|

|

|

Proximate Cause: Pilot Recalls 'Twilight Zone Movie' Tragedy.

By Leon Worden SCVHistory.com | July 23, 2013 | ||||||

|

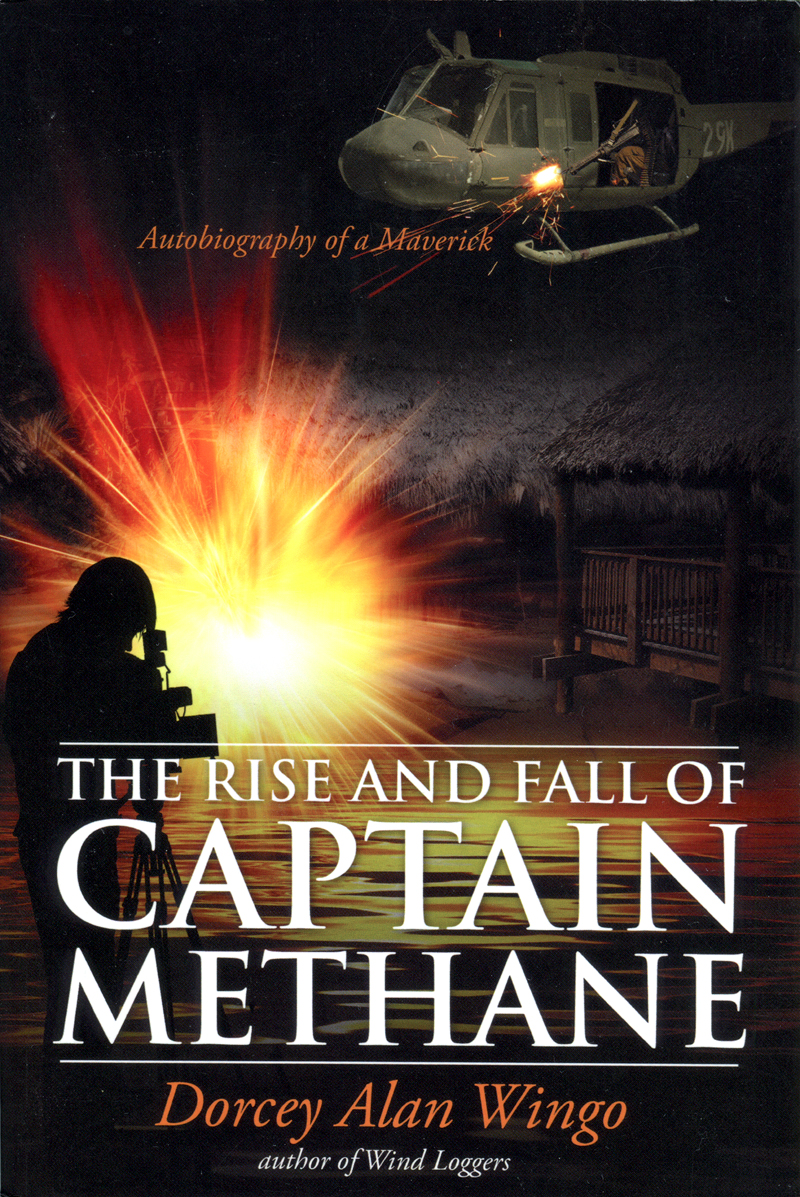

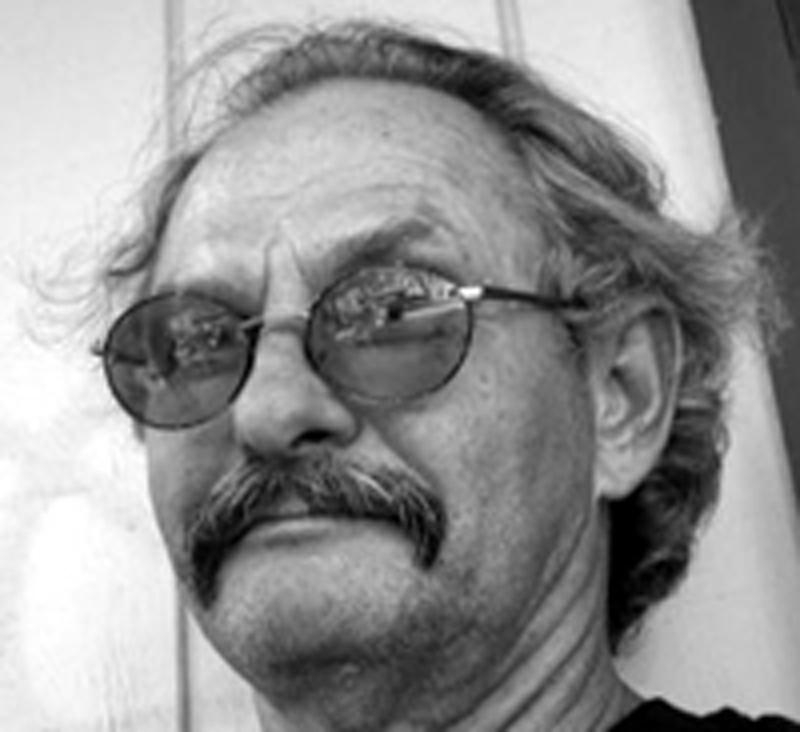

You want to believe he does. You want to find an expression of remorse in a story such as this. It helps to bring closure. "(W)hen things go horribly wrong and your flying machine cuts down three people on camera, there's no making it go away," Wingo writes. "It never goes away. And if you let it get to you, it will drive you insane." But is "never going away" the same as remorse? Remorse requires a sense of responsibility, even guilt, and those sentiments are plainly absent from Wingo's self-published 2010 book, "The Rise and Fall of Captain Methane: Autobiography of a Maverick." The closest he comes to self-criticism is a fleeting and shallow admonishment for being too trusting of others. The take-away is that this man — who earned his nickname as a youngster for his proficiency at farting on command — believes he was caught up in a horrific series of events that were beyond his control. It's a difficult read, more so when the reader is an editor who would, in any other circumstance, set aside the text for its distracting use of italics, boldface and exclamation points! But these are important, first-person facts — things that must never be confused with truths — which belong in the Santa Clarita Valley's historical record, to be taken for what they are, no more and no less. The bigger distractions, during any attempt to review Wingo's experiences of those dark moments, are his many resentments, which have festered for three decades. Resentment of a feisty, theatrical and ultimately ineffective prosecutor. Resentment of the media circus. Resentment of a top Hollywood helicopter pilot who got Wingo movie jobs and then betrayed him by testifying against him. Resentment of a court process that derailed his life for six years. The reader needs hip-waders to get through it all. As I write this, it's the 31st anniversary of what many still consider the worst on-set tragedy in Hollywood history. It was approximately 2:20 a.m. on July 23, 1982, when Dorcey Alan Wingo's olive-drab UH-1B Huey helicopter fell out of the sky at Indian Dunes in Valencia, decapitating actor Vic Morrow and one of two Vietnamese immigrant children with its rotor blades while crushing the other to death. * * * "As I guided the Huey into position for the final shot, veteran actor Vic Morrow stood at my two o'clock, beyond the rotor's arc, with child actors Myca Dinh Le and Renee Chen clutched in his encircling arms. They were brightly illuminated by the ship's powerful NightSun spotlight, focused by Production Manager Dan Allingham from the helicopter's left front seat. "Three million candlepower lit up the trio with an eerie wobbling luminescence. Vic was straining, looking toward the river, and listening for our machine gun fire; his call to action. Two stuntmen in the rear of the Huey manned the M60s, waiting for us to echo the 'FIRE' cue. "I took up a bearing on a bamboo structure forty-five degrees to my right and down forty-five degrees, locking our prearranged position by keeping two focal points aligned. (Wingo's footnote: A technique sharpened from years of flying USFS Firefighter Rappel Teams into small clearings in tall timber.) "Director John Landis spoke calmly into the handheld portable VHF radio, 'Lower, lower, lower.' "I complied slowly, switching to alternative focal points in order to hold our position just off the shoreline. Then came Landis' call for action, 'Fire — Fire — Fire!' at which point our machine gunners opened up and all three explosions occurred along the cliff to our right, in the prescribed tempo: thousand-one, thousand-two, thousand-three. "As the fireballs heated up the night, Vic charged into the water with the children, moving north toward the opposite shoreline. Pulling a touch more power, I introduced left pedal, starting the rehearsed nose-left turn, and eased the cyclic forward. Dan followed Vic with the light. "It was then that special effects technician Jim Camomile, for reasons known only to himself and God, raked one electrified nail across several others that were wired to multiple gasoline firebombs intolerably close to the low-hovering helicopter, sending the chopper and one-hundred-odd moviemakers and onlookers into living hell. And three vibrant human beings to their shocking deaths." * * *

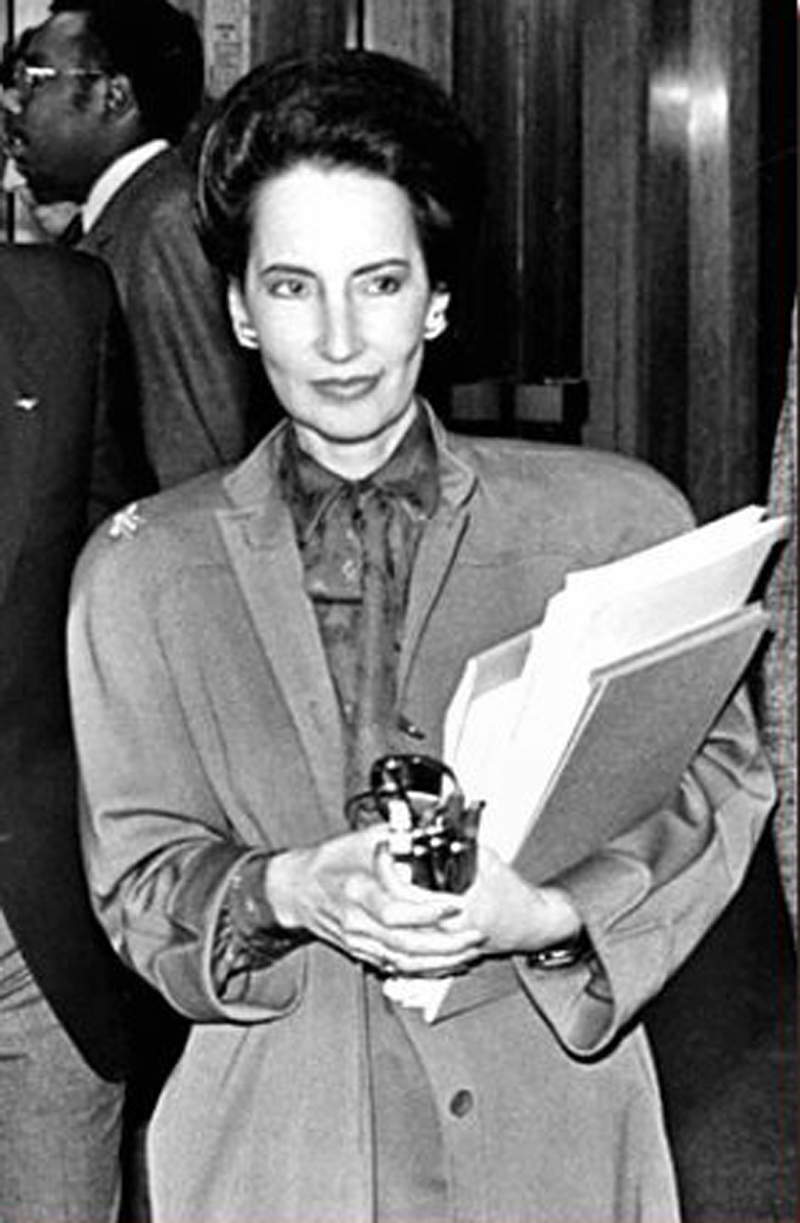

Dorcey Wingo took the fifth when called to testify before the grand jury. On June 15, 1983, Wingo, Landis and Allingham, together with Associate producer George Folsey Jr. and explosives specialist Paul Stewart, were charged with manslaughter. It would be another three years before the case came to trial in the L.A. courtroom of Judge Roger Boren, himself a Santa Clarita Valley resident. District Attorney Robert Philibosian, who would lose his seat to Ira Reiner in 1984, assigned the case to prosecutor Lea Purwin D'Agostino. She had earned her reputation as the fearless "Dragon Lady" when she served as co-counsel on the Alphabet Bomber case. The deadly arsonist, Muharem Kurbegovic, gave her the nickname and it stuck. In his book, Wingo fixates on the trademark golden queen-bee brooch she always wore on her suits. "The trial began on September 3rd (1986)," he writes, "and it became clear that prosecutor D'Agostino was going to play to the cameras as if she was [sic] up for an Oscar. The silly 'Queen Bee' pendants that she blatantly exhibited on one shoulder with each and every costume was [sic] a reminder to me that not all was right with the little woman who used to work in a Hollywood studio office. "I drew a cartoon of her scratching her beehive hairdo absentmindedly with a pencil — suddenly looking up, startled — then running away, shrieking in panic as the swarm of bees she disturbed pursues here. Landis liked that one!" D'Agostino proved — and the defense admitted — that Landis had hired the 6- and 7-year-old child actors in violation of California law, which prohibits child actors from working at night or in proximity to pyrotechnics. Evidence was presented to show that Landis paid them under the table to skirt child-labor laws. The crux of the case centered on whether Landis was reckless in ordering the helicopter to move "lower, lower, lower" to achieve a more spectacular effect. To that end, D'Agostino argued that Landis knowingly hired a helicopter pilot with little on-camera experience, the implication being that a more experienced movie pilot would have had a better handle on the situation and would have disobeyed the director's orders. In his book, Wingo naturally takes umbrage. He'd been flying Hueys and similar aircraft since the late 1960s when he was an Army combat pilot in Vietnam. He flew them while servicing oil rigs in remote mountaintop regions of Peru, and he had done some movie flying in the 1970s. Not a lot, but some. By 1982, Wingo was director of operations for Rialto-based Western Helicopters Inc., which supplied the aircraft and pilots and associated support personnel for the film. Illustrating the absurdity of the argument, in Wingo's mind, was D'Agostino's assertion that there was no operations manual in Wingo's Huey at the time of the crash. Yes, it's an FAA requirement, but is an experienced helicopter pilot going to pull it out and read it on set? In the end, Wingo was offered immunity for his testimony, but he didn't have much to say that could be used against D'Agostino's primary target, Landis. As Wingo relates in the book, the director and the pilot, and their wives, had become allies and socialized together for the duration. Wingo refers to "Director Landis" with reverence. * * * Wingo points fingers in many directions, but in terms of assigning blame for the tragedy he points chiefly, if only cursorily, to James Camomile, the pyrotechnician, and Jack Tice, a fire safety officer from the Los Angeles County Fire Department who was on scene as a monitor. Wingo doesn't explain it, so he must assume the reader knows how explosive devices are set off. Mortar shells are connected by wires to a large board, each ending in an exposed contact. The pyrotechnician closes the circuit by touching each contact, at the appropriate time, with a metal spike or "nail" that's connected to a power source, like a car battery. It's what happens when you flip a light switch. The circuit closes and the device goes boom. What you wouldn't want to do, if each "boom" is to occur at a certain interval, is — as Wingo puts it — "(rake) one electrified nail across several others that were wired to multiple gasoline firebombs." They'd all go off at once. "Although it happened over twenty-five years ago," he writes, "I recall the night with disturbing clarity. I can smell the heavy gasoline and adhesive cement vapors and feel the thump-thump-thump of the Huey's rotor blades. As the fourth and fifth explosions detonated, shock waves and rapidly expanding air lifted the ship up and rocked us to the left. Allingham exclaimed over the intercom, 'It's too much, let's get out of here!' "But simultaneously a wicked shudder-clunk traveled through the pedals to my boots, and I recall that the ship started spinning left. (Wingo's footnote: The helicopter actually spun to the right; experts later testified that other pilots had the same illusion with tail rotor failures.) "I saw only alternating fireballs and blackness, fireballs, blackness, the cyclic going wild between my legs. Suddenly I caught sight of a bush near the shoreline, the only reference point I had to work with. I struggled to keep the ship level and cushion our impact as she came down on her own at full power, hitting hard in a left bank. "Suspended in midair from the right-hand pilot's seat, I slapped at the ship's power switches, released my belts, and dropped down awkwardly toward Don Allingham, stepping on him in the process. Apologizing, I squatted down and beat out his overhead greenhouse window with my hands to create an exit.

"We were quickly pulled out through the jagged plastic hole into the frigid waters by frantic rescuers. Someone yelled at us to head for the shoreline. One last passenger was partially trapped by the shifting camera cases and ammo boxes; they almost had him free. "Illuminated by the flaming movie set behind us, firemen in hip-waders sprayed frantically with their hoses; the rubber cement-fueled flames were resisting the deluge. "Thrashing to the shore, I turned to see that the helicopter's turbine engine was still running! Wading back, I found the main fuel switch still on, and cursed my haste. I shut the engine off and returned to the north shoreline in shock, but unaware of the awful truth." Quiet fell in the darkness, and the frogs in the Santa Clara riverbed started croaking again. "An Asian woman" — presumably the children's mother — "was sobbing incoherently." Then: "'Where's Vic and the kids?' I asked Craig [Wooton, Western Helicopters' fuel truck driver], noticing Director Landis and a couple of his aides searching in the dark, swirling water, just downstream from the mast. Craig's eyes met mine with a painful expression and he said, 'They're gone Dorce. The blades got 'em.'" Wingo was transported to Henry Mayo Newhall Memorial Hospital in Valencia for treatment of his injuries, as were several others. * * *

Veteran helicopter pilot James W. Gavin, founder of the Motion Picture Pilots Association, testified that had it been him, he would have refused to fly that night. For reasons known only to the author, Wingo doesn't use Gavin's real name in the book. He uses a pseudonym. Perhaps Wingo doesn't know you can't libel the dead. Gavin died in 2005, five years prior to Wingo's publication. Gavin, who'd hired Wingo for movie jobs in the past, "strode into court with a pretty blonde at his side," Wingo writes. "It was clear to me that he was out to do me in." Gavin's expert-witness testimony "faulted me," Wingo writes, "among other things, for not rolling off the ship's throttle at the point of losing anti-torque control. And while it is the standard published procedure for the loss of anti-torque control in a hovering Huey, veteran Army combat pilots had long drilled into younger pilots like me to 'keep it flying' while you figured out the problem and dealt with the emergency." So if the instruction manual had been in the aircraft, Wingo wouldn't have done what it said? "In the chaos and confusion of the critical instant, blinded by explosions and spinning back into blackness, I never reached the point that I knew what was wrong with my machine. I fought for control of an out-of-control helicopter — with six souls on board — that was flying in and out of some very large, hot fireballs. Would rolling off the throttle have changed the outcome? Would the six of us in the Huey have been burned alive? A real possibility, and another ugly what-if." Wingo adds in a footnote: "I personally know of two pilots who lost anti-torque control in a hovering Huey and, after spinning a bit, were able to return to controlled flight — making a successful run-on landing several miles away." As for Camomile, a Simi Valley pyrotechnician whose movie credits range from 1980's "Heaven's Gate" to 2007's "Live Free or Die Hard" — with many similar titles in between — Wingo says little more. "With all the ducking and dodging, waffling and backpedaling in the testimonies of Special Effects Technician Jim Camomile and Fire Safety Officer Jack Tice, even the newspaper reporters seemed to notice," Wingo writes. "Camomile, who was at the switch on the fateful night, spent three long days on the stand. Squirming under the barrage of intense questioning by five defense attorneys [including the high-flying Harland Braun], his ordeal before the jury must have been tough — but thanks to the powers that be, he wasn't facing six years in prison. I am not compelled to reproduce or comment further on their lame responses." Except, that is, to criticize Tice for telling the media that Wingo flew erratically during the final take. "I personally ... wanted to hear (Tice) try to explain to the jury his damning statements to the press on July 28, 1982, that 'the helicopter came in too late, too low, and too slow,' and that I had flown 'a aigzag course,'" Wingo writes. "Was he making this crap up to try and take the heat off himself?" The Los Angeles County Fire Department provided six safety officers for the location filming. Defense attorneys attempted to show at trial that one or more of them believed the stunt "would put the helicopter on the ground" but failed to stop it. * * * On Oct. 30, 1984, the National Transportation Safety Board attributed the crash to a communication failure between Landis, the director, and Wingo, the pilot. It ruled: "The probable cause of the accident was the detonation of debris-laden high temperature special effects explosions too near a low flying helicopter leading to foreign object damage to one rotor blade and delamination due to heat to the other rotor blade, the separation of the helicopter's tail rotor assembly, and the uncontrolled descent of the helicopter. The proximity of the helicopter to the special effects explosions was due to the failure to establish direct communications and coordination between the pilot, who was in command of the helicopter operation, and the film director, who was in charge of the filming operation." D'Agostino failed to secure a conviction against any of the defendants and lost her bid to unseat Reiner in 1988. Landis went on to direct Eddie Murphy in "Coming to America" and "Beverly Hills Cop III," as well as various Michael Jackson vehicles. Everybody from producer Steven Spielberg — who wasn't on set and reportedly shunned Landis after the accident — to the landowner, The Newhall Land and Farming Co., was named in a wrongful death suit. At least some defendants, possibly all, settled out of court for an undisclosed amount.

Gavin testified at the NTSB hearing that Landis hired Western Helicopters because it was "cheap," that Wingo's communications set-up was "lousy," and that he would have "taken his helicopter and gone home." After some negotiating by Wingo's attorney, Eugene Trope, the NTSB agreed to suspend Wingo's pilot license for 30 days, and the FAA sent Wingo a letter expressing the hope, in the author's words, that he would "fly right from now on." Wingo spent the next two decades flying Hueys for the logging industry in the Northwestern U.S. and Alaska.

Further reading: Death on the Set of "Twilight Zone: The Movie" by Alan Pollack

©2013 SCVHistory.com |

SEE ALSO: • Indian Dunes

NTSB Report

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.