and privileges were.

SCVTV: Every prisoner?

Karpinski: Every prisoner.

SCVTV: Was given a copy of the Geneva conventions?

Karpinski: Yes. And it was posted on the wall of the cellblocks, and it was posted in each one of the compounds. Even, I mean, the concertina wire — each compound had a compound representative who could speak some English, and if they had any questions or concerns, they would bring the questions to the NCOIC, the noncommissioned officer in charge of that particular compound. That's the way it works.

SCVTV: A month or two after Gen. Miller's visit, the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross) spent a lot of time in the prison system — where? At Abu Ghraib? Other prisons?

Karpinski: The ICRC routinely visited all of our facilities. And I will tell you this, that not only at Camp Bucca during, when the EPWs were being held, but every one of our facilities, and we welcomed them into our facilities. Because it was another set of eyes. We never wanted to communicate to the ICRC, or anybody else from any of the other humanitarian organizations, that we were hiding anything, or that we were not being up front with them.

Look, we were in the middle of a hostile fire zone, conditions were austere, and it was about 140 degrees at the heat of the day, at the highest point of the day. They understood that. But they also knew that we were doing everything we could to make conditions acceptable for our detainees and for our soldiers.

SCVTV: The ICRC report didn't go public until it was leaked sometime after the Taguba report was leaked. The ICRC took some heat in the foreign press for keeping its findings secret and sharing them only with the U.S. Army.

Karpinski: That's correct.

SCVTV: What did the ICRC communicate to you last fall?

Karpinski: The mechanism for them communicating — if there was anything extraordinary, they would come, before they left the location, they would ask to speak to me, or they would come to my office or ask me to come to them. It only happened on two occasions. And neither one of them were out at Abu Ghraib. Both of those occasions were over at the HVD facility, the "deck of cards" facility. And the reason for that was, the conditions were extremely austere there for the first four months of the operation, and the average age of the detainee was higher, it was about 62. So the ICRC had some particular concerns, and we were able to resolve them to them.

But the report at Abu Ghraib, they didn't come to me. They didn't ask me to come to them. I've heard, from several different people, that they did go to Col. Pappas. Because they went into the cellblock 1A and 1B —

SCVTV: And he was the military intelligence commander at Abu Ghraib —

Karpinski: At Abu Ghraib. And when they were in cellblock 1A, Lt. Col. (Steve) Jordan, who works for Gen. Fast, but specifically ran the interrogation operation, escorted the ICRC representatives through cellblock 1A, and they did speak to him.

SCVTV: To Lt. Col. Jordan.

Karpinski: Yes. But neither Col. Jordan nor Col. Pappas relayed any of those concerns to me. And the only reason I knew anything about it was because the report finally made its way through the system at CTJF-7 and it was already reviewed by the military intelligence people and Col. (Marc) Warren, the CJTF-7 staff judge advocate, before they even presented it to me. And as Col. Warren put it into my hands, because he just happened to have a copy of the report with him when we were talking about this, he said, "Don't worry, ma'am, because we're already working on the response to this report." And I turned to Col. Pappas and I said, "Gee, that's kind of convenient; when we had the responsibility of responding to these reports, my battalion commander and my JAG would have to put the draft together for my review. You get one visit out at Abu Ghraib and you get a whole team of people putting a response together for you."

SCVTV: I understand there was a meeting in November with Gen. Sanchez and Col. Pappas and there was a reply to the ICRC report, and apparently the reply bore your signature?

Karpinski: They told me that — the reason they showed me the report at all was because Col. Warren explained that even though the prison was under the control of Col. Pappas at the time, when the visit occurred, it was actually under the 800th MP Brigade, and rather than make an issue of them transferring the prison to the military intelligence command, they just wanted me to agree to sign the response.

Essentially my JAG officer, my judge advocate general — I had several of them — they reviewed the first attempts at responses and they were in total disagreement.

SCVTV: In a nutshell, what did the response that you signed, say?

Karpinski: Well, the first draft of the response said that — it was very limiting to the ICRC, and it was suggesting that they schedule time when they were going to be in cellblock 1A or B; that these were security detainees that were awaiting or undergoing interrogation or isolation, and their dropping in, in an unannounced fashion, could interrupt the process and limit or reduce the value of any isolation underway. So my JAG officer said, "No way. We're not putting any limitations on the ICRC." If you want to choose words that say, "we would prefer," or, "it might enhance the value of isolation," give them an understanding — and the military intelligence people didn't want to say that. So, I mean, they went back and forth over the correct way to respond to their concerns.

SCVTV: You mentioned that you were no longer in command at Abu Ghraib when that letter was signed —

Karpinski: I was no longer in command of Abu Ghraib when that letter was signed. That's correct.

SCVTV: Lt. Gen. Sanchez on Nov. 19 issued a fragmentary order, or FRAGO, essentially — well, how did you perceive it? Did you understand it to mean that Abu Ghraib was being taken away from you and put under the command of military intelligence?

Karpinski: Well, at that time, yes. Because — and I'll tell you why. Because at that time, since the mid part or late September, the military intelligence people had been increasing the population, considerably, of security detainees being held out there. Our outside compounds, as we referred to them, our general population compounds, were completely security detainees awaiting or having completed interrogation. And cellblock 1A and B, our maximum-security cells, were not only occupied exclusively by military intelligence detainees, but they were being run by military intelligence interrogation teams. With the exception of the detention piece, my MPs were still doing that.

So we wanted to move towards getting our Iraqi criminals into hard facilities anyway, and the population out at Abu Ghraib was at least 90 percent security detainees. So it was no surprise to me that — and Col. Pappas was living out there — so it was no surprise to me that they actually wanted to take over the whole compound.

I asked Col. Pappas how he found out about it, because I wasn't even in Baghdad when the FRAGO was cut. Nobody talked to me about it; nobody said to me, "This is what we're going to do or why we're going to do it," so I said, "How did you find out about it?" He said, "Ma'am, I found out about it the day after the FRAGO was published." And I said, "Did Gen. Fast talk to you about it?" And he said, "Oh, no, ma'am. She wanted Abu Ghraib, and she wanted the interrogation operation run a certain way, and this was her solution."

SCVTV: When did some higher-up talk to you about it?

Karpinski: Never. I went to Gen. Fast and I said to her, "You know, this is news to me, and apparently it's news to Col. Pappas." And she said, "Oh, it's not news to Col. Pappas. He understands why we're doing this. Because we're going to run interrogations the way we want them run." And I said, "Well, I talked to Col. Pappas about the responsibility of the MPs," and she said, "That's administration." She said, "You handle the administrative part of it any way you want. You want to still rate them, you want them under your control, that's up to you."

And this is never a good thing. Officers and soldiers are entitled to a clear line of command. And they didn't have it. So we already had a bad situation with our chain of command — did we belong to CFLCC or did we belong to CJTF-7? — and now they were just layering another problem on top of it.

SCVTV: So what was your understanding of how command was supposed to work?

Karpinski: Col. Pappas and his XO (executive officer), a major by the name of Williams, both told me, probably within a week of that FRAGO or 10 days of that FRAGO being cut, that they wanted clarification, and they got it from Gen. Fast, and Gen. Fast told them — not suggested to them, told them — that they were in charge of Abu Ghraib. And Col. Pappas told me, "Ma'am, I'm learning more about detention operations than I ever thought I'd ever want to know. (Lt.) Col. (Jerry) Phillabaum is doing a great job. He's spending time with me every day, explaining why they do things a certain way and why they can't do other things."

So that was what Gen. Fast told Col. Pappas. That was Col. Pappas' understanding, and subsequently it became my understanding.

SCVTV: So you were informed that military intelligence was in charge of Abu Ghraib — you were informed by the military intelligence officers themselves.

Karpinski: That's correct.

SCVTV: How did you respond? What instructions did you or your subordinates then issue to the MP guards?

Karpinski: I talked to Col. Phillabaum and to his XO, who is a major, Mike Sheridan, and to the operations officer, and I told them that administratively, they were still under the 800th MP Brigade, but the instructions would be coming from Col. Pappas; that the vast majority of the prisoners out there were security detainees; and they all had the same understanding. I mean, it was obviously something that they had talked to Col. Pappas about. And I told them, I said, "This is what we're going to do: We are going to transfer all of the civilian criminals that are remaining out here, we're transferring them to other facilities." Because, you know, never the two shall meet. "This program out here is — there is no way to release them; there's going to be 15,000, unless Gen. Fast gets this thing under control, so whatever Col. Pappas wants you to do."

SCVTV: Not that you necessarily could have changed things, but did you instruct your subordinates to answer to Col. Pappas?

Karpinski: I guess I implied it, yes. I didn't tell them not to. But let me give you an example.

I was out there visiting the MPs on Christmas Day, and when I was walking through the compound, a couple of the NCOs saluted me, which was different than anything I'd ever seen before. So I said, "What's going on?" And they said, "Oh, Col. Pappas said we have to put courtesies in place." I said, "Hold on a second. I don't want my head blown off, OK?" And they said to me, "Ma'am, we understand, but" — I said, "I'll talk to Col. Pappas." Which I did. And I explained to him, "When I'm out here, I do not want them saluting me, and if anybody reports to you that the MPs were not saluting me, I don't want to get into trouble. This is why." And he said, "Oh, oh. That sounds like a good point." One day, these guys are going to be back out on the street again, and the last thing you want them to know is that the MPs, the soldiers, were saluting you, because then your head becomes very valuable. He said, "You know, that's a good point." I said, "Nowhere in detention operations do they salute in a compound." He said, "Oh, that's something else I've learned now." I mean, just like that.

They also did a capabilities demonstration that day, one of his MI long-range surveillance teams, and they had helicopters assigned. So they did a capabilities demonstration to dissuade, I think, the prisoners from any ideas of an escape or anything. And they do that by rappelling out of helicopters. So they told me that they were going to do it about noontime, and they had rehearsed it, and they were going to do it over by the wall, they had the spots marked and everything. Well, we were out there visiting, and these helicopters came in.

Now, one of the helicopters went directly to the right spot. The other helicopter decided to hover over one of the compounds. And it blew three of the detainees' tents down and scattered clothes that they had just washed all over the place. So I called Col. Pappas and I told him what I thought about that, that that kind of negligent behavior causes prisoners to get excited. And my MPs are the ones who have to deal with it afterward. And he said, "Oh, ma'am, I'm sure it was just a mistake." I said, "How do you make a mistake? A mark on the ground close to the wall, or hovering over compounds where there's obviously detainees? How do you make that mistake?" He said, "Well, I wasn't in that helicopter." I said, "You tell him, if he ever does it again, then he's going to deal with me."

SCVTV: So the MPs truly were answering to Col. Pappas and military intelligence.

Karpinski: Yes.

SCVTV: All MPs at Abu Ghraib?

Karpinski: Yes.

SCVTV: And this only applied to Abu Ghraib, correct?

Karpinski: Right.

SCVTV: The FRAGO.

Karpinski: Right.

SCVTV: And that date was Nov. 19.

Karpinski: That's correct. But prior to that, Pappas had already been living out there, and he was running operations in cellblock 1A and B.

A soldier walks through the cellblock that Saddam used as his death row inside Abu Ghraib, June 24, 2004. AP Photo

|

|

SCVTV: How often did you visit Abu Ghraib prior to Nov. 19?

Karpinski: At least — it was in Baghdad, so I was out there probably two or three times a week. And some of that was because we were escorting visitors or delegations out there.

But I — if I was on my way back from one of my other locations, I would routinely stop in to see how things were going. Because it was a mess. And we were getting more detainees and they were getting more restless because there was no legal representation for them. They didn't even know why they were being held, in some cases. It was a mess.

SCVTV: After Nov. 19 — you're still the commander of the military police personnel who are at Abu Ghraib, even though they're not under your command.

Karpinski: That's correct.

SCVTV: So how often after Nov. 19 were you at Abu Ghraib?

Karpinski: Less. Much less. Probably — I'd stop in one day a week. Maybe two afternoons a week. Much less time. Because I did not want to get at odds with Col. Pappas. He knew that I was senior to him but he didn't work for me, and I routinely talked to the battalion commander and the XO out there, and I told them, "If there's anything that, you know, you need to talk to me, you still have a clear line of communication with me." But they were, as the XO told me, "He's trainable. We're teaching him what he needs to know."

SCVTV: Was Col. Pappas in Gen. Sanchez's direct chain of command?

Karpinski: I believe he must have been, because Col. Pappas worked for Gen. Fast, and Gen. Fast worked for either Gen. Wodjakowski or Gen. Sanchez.

SCVTV: The CD that Gen. Miller left behind in September — you don't know whether it was disseminated.

Karpinski: That's correct. And Col. Pappas himself told me he never saw the CD.

SCVTV: To your knowledge, after Nov. 19, what were the instructions from Col. Pappas to MPs in the context of their involvement with interrogations?

Karpinski: To my knowledge there was none. He left it to the interrogation teams and the interrogators to tell the MPs what they needed them to do.

SCVTV: The statement of one of the civilian interrogators, Steve Stefanowicz, has been leaked to the press. It indicated that the interrogation teams would leave written instructions for MP guards. Do you have any personal knowledge of that kind of instruction?

Karpinski: No. And I will tell you that I find that doubtful, because I still would go through the prison facility, and I would drop in on the MPs at cellblock 1A or B or anywhere else at Abu Ghraib, and I'd look at their books, their SOPs, I'd ask them if there (were) any questions. I'd walk down the hallways and talk to some of the different detainees, and I never saw a set of instructions. I never saw written instructions from interrogators. I just didn't. And the MPs never told me that they had instructions from the interrogators. I do know that the interrogators told them verbally, because I read the Taguba report.

SCVTV: There has been talk about special "interrogation rules of engagement," which aren't out of the military playbook. Evidently, under these rules, if interrogators wanted to use particular techniques, they had to get the personal approval of Gen. Sanchez.

Karpinski: That's correct.

SCVTV: Did you see those "interrogation rules of engagement" posted on the walls at Abu Ghraib?

Karpinski: No, I did not. I never saw a list of rules for interrogators. When they said that they were posted on the walls, I said, what wall might they have been posted on? In the military intelligence operations office? Because they weren't posted in the cellblocks.

SCVTV: Col. Pappas has testified that those rules were developed as an outgrowth of Gen. Miller's visit in September. Do you have any knowledge of that?

Karpinski: Well, that would be consistent with what Gen. Miller said, that he was going to give them the instructions. But he talked about his interrogators, the ones that he was going to send up from Guantanamo Bay and the ones that he brought with him, that they knew what the rules were, and that they would share them with the interrogation team.

SCVTV: When did you first learn of the abuses?

Karpinski: I was up in another location outside of Baghdad. We had a different kind of security mission. And it was about an hour and a half away from Baghdad. We were meeting with the leaders at that location, and we finished the meeting — they liked to meet late at night. So we finished the meeting at about 11 o'clock, 11:30 at night. I went back into the operations office up there and I checked my e-mail, and there was an e-mail there from the CID (Army Criminal Investigation Division) commander. So I opened it up and I said, what the heck is this? And it said — that was the first time, and it was almost as if he thought of me as an after-fact or an afterthought.

SCVTV: This was when?

Karpinski: This was on the 16th of January. And it said, "Ma'am, just wanted to let you know, I'm going in to brief Gen. Sanchez on the progress of the investigation at Abu Ghraib. This is the one about the potential — or, the allegations of abuse, and there's pictures." And really, my mouth dropped open. I said, "What is this?" So I called to my operations officer, who was back in Baghdad. He said, "I don't know anything about it." And I said, "We're coming back tomorrow."

And we went out to Abu Ghraib, and all of the people that would have been knowledgeable had been suspended and the MPs had been removed from their positions. They wouldn't allow me to speak to them. The people that were sitting — the MPs that they used to replace them were obviously shaken by all of these allegations. And they said, "Ma'am, we heard the rumors, but I don't" — the one NCO told me — "Ma'am, I didn't see anything. I worked in here a couple of times and I can tell you, we were never involved in anything like they're talking about."

SCVTV: This is literally two or three days after the photos were brought to the attention of someone —

Karpinski: Right. Of Gen. Sanchez.

SCVTV: So this MP guard, Spc. Joseph M. Darby —

Karpinski: He was trying to make copies — this is what I was told by the CID commander — this MP was trying to collect photographs from their tour in Iraq. They'd spent about eight months at a different location, down with the multinationals, and he wanted to collect — make copies of photographs that other soldiers had taken. So he asked his fellow soldiers in the unit, "If you have any pictures on disks, can you loan them to me? I want to make copies." So he had this one disk, and it had these pictures, and he opened some of them up, and he was surprised.

So he went back to the NCO that had given him this disk and he said, "Hey, man, you know, I don't know what this is about." And he said, allegedly, "I'll take care of it." Well, nothing happened. So he started to get nervous, I guess, and he felt an obligation, so he took the disk and gave it to the CID resident officer who was out at Abu Ghraib — they have small office out there — and said — slid it under the door because it was late at night — and said, "If you need to get in touch with me, I'm Spc. Darby."

So the CID agent opened it up and called his boss right away, the colonel, and the colonel went out there and got the disk and took it to Sanchez. And that was on the 13th of January.

SCVTV: Were you aware of any allegations of abuse that were separate from what was depicted in the photographs?

Karpinski: No. The only time I saw any reference to anything was in that ICRC report. It was either the last week of November or the first week of December when that impromptu meeting took place and they gave me this report.

SCVTV: So there was an indication in the Red Cross report —

Karpinski: In that report, yes, that a detainee who was in isolation was told to wear women's underwear on his head. And when I said to Col. Pappas, I said, "What is this all about?" And one of his operations officers said, "Oh, ma'am, I told the commander to stop giving the detainees those Victoria's Secret catalogs because they'll make up stories like this." And I said to all of them, I said, "I don't think the ICRC would appreciate that kind of response."

SCVTV: So you communicated that to Col. Pappas —

Karpinski: Yes, I did.

SCVTV: Expecting him to take care of it?

Karpinski: Well, he — they then went into this relatively elaborate explanation that detainees — every one of them is innocent and they'll make up all kinds of stories. And they said, "Where would they get women's underwear?" I said, "Is there any truth to this?" And they immediately jumped to — the MI people said — "No, no, absolutely not. I mean, where would this come from?" That's the kind of thing that they were saying. I can't say they gave an absolute, like "no truth at all." They sidestepped it.

And Col. Warren, the JAG officer, was in there very quickly saying, "You know, this is true with all detainees; if you put them in isolation then they'll say that they've been tortured and beaten, and, you know, we've heard those reports before." And I said, "But there has never been foundation."

We know that, too. Now, I do know that when you put a detainee in isolation, a lot of times, they want to take control. So they'll take all their clothes off and they'll refuse to put them back on. And sometimes the interrogators take their clothes away from them so they don't feel like they're in charge. "OK, you don't want to wear your jumpsuit? We're going to take it away from you," that kind of thing.

But, I mean, I have never heard of them stripping anybody naked, and that was, you know, implied in the report from the ICRC, as well.

SCVTV: When the ICRC made this allegation in late November or early December, did you talk to anybody besides Col. Pappas? Did you talk to your own MP personnel directly about it?

Karpinski: I talked to the XO. He called me, as a matter of fact. He said to me, "I've gone and spoken to the MPs, and for this particular visit, Col. Jordan and people from the MI command were escorting them. The MPs said that they do know that occasionally a detainee will take his clothes off, but they have no knowledge about women's underwear on their heads or anything else."

So I'll tell you, when I saw the pictures for the first time — and I saw the pictures for the first time on the 23rd of January — I was shocked. I felt sick to my stomach. Because of the expressions on the military police personnel's faces. I was shocked that they would photograph themselves doing such criminal things.

And not that they were torturing these people, but this was absolute humiliation of a sexual nature, and their faces seemed to reveal that they were enjoying it. And I was sickened by that behavior. And I said, out loud, to the CID commander, "What would make a soldier do this? What would make a solder do this?" And I said it three or four times in frustration, I guess, just absolute shock. And he said, "Well, ma'am, that's what the investigation is going to tell us."

SCVTV: A lot of dates have been thrown around — October to December, November to January — when these things were supposed to have occurred. We've identified Nov. 19 as a watershed date; that was when MI took control at Abu Ghraib —

Karpinski: Right.

SCVTV: Do you know whether the things that were depicted in the photographs happened before Nov. 19 or after Nov. 19?

Karpinski: Well, I was, you know, immediately going to those — I even asked the CID commander, "What's the date on the pictures?" And he said, "Well, we're trying to work it out, but we believe that it was sometime in late October or November." And I said, "Well, the MPs that are in these pictures haven't been at Abu Ghraib all that long." For them to get up to Abu Ghraib and go to work, and decide that they're going to abandon everything that they know to be right, and start taking pictures like this? I said, "This doesn't make any sense at all."

And I've clarified that by checking with my operations people, since then, about dates. And that unit would have been at Abu Ghraib for not longer than three weeks. So, (they) served successfully in another location for about eight months, moved to Abu Ghraib — very dangerous location, no doubt that they were prepared, you know, well in advance, by all the people, saying, "Oh, you're going to Abu Ghraib, what a horrible location," and everything else — but that would mean that in three weeks, get their feet on the ground, go to work, and decide that they could do these things and get away with it because they felt so comfortable with their surroundings? I don't believe it.

SCVTV: Where were they the eight months prior?

Karpinski: They were down with the multinationals in (Al) Hilla and Ad Diwaniyah, which is in the southern part of Iraq.

SCVTV: Were they doing prison duty?

Karpinski: Yes. Iraqi prisons.

SCVTV: Do you have any indication that they did the same kinds of things there?

Karpinski: No. As a matter of fact, I called the battalion commander the next day and I said to him, "Any indications that they were out of control?" He said, "Absolutely not, ma'am. They served fine, they were dedicated; they often worked longer hours because we were short people." I said, "Any indication at all?" He said no. He said occasionally a soldier would get frustrated with the 365-days program but, you know, other soldiers would get him back on track and everything. And he said, "No, nothing like this."

SCVTV: There have been rumors of alcohol abuse among the MPs. Was alcohol flowing freely at Abu Ghraib?

Karpinski: I — not to my knowledge. And, look. We — not under my control, but I will tell you that the 800th MP Brigade had its share of problems early on with people consuming alcohol and getting caught. And that's a violation of General Order No. 1. So around the holidays and, because they were being mortared every night, they were understaffed, they were not getting a break and there was so much work going on out at Abu Ghraib with all these contractors coming in and everything, you know, commanders knew to be particularly aware of that possibility.

But Abu Ghraib was a closed facility. It wasn't like you could go to the package store and pick up a bottle of booze. It would take a concerted effort for soldiers to get alcohol and then to consume it. I just — now, on the other hand, the military intelligence people were pretty much free to come and go. And if they were bringing booze out there, I wouldn't have been knowledgeable of it unless my MPs were drinking with them. And I just didn't get any reports to that effect.

SCVTV: These pictures — they aren't pictures of interrogations; they are pictures of freakish things that were done to detainees in the hallways, in the hard cells. So there are the pictures, and then there are interrogation sessions, and they aren't the same thing.

Karpinski: No, they are not.

SCVTV: Do you have any personal knowledge of improper interrogations?

Karpinski: No. I observed one interrogation underway one time, and it looked perfectly routine, perfectly acceptable. There (were) three people as part of the interrogation team; one of them was an interpreter; and they had a prisoner in there. He was in his jumpsuit, and he was slumped down in the chair, not being very cooperative — not being uncooperative — but there was no physical contact, there was no roughing up. They were going through the motions of getting information, and I could see it from a one-way mirror. So, I mean, I observed it for 15 or 20 minutes.

SCVTV: We've discussed how the MPs were under the command of Col. Pappas and military intelligence after Nov. 19, and how, after Gen. Miller's visit, MPs were supposed to help with the interrogation process —

Karpinski: Right.

SCVTV: But when it comes to the pictures themselves, are you suggesting that there was a connection between the pictures, or what was depicted, and interrogations?

Karpinski: Well, not being an interrogator — and I can also tell you this, that to my knowledge, the interrogations — because I was there when they were constructing the interrogation facility. So to my knowledge, the interrogations were supposed to take place in one of those rooms, in the interrogation facility, which was outside of cellblock 1A and B.

Now, those pictures, I believe, were staged, or set up — nonetheless, they are humiliating acts, OK? But I believe that they were staged and set up to be used to show to a detainee as they were getting ready to undergo interrogation. And you project that up on a wall, or you show that to them in living color, in 8x10 glossy, or you show it to them on a computer, and you tell them, through the interpreter, this is what has happened to some of your friends —

SCVTV: So you believe the pictures had a purpose, and the purpose was for them to be used to intimidate prisoners.

Karpinski: Yes.

SCVTV: Future subjects of interrogations.

Karpinski: Yes. I do. And I believe that those pictures were planned, were programmed, that they used the MPs to get the detainees out of their cells, and that there was an official set of photographs being taken.

SCVTV: Why do you believe that?

Karpinski: Because — I don't — and I don't mean this to sound anything differently than what I mean — but I don't see interrogation taking place in those photographs. I see humiliation. I see an opportunity for an interrogation team to exploit those photographs in an effort to get information quickly, more quickly and more efficiently, from a new detainee. I mean, if you can get a detainee to start talking within a couple of hours, as opposed to two or three months, then, if this is being used to do that, then that, to me, is enhancing the interrogation effort.

SCVTV: While I haven't spoken with her personally, Pfc. Lynndie England, the young MP who is seen in some of the more bizarre photos, reportedly said in a recent interview that she thought it would be fun to take some pictures.

Karpinski: And I believe that.

SCVTV: What do you think of that idea?

Karpinski: I haven't spoken to Lynndie England, either. But, you know, when I look at possibilities, when I look at, you know, what makes sense — these are sensible people. These are sensible soldiers. And they've proven themselves capable. So what made them go berserk, or whatever you'd want people to believe? Well, they were taking instructions.

Let's say they were taking instruction and they believed that the instructions were being given to them by an authorized person. They're looking at this and they're saying, "You know, there's a photographer over there, taking pictures, and we're not supposed to be taking pictures of detainees, but as long as they are, I guess we can, too." So I would imagine one of the soldiers, one of the NCOs, most likely, flipped out one of those digital cameras, pocket size, and said, "Hey, England, get over there and give me a thumbs-up. Give me a big smile. We need proof of this when we get back home." And when nobody stopped them from taking one picture, then it became a dozen, or maybe 100, or several hundred eventually. "They're not going to believe this back in West Virginia. They're not going to believe this back in" wherever they're going home to.

"Happy snaps" is what they've come to call them. You know, in a digital camera, when you press the button, it will just continue to take pictures until you remove your finger from the button.

SCVTV: You said these happened in late October or early November. Was this an isolated incident? Was it just a few bad apples who were doing this? Did it happen more than once?

Karpinski: I don't know. I believe that they're — it looks like they were all taken on one night, at one setting. And likely, when those pictures surfaced via the CID commander to Gen. Sanchez, he probably was shocked.

Now, I'm not suggesting that there's not a possibility that he didn't know photographs were being taken and that those photographs were going to be used at the leading edge of an interrogation. But when he saw those souvenir photos on personally owned compact disks, he was probably shocked.

And I don't think that this was six or seven bad apples. I think that this was six or seven individuals who may have been specifically selected. Because they were likely to participate. I don't know.

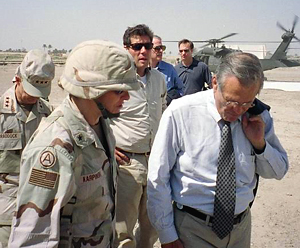

Brig. Gen. Janis Karpinski confers with Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld in

late September 2003, following a visit from the chief jailer at Guantanamo Bay, Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Miller. Karpinski said Miller had been sent to Iraq

to set up a Gitmo-style interrogation operation. Photo courtesy of Brig. Gen. Janis Karpinski

|

|

SCVTV: Last week the Pentagon released memos showing Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld approved particular interrogation techniques for use at Guantanamo Bay. To your knowledge, are there documents showing he also approved particular interrogation techniques for Abu Ghraib?

Karpinski: I did not see it personally, but since all of this has come out, I've not only seen, but I've been asked about some of those documents, that he signed and agreed to.

SCVTV: About Abu Ghraib?

Karpinski: Yes. About using the same techniques that were successful in Guantanamo Bay, at Abu Ghraib.

SCVTV: Those documents have not been released yet.

Karpinski: No.

SCVTV: What can you characterize about them?

Karpinski: I know that Col. Pappas, on three occasions, sent a request to Gen. Sanchez to escalate their interrogations, and that involved using — and he lists them. And in one case he said they wanted to use dogs, and they wanted to increase the length of time that they could be isolated, food deprivation, that kind of — sleep deprivation. And in at least two of those cases, there is a signature of approval from Gen. Sanchez.

SCVTV: And you've seen these documents.

Karpinski: Yes, I have.

SCVTV: When Mr. Rumsfeld tells us that the next set of photos and videos to be released will be a lot worse, what are they going to show?

Karpinski: I have no idea. I have no idea. I can only imagine. Umm, I heard a reference to a video clip of a soldier actually having sex, or what appeared to be having sex, with one of the prisoners. But I have not seen it. I asked the CID commander about it specifically, and he said they heard rumors about it, too, but had not uncovered any such photos at that point.

SCVTV: Four military intelligence people are identified in the Taguba report as having been "directly or indirectly responsible for the abuses" — Col. Pappas and Lt. Col. Jordan, along with two civilian contractors, Steve Stefanowicz, an interrogator, and John B. Israel, a translator. As I believe you know, here in Santa Clarita, John Israel is a local resident.

Karpinski: Uh-huh.

SCVTV: Did you ever know or meet either John Israel or Steve Stefanowicz?

Karpinski: I did meet Steve Stefanowicz.

SCVTV: Would you know John Israel, too?

Karpinski: No. I may very well know him, but I don't know him by that name.

SCVTV: Do you know why Maj. Gen. Taguba singled out these two civilians in terms of being responsible?

Karpinski: No. And as a matter of fact, I will tell you that I saw Steve Stefanowicz out in what they called the intelligence coordination element, which was a separate facility all together. I never saw him during an interrogation, and I never saw him in cellblock 1A or B. Ever.

SCVTV: John Israel was provided to the Army by Titan Corp, which has an estmiated 4,400 translators in Iraq. Did you have Titan translators working for your MP brigade?

Karpinski: Yes, I did.

SCVTV: How does the chain of command work?

Karpinski: We have no control over them at all.

SCVTV: How does it work?

Karpinski: Titan Corp. would — my guy who was the point of contact for the brigade would call them and tell them, "We need six more interpreters." And then he would say, "But here's the limitations: They're going to be working out at, for example, at Abu Ghraib; they won't be able to leave; we'll take care of feeding them, housing them, blah blah blah blah blah," and they'll find interpreters that will agree to those conditions.

And they will remain at the facility — because the interpreters are not vetted successfully. If you get one in there that can speak English and speak the language and he hasn't been vetted successfully or completely — or at all, in most cases — if they leave, they could be giving information to the insurgency or the opposition or whatever.

So that was the only control. But their work schedules or their uniforms or what they did or — we had no control over them at all.

SCVTV: There has been discussion recently that some of these contracting firms are basically acting as employment agencies for the military.

Karpinski: That's exactly what they're doing.

SCVTV: And that may not conform strictly to federal guidelines.

Karpinski: No, I'm sure it doesn't. I was extremely frustrated with it because, you know, we'd look for the interpreter — and we didn't have nearly enough interpreters — but I'd look for one and they'd say, "Oh, he's sleeping." Or, "He doesn't usually come in on time." And we couldn't fire them, we couldn't — and they were so — the military in Iraq — was so desperate to get more translators that they were — the divisions were asking for more and more and more translators, and they were the priority, and they didn't have nearly what they needed. So these people, these contracting — Titan Corp. and I guess there were similar corporations — they had practically a blank check.

SCVTV: There are chain of command issues, too —

Karpinski: There was none for them.

SCVTV: Reading through the Army regulation, "Contractors Accompanying the Force," evidently the contracting company is supposed to provide a job site manager to supervise the civilian employees, and the Army would designate a liaison to confer with the manager —

Karpinski: Right. Or Col. Jordan would.

SCVTV: So in the field, when contractors were assigned to the MP brigade, would the MP person in charge ever give direct orders to civilians?

Karpinski: No.

SCVTV: How did it work?

Karpinski: Well, if there was a problem with the interpreter — or, like, for us, because we didn't have interrogators — but for interpreters, they would call my point of contact in the brigade and he would try to get it resolved. And the job manager, or the site manager, was down in the CPA building. They were never out at the site. Never.

But the battalion commander or the company commander would voice those concerns to my lieutenant commander, who would work on getting it resolved. But even documentation to poor performance or poor English language skills or whatever, it was just a document. Nobody was ever fired.

SCVTV: And as you've mentioned, not all the translators were Americans who were shipped over there. A lot of native Iraqis were among the civilians.

Karpinski: Right. And then — initially, the first ones that were brought over were from the United States, from throughout the United States. They were paid very, very well. Which is why they were — like a lot of contractors over there, they agreed to work under those hostile fire conditions because they were paid extremely well.

SCVTV: How well is extremely well? What did they earn a month?