|

|

Click image to enlarge

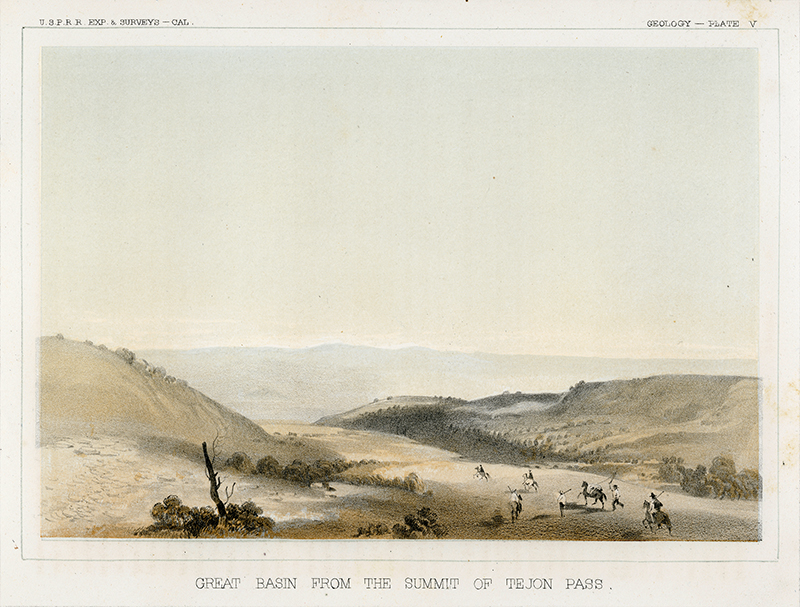

"Great Basin from the Summit of Tejon Pass." Original lithograph, 6x9 inches (full page 9x12 inches). From field sketch by Charles Koppel in 1853, lithograph by Thomas S. Sinclair of Philadelphia, printed by U.S. Government Printing Office, 1856. Plate V from Part 2 of Vol. 5 of "Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to ascertain the most practicable and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, made under the direction of the Secretary of War, in 1853-4, According to Acts of Congress of March 3, 1853, May 31, 1854, and August 5, 1854."

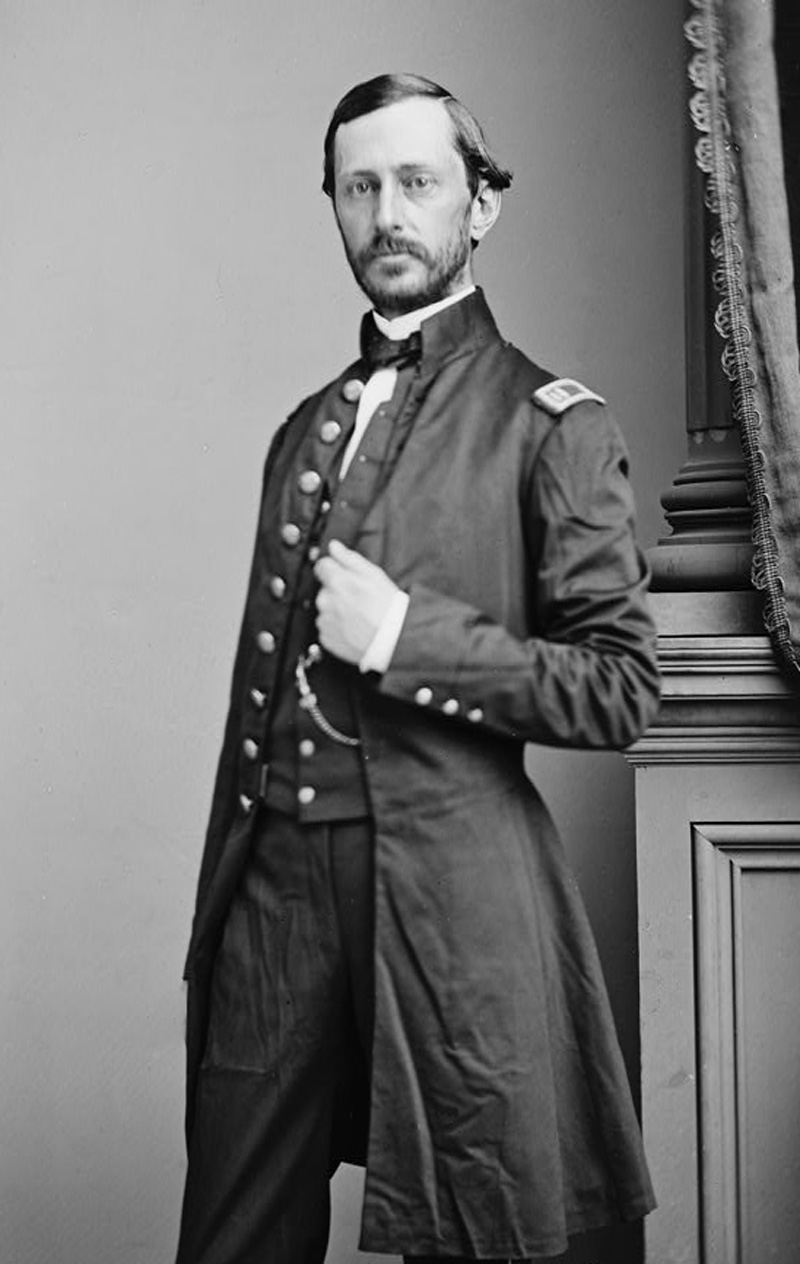

John C. Fremont in the mid-1840s and Edward F. Beale in the late 1850s weren't the only ones to search for a practical route west in the interest of America's "manifest destiny." In between came Robert Stockton Williamson (1825-1882), who, like Fremont, was an officer in the U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers (which later merged in to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers). In 1853, Williamson received orders from Secretary of War Jefferson Davis "to command an expedition and surveying party to ascertain the most practical and economical route from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean."

As one might expect, politicians and businessmen were fighting long and hard over the alignment of the future transcontinental railroad. Everybody wanted it, but not everybody could have it. Four potential routes were surveyed: a northern route over the northern Rocky Mountains to Puget Sound; a middle route through Salt Lake City (favored by Fremont's father-in-law, Sen. Thomas Hart Benton); a route through New Mexico and Arizona across the Mojave Desert; and a southern route from Texas to San Diego (favored by Secretary Davis). Ultimately, Benton won out, although the later Santa Fe Railroad followed a route that Davis would have appreciated. Additional explorations surveyed routes linking San Francisco to the Pacific Northwest, and San Francisco south to San Diego. It is this latter survey — the United States Pacific Railroad (U.S.P.R.R.) Expedition and Surveys-California — that interests us. Specifically, under his War Department orders dated May 6, 1853, Williamson was to set out from Benicia, which was the state capitol at the time, and "proceed to examine the passes of the Sierra Nevada leading from the San Joaquin and Tulare valleys, and subsequently explore the country to the southeast of the Tulare lakes, to ascertain the most direct practicable railroad route between Walker's Pass, or such other pass as may be found preferable, and the mouth of the Gila; from this point the survey will be continued to San Diego." Accompanying him, per the orders, were "Lieutenant J.G. Parke, topographical corps, and [] the following civil assistants, viz: one mineralogist and geologist; one physician and naturalist; two civil engineers; one draughtsman." Charles Koppel, a German artist, was the draughtsman; Koppel's sketches in the field were later transformed into lithographs that appear in sections of the official report to Congress on the various expeditions. The report spanned 12 volumes and took six years to compile and publish (1855-1861). The portions relevant to the Santa Clarita Valley (the trek south from Benicia) appear in Vol. 5, published in 1856. Traveling south, Williamson arrived in the Tejon area (Grapevine Canyon), where his geologist made note of the Peter Lebeck Oak with its curious inscription from 16 years prior. Then the party set up camp "near the east mouth of San Francisquito Canyon, close to the Road to the Mines," writes local historian A.B. Perkins. "San Francisquito Canyon is a writhing, narrow defile through granitic rocks with very steep gradients, definitely not adapted to any railroad project then or now. From the top of nearby Mt. Stoneman, Williamson first saw and realized the advantages of gradient and general accessibility of Soledad Canyon for railroad trackage. His reconnaissance, carried on during the next few days, bore out his theory." Williamson also left some other, more peculiar marks on the Santa Clarita Valley. Local historian Jerry Reynolds writes: "Most of Williamson's place names are still with us, such as Tick Canyon — he was attacked by the little insects there — Placerita, Lake Elizabeth and Hungry Valley. It was Lieutenant Williamson who misspelled Cañada del Buque [Ship Canyon], rendering it Bouquet Canyon. For the first time, also, Castac was shown as Castaic, while Islay [Tataviam for "berry"] became Hasley Canyon." While passing through Soledad Canyon, Williamson discovered a hitherto unknown variety of fish just east of today's junction of Soledad and Agua Dulce canyon roads. By custom, it was named for its discoverer — Gasterosteus aculeatus williamsoni. We know it better as the unarmored threespine stickleback. — Leon Worden 2017

LW2883: 9600 dpi jpeg from original lithograph purchased 2001 by Leon Worden.

|

SEE ALSO:

Williamson 1853: Report (1856)

Williamson 1853: Tejon Pass Entrance (1856)

Williamson 1853: Cañada de las Uvas (1856)

Williamson 1853: Great Basin View (1856)

Williamson 1853; SCV Geological Map (1856)

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.