|

|

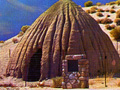

Cerro Gordo | Mojave Desert

Click image to enlarge

April 21, 2013 — Remnants of Victor Beaudry's smelter (furnace) on the west side of the Cerro Gordo mining camp. Beaudry's smelter ran 24/7, and while it might not have been quite as robust as Belshaw's smelter up the hill, part of Beaudry's smelter survives, while Belshaw's doesn't. Would Los Angeles have grown to prosperity in the 1870s and '80s — with multi-story buildings replacing low-slung adobes, and a ready market for farmers' surplus crops — if not for the riches of the Cerro Gordo mines? Angelenos of the day didn't think so. An estimated $17 million worth of silver and lead ore — $400 million in 2013 dollars — poured out of the Cerro Gordo mines in Inyo County. From the late 1860s to the late 1870s, it passed through the Santa Clarita Valley and Beale's Cut along a 200-plus-mile journey to the emerging pueblo. Teamsters driving 14 mules, on average, stopped at a dozen different watering holes along the way, including, as of 1873, the original Lang Station in Soledad Canyon. That was the year John Lang arrived and built a hotel just east of what is now the 14 Freeway at Shadow Pines. Three years later, the Southern Pacific would dedicate a rail depot at Lang's already popular rest stop. Teamsters had to be on the lookout for highwaymen like Tiburcio Vasquez and his lieutenant Cleovaro Chavez, who demanded what might politely be called tolls. With dozens of mule teams plying the route in both directions — to Los Angeles with ore; back to Cerro Gordo with fodder, liquor and sundries — teamsters sometimes managed to warn each other of bandit activity when their paths crossed. In those instances, it's said they would stash their ore along the road for later retrieval. The following is a short history of the richest silver and lead mines in California. Pablo Flores, a prospector who possibly hailed from Nicaragua and studied mineralogy at the Colegio de Minirio (est. 1793) in Mexico City[1], had been scouring the hills of California and Nevada for precious metals when, in 1865, he discovered silver and lead (which occurred together) on Buena Vista Peak in the Inyo Mountains, located between the Sierra Nevadas on the west and Death Valley on the east. Flores sent two companions to Virginia City, Nev., for provisions. Never seen again, they were presumably killed by Indians. Flores then went to Virginia City himself, told his friends what he'd found, and soon the area filled with Mexican and Anglo miners. Renamed Sierra Gordo[1] and then Cerro Gordo ("Fat Hill"), the peak sits eight miles east and 5,000 feet above Owens Lake. It became part of the Lone Pine Mining District, formed April 5, 1866, in response to the discovery. Another miner, Jose Ochoa, was pulling 1.5 tons of ore every 12 hours from the San Lucas Mine — one of an eventual 700 claims in the Cerro Gordo region — and hauling it by mule to a mill near Fort Independence, the Inyo County seat. That got the attention of a Quebec-born sutler at Fort Independence, Victor Beaudry, who opened a general store to serve the miners. Smelting ore in crude furnaces and using "vasos" (vessels) to refine it into a portable silver and lead mixture, the miners traded it for provisions at Beaudry's store. The brother of Los Angeles real estate tycoon and later L.A. mayor (1874-76) Prudence Beaudry, Victor Beaudry extended enough credit to enough miners that he was soon able to foreclose on their claims and gobble up most of the Cerro Gordo mines, including a half-interest in the largest, the Union, perched above the camp. In April 1868, mining engineer Mortimer Belshaw arrived from San Francisco. Instead of buying mines, he finagled a one-third interest in the mountain's largest galena lode (silver-bearing lead ore), which the Union and other mines were tapping. Belshaw and his partner, Abner B. Elder, took some smelted ore via San Pedro to San Francisco, where they organized the Union Mining Co. with a third partner and financial backer, Egbert Judson, president of the California Paper Co. Belshaw and Elder returned to Cerro Gordo, built an eight-mile toll road up the mountainside — the Yellow Grade Road (named for the yellowish shale), aka Cerro Gordo Road — and fired up a new, steam-powered smelter in September 1868 near the mountaintop, above the camp. Elder kept the furnace going 24/7 and produced 120 silver-and-lead ingots daily, each measuring 18 inches long and weighing about 85 pounds. At the same time, Beaudry was building a somewhat less efficient smelter on the west side of the camp. (A chimney from Beaudry's smelter still stands in 2013; Belshaw's doesn't.) Rather than compete, Belshaw and Beaudry threw in together and enjoyed total control over Cerro Gordo. Production increased to an average of seven tons a day and topped out at nine. The ore literally couldn't be hauled down the mountain fast enough. In December 1868, Belshaw and Beaudry hired another French Canadian, the famous freighter Remi Nadeau (1819-87), to haul the ore to Los Angeles. Thirty-two teams carted $50,000 worth of silver and lead — only half of the maximum output — down the Yellow Grade Road every day to start a three-week trek to Los Angeles where the silver and lead were separated at a proper refinery. In 1870, Beaudry started piping 1,300 gallons of water per day from the Inyo mountain springs (now Mexican Spring) to storage tanks at the camp. Also imported was borax from Death Valley, for use as a flux in the furnaces.[2] Nadeau's shipping contract expired in December 1871 and it went to James Brady who, in June 1872, built and launched an 85-foot steamer, the Bessie Brady, named for his daughter, to ferry ore from Swansea, the town he established on the east side of Owens Lake, to Cartago on the west side. This shaved a few dollars and a couple of days off of the transport. But torrential rains and other complications hampered freighting, and Brady couldn't properly perform on his contract. The ingots piled up. Plus, at this time, Brady and Belshaw were at odds over conflicting mining rights on the mountain (bound to happen when one man owns a mining claim and another purports to own the lode that the first man intends to mine). Brady won the argument in court but lost the shipping contract. Nadeau agreed in June 1873 to resume shipping, on condition that the two "bullion kings," Belshaw and Beaudry, would make him a full partner in the new Cerro Gordo Freighting Co. and spend $150,000 to build stations a day's ride apart — including one at John Lang's spread in Soledad Canyon. In 1874, the Southern Pacific Railroad pushed north as far as San Fernando, so after clattering through Beale's Cut on its southern journey, the ore traveled by train the rest of the way. (Lang connected to the rail line two years later.) Belshaw refurbished his furnaces which were now producing 400 ingots daily, double the 1871 rate. As many as 100 Nadeau teamsters driving 80 teams consisting of 14 mules and three high-sided wagons carried $700,000 worth of ore annually to Los Angeles and spent half that much, about $1,000 daily, on local farmers' entire surplus feed crops — 2,500 tons of barley and 3,000 tons of hay, or roughly 27 percent and 40 percent, respectively, of L.A. County's entire yield.[1] Cerro Gordo's population at this time tipped the scales at 4,500 — a mix of Anglo, Indian, Hispanic and Chinese workers, most living in bunkhouses and earning a top rate of $4 per day. The mining camp sported general stores, saloons, restaurants, at least two hotels (including the lavishly appointed American Hotel built in 1871 by Mr. and Mrs. John Simpson), two competing dance hall-brothels (one burned down mysteriously one night in March 1880, along with eight other buildings[1]), doctors', lawyers' and assay offices and blacksmiths — but no church, school or jail. Payday was followed by carousing at the saloons and brothels and often ended in gunfire; men sandbagged their bunks to insulate themselves against stray bullets.[2] Mines have an average life expectancy of about five years, and despite the feverish pace of production, Cerro Gordo's first boom lasted somewhat longer, and the mountain continued to produce on and off for decades. Major mining activity slowed after 1876, when Belshaw shut down his furnace. The Union works burned down in August 1877; they were repaired, but now the mine was in debt. Wages were cut to $3 a day and half of the miners left. The Union closed in October 1879 and a month later, Beaudry's furnace was shut. Nadeau hauled out the last 208 ingots and a 420-pound glob of silver on Nov. 21, 1879. Even the Bessie Brady was lost to fire in June 1882. By then the early "bullion kings" were gone. Beaudry left in 1876, splitting his time between his home in Montreal and brother Prudence's adopted home of Los Angeles, where Victor died in 1888. Belshaw moved in 1877 to the Northern California town of Antioch where he mined, among other things, and died in 1898. For his part, Nadeau invested his money in sugar beets, wine grapes, barley and land in downtown Los Angeles where, in 1886, he built the lavish, four-story Nadeau Hotel, the likes of which the pueblo had never seen. Today it's Times Mirror Square. Cerro Gordo wasn't finished. Small quantities, by comparison, of lower-grade silver ore continued to be extracted into the 20th Century. Then, in 1907, high-grade zinc ore was discovered at the 900- to 1,000-foot level in the Union Mine. A 200-ton reverberatory smelter was constructed at the base of the mountain east of Keeler and a cable tramway was strung above the Yellow Grade Road to carry the ore down in buckets. Results were mixed until 1911 when Louis D. Gordon got his hands on the operation. In 1914 he took title to the property from the previous owner, the Four Metals Co., and incorporated the Cerro Gordo Mines Co. Cerro Gordo was booming again. A 5.6-mile, gravity-powered Leschen and Sons wire-rope aerial tramway replaced the initial Montgomery tram and moved 20 tons of zinc ore daily to the railroad at Keeler. From there it went to the United States Smelting and Refining Co. in Utah for processing. Electricity and telephones arrived in 1916. Explorations continued for new silver and lead deposits. From 1911 to 1919, the reopened Union gave up 8,022 tons of lead and 720,000 ounces of silver. Starting around 1915, slag (waste material) from the old dumps was reprocessed. Old tunnels were extended and new tunnels were driven; one, the Estelle, about two miles below camp, started in 1908 and by 1923 had reached the impressive length of 8,100 feet, running straight through half of the upper Inyo mountain range. In all, 37 miles of tunnels snake through the mountain. Gordon eventually moved on, and American Smelting of Utah took over the mines. Total yields for 1929 were 3 million pounds of lead, 290,420 ounces of silver, 786 ounces of gold, and unknown amounts of zinc and tungsten. (Earlier miners apparently pocketed the gold, which didn't always make the official reports.[2]) World War II brought the U.S. Army to Cerro Gordo to mine for zinc, a strategic material.[2] The mines fell silent in 1959. In 1948, an RKO employee named Barbara left her assistant-director husband at Lone Pine and found herself on the Death Valley side of Cerro Gordo. In 1949, Barbara and a new boyfriend moved to Cerro Gordo as caretakers and were awarded ownership when the prior owner, W.C. Riggs, went bankrupt while owing them back wages. The boyfriend died and Barbara remarried (Jack Smith). In 1985 the couple transferred ownership to Smith's niece Jody Stewart, who with eventual husband Mike Patterson moved to the property and began restoring buildings for tourist and overnight use — including the American Hotel, the 1868 Belshaw House (now a bed-and-"make your own" breakfast), the general store (now a museum) and a 1904 bunkhouse (which accommodates 12 guests). Jody died in 2001, Mike in 2009. Today (2013) the property is owned by Mike's son Sean Patterson, a construction contractor in Bakersfield. A resident caretaker is on hand to help restore more buildings, give tours and prevent mischief. If you plan to visit, call 760-876-5030 before you go. Bring money for souvenirs and a donation. — Leon Worden 2013 Update 2018: The 300-plus acre Cerro Gordo property sold in June 2018 for an undisclosed sum above the $925,000 asking price. Major Sources Citation numbering in the text corresponds to the sources below. 1) "Cerro Gordo: A Ghost Town Caught Between Centuries" by Cecile Page Vargo, 2011. 2) Retired schoolteacher Robert Desmarais, the caretaker/historian at Cerro Gordo in April 2013. 3) Owner Sean Patterson's official Cerro Gordo website, CerroGordo.us. 4) "Desert Fever: An Overview of the Mining History in the California Desert Conservation Area," Bureau of Land Management report by Larry M. Vredenburgh, Gary L. Shumway and Russell D. Hartill, 1980.

LW2385a: 9600 dpi jpeg from digital image by Leon Worden. |

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.