|

|

The Russian-Alaksan Bell from Mission San Fernando at Rancho Camulos.

News reports, 1923.

|

Webmaster's note.

This story was absurdly told in the 1920s to the extent that it makes it sound like the bell was traded for food in California to save starving Russians in Alaska. In fact, Spain, coming up from the south, and Russia, coming down from the north, were in a race to colonize the West Coast of North America, and Count Rezanov, the mastermind behind the Russian American Company — think Hudson's Bay Company or the Dutch East India Company — brought the bell and several other bells and furs with him to Yerba Buena (San Francisco) in 1806 as bribes in hopes of persuading California government officials to allow his company to establish colonies in California. Spain, smartly, didn't allow its California colonists to enter into treaties, but that didn't necesarily stop them; Spain was far away. Rezanov, who had won over the California officials and fell in love with the San Francisco (later Santa Barbara) commandant's 15-year-old daughter, persisted. (The girl's father is the person who placed our subject bell at San Fernando.) Awaiting papal dispensation to marry her — Rezanov's first wife had died in childbirth — Rezanov was carrying a proposed treaty to the tsar in 1807 when he contracted fever in Siberia and died. Rezanov's death delayed but did not halt the tsar's plans. In 1815, Spanish California soldiers would execute a group of Russian American Company traders who sought to control the Channel Islands. The one place in Alta California where the Russians succeeded was in Solano County (Bay Area), where they established and maintained Fort Ross from 1812-1842. Spanish/Mexican Cailfornia's response was to establish Mission San Rafael Arcángel in 1817 and Mission San Francisco Solano in 1824 to bolster the the Californio foothold in the region. The Solano Mission — the northernmost — was the only one established after Mexico declared independence from Spain in 1821.

San Fernando Bell. An Inscription in a Language Now Almost Extinct, the Key to Which Was Supplied by a Professor at Berkeley, Gives Aid in Tracing History of the Relic.

By Otis M. Wiles | (Syndicate Unidentified)

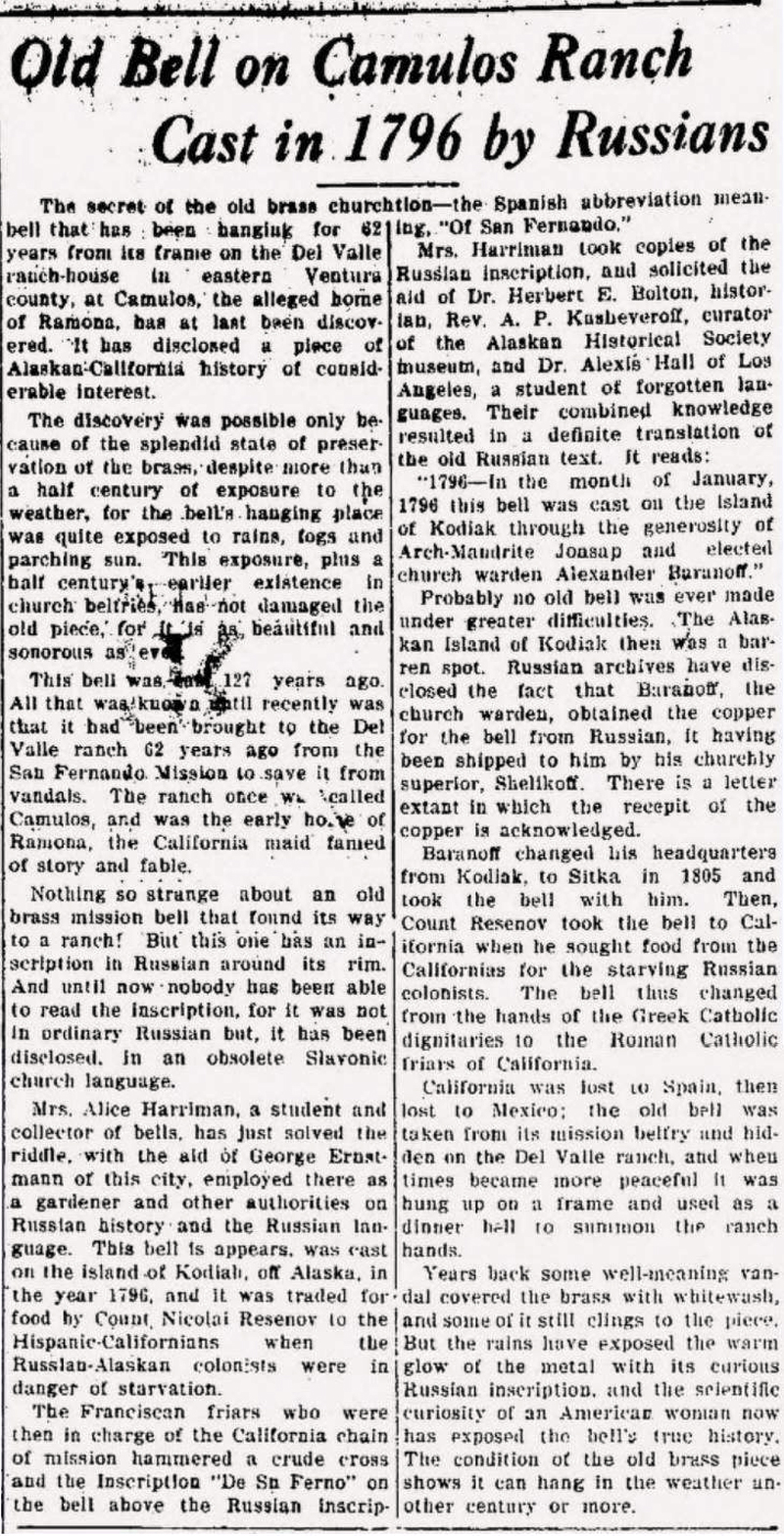

An old and battered bell, hanging in an orange grove where Ramona played in the days of her childhood[1], has rung a new note in the song of California's mission history. After a silence of one hundred and twenty-seven years the ancient bell has spoken, and the tale it has told is destined to alter certain chapters of the story of El Camino Real. It may prove facts of California's history which have existed only as theory. Further, it may refute one or two other phases of the King's Highway chronicles which have always been accepted as historical fact. And it has been proclaimed by several historians as one of the most important historical discoveries of a human interest nature ever made on the Pacific Coast. Alice Harriman, of Los Angeles, noted campanologist[2] and author, is accredited with uncovering the veiled past of the aged bell. Three years ago Mrs. Harriman first saw the bell as it swung in an orange grove at "Camulos," where Ramona spent her girlhood days, and now at the Del Valle ranch. Since then, she has devoted her time to tracing back the almost obliterated story of the bell. She announced yesterday the completion of her research work, in which she has been assisted by noted American and Russian authorities. The bell is not of Spanish origin. Nor did it come to California from Mexico, Peru, Chill [Chile?], Massachusetts or Russia — where practically all the famous bells of the world were cast. The Camulos bell was made on the island of Kodiak, Alaska, and presents the first glimpse into a phase of the earliest settlement of Russian America, now known as Alaska, which hitherto has been unknown to modern historians. The inscription on the Camulos bell, written in a forgotten language, betrays the secret. It reveals that it was cast at Kodiak in 1796, that it was traded for food by Count Nicolai Resenov [Rezanov], and that until sixty years ago it was hung in the famed San Fernando Mission. "I have found bells from Mexico, Spain, Peru, Chill, Belgium, Massachusetts, Sitka and Russia," said Mrs. Harriman yesterday. "But not until three years ago did I realize that I was to discover one of the most historical bells ever found." She told of a visit to Camulos when she first saw the bell in the orange grove. But the inscription was in Russian script. The Del Valle family knew little concerning the bell, other than it had been removed from the old San Fernando Mission to save it from vandals sixty-two years ago, and that ever since then it had been exposed to the ravages of the weather on the Del Valle ranch. A crude cross and a stenciled inscription "De Sn FERNo," hammered on the bronze surface by the Franciscan fathers, showed it had once hung in San Fernando Mission. Russian authorities could not translate the inscription around the lower rim. With the assistance of Dr. Herbert E. Bolton of the University of California, noted historian[3], Mrs. Harriman learned that it was in the old Slavonic church language, now practically extinct. She appealed to Rev. A.P. Kashereroff, curator of the Alaskan Historical society, and she learned portions of the inscription: "Island of Kodiak — Alexander Baranoff — Month of January." Two big gaps in the inscription could not be read from the photographs by Dr. Kashereroff. She then sought the aid of Dr. Alexis Kall of this city, a student of the forgotten language[4]. The complete inscription read: "1796 — In the month of January, this bell was cast through the generosity of Arch-Mandrite Joasaph and elected church warden Alexander Baranoff." "Now how did it get down into California, into an orange grove," Mrs. Harriman asked, "cast on a barely settled island with the wild, wide waters of the North Pacific pounding on the shores of the bay near where it was cast by a Greek Orthodox arch-abbot for a sponsor — how does it come that it was for years the bell for the Roman Catholic Franciscan Mission of San Fernando, in the lovely valley of the same name?" "The answer, practically certain, and endorsed by historians and campanologists in California, Washington and Alaska, is that when Baranoff changed his headquarters from Kodiak to Sitka in 1805 he brought the bell with him." "When Count Resenov visited Sitka and found the little settlement in such sore straights [sic] for food, he took the Juno [a vessel] and came to California for food for starving Sitka. Knowing as the Russians did, that the Spanish settlements of California had missions and that wherever there are missions, bells are needed, Resenov brought this bell with other things that he thought he could exchange [in] the southern land for grain and meat. When it was traded, the San Fernando inscription was stenciled upon it. "It may have been that the bell was brought by the Russians who hunted for otter on the Channel Islands; but the bells are ungainly things to handle and it is doubted if there is any explanation to be found than the one endorsed by these highest in authority on Pacific Coast History. "The material in the bell also has an interesting history as research in Russian archive show [sic]. Baranoff wrote to Shelikoff[5], his superior in Russia and at whose insistence the bell was first cast, that the copper he sent — meaning Shelikoff — had been received and that "that Englishman, Vancouver," had sent him some tin. "Baranov, most fortunately, even wrote to Shelikoff revealing the name of the founder of this wonderful bell. It was Sapoknikoff." Mrs. Harriman stated that most of her positive information concerning the bell was found in Tekmanieff's history. 1. Ramona was a fictional character in Helen Hunt Jackson's 1884 novel of the same name. The characters and setting for the novel are loosely based in part on Rancho Camulos and some of its residents. 2. One who studies bells. 3. Herbert Eugene Bolton (1870-1953) chaired the history department at the University of California, Berkeley, for 22 years and was an authority on the Spanish-American Borderlands (the territories that became California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas). 4. A pianist, linguist and close friend of composer Igor Stravinsky, Alexis Kall (1878-1940?) taught the history of music at the Imperial University in St. Petersburg, Russia, until he was driven out by the 1917 revolution. In 1919 he ended up in Los Angeles where he started the Institute of Musical Art and got Stravinsky into the movies. 5. Grigory Ivanovich Shelekhov (1747-1795) was a Russian fur trader who arrived in Alaska in 1784 and founded a predecessor of the Russian American Company. In 1890 he hired Alexandr Baranov to run it. News story courtesy of Jason Brice and Tricia Lemon Putnam.

Old Bell on Camulos Ranch Cast in 1796 by Russians. Oxnard Daily Courier | October 31, 1923.

The secret of the old brass church bell that has been hanging for 62 years from its frame on the Del Valle ranch-house in eastern Ventura county, at Camulos, the alleged home of Ramona, has at last been discovered. It has disclosed a piece of Alaskan-California history of considerable interest. The discovery was possible only because of the splendid state of preservation of the brass, despite more than a half century of exposure to the weather, for the bell's hanging place was quite exposed to rains, fogs and parching sun. This exposure, plus a half century's early existence in church belfries, has not damaged the old piece, for it is as beautiful and sonorous as ever. This bell was cast 127 years ago. All that was known until recently was that it had been brought to the Del Valle ranch 62 years ago from the San Fernando mission to save it from vandals. [That's one possible motivation — Ed.] The ranch once was called Camulos, and was the early home of Ramona, the California maid famed of story and fable [Ramona was a purely fictional character — Ed.]. Nothing so strange about an old brass mission bell that found its way to a ranch! But this one has an inscription in Russian around its rim. And until now nobody has been able to read the inscription, for it was not in ordinary Russian but, it has been disclosed, in an obsolete Slavonic church language. Mrs. Alice Harriman, a student and collector of bells, has just solved the riddle, with the aid of George Ernstmann of this city, employed there as a gardener and other authorities on Russian history and the Russian language. This bell, [it] appears, was cast on the island of Kodiak, off Alaska, in the year 1796, and it was traded for food by Count Nicolai Resenov [aka Rezanov] to the Hispanic-Californians when the Russian-Alaskan colonists were in danger of starvation. The Franciscan friars who were then in charge of the California chain of mission[s] hammered a crude cross and the inscription "De Sn Ferno" on the bell above the Russian inscription — the Spanish abbreviation meaning "Of San Fernando." Mrs. Harriman took copies of the Russian inscription, and solicited the aid of Dr. Herbert E. Bolton, historian, Rev. A.P. Kasheveroff [sic], curator of the Alaskan Historical Society museum, and Dr. Alexis Hall of Los Angeles, a student of forgotten languages. [He was much more than that — Ed.] Their combined knowledge resulted in a definite translation of the old Russian text. It reads: "1796 — in the monthof January, 1796 this bell was cast on the Island of Kodiak through the generosity of Arch-Mandrite Joasap [sic] and elected church warden Alexander Baranoff." Probably no old bell was ever made under greater difficulties. The Alaskan Island of Kodiak then was a barren spot. Russian archives have disclosed the fact that Baranoff, the church warden, obtained the copper for the bell from Russia, it having been shipped to him by his churchly superior, Shelikoff. There is a letter extant in which the receipt of the copper is acknowledged. Baranoff changed his headquarters from Kodiak to Sitka in 1805 and took the bell with him. Then, Count Resenov took the bell to California when he sought food from the Californians for the starving Russian colonists. The bell thus changed from the hands of the Greek Catholic dignitaries to the Roman Catholic friars of California. [Editor's note: Shelikov founded a predecessor of the Russian American Company and hired Baranov to run it in 1890. Rezanov was the mastermind behind the eventual Russian American Company, which purpose was to establish colonies on the West Coast of North America. The churchly references are nice, but Russian and Spain were in competition for control of Western land and trade. Rezanov hoped to gain California officials' acquiescence for Russia to establish colonies in areas under Spanish rule. He was unsuccessful; he died in 1807.] California was lost to Spain, then lost to Mexico; the old bell was taken from its mission belfry and hidden on the Del Valle ranch, and when times became more peaceful it was hung up on a frame and used as a dinner bell to summon the ranch hands. Years back some well-meaning vandal covered the brass with whitewash, and some of it still clings to the piece. But the rains have exposed the warm glow of the metal with its curious Russian inscription, and the scientific curiosity of an American woman now has exposed the bell's true history. The condition of the old brass piece shows it can hang in the weather another century or more. News story courtesy of Jason Brice. Discovery of Old Brass Mission Bell Uncovers a Romance of Five Nations.

Feature as published in Shamokin (Penn.) Dispatch | Saturday, November 24, 1923.

Mrs. Alice Harriman, student and collector of bells, has just solved, with the help of several authorities on Russian history and language, the riddle of the old brass church bell that has been hanging for 62 years in the Del Valle ranch house in Southern California. This ranch was the early home of Ramona, the Californian maid, famed in story. [Ramona was a fictional character — Ed.] This bell, it appears, was cast on the island of Kodiak, off the coast of Alaska in 1796, and was later traded for food by Count Nicolai Resenov [aka Rezanov] to the Hispanic Californians, when the Russo-Alaskan colonists were in danger of starvation. The Franciscan friars then in charge of the chain of Californian missions hammered a rude cross and the inscription "De Sn Ferno" (of San Fernando) on the bell just above the Russian legend, which was almost obliterated. Mrs. Harriman sought the aid of Dr. Herbert E. Boulton, historian [sic; s/b Bolton]; Rev. A.P. Kasheveroff [sic], curator of the Alaskan Historical Society Museum; and Dr. Alexis Kall, of Los Angeles, a student of ancient languages, and they puzzled out the old inscription as follows: "1796 — in the month of January, 1796, this bell was cast on the Island of Kodiak through the generosity of Arch-Mandrite Joasaph and elected church warden Alexander Baranoff." The old bell was cast under many difficulties. Baranoff, the church warden, obtained the copper for the bell metal from Russia, and there is a letter extant bearing his thanks to his church superior, Shelikoff, for the trouble he took. Baranoff went to Sitka in 1805 and took the bell with him. Then came lean days and hungry ones; so Count Resenov carried the bell to California to trade it for food. Much has happened in Alaska and in California during the 127 years that this old brass bell has been hanging out in the rains, the fog and the sun. Alaska, bought by the U.S., has proved a treasure house of natural resources. California, lost by Spain, was later lost also by Mexico, the old bell being taken from its mission house belfry and hidden on the Del Valle ranch and, when times grew more propitious, taken from hiding and used as a dinner bell to summon the ranch hands. Its voyages and vicissitudes have done little harm to the old brass. Some well meaning vandal put a coat of whitewash on it some years ago, but that has washed off in the rain and the warm glow of the old metal, untarnished by age, still remains. It looks as though it could well withstand several centuries more of use. News story courtesy of Jason Brice.

|

Secularization & Sale, 1830s-40s (Engelhardt 1927)

Vischer 1865

Dedication 1925 x4

Bell at Camulos: Alaska Report 1923

Bell at Camulos (News reports 1923)

Bell at Camulos (Engelhardt 1927)

Pre-Restoration

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.