|

|

|

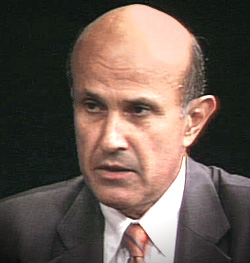

SCV NEWSMAKER OF THE WEEK:

Sheriff Leroy D. Baca

Interview by Leon Worden

Signal City Editor

Sunday, November 9, 2003

(Television interview conducted Oct. 27, 2003)

"Newsmaker of the Week" is presented by the SCV Press Club and Comcast, and hosted by Signal City Editor Leon Worden. The half-hour program premieres every Wednesday at 9:30 p.m. on SCVTV Channel 20, repeating Sundays at 8:30 a.m.

"Newsmaker of the Week" is presented by the SCV Press Club and Comcast, and hosted by Signal City Editor Leon Worden. The half-hour program premieres every Wednesday at 9:30 p.m. on SCVTV Channel 20, repeating Sundays at 8:30 a.m.

This week's newsmaker is Los Angeles County Sheriff Leroy D. Baca. Questions are paraphrased and some answers are abbreviated for length.

Signal: Countywide, in mid-October, you've been dealing with the blue flu. What are the issues there?

Baca: The issues are focused on primarily the fact that since January, the deputy sheriffs have not had a contract ... meaning it expired. Therefore the deputies feel that this contract issue is vital to what they do as deputy sheriffs: that they work hard, and that they do the things that all of us hope that they would do, and more; they are very innovative, they work diligently in the jails, in the courts, in the patrol environment, the detectives, and they feel that they're being ignored and they're frustrated and they want to let the world know that they need a contract.

Signal: Why haven't they had one?

Baca: No money. This is a really tough time. The Sheriff's Department has lost $166 million, 926 less deputies, 200 less professional staff. The county has found itself at a place where it's very difficult to generate a future based on any increases, and therefore we're suffering the consequences of a bad economy.

Signal: Why does the budget problem prevent there being a contract with the deputies?

Baca: I'm not a part of the negotiations; you know, it's (the) county versus (the) labor organization that represents the interest of the deputies. But I am, as you know, a spectator, watching all the details as they emerge.

The difficulty is that the contract itself is vital to ensuring that no benefits are lost, that individuals are seeking an increase — and the message that I hear (is) they would like 3 percent, 3 percent, 3 percent over the next three years, as what the LAPD has — and so it gives us some frustration ... Why was the city of Los Angeles able to acquire a total of a 9-percent (increase) over three years, and the L.A. County Sheriffs who are here, that's their counterpart, are not able to? And I think that's part of the frustration.

Signal: Has the sick-out been organized by the rank-and-file deputies' union, the Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs?

Baca: We don't know, and I think that I'll have to accept that the leaders of the union say that they're not leading this particular activity, and I'll take them on face value. I don't know the answer to the question. But the fact of the matter is that you can't have over 600 or 700 people over a planned period time go out on one of these blue flus and not have some leadership involved in this.

Now, just who they are remains to be seen, but this is definitely a labor action, this is definitely what you call a strike, this is definitely a way to disrupt the service of the county of Los Angeles in an area that should not be disrupted.

Signal: It's technically illegal for deputies to go on strike, right?

Baca: It is, and I think the deputies understand that. My concern is that they do an outstanding job; do they deserve what they're asking for? Yes. Is there a thing where they have proven over and over and over again to be the top performers in a variety of areas — jails, patrol stations, investigations and the court system? We have the largest of everything to take care of: More prisoners are in the county jails than any other place in the United States. We have more courts than any other place in the United States. We have a diverse public safety responsibility with 40 contract cities, nine community colleges, the entire Metropolitan Transportation Authority, and we therefore are a can-do organization. So I have no quarrel with the deputies' frustrations or needs. I just have a big quarrel with, do you put public safety at risk because you have a beef going on relative to your contract?

Signal: And now you have convinced a court to issue an injunction against certain deputies who had gone out on this blue flu.

Baca: Yes. What has happened is, the county counsel went to court seeking a temporary injunction against this blue flu activity. We purposefully and specifically served every deputy sheriff with the court order, and at that point the rules of the game changed. Because now it's no longer, you're violating county policy; now you're violating a court order. And I think that as of this conversation you and I are having, this blue flu has now come to a close.

Signal: What are the answers to the budget problems? Will you be looking to Arnold Schwarzenegger for the answer?

Baca: The problem of how we got to this mess to begin with can easily be described by, one, a poor economy, but two, poor money management coming out of Sacramento. In other words, Santa Clarita and any other city in California requires that there be a reliable relationship with Sacramento when it comes to the money that Sacramento apportions to cities or counties. That money happens to come from the vehicle license fee. We know the governor says he's going to roll back the increases. In the past, that vehicle license fee, when it was rolled back ... the loss was offset by the extra money that Sacramento had. Now that they don't have extra money, they've deferred a certain percent of that money coming back to the cities.

So what do we have, in effect? We have Sacramento basically balancing its budget on the back of counties and cities. And I object to that. I think that if the governor wants to roll it back to a level that is more tolerable by the vehicle owners, fine, but you better find some commensurate money to give to the cities and counties so that the cities and counties don't lose more deputy sheriffs, more police officers, more quality of life issues.

I have a huge bone to pick with how we, as the taxpayers, have let Sacramento and legislators, who are well meaning in what they do — I don't think that there is a bad person up in the Legislature — they just aren't good money mangers. And when bipartisan bickering goes on, the first thing our governor needs to do is to close the gap between the Republicans and Democrats, and let's get some common sense on the table so that one, quality of life issues are not eroded because of Sacramento's mismanagement of dollars; and quality of life will never happen without good public safety. That means Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department, that means LAPD, that means all the police departments. That should be a top priority, and we keep getting shuffled into the area of secondary and third-level priority. That's wrong. And that's why I'm fighting for a bigger discussion on changing the tax structure. Income tax — how much of my income tax and your income tax ... comes back to the city of Santa Clarita or the county of Los Angeles? We don't know. It's spent on a lot of different programs, but at the same time, where's the quality of life improvement? And that's where I'm coming from. I'm saying, California is nothing more than 58 counties and 350-plus cities. We all live in a city or county. We happen to also live in the state of California. But local city councils, local boards of supervisors — they all balance the budget. Sacramento hasn't learned how to do that yet.

Signal: Assuming the car tax is rolled back and there's a net zero coming out of Sacramento, are there are things that could be done within the county in terms of the way money is allocated? Is the Sheriff's Department getting a big enough slice of the county's pie?

Baca: Interestingly enough, the answer to that question is, probably not. But at the same time, what is the state of affairs with the county's finances? The county has a $16 billion budget. All but about $1.25 billion is mandated funds, so what I have to do is share (in) the discretionary dollars that are left, which is $1.25 billion. Do I think I deserve more? Absolutely. But somehow, that amount of money for an entire county that has health-care problems with its deficits, public welfare with its problems, Children's and Family Xervices gaps, with their problems, and then ultimately the infrastructure of roads and the like and flood control districts and so forth, we have a county that literally has been underfunded historically since 1978 when Prop. 13 was authorized by the voters.

Ironically, back then ... the state sales tax was 4.25 cents. Now it's 8.25. The question is, where is all this increased revenue being spent? And I say, fine. Education is a very important part. At the same time, so is public safety. And so I'm saying that the competing interests have, in effect, confounded our legislators in Sacramento and somewhat confounded our voters. We've tried to get more into education with Prop. 98, but we really need to not erode public safety, because in certain parts of California, kids are going to school afraid; they're getting attacked — in school, after school; we have a huge gang problem in parts of our state. All these factors erode educational quality, and we also know that there is an issue with non-English-speaking kids vis-ý-vis English-speaking kids, and I'm not convinced that pouring endless amounts of money into education is going to raise the quality of life of the kids that are going to these various schools.

I think that there's a time now that we have to look at what the practical aspects are of our educational system. And since I've taught part-time throughout my entire career in various levels of schools, junior high school and high school, I have a little something to say about our lack of support for teachers and what they're faced with now these days. They're being asked to do much more than just teach.

Signal: Does the county need more deputies than you're able to hire?

Baca: I need 10,000 deputy sheriffs (total). That's the bottom line. And that's the top line. ... Right now I have about 8,200 deputy sheriffs. And we're going down. We've lost 900, and if this trend continues as we're being told under our forecasting of the budget, we will end up with 1,500 less deputy sheriffs. This is unconscionable. It is shameful.

My theory on this? Let's get to the voters again. Let's get to the voters and say, hey, our state income tax, we want 25 percent of it sent to counties and cities. That's where we live. Now the state's going to say, we can't do that. We're going to have to reduce education, we're going to have to reduce health care, we're going to have to reduce this, we're going to have to reduce that. I'm saying, wait a minute. How come it is we can find ways to attack a $38 billion deficit, and how come it is we can talk about recalling a governor, but we cant seem to figure out that maybe we spent too much money on a lot of other things? But I can guarantee you one thing: They have not spent too much money on public safety.

Signal: The California League of Cities is looking to qualify a measure for the November 2004 ballot to stop the state from raiding the coffers of city and county governments. I assume you're in favor of that.

Baca: Absolutely. The battle line has got to be drawn. California — let's talk about the Coastal Commission and the millions of dollars that go into the Coastal Conservancy Commission. That's another one. There's two of them. How many counties have coastlines? Not all 58 counties have coastlines. The counties themselves, under an umbrella policy by the state, can say, form your own coastal commissions and manage what is going on in your coasts and therefore do what is right. But why do you have the whole state bureaucracy that supports this effort in Sacramento? It should be county by county by county.

Signal: The city of Santa Clarita contracts with the Sheriff's Department for police services within the city. The City Council can decide to allocate a greater portion of its money toward personnel, and this year they're paying for a new deputy while 900 are being cut elsewhere in the county. Are we going to end up in a situation where the unincorporated county territories of the SCV, like Castaic and Stevenson Ranch, will be understaffed in comparison to inside city limits?

Baca: Yes. I think that that's a very distinct possibility.

Signal: How do we overcome that?

Baca: By funding the L.A. County Sheriff's Department the right way. And when I say the right way, in 1992 and 1993, when we were starting to enter that recession era of the mid-'90s, the L.A. County Sheriff's Department had $750 million of county general fund money. When I took office, that amount was about $600 million, and that's five years ago. The gap between what was, and what is today, is still there today. In other words, the county, for whatever reasons, has been unable to sustain the general fund contribution to the county Sheriff's Department at the level it did 10 years ago. I have a concern with that.

The half-cent sales tax that Prop. 172 provides us, gives us some matching dollars. That allows the county to have some flexibility with its general fund money. I'm asking, and I've asked, for an audit, and the concluding point now as to what the financial stability of the Sheriff's Department is and what are the patterns that has caused it to be somewhat unstable at times. And therefore we need to find a better answer here, that the taxpayers should have more involvement in the process. And it's interesting — there is a mechanism where they can go before the board and discuss their priority feelings, and they can also make recommendations to the board. But the board, again, as I said, the whole county has shrunk its flexibility base with taxpayer dollars, and therefore there aren't enough (dollars) to do the mandates that the county has.

Signal: We're a relatively affluent part of Los Angeles County. If the city of Santa Clarita can afford to add police personnel, would it be in the interest of the unincorporated areas of the Santa Clarita Valley to annex into the city of Santa Clarita?

Baca: In my opinion, yes. It's certainly a more stable form of taxation.

Now, the county area of Hacienda Heights recently had an option to incorporate, and they chose not to. So there's a political dynamic that is there that you can't necessarily guide through some levels of, "It's better for you because your financial stability will be ensured. It's not a guarantee to the voters. The voters get apprehensive. But I do think that as the county grows, in terms of its population base, that the county unincorporated areas will be considering whether or not to incorporate.

Signal: Switching gears: Deputy David March. He lived in Saugus. He was making what should have been a routine traffic stop in Irwindale in April 2002. He was gunned down. The suspect is Armando "Chato" Garcia. He is believed to have fled to his native Mexico within about 24 hours after the murder. Mexico won't extradite in a death case. Over the summer you met with Mexican Pres. Vicente Fox, or with his people?

Deputy David March

Deputy David March

Armando Garcia

Armando Garcia

|

|

Baca: I didn't meet with Vicente Fox. I met with the heads of the (Mexican) federal attorney general's office over the issue — the Mexican equivalent of their federal police. But they are prosecutors, they're attorneys, they're not cops in the context of how we see things. But they run the system of extraditions; they run the systems of ministry of foreign affairs issues concerning prosecutions in Mexico for fleeing Mexicans from America or any other place.

Signal: What happened?

Baca: A lot of things happened. First of all, I took a team from the attorney general's office of California with me; I took my own investigators and captain of my homicide bureau; and I took a member of he legal staff of the county counsel. I asked to visit a prison, and I asked for dialogue on the articles of law in Mexico that allow them to extradite, and what are the impasses, and what are they doing to change their laws to facilitate the return of an Armando Garcia.

They were very open, and I first of all went to the prison where, if a person who cannot be extradited, say a murderer — we have a death penalty, Mexico does not; therefore Mexico won't extradite based on a death penalty issue. Recently they changed their law, and I believe the Mexican authorities are correct when they say they're not happy with the new law that says you cannot also extradite if the person will be in prison without the possibility of parole. Which is what our system is, essentially, in California.

What I asked is, what are you doing to fix that second law that becomes so impermissible? And they said, we have an appeal to our own supreme court, and we are asking the supreme court to vacate that ruling that you can't extradite someone without the possibility of parole.

Signal: Do you know when that is supposed to come before the court?

Baca: They're going to get that thing resolved — they'll hear from their supreme court probably later on this year or early next. So the (Mexican) attorney general is actually fighting that law within their own country. So that's a positive.

The prison I visited had an individual who killed two Lynwood High School girls. One was his estranged girlfriend who, when she said, "I no longer want to see you," he, the next day, shot and killed her on her way to school, with her cousin. He fled down to Mexico like Armando Garcia. He was serving time in the Mexican prison that I visited. He had a 75-year sentence. Sixty years must be served, then you're eligible for parole. The guy is about 25 or 26 years old. Well, he'll be 86 years old by the time he's going to get released under their system.

Now, I have a desire to look at it from both angles. If we can't put a person into the death penalty here in the United States because they're down there in Mexico and we'll never get them up here, then the question has to be asked, why don't we prosecute them down there and have them sentenced to their own penal system?

I wanted to see what the penal system was like, because I get these messages that they've got some kind of a country-club atmosphere and that they're coddling their sentenced prisoners. I didn't see any country club down there. In fact, they have a jail that (is rated for) 2,000 people ... and they've got 4,000 people in it. Inmates have to share their cells. They have a whole different approach, but there isn't any patsy-type serving time down there that I witnessed.

At the same time, even with saying that, my belief is this: In California, we have 40,000 illegal immigrants serving time in California prisons. These are illegals that have come here, committed serious crimes, and they're serving time. Including many murderers. Now, if we look at this from a dollars-and-cents point of view, we say, well listen: It's costing us about $36,000 a year for one of these guys that's here illegally, serving time in state prison. At the same time, back in their own nation, if they're going to serve 60 years on a life sentence with the possibility of parole, it's better for them to pay for the keep of the inmate.

It costs, on a life sentence here in the United States, over the lifetime of the person, it's costing millions of dollars. Well, take that 40,000 that are constantly in California's prisons. We, right there, have a situation of unwarranted millions of dollars of what we must pay for people who shouldn't have been here in the first place.

Whose fault is this? The federal government. The federal government should pay for every cost that this county has endured relative to illegal immigrants in our county jails and our state prison system. And we're still getting no straight answer out of Washington.

Signal: Are you making that plea?

Baca: Absolutely. I go to Washington with the Board of Supervisors, and part of my visit to Mexico was because Supervisor (Michael D.) Antonovich, who represents this area, is strong on this issue, and my thing is to get the two countries to come to some point were American interests are not subverted by Mexican interests, and at the same time, if you want any sweetheart deals about what the border is all about, that you've got to resolve this problem with illegal immigrants committing crime, first. That there's got to be some acknowledgment here that we in California cannot afford to pick up the tab for 40,000 criminals in a jail system, and that Mexico has no interest in this issue at all — at the same time that Washington kind of plays with the issue and cuts back money that would ordinarily come to the county or the state to offset the costs.

Every nickel should be paid by the federal government, because they're the ones responsible for the border controls, they're the ones that are responsible for the policies between the two nations, and the treaty, and they therefore have the obligation to relieve this county and relieve me as the sheriff of having to cut back resources and other parts of my public safety obligations just because I don't have enough money for the 20 to 23 percent of illegals that are in the county jails right now.

Signal: Based on what you saw at the Mexican prison, would you be satisfied seeing Armando Garcia prosecuted in Mexico?

Baca: If he got a 60-year sentence without the possibility of parole, until that point — even with the possibility of parole at that point — I don't think that that's an unreasonable place for him to be. I think that the death of David March is the tragedy here. David March is not coming back, under any circumstance. But we have (widow) Teri March, who lives here in Santa Clarita; we have (parents) Barbara and John March, who are very much a part of this; we have Erin, his sister; and we have his brother-in-law, who is a district attorney investigator. They are the ones who have more at stake with where he serves his time than even I do. And my heart goes out to them. And it goes out to the people who are supportive of wanting justice. But we're not going to have justice unless we try and change some rules, and we also have to open up our minds to the fact that if a guy commits, a person, a suspect like Armando Garcia, commits a murder, that he must be brought to justice. To let him float around in space is not good.

Signal: Is he floating around in space, or does the Mexican government know where he is?

Baca: The Mexican government once knew where he was. And when I was down there —

Signal: You mean once, after April 2002?

Baca: That's right. Because the case was rather new and it was fresh, and what they say in return is that they cannot take enforcement action unless some policing or district attorney or attorney general's office, some legitimate wing of law enforcement, gives them the documents indicating that this is a fugitive that they're seeking.

Signal: OK, but they did know where he was, and now they don't?

Baca: They don't know where he is now.

Signal: Did they lose track of him, or are they lying?

Baca: No. They lost track of him. Primarily because they were expecting the filing of the information through the State Department, which is the procedure, to get into their hands, and at that point they would have arrested him.

Signal: Is there any reason to believe he has returned to the United States? He certainly has been back and forth enough times.

Baca: He, in my judgment, will never get back to the United States unless he is extradited. Because the motive for him to get back here is virtually nonexistent. So he, in effect, is having, as Teri March says, his piña coladas at some beachhead, for all we know.

But you see, the thing that's difficult with this is that the Mexican police and the prosecutors who run the system are not happy with where they are with this. They don't want murderers running around, even in their country. They want them under wraps, they want them arrested, and we have to make some tough decisions as to, where do we go with this? Bring him back or prosecute him there?

See this interview in its entirety today at 8:30 a.m. and watch for another "Newsmaker of the Week" on Wednesday at 9:30 p.m. on SCVTV Channel 20, available to Comcast and Time Warner Cable subscribers throughout the Santa Clarita Valley.

©2003 SCVTV.

|

|

|