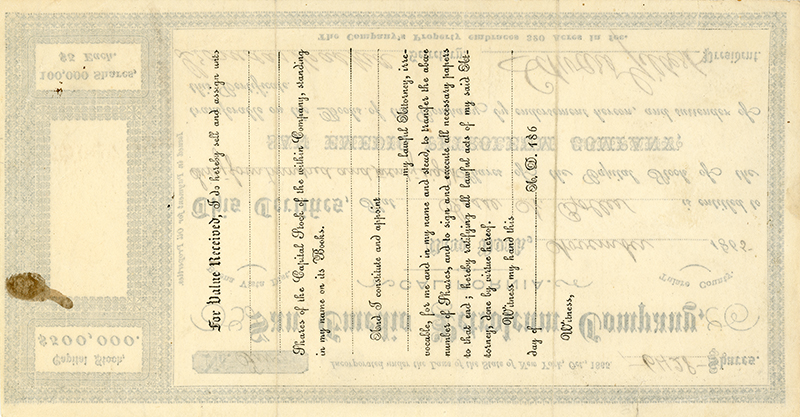

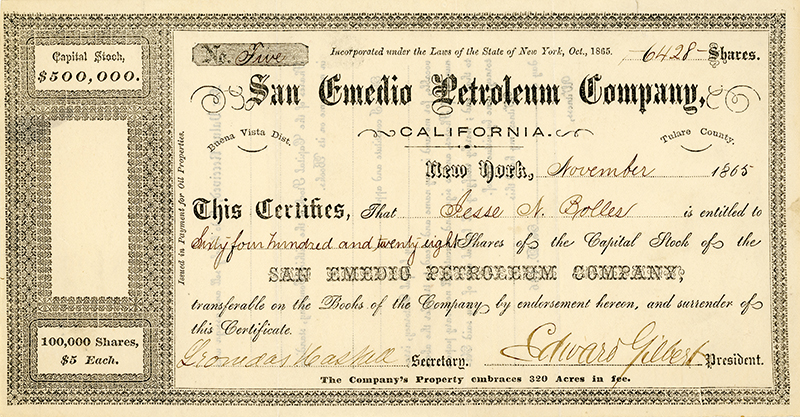

San Emedio Petroleum Company Stock Certificate

San Emigdio Region

Click image to enlarge

| Download archival scan

San Emedio Petroleum Company stock certificate for 6,428 shares, issued at New York in November 1865 to Jesse N. Bolles. Buena Vista District, Tulare County (at the time). Incorporated in New York, October 1865, by Edward Gilbert, president, and Leonidas Haskell, secretary. 8¾x4½ inches, uncanceled. Probably unique for this company. This one is a mystery. We find no record of this company. The certificate states that the company holds (petroleum) mining claims on 320 acres of government land.

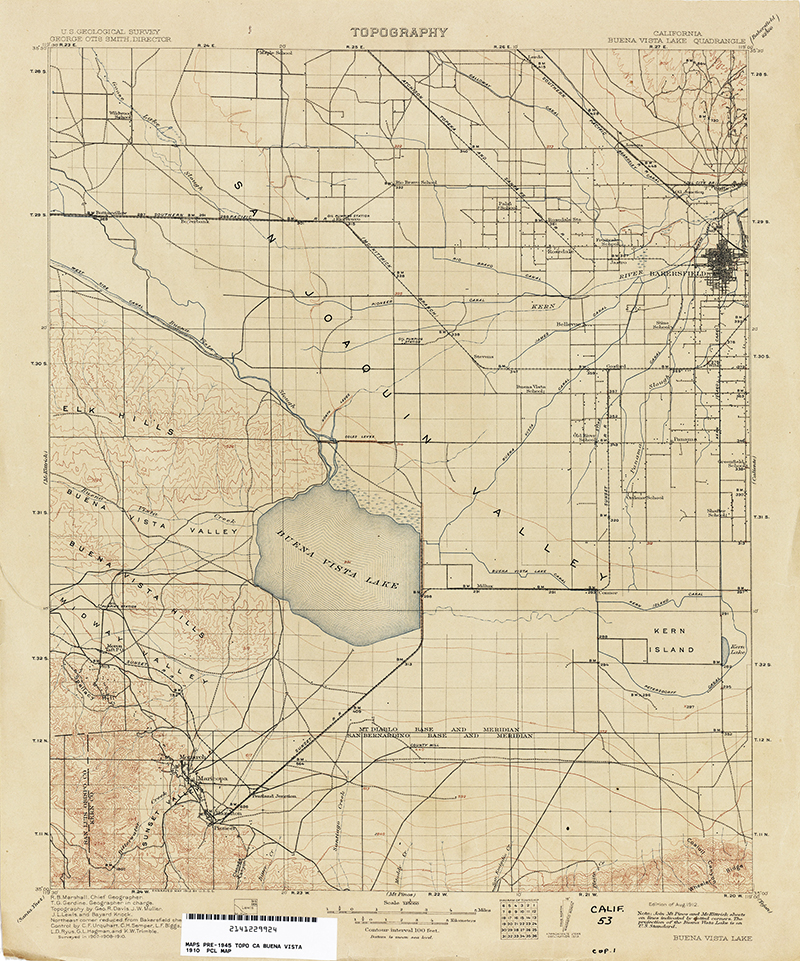

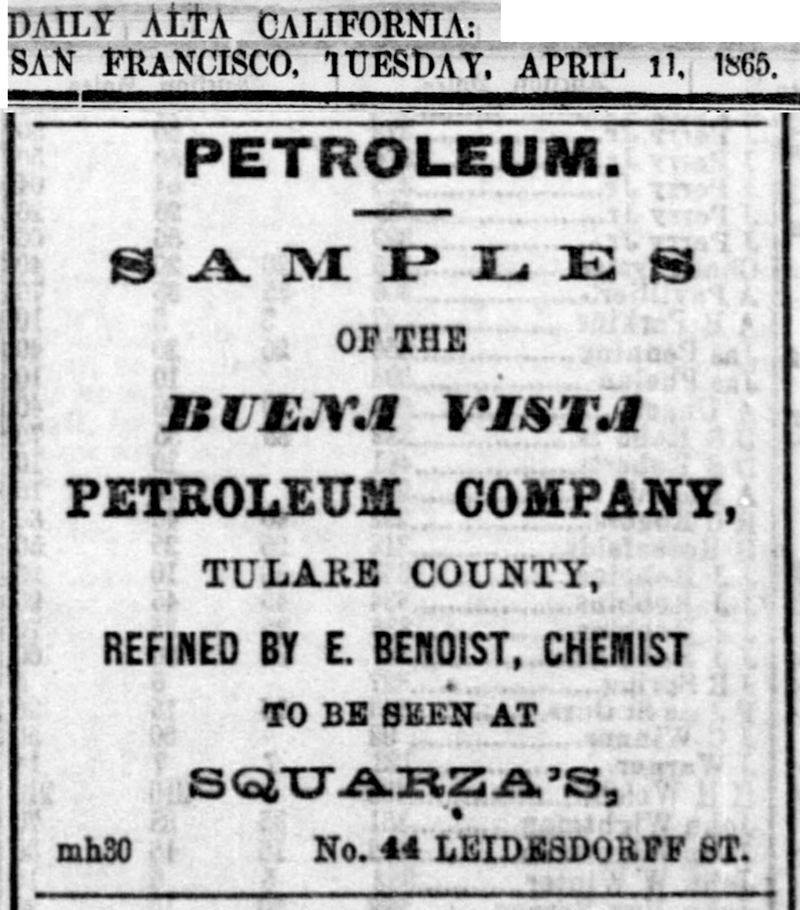

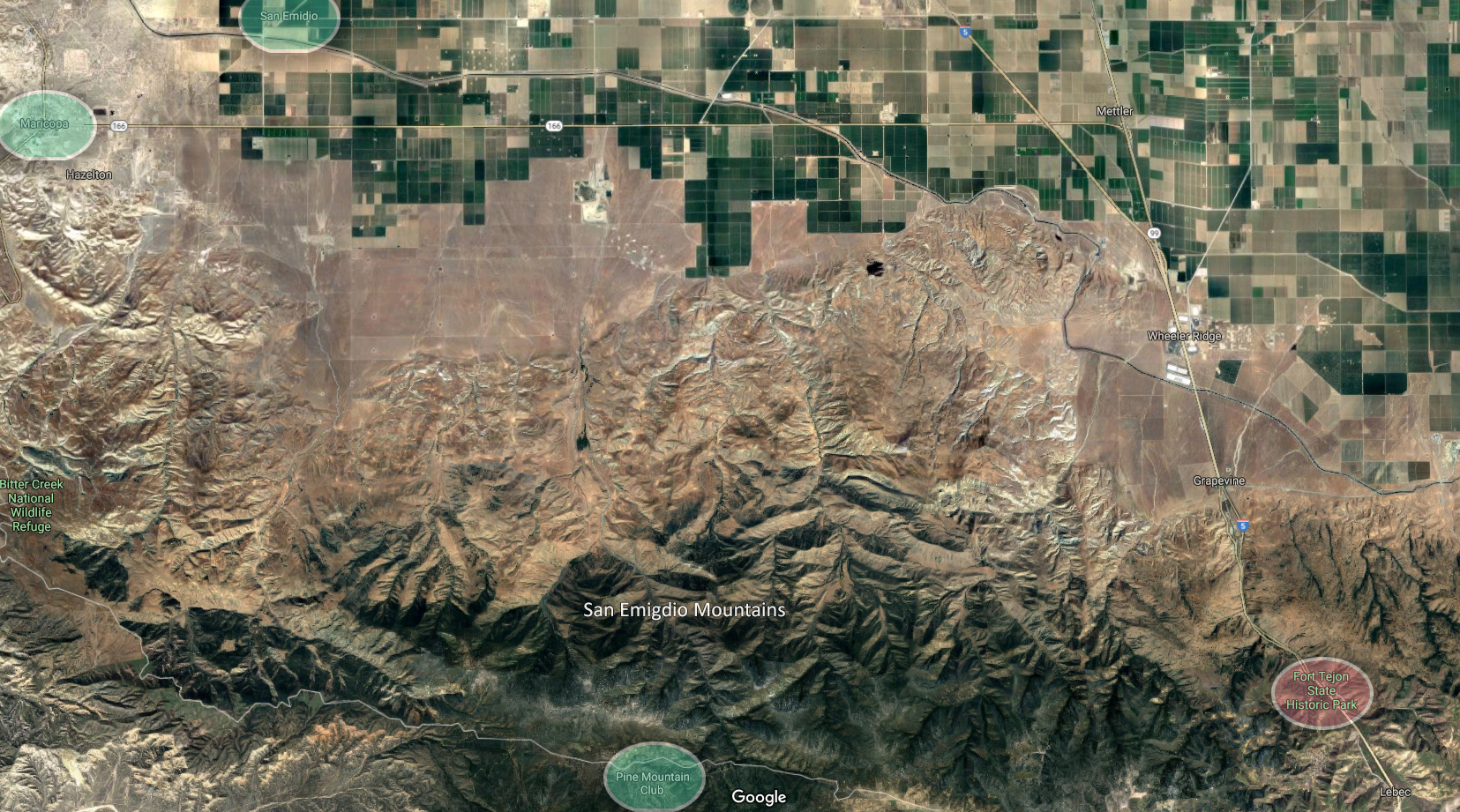

As for the location, San Emedio (one of several spellings of San Emigdio) is a mountain range in the southern foothills of the San Joaquin Valley, west-northwest of Fort Tejon. The fort was active from 1854-1864. At the time (1860s), San Emigdio was primarily a silver mining region. Buena Vista Lake was a natural lake which, like Tulare Lake to the north, dried up with the arrival of American farmers in the latter half of the 19th Century. (Today a relatively small portion of Buena Vista lake is the subject of a restoration project.) The area was part of Tulare County until April 2, 1866, five months after our stock certificate was issued, when Kern County was created out of the southern half of Tulare County and portions of Los Angeles and San Bernardino counties. But wait a minute. 1865? How is that possible? Didn't the first commercial oil production occur 11 years later in Pico Canyon west of Newhall? Yes, and no. Early Production. Pico (and its attendant town of Mentryville) was the site of the state's first successful oil operations. "Success" required transportation to market. Earlier in the same month that Charles Alexander Mentry began producing marketable quantities of petroleum at Pico (September 1876), the Southern Pacific line connecting Los Angeles (and Newhall) with the rest of the country was completed. The railroad enabled the shipping of Mentry's oil to resellers in San Francisco. It was an advantage the oil-rich San Joaquin Valley didn't have. Long-distance oil pipelines came a bit later. Mentry certainly wasn't the first to dig up black gold in California. Even in the Santa Clarita Valley, pioneers such as Sanford Lyon, Henry Clay Wiley and William W. Jenkins were extracting small quantities of petroleum in Pico Canyon the late 1860s. And more than a decade earlier, in 1856, the ex-Mexican Army General Andres Pico, the canyon's namesake, was gathering up oil from natural seepages, distilling it and using it to illuminate his home — the ex-Mission San Fernando[1]. No sooner did California become a state in 1850 than the hunt was on, in both north and south. One of the earliest oil drilling operations was set up in 1860 near the present MacArthur Park in Los Angeles, just east of the La Brea tar pits. A 400-gallon still produced 2,350 gallons of distillate, or 56 barrels, in five months. It was shipped (by ship) to San Francisco where it was further refined into kerosene.[2] By comparison, 16 years later, Alex Mentry would produce as much in two days from just one of several wells. But the name of the Los Angeles operator in 1860 makes us wonder. He was George H. Gilbert, a onetime whale-oil refiner. Could he be related to our Edward Gilbert, president of the San Emedio Petroleum Company? We don't know. Major Haskell.

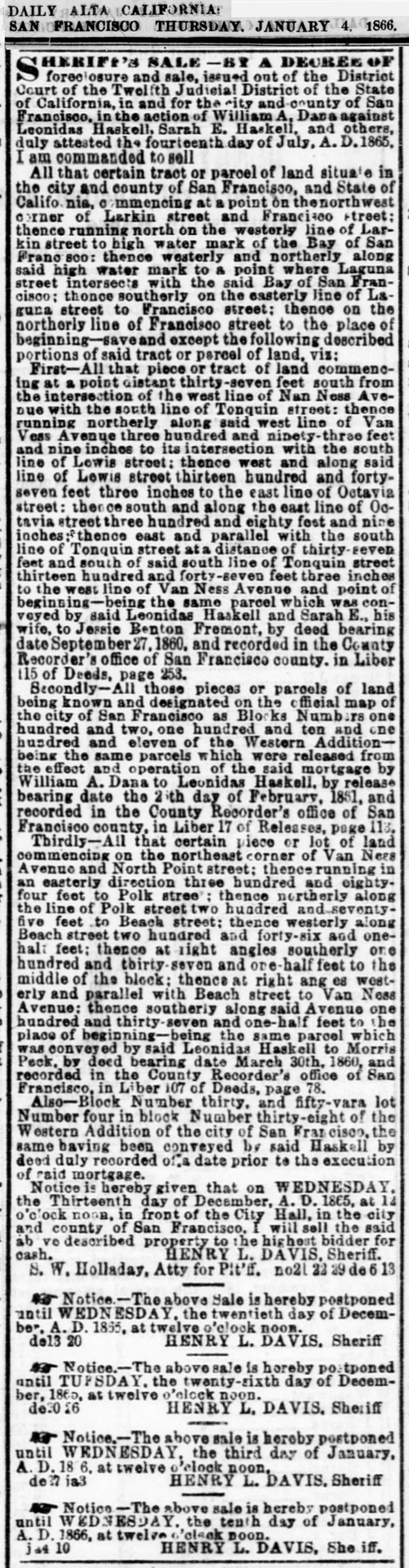

As indicated, we can't seem to pin down Edward Gilbert, but Leonidas Haskell is someone we can track. Born in December 1823 in Gloucester, Mass., he was working out of New York as a shipper of wool and hides[8] when he arrived at San Francisco in 1848[9]. He became a major landowner there. Much of what we know about him comes from reports of him being sued (in California) numerous times for nonperformance — although the reports took an odd twist in 1859 when a duel on the peninsula turned deadly and the loser, U.S. Sen. David C. Broderick, a Free Soil (anti-slavery) Democrat, died two days later at Haskell's house at the future Fort Mason, which is now part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area[10]. Haskell also owned racehorses (at least one)[11]. According to a biographer, he had a penchant for get-rich-quick schemes[12], so the speculative oil venture fits. In 1861, Haskell was listed as a California committee member to raise funds for the Union Army[13]. In 1862, back in Gloucester, he connected with John C. Fremont and served as Fremont's aide-de-camp following the Pathfinder's defeat at the hands of Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson at Cross Keys in Virginia. (Fremont had been the only Union general to win a battle in the year 1861.) Haskell traveled with Fremont during the latter's brief tenure as commander of the Western Armies; when Fremont resigned his Army commission later in 1862, Haskell rejoined his wife, Sarah Elizabeth Haskell (1827-1918), and their young children in New York for a time[14]. Before the war, Haskell had conveyed some of his San Francisco Bay property to Fremont's wife, Jessie. In 1863, the commanding general at San Francisco seized it and erected a battery there. At war's end, everybody went to court and to Washington, D.C., to sort out their property ownership disputes. In July 1865, about the same time Haskell was organizing the San Emedio Petroleum Company, all of his San Francisco property went into foreclosure — a big swath of the city around Van Ness Avenue that included the land he sold in 1860 to Jessie Benton Fremont — which the Fremonts in turn rented to Edward Fitzgerald Beale[15]. Haskell's property was set for a sheriff's sale in early 1866[16], although the final outcome of the foreclosure proceeding is unclear. One thing for sure is that the battery was built. Haskell wasn't done with Fremont. They engaged in all manner of crazy business schemes together and even convinced the Costa Rican government to let them build a railroad to export coffee — even though neither man had the money to do such a thing[17]. No way would Jessie ever make them a loan. Major Leonidas Haskell contracted malaria and spinal meningitis during the Civil War Battle of Cross Keys in June 1862. By 1867, he was essentially incapacitated. He was 49 when he died in Washington, D.C., on January 15, 1873. The United States Congress eventually agreed to compensate the former landowners for the wartime confiscation — far too late for Leonidas Haskell. — Leon Worden, 2019

1. Early California Oil, pg. 4. 2. Ibid., pg. 5. 3. Sacramento Daily Union, September 10, 1864. The Union gave the location as Mariposa County (Yosemite area). We suppose it is possible the company was incorporated there or had other workings there, considering its activites were frequently reported in the Mariposa Gazette — but its operations were in the vicinity of Buena Vista Lake at the eastern end of the future McKittrick oil field. There is a town named Maricopa (not Mariposa) in the area; perhaps this was a source of confusion. We don't know. 4. Ibid., January 7, 1865. 5. Red Bluff Independent, February 6, 1865. 6. Sacramento Daily Union, January 6, 1869. 7. Early California Oil, pg. 7. The Mariposa Gazette reported May 25, 1867, that the sale of Buena Vista Petroleum Company stock had been postponed. 8. California Farmer and Journal of Useful Sciences, November 4, 1859. The journal identifies him as "Leonidas Haskell, Esq.," which may or may not have meant he was an attorney. 9. Sacramento Daily Union, August 19, 1864. The report reads: "In the case of J.C. Daggett against Leonidas Haskell, an action for $5,745.32 damages, under terms of a contract for charter of ship Lucas in 1848, judgment is given for the plaintiff." 10. Mill Valley Record, August 25, 1923. Recollections of a pioneer. 11. Sacramento Daily Union, September 29, 1860. 12. "Haskell, Leonidas," by Stephanie Buck, 2015. Fitz Henry Lane (blog), a project of Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass. 13. Sacramento Daily Union, July 15, 1861. 14. Stephanie Buck, ibid. 15. Report No. 898, United States Senate, July 9, 1892. Report "to accompany S.3311, entitled a bill to refer the claim of Jessie Benton Fremont to certain land, and the improvements thereon, in San Francisco, Cal., to the Court of Claims." Beale reference at page 7. Published in "Reports of Committees of the Senate of the United States for the First Session of the Fifty-Second Congress, 1891-92." 16. Daily Alta California, January 4, 1866. 17. Stephanie Buck, ibid.

LW3623: 9600 dpi jpeg from original stock certificate purchased 2019 by Leon Worden (Holabird Americana, Lot 1816, May 16, 2019); ex-Ken Prag American Stock Certificate Collection.

|