Press Kit: Lang Station Golden Spike Centennial.

Chinese Historical Society of Southern California.

|

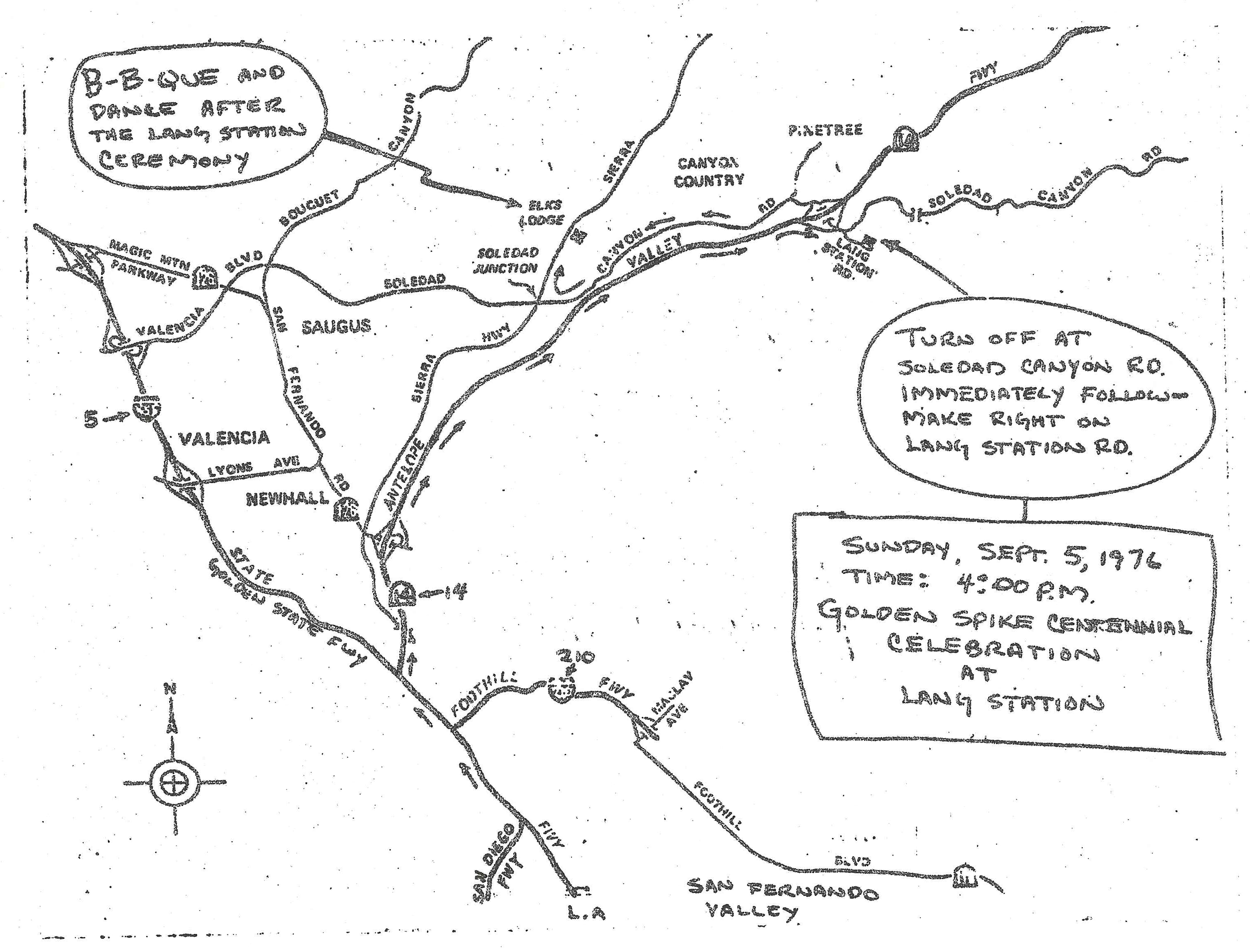

Cover Letter. Dear Editor: Enclosed are fact sheet, story, map and other data pertaining to the Centennial Golden Spike Ceremonies scheduled for September 5, 1976, at Lang Station, 15 miles northeast of Newhall, off the Antelope Valley Freeway. The Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society has invited the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California and other societies to participate in the ceremonies. The Chinese Society's President, Stan Lau, and Secretary of State March Fong Eu will present a bronze plaque to be installed as a commemoration to the 3,000-plus Chinese laborers. These laborers made possible the meeting of the South and North with the Southern Pacific Railroad 100 years ago. Firecrackers, lion dancers, and twin dragons will follow the presentation. A reenactment of the Driving of the Golden Spike is also scheduled.

Mockup of CHSSC Plaque See the installed plaque here.

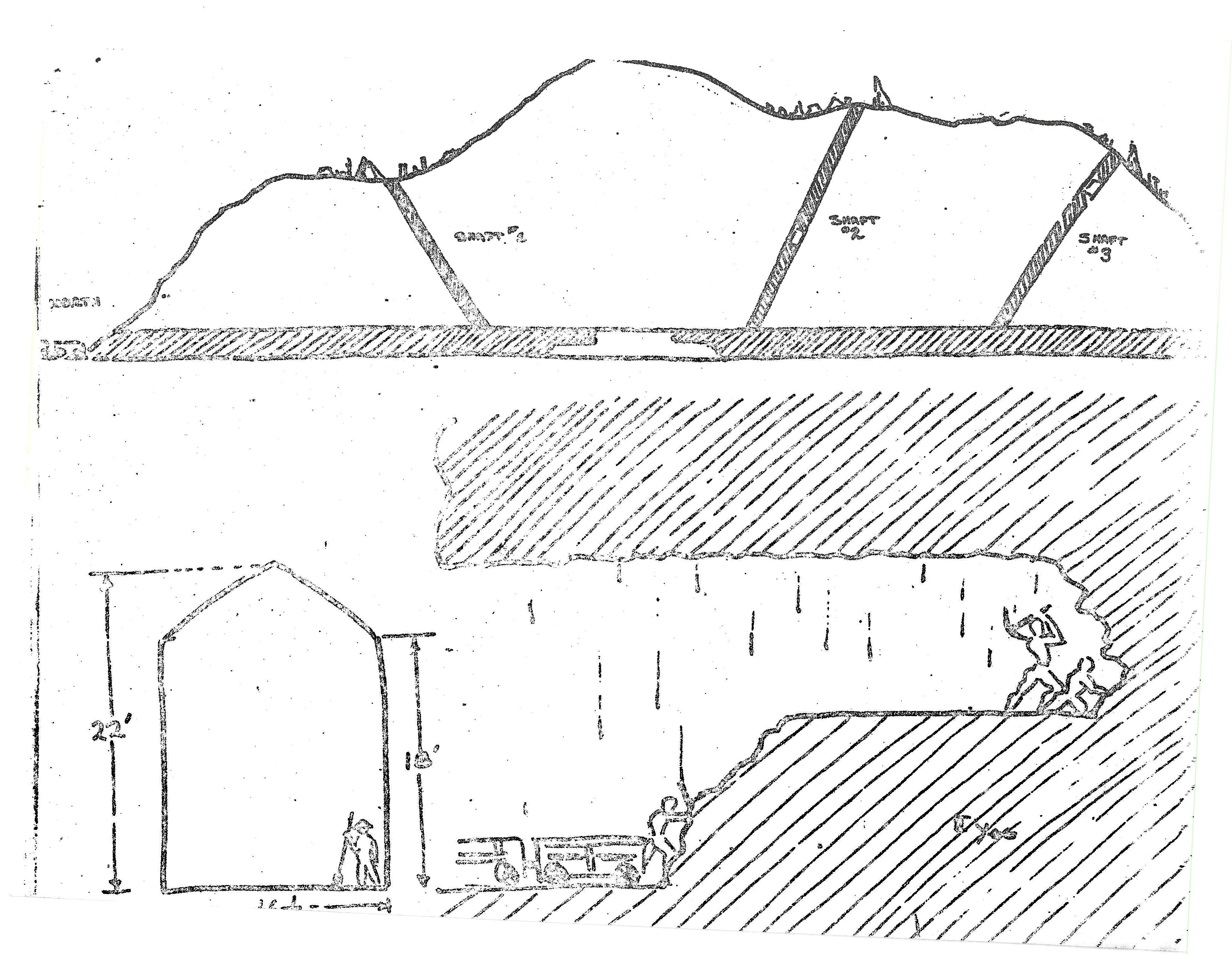

Abstract. Early in 1874, over 3,000 Chinese laborers were recruited to start a railroad from San Francisco southward, others to start from Los Angeles northward. Progress was made until the tunnel construction at San Fernando, a most formidable obstacle. Chinese laborers worked around the clock in three 8-hour shifts at a dollar a day. To hasten the task, the 7,000 feet, one and a third miles of solid rock, tunnel was to be dug from both ends simultaneously. On March 22, 1875, machinery, supplies and equipment arrived by ocean and land from San Francisco and Oregon. Tedious and crude methods of hammer and wedge chopped away the solid granite rock. Solid rock after being broken up soon became dirt, with oil and water seepage. Thin air necessitated shafts to be tunneled from mountain tops to the main tunnel areas, enabling air ventilation and also the lowering of men and equipment to inaccessible areas. Cave-ins, boiler explosions, cable breakages, loss of lives, oppressive heat and dampness slowed progress. In October 1875 there were thoughts of abandonment of the project due to the slow progress. Charles Crocker had great faith in the Chinese workers, so a target date of July 4, 1876, was set. Feverish excavation and digging activities hummed throughout the sections of tunnel. Finally on July 14, 1876, after one and a half years of continuous digging, success was close at hand; but would the two sections meet? As it turned out, they did, and there was great rejoicing from deep inside the tunnel. A miracle had joined the northern and southern sections of the San Fernando Tunnel. The ceremonies of this great event were held September 5, 1876, at Lang Station, some 15 miles from the San Fernando Tunnel. The mayors of San Francisco and Los Angeles were present to drive the Golden, last spike. Tracks for the entire railroad were laid by Chinese laborers, except for the last 1,000 feet. The remaining footage was to be laid by Caucasian workmen. Thousands of words were spoken — but not one word about the Chinese laborers who worked so diligently to meet the scheduled deadline. Instead, they were completely ignored and shunted aside by the insensitive citizens of California a hundred years ago. On September 5, 1976, Labor Day weekend, hundreds of Chinese from Northern and Southern California will gather at Lang Station to commemorate the ceremonies held 100 years ago. The Chinese Historical Society of Southern California will join the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society, California Historical Society, E Clampus Vitus, Historical Society of Southern California, Mint Canyon Lions Club, Newhall-Saugus Elks Lodge, Pacific Railway Historical Society, Santa Clarita Valley Bicentennial Committee and the Southern Pacific Company to conduct the ceremonies. (Activities include:) Presentation of a 12" x 18" bronze plaque by the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California with words in English reading:

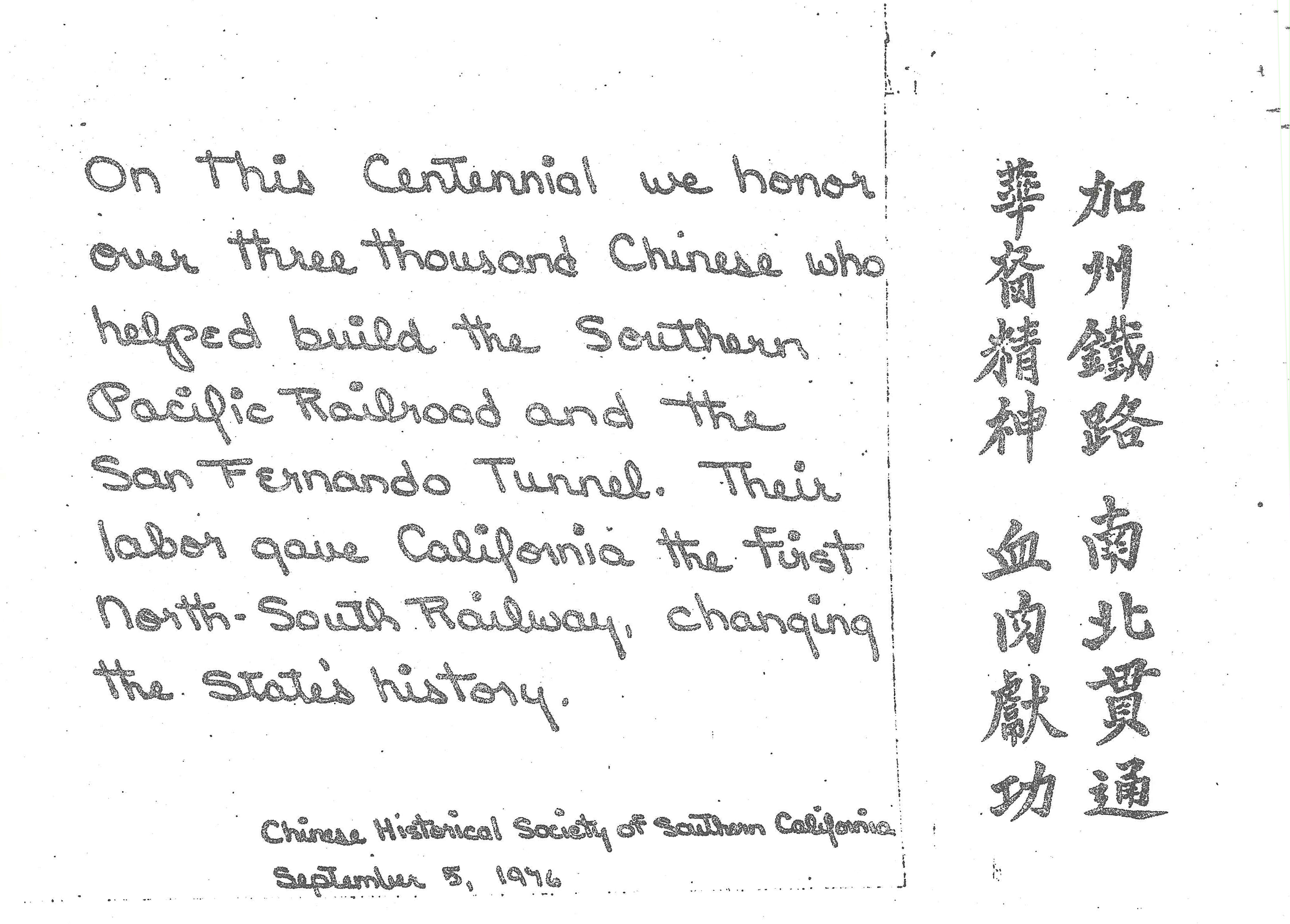

"On this Centennial we honor over three thousand Chinese who helped build the Southern Pacific Railroad and the San Fernando Tunnel. Their labor gave California the first North-South Railway, changing the State's history."

and in Chinese characters commemorating the event:

"California's railroad connecting the North and South, Accomplishments in sweat and blood from China's descendants."

Whistle-Stop Centennial. September 5, 1976 — a hundred years ago — a very significant event took place in Lang, California, in the Newhall area. On that day, and golden spike was driven in place to complete the Southern Pacific Railroad, linking California's two foremost cities, San Francisco and Los Angeles. The momentous event was destined to bring great economic prosperity to the state. The idea of such a tremendous undertaking had begin as a dream in the mind of Charles Crocker, president of the Southern Pacific, some time in the mid-1800s, a time when the country was beginning to recover from the wounds of war, a civil war in which brother fought against brother, father against son, friend against friend. What better way to bind the country together than with bands of steel and iron? Thus was born the idea of building railroads to link the East with the West, the North with the South, bringing the nation closer together. After years of planning, discussions and political wrangling, Crocker decided in October 1874 to meet with all interested parties to work out the details for completing the railroad. Final plans called for a railroad to be built from San Francisco going south to the Mojave desert and, at the same time, one to be started in Los Angeles going north to Lang. Then came the most difficult question — how to connect these two sections of railway. The only feasible solution was to build a tunnel north of San Fernando, going through the mountain range out to Soledad Canyon, and uphill to the Mojave desert. The tunnel would be 7,000 feet long, one and a third miles of solid rock, the greatest single engineering feat encountered so far by the Southern Pacific. At this point, there were many obstacles to be overcome before the project could get underway. Machinery and materials, cables and wagons had to be transported by oceanway from San Francisco; cedar lumber was to come from Oregon, also by ship. Huge engines were sent in sections and assembled on land, but one of the greatest problems was labor. Where and how could thousands of laborers be recruited to dig 7,000 feet of solid rock through a mountain? And if it were possible to obtain these workers, would they be able to withstand the rigors of such an arduous undertaking in addition to the unpredictable forces of Nature? Charles Crocker had the answer — Chinese laborers. With his past experience in hiring the Chinese to work on the Central Pacific Railroad, built by laying tracks across the mountainous Sierra Nevadas, Crocker knew that these workers were dependable, efficient, well qualified, and would cause little if any problems. And so, the Herculean project began. Early in 1874, thousands of Chinese laborers were recruited, some to start building the railroad from San Francisco southward, others to start from Los Angeles and heading north. In the meantime, the most formidable obstacle loomed ahead: The San Fernando Tunnel. A force of Chinese workers arrived in the first months of 1875 to an area that was hot, dry, desolate and mountainous. Their work was cut out for them. They were to work in three 8-hour shifts, day and night, at a dollar a day. To shorten the time required to complete the project, the tunnel would be dug from both ends simultaneously. On March 22, 1875, the excavation of the San Fernando Tunnel was officially begun with a huge explosion of Hercules blasting powder, rocking the mountain and surrounding area. From the very beginning, there seemed to be one obstacle after another. Since air jackhammers had not been invented in the 1870s, digging had to be done in a crude and laborious manner — a heavy wedge being held by one man while another struck it with a ponderous hammer. After a short period of digging and chopping, it was discovered that the mountain was saturated with oil and water. This, mixed with dirt and mucky clay, stuck to the shovels like putty. Deeper into the tunnel, the air became thinner, making it necessary to dig air shafts from the top of the mountain. Cave-ins, boiler explosions and the breaking of incline cables took a fearful toll of lives. Inside the tunnel, water dripped constantly from the roof and the sides, adding to the physical discomfort of the laborers. In the summer months, the oppressive heat and dampness made working conditions unbearable. Toward the end of October 1875, the difficulties of tunnel digging were becoming enormous. After eight months of slow, backbreaking labor, only 2,200 feet (less than 1/3 of the entire length) was completed. There were plans to abandon the tunnel, but rather than forfeit the bond designated by a contract with the federal government to build the railroad, the Southern Pacific decided to make a last great effort to complete the tunnel. Charles Crocker had an undaunted faith that his Chinese crew would stay with the job to the end — and his faith was not in vain. The target date was set for July 1, 1876. Inside the tunnel, work continued at a feverish pitch. Night and day, the chugging of steam engine pumps could be hear; echoes of underground explosions filled the air; a steady stream of wagons rolled into the tunnel with lumber and rolled out with rock and dirt; a heavy haze of dust hung constantly over both ends of the excavation. The digging continued. Inch by endless inch, the rock was chopped form the bowels of the mountain. Foot by endless foot, the tunnel was coming closer to reality. The weary days turned into weeks, and progress seemed agonizingly slow, but the long-suffering Chinese laborers plodded on — and on. During the long, dreary days and nights, many thoughts must have passed through the minds of these lonely men, so far from home. Time and again, they must have returned in poignant memory to their village homes thousands of miles away, where warmth and love had been shared by family and friends; their hearts must have aced longingly for some wifely comfort at the end of each wearisome day; those who were fathers must have wished desperately to be able to watch a stalwart son grow to manhood, or to see a dainty little girl-child take her first faltering steps. Yet all these normal human pleasures were denied to these Chinese laborers, due to a number of cruel and unjust immigration laws passed by the U.S. government, and aimed directly at them. In spite of the harassment and hardship, the grueling work and the drudgery, the Chinese kept digging and chopping into the tunnel. Finally, on July 14, after a year and a half of continuous excavating, success seemed close at hand. The question uppermost in everyone's mind was: Would the two sections meet? Or would one overshoot the other? As it happened, both sections met on target, and there was great rejoicing deep inside the tunnel. A miracle had indeed joined the northern and southern portions of the Southern Pacific Railroad. The ceremonies to celebrate this great event were held on September 5, 1876, at Lang Station, 15 miles from the San Fernando Tunnel. Tracks for the entire railroad had already been laid by Chinese laborers, except for the last 1,000 feet, which had been set aside for this occasion to be laid in place by Caucasian workmen. Thousands of words were spoken at the ceremony, but not one word of mention about the Chinese laborers who had worked so diligently to complete the tunnel on schedule. Instead, they were completely ignored and shunted aside by the insensitive and indifferent citizens of California. And that's the way it was, a hundred years ago. However, on this September 5, 1976, these courageous men will not be forgotten. They will be honored in memory with gratitude and respect by members and friends of the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California. They Society will be dedicating a plaque at Lang Station to commemorate the contributions made by these thousands of Chinese laborers who, though considered slight of build and small in stature, proved that they were actually "ten feet tall" by virtue of their endurance, patience, courage, and indomitable spirit. And it was this same spirit and perseverance that contributed so greatly to the fulfillment of an "impossible dream."

Download original pdf here. Courtesy of Cynthia Neal-Harris. Document file.

|