|

|

Ramon Perea: A Forgotten Name at Pico

By Leon Worden

Tuesday, Feb. 17, 2004

|

Every third grader in the Santa Clarita Valley learns the story while studying local history: In September 1876, a French-born oil driller named Charles Alexander Mentry deepened a well in Pico Canyon and struck "black gold." It was the first successful oil well west of Pennsylvania and gave rise to the state's first oil town (Mentryville). The oil was taken to Newhall where it was processed at the first productive oil refinery in the American West. But what was life like for the people who lived and worked in Mentryville? Where did they go to school? To church? To socialize? What did they do for recreation in the days before radio? And what prompted Alex Mentry to seek oil in this remote canyon in the first place? We've got a good picture of life in the bucolic, preindustrial Santa Clarita Valley, thanks to the personal histories that have been handed down from generation to generation. The Pico Canyon story is no different — except that no more than a handful of families were living there by the 1920s, so every bit of new information that's passed down is important. Last week the SCV Historical Society received a great gift from a former Newhall resident who now lives in Missouri, by the name of Merle E. Cook. His mother, Barbara Sitzman Cook, spent her formative years in Mentryville, moving there in 1927 at age 6 while her father, Charles Sitzman, ran the oil operations for the next decade. Barbara Cook held on to a treasure trove of memorabilia from her days in Pico Canyon, and now, after her death in 2002, her son boxed it up and shipped it "home" to Santa Clarita.

Hundreds of photographs and a hand-written log book from 1887-89, where Alex Mentry recorded his employees' hours, are priceless. But the gift is more than a collection of physical objects. Equally precious, if not more so, is the new information to be gleaned from that log book (who were the original workers?) and from school report cards (who were the teachers?), oil well production reports (how much was being pumped?), and photo captions (one in particular, indicating Newhall once had another name). A standout among the documentation is Barbara Sitzman Cook's own "story of Mentryville," which she probably first wrote as a grade-school student in the 1930s. I'm basing this guess on something the historical society received a year ago: a parallel "story of Mentryville" by one of Barbara's contemporaries, Nicolene Cheney, who also grew up in Mentryville in the 1920s and '30s. Evidently local history was part of the elementary school curriculum even then. Judging from the fact that Cheney wrote her Mentryville story by hand in a workbook while a child at Newhall Elementary School, it was a writing assignment, and the teachers used a standard version of the story which the students copied. What's notable is that both Sitzman and Cheney begin their stories with a name that isn't heard in the context of Mentryville anymore — Ramon Perea. Remember, Alex Mentry wasn't the first to arrive in Pico Canyon. He was the one who achieved success in 1876 where others had tried and failed in the 1860s — names we still know, like Sanford Lyon (Lyons Avenue), Henry Wiley (Wiley Canyon) and Bill Jenkins (later of Castaic). But according to Sitzman and Cheney's school reports, it was one Ramon Perea who, around 1855, hauled asphaltum — raw, tar-like oil seepages — out of the canyon and brought them to San Fernando, where they were analyzed by a chemist, Dr. Vincent Gelcich, whom the history books remember for understanding and trumpeting the riches that awaited in Pico. The late historian A.B. Perkins did make a reference to Perea (he spelled it Pereida) harvesting asphaltum in Pico Canyon, but subsequent historians have overlooked this man, instead attributing the 1855 "discovery" to Andres Pico and to Francisco Lopez (who found the first California gold in Placerita Canyon in 1842). It may be true that Pico and Lopez were also pulling asphaltum out of Pico Canyon in the 1850s and bringing it to San Fernando[1]. But the important person, apparently, to our early schoolteachers, was Perea. This should come as good news to some of his descendants. Scattered across the country, several have recently shared their family histories through the historical society's online archives at scvhistory.com. Now their claims about Ramon Perea as the "discoverer" at Pico are corroborated. (Of course, Tataviam Indians found and used asphaltum in Pico Canyon centuries earlier.)

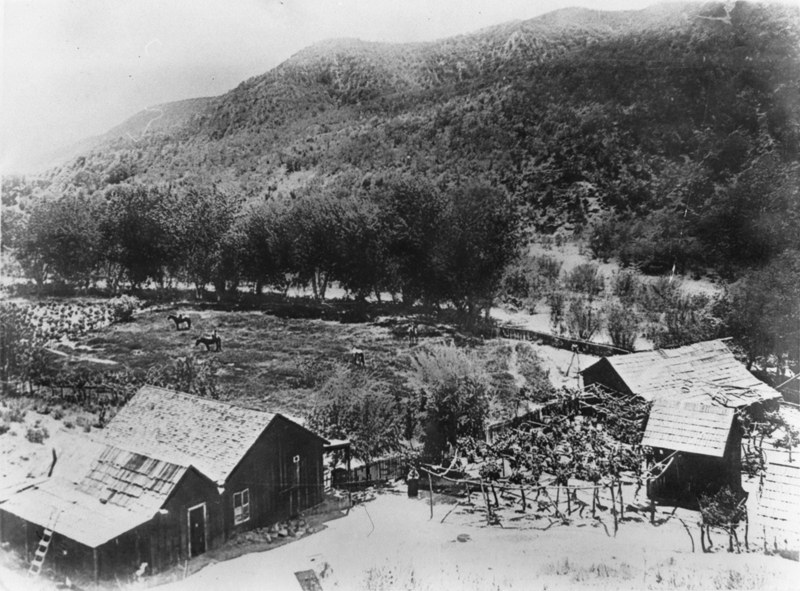

Who was Ramon Perea? We know he came from Mexico and, in the mid- to late 1800s, operated a vineyard at a ranch he owned in San Francisquito Canyon, just north of present-day Tesoro del Valle. Butterfield stagecoaches stopped at a station on the ranch in the 1850s and '60s. In the 1880s Perea sold the ranch to a family that is still represented in the canyon, the Raggios. According to one Perea descendant, the graveyard we know as the Ruiz Cemetery in San Francisquito Canyon was established by Ramon Perea when his wife died in 1888 at age 34. Indeed, Antonia Duran Perea's grave marker is the oldest in the family plot. A great-granddaughter writes: "Antonia asked him to bury her on the hill behind their ranch house in the San Francisquito Canyon, and he did. He said he put the cemetery high on the hill so in case there ever was a flood down the canyon, it would not wash the cemetery away." Prophetic words. The cemetery was at an elevation high enough to survive the St. Francis flood of 1928. Ramon Perea's own grave marker shows he was born Aug. 31, 1838, and died Jan. 25, 1915. Further Investigation Ramon Perea's involvement in Pico Canyon is noted in "Formative Years of the Far West," the history of the Standard Oil Company of California, by Gerald T. White (Meredith Publishing Co., 1962). Perea, by this account, may have been the initial "discoverer" while working as a cowboy (vaquero) for the Picos — Andres, who lived at the former Mission San Fernando, and Andres' son Romulo, who operated the family's 2,000-acre cattle ranch near the mission. "The Picos had learned of the (petroleum) spring from (Jesus) Hernandez (another vaquero) and Perea, who, according to one colorful account, stumbled upon it while on a hunting trip." Romulo rushed to file a claim on Jan. 24, 1865, for a "Naptha Spring in Petroleum ravine" approximately three miles from the mouth of Pico Canyon — evidently to the chagrin of Perea and Hernandez. "Romulo's hurried action in filing for what soon became known as Pico Springs, without any recompense to the vaqueros, aroused their resentment," White writes. Romulo filed the claim under California's Possessory Act of 1852, which was designed to keep order on public lands (Pico Canyon was U.S. government-owned property, situated between the Ranchos San Fernando and San Francisco) and to protect the rights of the first persons to arrive. Citizens could homestead 160 "clearly bounded" acres under the act and had to spend at least $200 to improve the property. But the act was intended to protect farming and ranching rights, not to convey mineral rights. These were sorted out in 1865 with the formation of mining districts. First, in March, came the Los Angeles Asphaltum and Petroleum Mining District, and a claim was filed on the Pico Springs. The identity of the "discoverer" is lost. "As insurance, many, if not most, of those who had homesteaded under the Possessory Act also put their claims on the books of the mining districts," White writes. "The claim to Pico Springs was recorded with the Los Angeles district on March 22 (1865), though the names of the six locators, including the 'discoverer' necessary to hold the 160 acres have been lost along with the records of the district. Romulo and Andres Pico were undoubtedly listed, and perhaps H.C. Wiley (A. Pico's son-in-law); the names of Hernandez and Perea, apparently, were also recorded." Hernandez was still mad at the Picos. According to White's account, Hernandez hired a lawyer and planned to file a claim to Pico Springs himself, "as the owner and occupant in actual possession" under the 1852 Possessory Act, and was prepared to sell the rights "to anyone who would buy" except the Picos. Two famous speculators, Gen. Edward F. Beale and Col. Robert S. Baker, took advantage of the dispute. They convinced Romulo to agree to a plan where they'd buy out Perea and Hernandez and split the claim evenly with the Picos. Hernandez and Perea filed on May 22 at Los Angeles; they immediately sold their rights to Baker for $300. On Aug. 8, Beale, Baker, Pio Pico (Andres' brother), Juan Forster (Andres' brother-in-law), Francisco Forster (Andres' nephew) and Sanford Lyon refiled the claim with the San Fernando Petroleum Mining District, which had been formed in June when the oilmen of the Santa Susana Mountains withdrew from the Los Angeles district. 1. Maybe. The idea that Pico was hauling asphaltum out of "his" canyon in the 1850s is tenuous at best. Read this.

©2004 LEON WORDEN — ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

Perea-Ruiz Cemetery

Perea in Pico:

Story (2000): Perea in San Francisquito

Raggio Ranch ~1940s

Raggio Ranch ~1940s

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.