|

|

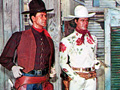

Flanking Flagg's 1922 painting of Fritz, Michael Kirk, auction manager for Nate D. Sanders Auctions (left) and Leon Worden of the Friends of Hart Park and Museum mimic the pose struck by Flagg and

Hart (sort of) when Flagg delivered his painting of the actor in 1924.

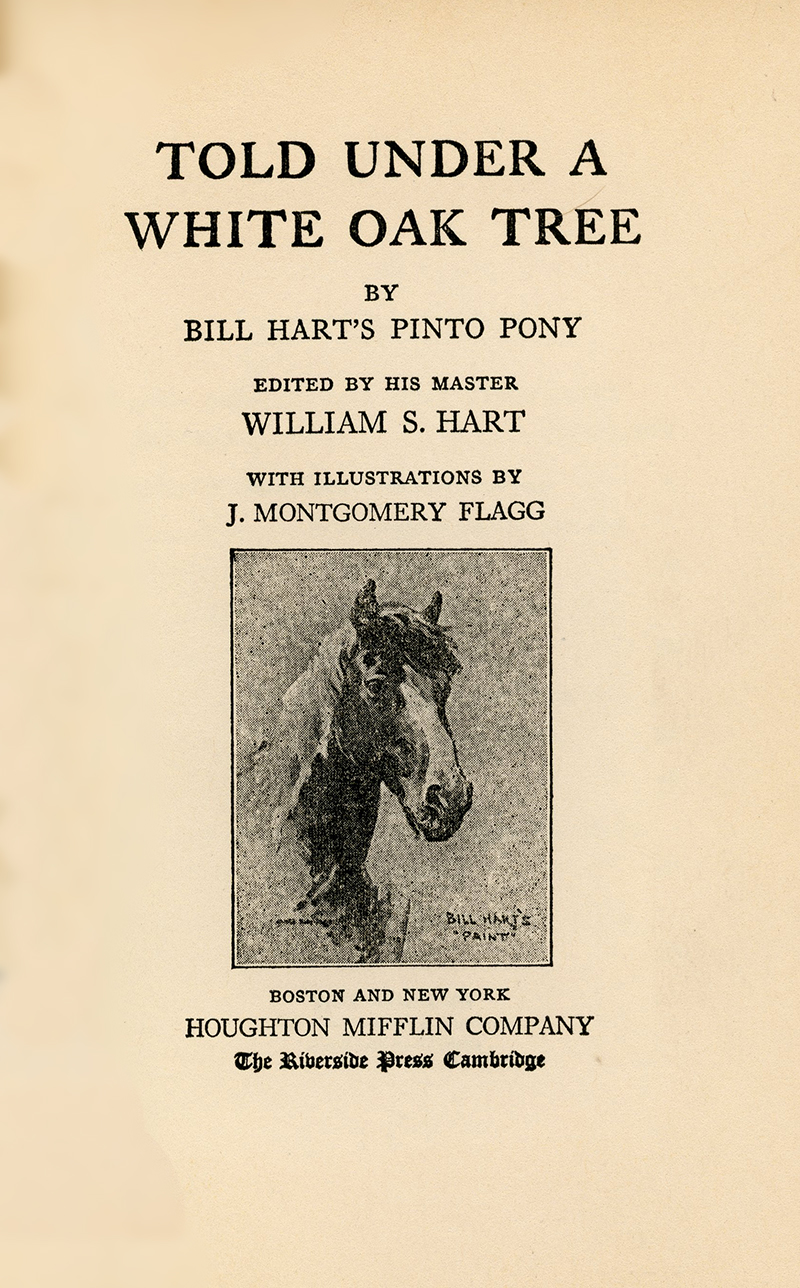

June 29, 2018 — James Montgomery Flagg's portrait of William S. Hart's favorite little paint horse, Fritz, has come home to Newhall following an absence of more than 90 years. Its existence was unknown locally before 2018. The original 21x30-inch oil-on-canvas painting (27x36 inches framed) had been in the possession of Hart's ex-wife, Winifred Westover, and their son, William S. Hart Jr. The undated portrait was completed during or before 1922, when it was used to illustrate the title page of one of Hart's books, "Told Under a White Oak Tree," copyrighted and published in that year. It is a children's book written in the voice of Fritz, wherein the talented horse takes credit for his master's many feats of derring-do. Flagg (1877-1960), a magazine illustrator (Saturday Evening Post, Collier's, Scribner's, etc.), is best known for his World War I army recruitment poster showing Uncle Sam pointing his finger at the viewer with the words, "I WANT YOU." A prolific painter and caricaturist who was pulling down $75,000 a year in the late 1890s — as a 20-year-old artist! — Flagg created a painting a day for years and illustrated five of Hart's books, mostly Western novels, from the 1920s-1940s. Flagg's painted-on title of this work, "Bill Hart's 'Paint,'" is consistent with the name the artist used for the animal in his 1946 autobiography, "Roses and Buckshot" (opposite page 113). But that is not the horse's proper name. "Paint" is a breed of horse that usually has pinto coloring. (Most paints are pintos, but not all pintos are paints.) Exactly how and when Westover and her son obtained the painting is unknown. One day after his 57th birthday in December 1921, Hart married the pretty, blonde, 22-year-old starlet at his home in (now West) Hollywood. Destined to fail, the union was over within months, and they were dividing up assets in divorce court before spring was out. In his will, drafted in 1944, Hart mentions a "property settlement agreement" that the couple executed May 12, 1922, two days after their marriage officially ended. (The divorce wasn't final until 1925.) But the only "property" contemplated in the May 1922 agreement was $203,000 in alimony and child support that Hart placed into trust, to wit: $103,000 for Westover and $100,000 for their unborn child. Westover did not receive the Flagg painting at this time. Come September 1922, exactly nine months after their wedding night, Westover gave "Two-Gun Bill" a son. It's plausible that Bill Jr. removed the paining from his father's Newhall mansion in 1946, during the brief period he served as executor of his father's estate. The county of Los Angeles, being the primary beneficiary, obtained relief from the court to replace the executor and preserve its assets. The resulting court battle between the county, on the one hand, and Westover and Bill Hart Jr., on the other, stretched out over the next decade. Westover and Bill Jr. lived in the Los Angeles area until Westover's death in 1978 and Bill Jr.'s retirement in 1989. Bill Jr. then moved to Bainbridge Island in Puget Sound off the coast of Seattle. He was hospitalized and died in the latter city in 2004. (His widow remarried and is still living in northwestern Washington state at this writing.) Following Bill Jr.'s death, the movie memorabilia he had kept from his parents' careers was sold in an estate sale or auction. None of the items came to the Santa Clarita Valley and were presumed to have scattered to the four winds. As it turns out, they didn't scatter far, and many didn't scatter at all. In May 2018, the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society was contacted by Aimee Howe of Inland Northwest Estate Sales in Spokane and alerted to some leftover William S. Hart material that didn't sell in a May 19-20 estate sale in the rural community of Pateros, Wash., about 110 air miles east of Seattle.

The identity of the estate owner was not disclosed, but it was a Western collector of memorabilia from Hart, Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, Clayton Moore (The Lone Ranger) and others, as well as taxidermy animals, guitars and other "cowboy" items. It's conjecture, but it seems likely the collector purchased the Hart material as an intact grouping following Bill Jr.'s death 14 years earlier. Among the Hart items in the 2018 sale were miscellaneous letters to Westover, a handwritten notebook by Westover, various autographed studio portraits of William S. Hart, an embroidered sash that incorporated photos of Hart, leather-bound travel kits, and a 1946 letter to Hart from his friend Rudy Vallee. Also: a copy of Hart's 1919 novel, "Pinto Ben" (which is really based on Fritz), inscribed "For Winifred from Bill;" and two copies of the 1994 Lakeside Press edition of Hart's biography that was published in cooperation with the Friends of Hart Park and Museum. The standout of the sale, by many orders of magnitude, was the Flagg painting of Fritz, which Howe consigned to Nate D. Sanders Auctions of Santa Monica. Bidding closed June 28, and the artwork was retrieved and brought back to Newhall June 29. Said Laurene Weste, mayor of Santa Clarita and president of the Friends of Hart Park and Museum: "I think it is a miraculous gift to have a 100-year-old piece of local history by a world-famous artist come back into our community so it can be loved, appreciated and cherished."

LW3322: Artwork purchased 2018 by Leon Worden. See file for notes.

|

Flagg: Fritz 1922

Flagg's KisselKar 1924

Flagg Presents Portrait 1924

Flagg Writes About Hart 1925

Letter 1926: Flagg Dissatisfied with Portrait

Letter from Hart to Flagg 1945

Charles M. Russell Portrait 1908

Flagg: Fritz 1922

Flagg Presents Portrait 1924

Flagg Writes About Hart 1925

Letter 1926: Flagg Dissatisfied with Portrait

Russian Sheet Music 1926

Billings Statue 1927 Mult.

Wax Museum 1962

Italian Star Card 1971

City Hall 2000

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.