Webmaster's note.

In the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society's September 2013 newsletter, Hart Museum employee Rachel Barnes poses the question: "Whatever happened to Richard and Ina Ito?" The Itos were

William S. Hart's domestic employees at his mansion in Newhall. There was no record of what became of them after the United States' entry into World War II in December 1941.

(According to local legend, Hart secured some sort of special dispensation for them. It turns out, local legend is incorrect.)

The answer to Barnes' question came in September 2019 from the Itos' son, Jason S. Ito, of Northridge, Calif., who had seen her article on the Historical Society website.

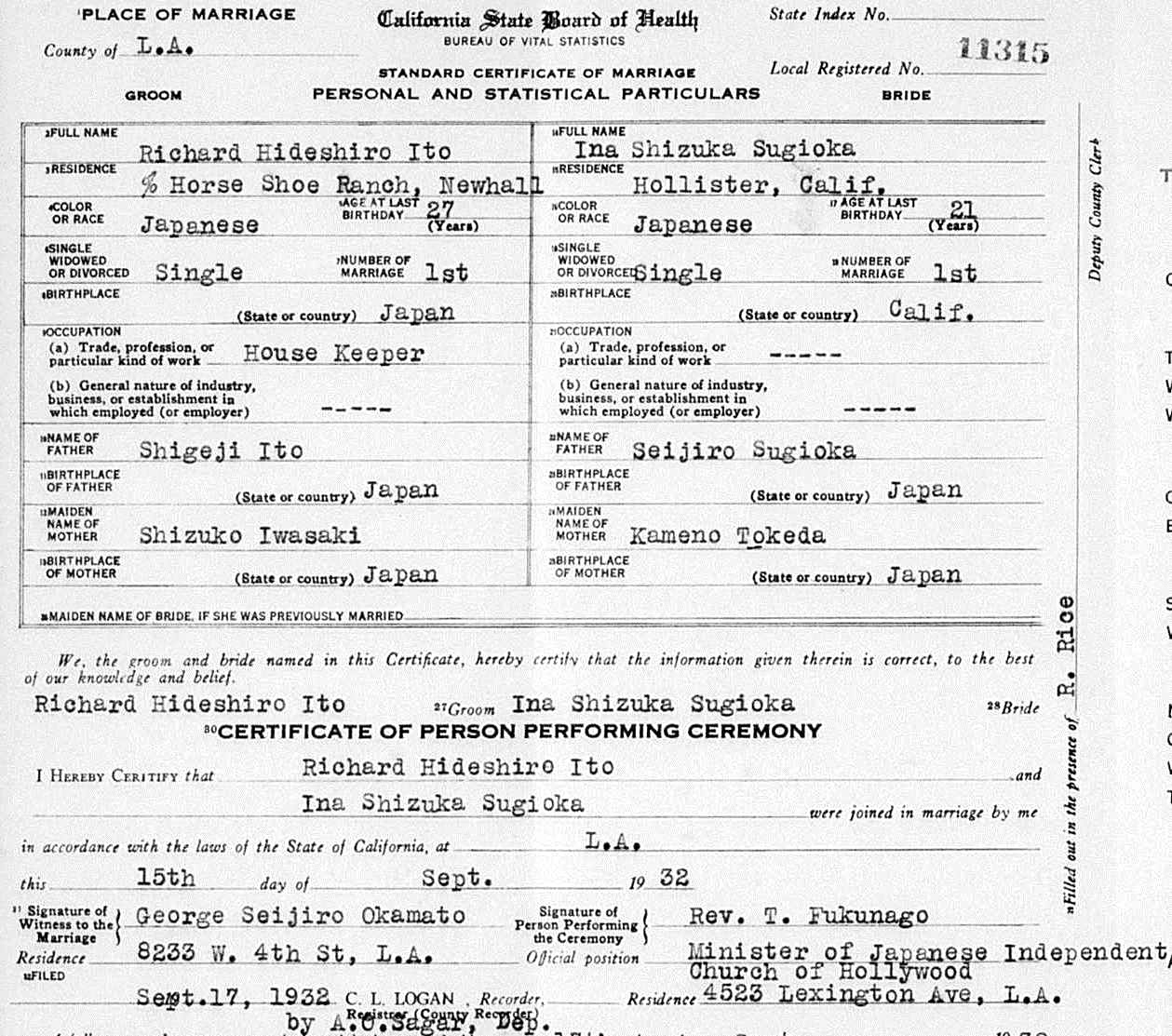

Jason Ito's father, Richard "Dick" Hideshiro Ito, was born November 25, 1906,

in Tokyo. Jason's mother, Ina Shizuka Sugioka, was one of 10 children of Japanese immigrants Seijiro and Kameno Sugioka. Ina was born June 24, 1911, in Hollister, California. Richard and Ina married September 15, 1932,

at the Japanese Independent Church of Hollywood.

In 1942, the Itos were removed to Camp Amache, aka Granada Relocation Center, in Colorado. Jason Ito picks up the story from there (inset).

Both my parents were interned at the Amache Colorado Relocation Center in 1942. In late 1942, they were granted a special permit to leave the Center, and the following year they obtained a

permanent permit which exempted them from the Center.

During that time, they worked for a photographer (a Mr. Knodel, full name unknown) in Rocky Ford, Colo. In late 1943, they moved to Denver and lived there until 1947 when they returned to

Los Angeles.

My father opened the Richard Ito Photography Studio in April 1948, with my mother assisting him off and on over the years he was in business. In early 1949, my mother worked for Art Originals

of California and worked there until 1954. My father received the Master of Photography designation August 10, 1960, the highest certification awarded by the Professional Photographers Association

of America.

I came along in 1961, and during my early years, my mother stayed home as a homemaker. Once I entered high school in the 1970s and beyond, my mother went to work for, among others,

Robinson's Department Store and the California State Department of Health & Human Services in Hollywood.

Both my parents were members of the Centenary United Methodist Church in Los Angeles. My mother passed away in September 1987, and my father deceased December 1993.

|

Whatever happened to Richard and Ina Ito? That is a question Hart Museum staff and volunteers ask themselves every day, and we are asked every day by our guests. Bill Hart's longtime employees — the only two staff members we can definitively say lived in the mansion at the top of the hill — are also longtime mysteries. How did Hart meet them? How long did they work for Bill and his sister, Mary Ellen? And what did happen to them? Did they leave California before the United States' entry into World War II? Or were they relocated to a Japanese internment camp?

Whatever happened to Richard and Ina Ito? That is a question Hart Museum staff and volunteers ask themselves every day, and we are asked every day by our guests. Bill Hart's longtime employees — the only two staff members we can definitively say lived in the mansion at the top of the hill — are also longtime mysteries. How did Hart meet them? How long did they work for Bill and his sister, Mary Ellen? And what did happen to them? Did they leave California before the United States' entry into World War II? Or were they relocated to a Japanese internment camp?

These mysteries prompted the Hart Museum to host its first Open House on Wednesday, August 7, 2013. A self-guided day, our visitors were invited to wander through the mansion at their own pace and participate in a series of activities and crafts related to the history of Japanese Americans.

This history started in the late 1800s, when young Japanese men first started emigrating to the United States in search of jobs that paid better wages. These early immigrants had no intention or desire to stay; they wanted to work here in the States for maybe five years and then gather up the riches they accumulated and move back home. Of course, jobs building the railroad, mining for gold, farming the land, and serving as domestic help didn't pay quite as well as these young men hoped, and within 10 to 20 years, Japanese women arrived to join their husbands and fathers. Within a generation, two distinct "classes" of Japanese developed here in the United States: Issei (immigrants) and Nisei (born in the USA).

As more Japanese immigrated and more Japanese-American families developed, we also see the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment. Despite their attempts to "Americanize" — changing their diets, their religions, and even some of their cultural practices — Issei and Nisei were still victims of segregation and racism, and often viewed as threats by their non-Japanese neighbors. And when the 20th Century dawned, so too did anti-Asian and anti-Japanese federal legislation. Stricter (and discriminatory) immigration standards were put in place for the Chinese as early as 1882, but similar laws were to follow for other nationalities as well, including the disgraceful Immigration Act of 1924, which set immigration quotas at 2 percent of the nationality's population in the United States in 1890. In other words, if there were 10, 000 people of Japanese descent living in the US in 1890, then only 200 Japanese citizens would be granted entry to the United States per year after 1924.

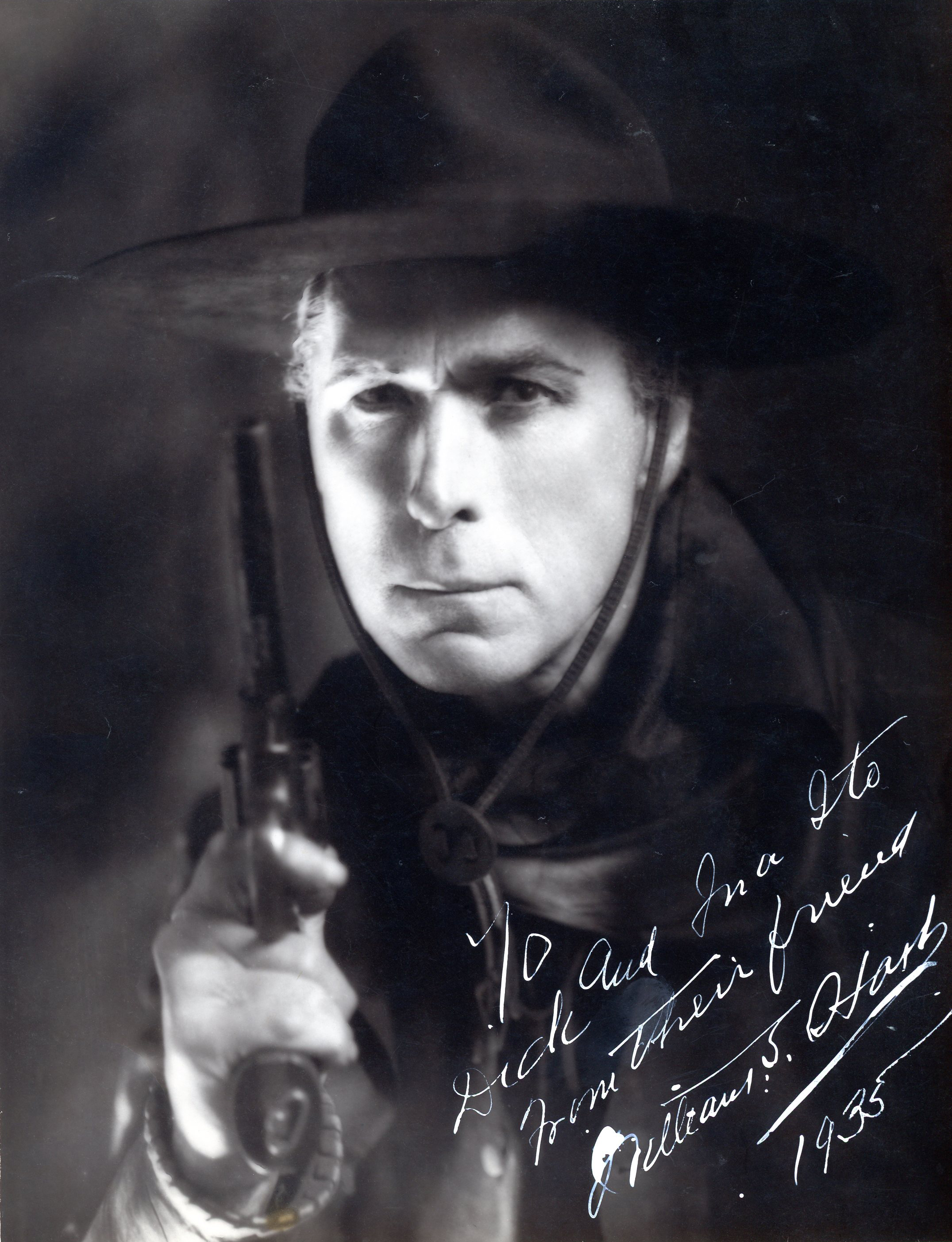

Photograph inscribed to Dick and Ina Ito by William S. Hart in 1935. Courtesy of Jason S. Ito (online only). Click to enlarge.

|

Then, in 1942, Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which established "military exclusion areas for people of Japanese ancestry" living in the western United States, and all Japanese and Japanese-Americans on this side of the country were forcibly removed from their homes to hastily established assembly centers. The U.S. military used fairgrounds and horse racetracks — Santa Anita was an assembly center — and the Japanese were forced to live in the stalls and barns while they waited for assignment to an internment camp. Anyone 17 and older had to complete a Loyalty Questionnaire, a form that tried to answer: Are you a loyal citizen of the United States? Or loyal to Japan?

The problem, however, lay in the way the questions on this survey were worded. No matter how people answered them, they were admitting to disloyalty, and on top of that, certain answers could mean, in the case of Japanese immigrants, the surrender of their Japanese citizenship, and thus the surrender of citizenship in any country (since they were not American citizens, either). It was a tricky and misleading format; admitting disloyalty meant assignment to a harsher concentration camp.

The tragedy continues, because even after release from the internment camps at the end of World War II, Japanese Americans still suffered ostracism and segregation. Restaurants would refuse to serve them, businesses refused to serve them, and many of their former properties were vandalized during the war. At the same time, Japanese culture thrived and prospered. Even though Japanese immigrants tried to Americanize, they also kept many of their cultural traditions alive. They tried to establish as normal a life as possible in the internment camps: Kids went to school, hospitals were established with Japanese doctors, traditions and holidays were celebrated, and incredible crafts were made from rubbish heaps.

So, while the mystery of what happened to the Itos remains unsolved, the Hart was very excited and thrilled to offer a day of special programming dedicated to their culture and history. Stay tuned because we will host our second Open House in December where we celebrate holidays from all around the world.

Click to enlarge.

|

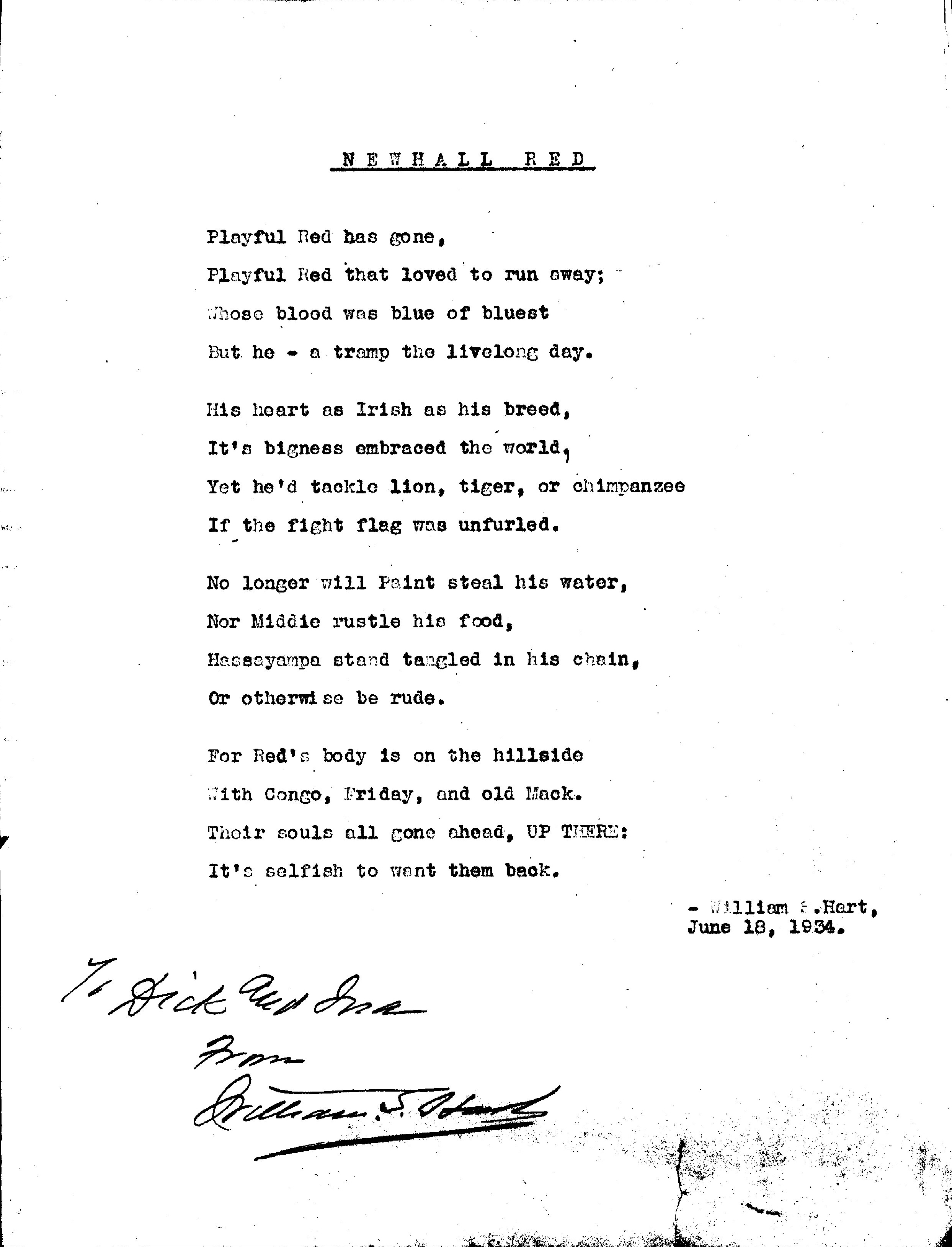

|

Inscribed "To Dick and Ina from William S. Hart"

June 18, 1934.

Courtesy of Jason S. Ito. (Online only.)

Playful Red has gone,

Playful Red that loved to run away;

Whose blood was blue of bluest

But he — a tramp the livelong day.

His heart as Irish as his breed,

It's bigness embraced the world,

Yet he'd tackle lion, tiger, or chimpanzee

If the fight flag was unfurled.

No longer will Paint steal his water,

Nor Middie rustle his food,

Hassayampa stand tangled in his chain,

Or otherwise be rude.

For Red's body is on the hillside

With Congo, Friday and old Mack.

Their souls all gone ahead, UP THERE:

It's selfish to want them back.

— William S. Hart,

June 18, 1934.

Red is buried in the dog cemetery at the ranch in Newhall. Photo: Hart collection/NHMLA. Click to enlarge.

|

|

Above: Richard and Ina Ito's 1932 marriage certificate (online only). Click to enlarge.

Above: Richard and Ina Ito's 1932 marriage certificate (online only). Click to enlarge.

Above: Richard and Ina Ito are buried at Green Hills Memorial Park in Rancho Palos Verdes. Photo courtesy of Jason S. Ito (online only). Click to enlarge.

Above: Richard and Ina Ito are buried at Green Hills Memorial Park in Rancho Palos Verdes. Photo courtesy of Jason S. Ito (online only). Click to enlarge.