|

|

Hart v. Hart Case File.

A Pyrrhic Victory for Winifred.

Los Angeles County Superior Court, 1924-1925.

|

"The people of the State of California send greetings to William S. Hart." "Gee, thanks."

By 1924, Winifred wasn't happy with the separation agreement she signed in 1922. Bill had set up trust accounts to support Winifred and their son, Bill Jr., as agreed, and for each of the first 18 months — plenty of time for the couple to secure a divorce — Winifred received $1,200. But she wouldn't divorce him, and as the 18-month window closed, her monthly payments dropped to $762.50 ($387.50 for her, $375 for Bill Jr.), just as the agreement stipulated. Winifred was accustomed to a higher lifstyle. She had been making $500 a week as a contract actress. Or so she told the court. Bill claimed she never earned more than $200 a week as an actress. Regardless, she wanted to act again. But she wasn't allowed. In February 1924 Winifred Westover Hart filed suit in Los Angeles County Superior Court to change the terms of the "property settlement agreement" she had signed May 12, 1922, two days after her formal separation from William S. Hart when he allegedly locked her — and her mother, Sophie — out of the house. (They were living in Hollywood, not at Bill's Newhall ranch.) We don't know much about Bill's side of things because he simply denied all of her allegations. Her allegations didn't affect the outcome, although the court held most of them to be true. Local legend and published news reports dictate that Winifred didn't get along with Bill's wheelchair-bound sister, Mary Ellen, who lived with him, and that his refusal to evict her drove the couple apart. But that's not directly addressed in the court file. Winifred testified that Bill sat her down at the kitchen table May 1, 1922, and told her their five-month-old marriage wasn't working. She claims he wanted her to divorce him so he could be free to remarry and have a family — just not with her. She refused. She told the court that divorce violated her beliefs and she didn't want her little son to gaze forlornly through the fence one day and see other children playing in Bill's yard. Bill Jr. was a toddler when the matter went to trial. He hadn't been born when Bill Sr. agreed in May 1922 to set aside $103,000 in trust for Winifred and another $100,000 for their unborn child. Under the terms of the property settlement agreement (the only "property" it covered were the trust funds), Winifred would receive payments until such time as their divorce was final, whereupon she would receive the balance of the money. Until then, Winifred would get a monthly check — but only if she gave up her acting career and became a full-time mother. Also, under the agreement, she couldn't use the Hart surname or connect his name to hers in any professional (presumably non-thespian) capacity. The agreement even included a morals clause — binding on her, not him. California courts have always frowned on "restraint of trade." Winifred claimed she didn't fully comprehend the settlement document the lawyers drafted, but it's evident that what swayed the judge is the fact that excluding someone from practicing his or her lawful profession tends to violate California public policy. The judge tossed out the "no acting" clause and ruled that the clause was severable, meaning the rest of the agreement stood as-is, meaning Bill had to continue paying her regardless of whether she acted again. Bill immediately appealed to the California Supreme Court. Three years later, in November 1928, without hearing oral arguments, the high court dismissed his appeal because by that time, it was moot. Winifred had finally agreed to a quickie divorce in Reno on February 11, 1927, and presumably got the remainder of the $203,000. In 1929, Winifred relaunched her acting career — not as the perky starlet she had been a decade earlier but as a serious actress. She hooked the leading role as the tragic hausfrau in the screen adaptation of Fannie Hurst's melancholy "Lummox" (released January 13, 1930, in Germany and January 18 in the United States). Winifred won rave reviews but lost at the box office and never acted again. Bill's relationship with his ex-wife and son was strained forever more. Bill Hart, who always dedicated his books, dedicated his 1929 autobiography to no one. He dedicated the 1933 first edition of "Hoofbeats" (among other things) to the son he rarely saw, but he changed the dedication to the memory of Mary Ellen (d. 1943) for the 1944 edition. In that same year (1944) Bill hammered out his last will and testament wherein he left his Hollywood house to the city of Los Angeles and his Newhall estate to the county of Los Angeles. That was how he reckoned he could leave his worldly possessions to the only people who never betrayed him — his loyal fans, who were still sending him letters every week. He assertively excluded his ex-wife and son from his will, saying the former had been "amply provided for under a property settlement agreement made in May of 1922" while the latter had received similiar support during Bill's lifetime.

Special thanks to historian Don Ray and The Endangered History Project Inc. for obtaining this copy of the Hart v. Hart case file from the Los Angeles County Hall of Records.

Download pdf here.

|

Hart's Siblings

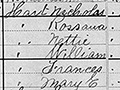

1880 Census (Hart)

Westover: Vital Stats

Westover ~1919 Hoover Art Co.

Westover in "Marked Men" 1919

Westover 1921

Westover in "Anne of Little Smoky" 1921

Mr. & Mrs. Hart

Lantern Slide

Wedding Effects & Baby Clothes

Bill Jr. Photos ~1940s

Separation 1922

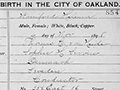

Bill Jr.'s Birth Cert. 1922

Westover's Father Accuses 1923

MacCaulley Paternity Swindle Part 1: 1923

• Fannye Bostic Pays a Visit 1923

Hart v. Hart 1924/25

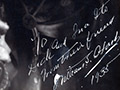

Westover by Spurr >1921

Westover in Court 1/1925

Westover ~1925

Mother & Son x2 ~1925

Mother & Son 1927

Letter Re: Son's Portrayal in 'My Life' 1929

Winifred Westover in "Lummox" 1930 (Mult.)

"Tumbleweeds" Lawsuit 1936-1939

Paternity Suit 1939

Complaint Against Dog Shooter 1940

Fate of Richard & Ina Ito, 1942 ff.

Sister's Death 1943

Sister's Probate 1944

Last Will & Testament of William S. Hart 1944

Westover Challenges Will 1950

Death Notice (AP): William S. Hart Jr. 1922-2004 Obituary (LAT): William S. Hart Jr. 1922-2004

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.