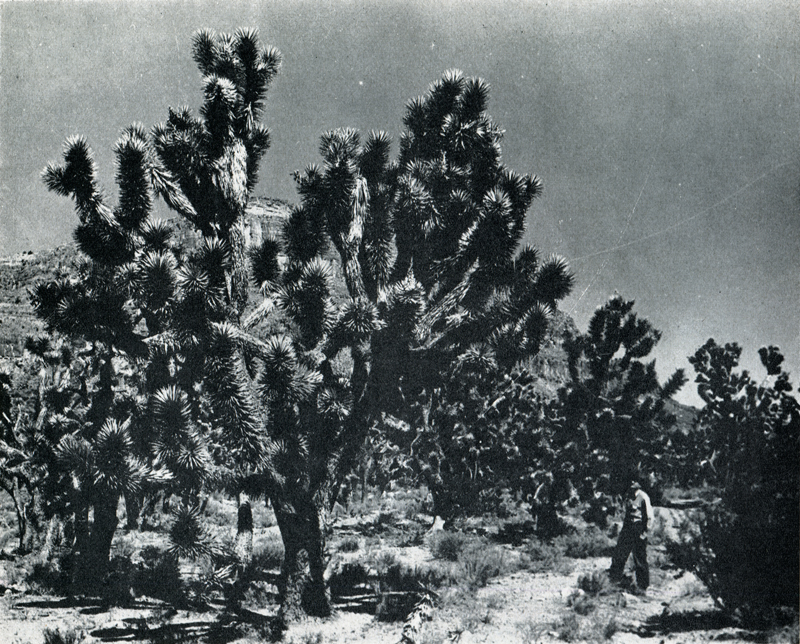

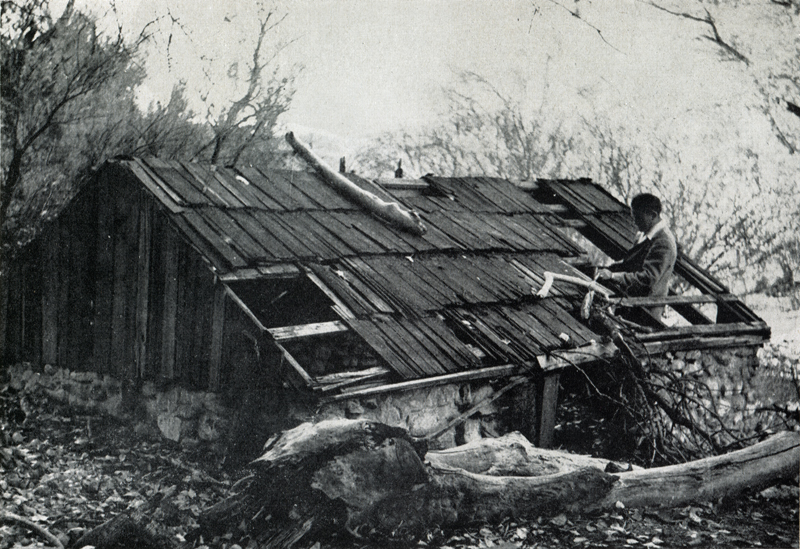

More than once in the last century, industrialists have cast covetous eyes toward the great Joshua forest which extends over much of California's Mojave desert.

Experiments have been conducted in many laboratories in an effort to find a commercial use for the wood. Here is the story of one experiment

which failed, and there are many who will share the author's feeling that failure in this instance was a fortunate circumstance. — Desert editor Randall Henderson

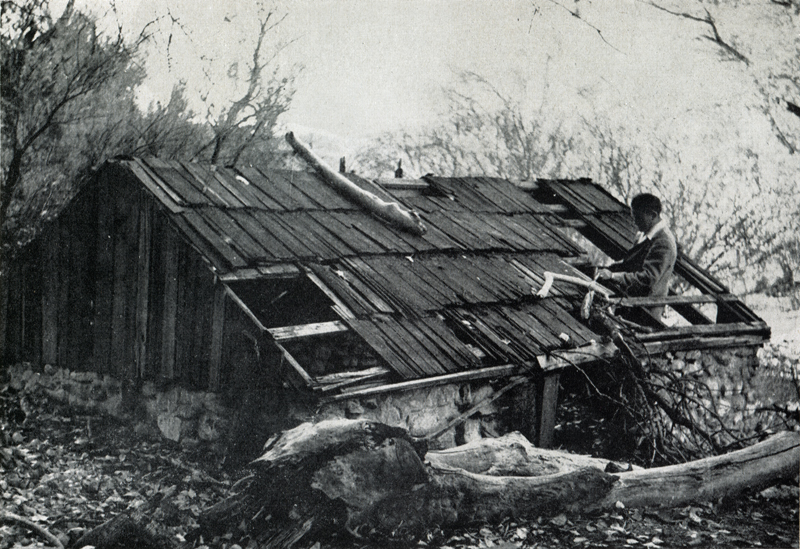

Original caption: "This is believed to be the ruins of one of the old mill buildings, designed to make

paper pulp from the Joshua trees." Click image to enlarge.

|

A single paragraph in an old botany book gave me the first clue to a scheme which many years ago threatened to rob the western desert of its Joshua trees. In "Wildflowers of California" by Mary Elizabeth Parsons, published in 1913, I read:

"Joshua wood furnishes excellent material for paper pulp and some years ago an English company established a mill near Ravenna in Soledad Canyon Pass, for its manufacture. It is said several editions of the London Journal were printed upon it but owing to cost of manufacture the enterprise was abandoned."

That was all I had to go on.

To one who has watched and loved the desert for over 30 years, the suggestion of denuding the desert of its Joshua trees to make paper was a sacrilege. I wanted to know more.

A search of the old history books in the libraries of Los Angeles and Sacramento brought to light some rather vague information.

Persistent inquiries unearthed other facts. A letter to Lord Camrose and Arthur E. Watson, proprietor and editor of the London Daily Telegram, turned up nothing of importance since their records had been destroyed. Another to the Congressional Library in Washington, D.C., was slightly more successful. An inquiry to the Agricultural College in Corvallis, Oregon, brought me a copy of an article published in 1891, containing a brief reference to the Joshua tree in relation to paper.

Piecing together the information from these and other sources I was able to reconstruct the story as follows:

About 1870, experiments led a few optimistic people in California to put value on the Joshua trees, not for their strange appearance and wax-like blossoms, but as a possible source of paper.

Original caption: "Joshua forest on California's Mojave desert." Click image to enlarge.

|

Finally the Atlantic and Pacific Fiber Company of London, England, established in 1884, with Colonel Gay and a Mr. Payne as managers and J.A. Graves of Los Angeles as attorney, came into the picture. They acquired 5,200 acres of Joshua covered land in the Antelope Valley of California for the purpose of converting the trees into paper. They also contracted to furnish the London Daily Telegraph with Joshua tree paper.

Just why a London firm should cast covetous eyes on the California Joshua tree is anyone's guess.

The land was located between Alpine and Ravenna in Soledad Canyon Pass[1] northeast of Los Angeles, California. The London company employed a crew of Chinese to cut the Joshuas into two foot lengths and haul them to Ravenna where they had converted an old stamp mill into a plant for the reduction of the wood to pulp. Great quantities were shredded, compressed and baled for shipment to London where the pulp was to be turned into paper.

At the District Agricultural Fair which took place in Southern California the latter part of October a year later, there was an exhibit of shredded Joshua wood and several good sized logs, brought in from the Mojave desert. Manufacture of products from Joshua trees was heralded as a "new industry."

It was stated that the manufacture of excellent quality paper from Joshua trees growing on the Mojave desert was being tested at the Lick Paper Mill at San Jose, by parties who planned to obtain control of all the paper mills on the coast and set them to manufacturing Joshua paper exclusively. This article went on to say the "cactus" paper was very strong and the supply of material unlimited.

In 1891, an article mentioned a mill on the Colorado River, built about 1871, which worked up Yucca stems and leaves into paper pulp. After shipping large quantities of both brown and white paper, the mill closed and reopened a couple of times before the venture finally was abandoned.

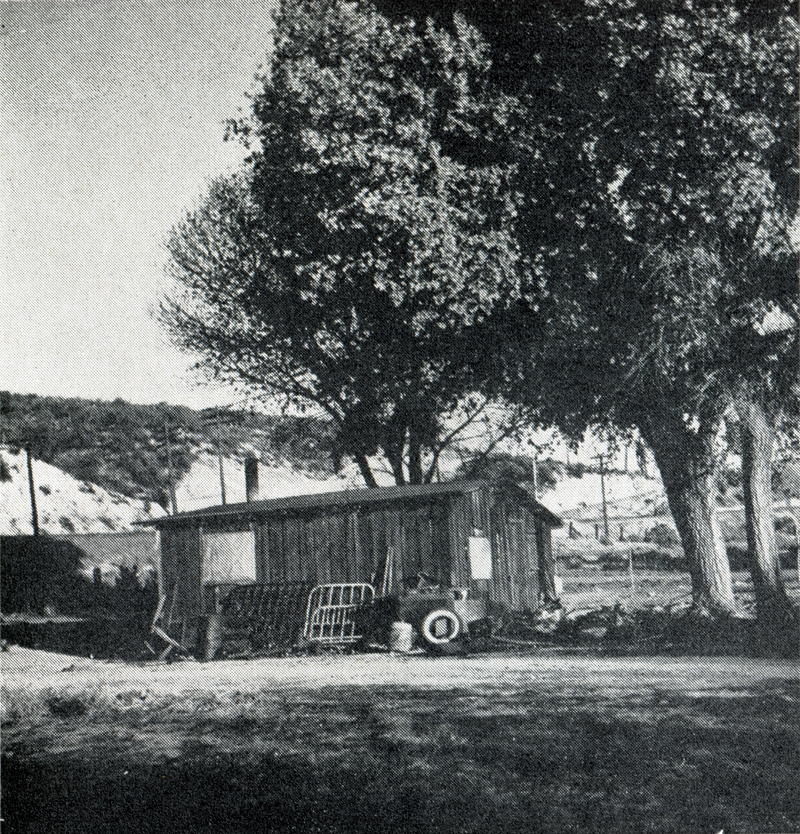

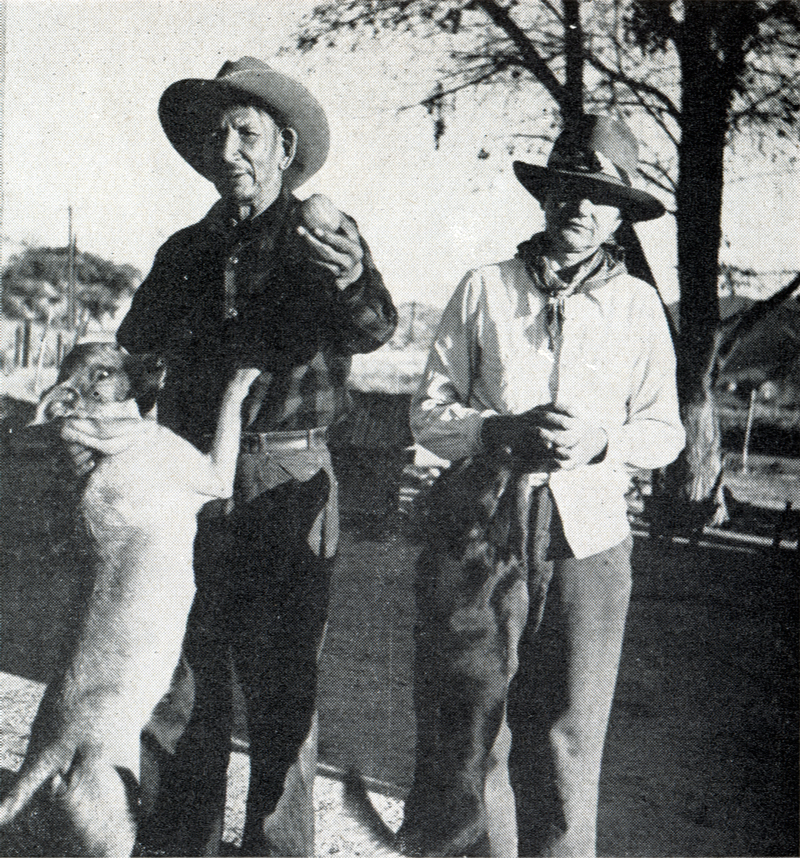

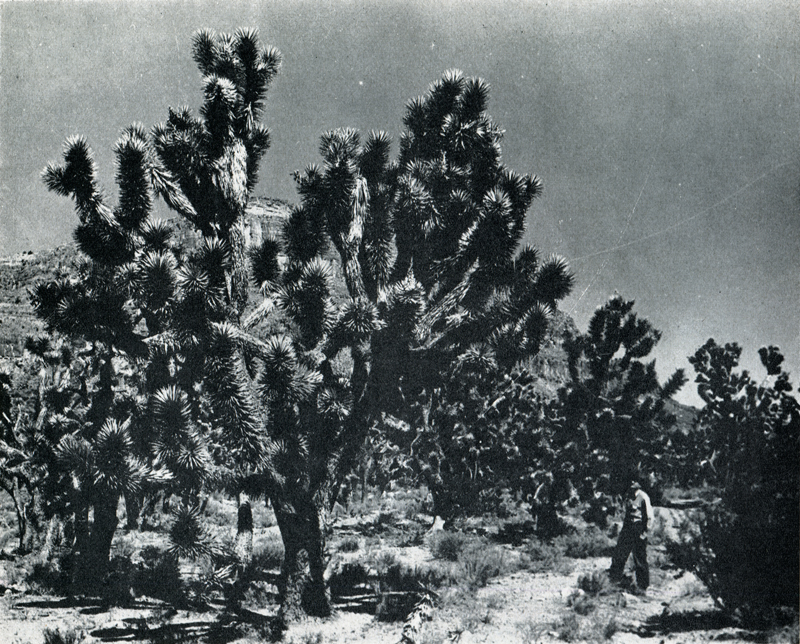

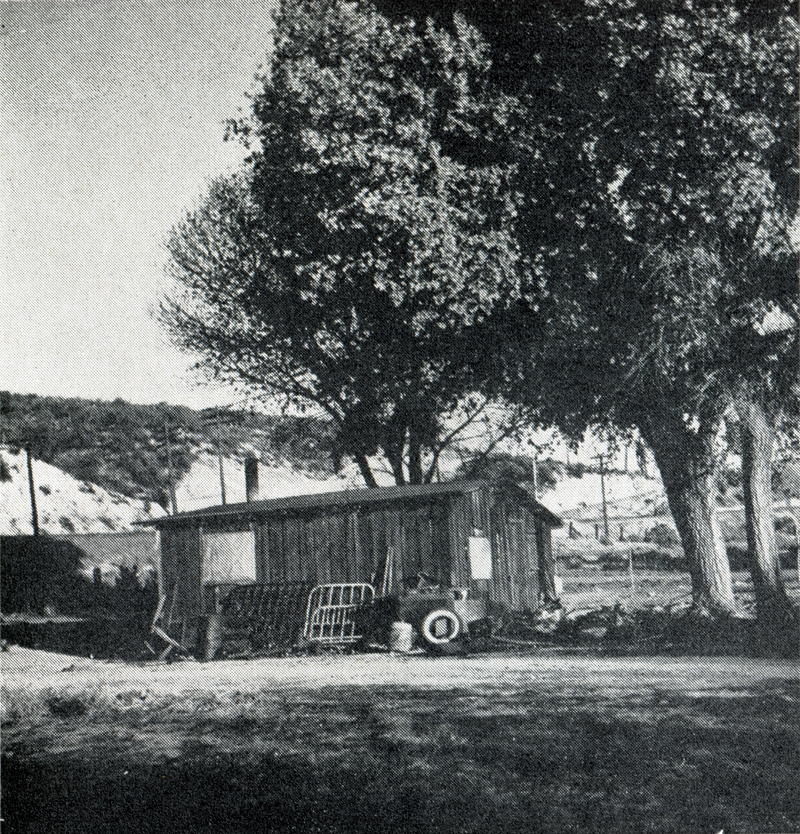

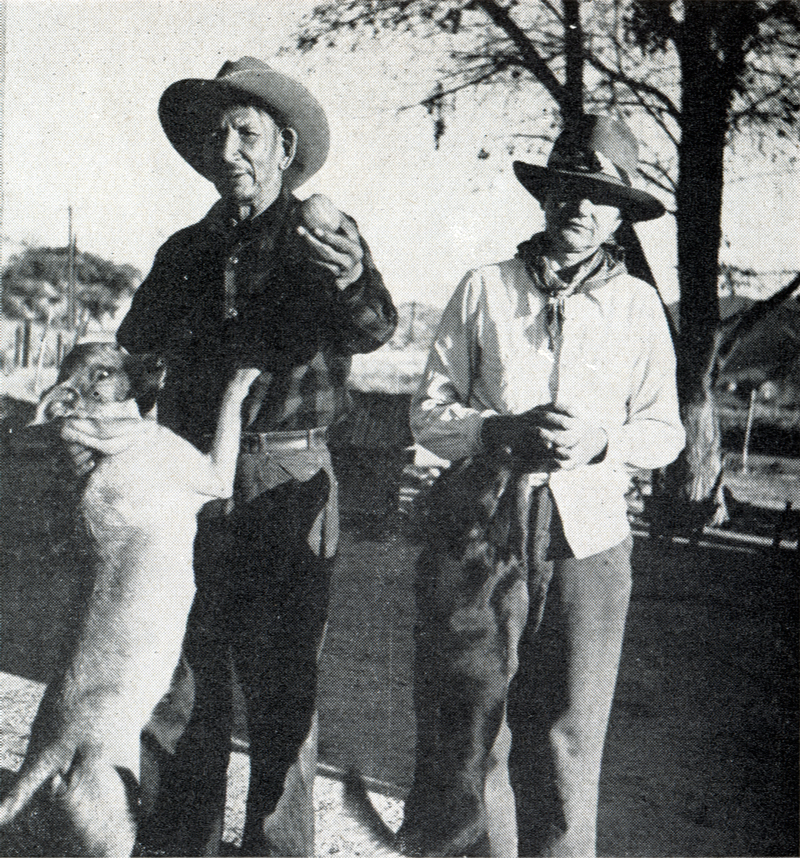

Original caption to this and the next photograph: "The cabin in which Indian John Peake and his wife live with their big family

and [sic] dogs and cats, near the mouth of Soledad Canyon." Click images to enlarge.

|

Another publication, in November 1894, gave three more uses of the Joshua tree, facetiously referring to them as "monkey-puzzle trees" since it would puzzle a monkey to climb one. It mentioned a factory making tree protectors and told of a Los Angeles concern manufacturing Joshua tree surgeon splints. It went on to describe how a factory peeled the trunks, much as one does a potato, to make a sort of veneer which was stained the color of various woods. The publication ended by saying the Joshua veneer proved to be entirely too porous, absorbing great quantities of color so the project was abandoned.

Another version of the paper scheme revealed that the first shipment of the pulp to England spoiled on the way and that paper made of a subsequent shipment proved to be of inferior quality.

As late as 1933, information on Joshua tree paper was being printed. Charles Francis Saunders in "Western Wildflowers" wrote: "... the trees seemed to be of no value until someone thought of them as possible paper stock. At one time, now some 50 years ago, a small pulp mill was built at Ravenna in Soledad Canyon Pass about 60 miles north of Los Angeles. Paper was manufactured and shipped to various parts of this country as well as to England where a few editions of the London Daily Telegraph are said to have been printed upon it."

It is quite possible the Atlantic and Pacific Fiber Company was heartily sick of its project when a cloudburst solved the dilemma in February 1886, by destroying the mill in Soledad Canyon Pass and routing the Chinese workmen.

Today, if you want to visit the site you ask permission of John Peake, an Indian, who with his wife and several cats and dogs, occupies a little cabin at the gate leading into the canyon.

Peake told us he had heard of the mill. He pointed in the general direction of the site—but assured us there wasn't a thing to see.

We parked the car under a group of cottonwoods a quarter of a mile beyond the gate and started along the boulder-strewn bed of a dry arroyo, my husband leading.

We parked the car under a group of cottonwoods a quarter of a mile beyond the gate and started along the boulder-strewn bed of a dry arroyo, my husband leading.

For two hours we searched both sides of the riverbed and were about ready to agree with Peake that there wasn't anything to see when one of our party let out a whoop.

"Forward and right," he shouted. "You'll have to crawl under this fence and climb the bank." Hot and tired we finally arrived at the edge of Mill Creek, a tiny crystal stream. And there were the timbers and remnants of a building put together with square nails. Not far from this venerable relic was a circular stone tower-like structure, fast falling into decay. What part it played in the Joshua paper project, I do not know. Scattered beneath dense brush were all sorts of broken timbers and quantities of rusty iron.

After photographing the ruins and attempting to visualize the old Chinese camp, we headed for the car. It was nearly sundown when we closed the gate and waved to John Peake and his wife with their big family of pets surging about their feet. Looking back, the mill site was lost in wooded shadows.

Far down the canyon we edged into the long line of cars creeping toward Los Angeles. I was glad the Joshua paper project had failed. It was unthinkable to imagine the western desert bereft of their most picturesque botanical denizens.

Webmaster's Note.

1. Ravenna and Alpine were Southern Pacific rail stops at the time. The Ravenna depot was located southwest of Acton (between Lang and Acton);

Alpine was located northeast of Acton (between the Acton and Lancaster depots). Thus the area that was stripped of Joshua trees seems to be Acton.