|

|

|

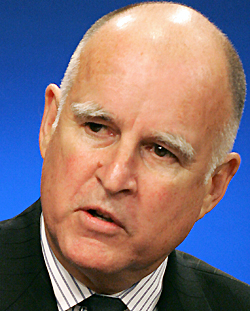

SCV NEWSMAKER OF THE WEEK:

Edmund G. "Jerry" Brown

Mayor of Oakland

Former California Governor

Interview by Leon Worden

Signal Multimedia Editor

Sunday, October 31, 2004

(Television interview conducted October 27, 2004)

"Newsmaker of the Week" is presented by the SCV Press Club and Comcast, and hosted by Signal Multimedia Editor Leon Worden. The program premieres every Wednesday at 9:30 p.m. on SCVTV Channel 20, repeating Sundays at 8:30 a.m.

"Newsmaker of the Week" is presented by the SCV Press Club and Comcast, and hosted by Signal Multimedia Editor Leon Worden. The program premieres every Wednesday at 9:30 p.m. on SCVTV Channel 20, repeating Sundays at 8:30 a.m.

This week's newsmaker is Oakland Mayor Edmund G. "Jerry" Brown, governor of California from 1974 to 1982. The interview was conducted Wednesday. Questions are paraphrased and some answers may be abbreviated for length.

Signal: Welcome to Santa Clarita.

Brown: Very nice to be here. It's been a long time.

Signal: You've been out stumping with all of the other California governors, past and present, to defeat Proposition 66.

Brown: Yup. And the reason for that is, 66 is deceptive. It sounds reasonable until you really understand the implications. It's a far-reaching, sweeping change in a very complex sentencing structure.

Signal: We're talking about three strikes.

Brown: Three strikes. When you alter laws like burglary, gang crime, arson, witness intimidation, that affects not a few hundred people, but tens of thousands of inmates. And you don't know, are they ax-murderers? Are they child molesters? Are they arsonists? What are they?

When you read the ballot argument, it just talks about, well, you should have to have a violent felony in order to get a third strike. The way they got Al Capone was with income tax, which wasn't — at least by today's standards —Ưa violent felony or even what we call a serious felony. And yet he had a life of crime and murders. And under the three strikes — which, by the way, last year there were less than 405 individuals given the third strike, out of 200,000 convictions. Hundreds of thousands of people are being convicted — more are being arrested — and by the time you get down to the worst of the worst, it's 400. And half of those are what Proposition 66 wants to let out.

It's a wholesale release of people, many of whom are very dangerous, have incredibly bad records, and because of the misguided understanding of three strikes — this thing (Proposition 66) has been written by a father, a very wealthy auto dealer, to get his own son, who had killed two people, out of prison, and a lot of people don't get this.

But now the governor's on it; all the former governors are opposing this; and that's why I've joined the campaign — because we in Oakland do have a lot of crimes, and the last thing we need is some of the most dangerous people coming back into the community after we all thought they'd been locked up for the rest of lives.

Signal: On your Web site, you say crime in Oakland has dropped 30 percent since you were elected mayor in 1998. Are you worried about the release a bunch of criminals back into your community?

Brown: Well, I can tell you this. Some district attorneys were tougher than others. In Alameda County, I think Tom Orloff — that's where Oakland is — has been pretty careful. So the ones that he gave a third strike to, he really thought about it. He thought these people should be locked up for the rest of their life.

Half of them are the ones that are coming out. Fifty percent. So we're basically — to vote yes on this, you have to believe that the 58 prosecutors, the district attorneys in California, have been wrong 50 percent of the time. Because there are 7,000 people locked up under this life sentence, and Proposition 66 lets half of them out. I mean, it's an extraordinary claim to foist on the people of this state, and that's why I feel so strongly that people to read the text and hopefully they're going to vote no.

Signal: The Yes-on-66 people say it's not true that 26,000 second- and third-strikers will be released right away; instead, they'll be retried and resentenced. Are we really going to be flooded with criminals overnight?

Brown: Yes. First of all, we know that at least 3,500 of the worst of the worst are coming out, and that's bad enough. There's a group here of convicted criminals that's been laid out in this Insider magazine — you know, "(Meet) Your New Neighbors." It's not very nice. It's dangerous. (There's one) guy who raped his mother; another guy tried to burn his own kid.

Signal: These people are going to get out?

Brown: They're going to get out.

Signal: Wasn't their sentence for their last crime good enough to keep them in?

Brown: See, what happened is, they were convicted (of), let's say, a burglary, and if nobody was in the house, and that was the trigger to give them life sentencing, they'll be released even though they might have been convicted of a murder.

Twenty years ago, the average time for a murderer was 10 years. The minimum time was 7 years. So a lot of the people who murdered, who raped, got out a lot earlier. And they didn't stop. They didn't stop doing that stuff, but they weren't caught. Now they get caught and they're in under the three strikes law for a burglary, a gang crime, an arson or something like that, or as this guy ... what is his name? Kenneth Parnell. Parnell tried to buy a 5-year-old to make him his slave. And this is the guy that already captured a boy and kept him for five years. OK. That is not viewed as a serious enough crime to be a third strike (under Proposition 66). That is why he's on the list to be automatically released.

Now, you mentioned that the thousands — that comes about because (of) second strikers, who have very serious crimes, not in for the life, but in for an extended period — they, under rules of criminal law, will be eligible for release because what they did was worse for what third strikers are being released for. And whenever you have that kind of an unfair, unequal situation, under equal protection and under interpretation of the criminal code, judges will interpret the intent of the law as to let out those who did less, but are being kept in longer than this odd 66 lets out.

So based on that legal analysis, 58 district attorneys out of 58 say the retroactive — that means, going back to cases that have already have happened, already the people are in jail, that class — the two-strikers — that's about 25,000 additional people who will either be let out or be given substantially shorter sentences. And that's where we get the prediction that these people come out.

And it's not just about resentencing. Some may get a resentence, but that resentence could be as short as three months, six months, a year, two years, or maybe they have to go out right away. That's what we're looking at. It's a hodge-podge. But it's sweeping, in the consequences that nobody quite knows what is. The D.A.s are figuring out — that's why they make one of these papers, they list all of these (criminals) — one guy, you know, tortured his dog and cut off his head and he had a terrible record. And he's going to be let out because I guess cutting a dog's head off is OK. But what it does is, this wasn't an accident. This was a brutal, systematic, intentional, prolonged torture, and that then is an indication of what this man is capable of. And he, because of his record, got his third strike.

Those are some of the people that are coming out. And whether it's 30,000 or whether it's 20,000 or whether it's 5,000, the people that are being released are the last people — now, a lot of these people say we've got too many people in prison; well, if the problem is too many people, and a lot of good people believe that — the last group you want to start with are the worst.

If you want to reduce the prison (population), you want to take 5,000 or 10,000 people and put them on the street, you would go and say, let's go in rank order. All 164,000 prisoners. Those who are the least dangerous, we'll let them out to save some money and prison space. OK, fine. But they did just the opposite in this Proposition 66. They said, in effect — they don't tell you that, but this is the implication — Who are the worst possible people? Who are the people that the D.A.s felt should never walk the streets again? They're the ones that are coming out.

And they're coming out because the mechanism is — take a crime like a gang crime or burning down a commercial building or attempting to molest a little kid or burglarizing a house before somebody gets home. That's now called un-serious (under Proposition 66). It's not serious. Because it's off the list of serious, it's not a third strike. Because it's not a third strike, these very dangerous individuals who'd finally been put away are now let loose.

These 400 that are the worst — and by the way, the D.A.s don't have to give them a third strike. And the judges don't have to accept it. So that's the great difficulty here. You've looked for the worst; you let them out first. It's kind of completely upside down. I think the reason for it is that the car dealer who wanted his son out, he had to get some allies among the various prisoner rights groups or whomever, the defense lawyers, and they know these guys get out. Most of them all are coming back, and when they come back, they're going to have more business.

Signal: Isn't there anybody who has been sent to prison under three strikes who doesn't really belong there?

Brown: I'm sure there are. First of all, there are people who are innocent. And we'll figure that out. We know. There's a case of this, on a DNA case where they found a guy killed 10 people and a man named Jones was in wrongly. So, yeah, we make mistakes. I don't think we make that many, but they do make mistakes. All right, that's true. Then you find other people who reform their lives, and they work their way out. There is a way to deal with that. You can have the governor commute people. And governors do do that. Schwarzenegger is doing more than Gray Davis.

Secondly, if you really want to get at the prison business, a hundredth of the problem — about 100,000 people come out of prison every year. And we have 164,000 in. So how come we keep so many in? Because they come out, and they go back in. They come out, and they go back in. And so if you really want to deal with this problem, you'd find a way to train these people. You'd give them incentives for getting out of prison. When they learn a skill, when they learn to control their anger, when they learn to take care of their drug problems, then you let them out, with a plan. They have to develop skills. It doesn't always take a teacher. They can learn it on a computer, and then when they get out, they get a plan. They make their way into society.

For the most part, it's a terrible system of people committing crimes, having no skill, being locked up, and let out. The ones that Proposition 66 deals with are the worst of the worst, and in most cases, they're coming back anyway. So everybody is saved all the grief of having to go through another victimization, maybe another murderer, another burglary, another robbery, and have them then convicted and go back into prison. It just keeps them there. Because they've proven by their behavior that that is their M.O. — their modus operandi is a criminal act.

Something I didn't realize before I was mayor, when I restarted to learn this stuff — a lot of people, I'm sure the majority in prison, don't have any other skills except robbing banks, burglarizing, selling dope —

Signal: Making license plates?

Brown: Well, they're probably stealing license plates. They haven't developed skills. They aren't going to go work for an insurance company. They're not going to get a job on the docks. They're not going to get a job as a bus driver. They're not. And that's why they keep coming back. If they come back enough, and they commit certain crimes, they get locked up under three strikes. That's the deal.

I'm not saying there aren't some reforms — I think the prison system is by no means perfect. There are a lot of changes that need to be made, and certainly, if I'm attorney general, I intend to work for district attorneys, with defense lawyers, with criminologists, and figure out things that can make the whole criminal justice system better.

But on the whole laundry list of things to do, I would say letting out the worst — which is, like, three and a half percent of the whole prison — would be at the bottom of the list that you never get to, because trying to do the things you could do, and are important to do, are challenging enough. And this is just kind of an easy, nice-sounding thing: "Oh we just changed a few laws, and we let some people out." No. It's dangerous. It's ill-conceived. And the consequences are not known — well, except to the prosecutors and the investigators. So I think the vote here should be caution. When in doubt, you throw it out. That's called No on 66.

Signal: Of all the things on the ballot — there's a presidential election going on; I'd almost expect to see you out there stumping for John Kerry.

Brown: Well, I've done that, too.

Signal: But why 66 over everything else? And why haven't we heard very much about 66? We've heard more about the casinos and stem cell research than we've heard about 66.

Brown: You have. More money is being spent on that. Well, for one thing, up until very recently, the prosecutors haven't had a lot of money. So you haven't heard that much about it. A lot of the these other things — in the stem cell (measure) you have a whole industry that's going to make billions of dollars out of this, so they can take a little bit of the money they're going to probably get out of the initiative and spend it to get it. That's why you hear that. If you're talking about the casinos, lots of big money on that, and Arnold himself is fighting it. If you're talking about Kerry and Bush, you're talking about $1 billion in spending; that's why you hear about that.

The reason I'm on (Proposition 66) is, first of all, I was asked to by my own district attorney, my own police chief, people I know and respect, and then when I really got into this thing — because three months ago I didn't fully understand the implications here — I decided to throw myself into it.

Signal: Did you support the three-strikes initiative, Proposition 184, in 1994?

Brown: You know, I think I did, but you know, I don't know what I did in 1994. I'm not sure I did.

When I was governor — a lot of people don't know this — I signed the "use a gun, go to prison" bill. Up till the time I was governor, there were no mandatory sentences. We put in mandatory sentences for assaulting the elderly, the selling of hard narcotics. We also increased the sentencing for burglary. We increased all the sentences. And at the end of my eight years, the increase of convicted felons going to prison instead of probation or jail was an increase of 50 percent.

I also signed the bill funding career criminal prosecution. I set up the Crime Reduction Task Force. And that's why, in my reelection, I was supported by most of the district attorneys — San Diego, Alameda, San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Signal: The California Democratic Party, which you once chaired, is —

Brown: Is more liberal than the Republican Party. That's true.

Signal: The California Democratic Party favors Proposition 66. Why aren't you with them?

Brown: There's a Democratic district attorney of Napa and a Democratic district attorney of San Francisco County, Kamala Harris. Both of those Democratic attorneys are against this, too. Where I first learned about this was from a district attorney, a deputy, in Alameda County, who is also a Democrat. So, yeah, the party position, and other liberal groups, are opposed to this, because they want prison reform, but I doubt whether they've really looked into this. Some of their constituents push them this direction. And I think more thoughtful people in the party — certainly would want prison reform. There's always a need. And it's by no means perfect, the way the sentencing structure works. But this is not the way to do it.

It is a wholesale release, as opposed to a return in some way, with a lot of conditions — the indeterminacy that would allow a parole board to say, "OK, you got a life sentence? We look at you. We think you're ready and the public is protected. We're going to let you out."

This doesn't do this. There's no parole board decision here. It's just, you're out. And that I think is mindless. It's automatic. And it's the automaticity of this that makes it so unacceptable. There's not a human being at the other end saying, "Wait a minute. A D.A. put this guy away for life. Let me revisit that. Let me really thing about it." No. This changes laws.

Burglary — if no one was in the house, then it's not a strike, then you get to go home. But what if you're an ax killer and they just happen to get you burglarizing a house when no one was in there? What if you're a child molester? What if you've had three or four or 10 rapes? You still get out. So, it's the automaticity and the mechanical quality as opposed to a thoughtful review by a panel of people on a parole board. That would have been the way to remedy injustices. This is just, "Hey, kitty by the door, let him out."

Signal: The Yes On 66 people say their ballot measure is way ahead in the polls. That indicates some widespread dissatisfaction with three strikes.

Brown: There is. What it is, is, I think, if people hear about someone and it's not a heavy crime, and they get a life sentence. What has to be understood is, the district attorneys — who have discretion — are only giving the third strike to about 400 individuals a year. And that's not just because of the crime, but because of the criminal. And that was the old idea of the indeterminate sentence.

In your first crime, you could get a five-to-life (sentence), and then you wouldn't get a (parole) date until a certain period of time in prison, and when you showed yourself ready, they would then give you a parole hearing, and then if you had a plan, a sponsor and a job, they'd let you out. That was a system that focused more on the criminal, not on the crime. Because you can have one person who burglarizes, and maybe that's all he did, and he has a lot of other circumstances, that's one thing. Then you have another person (who) commits the same burglary and they've done horrible crimes. So the three-strike process is very much a compensation because under the indeterminate sentence, many more people got out of prison, but those who are really bad were kept in a long, long time, maybe 25 to life. And even if they got out, they were reeled right back in for a life sentence.

When the state created the determinate sentence, that put a cap on how long people could stay in prison. And because of that, certain people were getting out way too soon, and under the old indeterminate sentence, they would have had life sentences and they wouldn't have gotten the early dates and they would have been kept in there a long time.

When that earlier scheme was eliminated, they brought back three strikes. And that's an effort to deal with something that happens to be a painful but deep truth. There are certain people who just can't live on the outside in the free world without causing real havoc. Those are the individuals that are the object of three strikes.

Now, have there been mistakes made? I'm sure there have been mistakes made. And there could be a process — and not just among three strikes. That's true of anything in life. I mean, people aren't perfect. We're only human. And there are ways to get at that. People can file appeals, they can do habeas corpus, they can appeal to the governor for a commutation. And if they really wanted to, there could be a commission process to look into the criminal justice system. Which, by the way, we've been looking into for as long as I can remember, under my father, under myself, Deukmejian, Davis, and now. You're always looking at the system. Because no matter how you put it together, you're never quite satisfied. That's just the nature of crime and incarceration.

Signal: Let's switch subjects. You have some experience with presidential campaigns. A lot of people still seem to be undecided. What do you tell people who can't bring themselves to vote for either Bush or Kerry?

Brown: First, I find it rather — I don't want to say "odd," but if you can't make up your mind now, with all the events and all the information, that's a very interesting state of mind to be in.

But if you're in that state of mind, I think — I guess the first point you have to look at is that Bush took us into the war in Iraq, and that war — if you don't like it, you say, this is a big mess, it's a quagmire, it's cost a quarter of a trillion and there's no end in sight. And this guy didn't really tell the truth about the weapons of mass destruction, and besides that, it was managed very poorly. You vote for Kerry if you think that.

On the other hand, if you think (Saddam) was a dictator and that thing could fall apart anyway, it's a rotten mafia, and if that fell apart then you might have Saudi Arabia falling apart and the whole Middle East could blow up and that George Bush made a bold move to go in and stabilize it by throwing out the dictator and giving the people who are oppressed a chance at a better life — if you believe that, then you vote for the president.

There's one other point which I think will give you pause about both candidates. Both of them are seemingly complacent with a $400 billion deficit that over the next 10 years, is going to be $4 trillion to $5 trillion. It was only four years ago that people were talking about a $4 trillion surplus. Now we're talking about a $4 trillion to $5 trillion deficit.

On top of that, we're not even counting what I'm going to tell you next. There's a $50 trillion — trillion as in T — gap between what we are obligated to pay under Medicare, under Social Security, under pensions, and what the current tax system will generate.

Now, neither Kerry nor Bush is dealing with that. There's one reason: Social Security is what we call the third rail. You touch it, you're electrocuted politically. But it is important that we know about that.

So I think — and by the way, there are some differences. Kerry is stronger on the environment; I think he is more concerned about working-class people; that's true. Bush, on the other hand, is more pro-business; he's had those sweet tax cuts. I think they favor the rich too much, and I think they're too big. Basically, it's a rather odd thing that you declare war and then you have a massive tax cut. Normally, when you go to war, you've got to raise more money. So we've spent a quarter of a trillion more, but we've lowered the taxes. I think there's a little bit of hocus-pocus. Not a little bit; a lot.

But again, the country is very divided. And I think it's based on two different views of that war in Iraq. And then there's the usual loyalties of the Democrats, the unions, the working-class people; the Republicans, independent business, big business and that. So there you have it.

It's a very interesting election. I've never seen so much feeling about it. There (are) people who are going to Iowa, they're going to Florida. There's a lot of anti-Bush feeling.

I know in this part of the world, we're in Bush country, I think, in this particular (area) right here (Santa Clarita), but I can make a report that from the Bay Area — well, in the Bay Area, Arnold only got about 38 percent on the recall; here (Santa Clarita) he got 75 (or) 80 percent. So we're a very divided country now, and what I'm most worried about, with the Supreme Court, with the extension of American power, and all these places, I think we're going to have more attention and more discord as we go down, and what we really need is people to bring us together, work out some compromises, and find the common ground that can bring Americans together. I think that's the most important challenge for whomever wins this election.

Signal: Proposition 1A would guarantee cities and counties their funding. You've seen it from both sides: In the governor's mansion — or, rather, the governor's house —

Brown: I lived in an apartment. I didn't live in the governor's mansion. We don't have one of those.

Signal: No offense intended. In your governor's apartment. Should the governor and Legislature have the freedom to set tax policy? Or, as mayor of Oakland, are you with the other cities and counties in support of 1A?

Brown: Yeah, I'm on 1A. Arnold is there; the 10 mayors of the big cities are for it.

Here's the deal. Before Proposition 13, the property tax funded city and county government and special districts. That gave you a predictable stream of money with which to provide your local services: police, fire, pothole repair and all the rest of it. Then, when the state started taking over all this, because we put a cap on property taxes — they were reduced two-thirds, and it's 1 percent, growing 2 percent a year — there wasn't the money. So the state provides the money. But the state provides it, and then when it gets in trouble, it grabs it back. But you can't fire policemen, you can't close libraries, you can't turn off your streetlights —

Signal: Not and survive as mayor.

Brown: No. But it's still not right. We're in the front lines. We're there with fire, police, basic stuff that we've got to do. And ( Proposition 1A) is a guarantee. But like everything, by a two-thirds vote you can still take it away.

So, it's a good, predictable commitment that the governor is for, the 10 mayors are for, I'm for. I think it's reasonable. And if those folks in Sacramento run into trouble, and they don't have enough money, then they ought to deal with it.

And by the way. Just like the federal government, the state government is in the hole $15 billion to $20 billion. And that is the big challenge for the governor. What do we do about it? I'm kind of happy I'm not governor right now.

Signal: Do you think Arnold has been doing a good job this past year?

Brown: A very good job.

Signal: We'll be seeing you on the ballot for attorney general in two years —

Brown: I'm not announcing, but there's a good — if everything goes right, I want to come back here and tell my story.

See this interview in its entirety today at 8:30 a.m., and watch for another "Newsmaker of the Week" on Wednesday at 9:30 p.m. on SCVTV Channel 20, available to Comcast and Time Warner Cable subscribers throughout the Santa Clarita Valley.

©2004 SCVTV.

|

|

|