|

|

The Walker Family of Placerita Canyon

Placerita Canyon Nature Center Associates, 2002 (Rev. 2012)

|

When the 12 Walker children were growing up in Placerita Canyon, they probably didn't realize the role they played as their lives became a chapter in Santa Clarita Valley's history book. Their heritage is the link between Placerita Canyon's early pioneers and the history lessons we teach to children who visit Placerita Canyon Park today. The "Walker clan," as the children were called, was born between 1909 and 1928 to Frank Evans Walker and Hortense Victoria (Reynier) Walker. With the marriage of Frank and Hortense, branches of two local family trees became intertwined. However, before we follow the branches, we must first explore their roots, which depict stories of courageous homesteaders. Much of the information in this report has been derived from personal interviews of Frank and Hortense's daughter Melba, and of two of her children George Starbuck IV and Gayle Starbuck. Additional information was provided by accounts from Frank Walker's diary, family ledgers, The Signal newspaper and the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society via SCVHistory.com. Although there were slight discrepancies in some dates, every effort was made to record the information as accurately as possible. Reynier Family Roots We start with the Reynier family (pronounced ren-YAY — ed.) in the Southern Alps of France. Jean Joseph Reynier, Hortense's father, was born March 30, 1849, into a large family of farmers. He had eight brothers and only one sister (some accounts report only four brothers). Due to crop failures and a great deal of civil unrest in the Champsaur Valley, 15-year-old Jean Joeseph embarked on a new adventure with his brother, Jean Mattieu, looking for opportunities in America. They set sail for New York with Mattieu's wife, Marie, with a final destination of San Francisco where they would join another brother, Jean Jacques. (Note: All Reynier brothers were given the first name of Jean.) Several years later, Joseph and Mattieu set out for Southern California with grape cuttings they'd brought from France, and with a herd of sheep. Although Mattieu decided to settle in Los Angeles, Joseph continued on, as he had heard about homesteading opportunities in the Placerita Canyon area. (Note: Like Pico Canyon, Placerita Canyon lay outside the boundaries of the San Francisco and San Fernando ranchos — ed.) Joseph finally arrived to his near home at the head of Placerita, near Sand Canyon. Joseph homesteaded 600 acres of land [sic: 487.65 ares] and built a Victorian-style ranch house. He became a farmer, raising sheep, growing olive and fruit trees, along with wine grapes — his French heritage. As he acquired more land, eventually 1,200 acres were planted with grape vines from the cuttings carefully brought from their French homeland.[1] The grapes were used for winemaking, Joseph's primary source of income. His great grandchildren are still growing cuttings from these vines. In 1882, Joseph married Josephine Sambien, originally from Switzerland. She gave birth to three children: Josephine, who married Charles Fisher; Joseph P.E., who never married; and Hortense Victoria (born 1866), who married Frank Evans Walker. After Josephine's death in 1896, Joseph married his first cousin, Della Seismat, in 1901.[2] Della brought to the marriage a daughter, Euginia, from a previous marriage. Joseph and Della had twins; it is unclear whether both died in infancy, or one died and the other survived to age 19.[3] With marriage and the birth of each child, Joseph was able to add acreage to his homestead. After five years of homesteading land, he owned the property outright. In this way, Joseph was able to acquire quite a bit of acreage — some say in the neighborhood of 2,400 acres. Each of his grandchildren inherited a portion of the homestead. All his life, Joseph spoke mostly French. He did learn to speak Spanish fluently, but his English was always broken. His grandchildren loved to visit, as he was a generous and affectionate man. As he was somewhat well-to-do, his home sported all the modern conveniences of the day. Joseph died on his birthday, March 30, 1936, at age 87. His beautiful home stood until sometime in the 1950s. Walker Family Roots Frank Evans Walker was born Feb. 12, 1886, in Springfield, Ill., to William Raymond Walker and Rosa Belle (Evans) Walker. Little is known about William's ancestry. Rosa Belle, whose portrait still hangs above the fireplace in the cabin near the Placerita Nature Center, was the daughter of James G. Evans and Mary M. (Cool) Evans. Records indicate Frank's parents resided somewhere in Los Angeles but had mining interests in Placerita Canyon, which can probably be attributed to Frank's material grandfather, James Evans. In 1885, James Evans became acquainted with a placer miner. Placerita derives its name from these mines; "placerita" is Spanish for "little mine." Evans reached Placerita Canyon by wagon over the Old Spanish Trail, which passed through or near Beale's Cut; it was just a rough dirt trail in those days. Frank's grandfather brought up quite a few placer mines in the Placerita Canyon area. In 1894 when Frank was 8 years old, he first came to Newhall with his grandfather. He would stay in the miners' camp, located on the flat area that is currently Placerita Canyon Park, for two or three weeks during school vacation. Frank's grandfather leased some land to an oil company in 1898. In 1900 they hit a gusher of pure white oil — a unique geological occurrence.[4] It was quite a sight, spewing oil 60 to 90 feet in the air for about three months. Oil was said to have run down the canyon and creeks, reaching as far as Saugus. (We would consider this a major environmental disaster.) This discovery of oil, containing a low grade of gasoline, also seeped natural gas. Anyone hiking up the canyon can still see where the oil was discovered: The spot is still "bubbling" as natural gas continues to seep. Other companies came in and tried to drill nearby. Had they drilled just a bit deeper and farther west, they would have hit the narrow Placerita Fault, which became the rich Placerita Oil Field.[5] James Evans had acquired his land by filing a patent on a mining claim, which conveyed title to the property. At the time, when a person purchased a mining claim, after so many years the owner could convert the land to private property. James gave his daughter, Rosa Bells, land and mining claims as a gift when she married William Walker. After a long, hard life as a pioneer and miner, James died in 1907 at age 73. Rosa Belle died in 1910 at age 51. Her mother, Mary, died in 1911 at age 75. Walker Homestead

Frank Walker moved permanently to Placerita Canyon in 1905 at age 19 and homesteaded "a stone's throw from where the first gold was discovered," as he liked to say. He initially acquired some land from his grandfather to get started, then inherited more when Evans died. For $10 an acre — a total $2,000 — he purchased 200 acres from the Newhall Community (Presbyterian) Church, which was the first church in Newhall. Frank met Hortense Reynier, who was living on a neighboring ranch. He would see her riding by on a little horse-drawn cart, followed by her pet sheep. They began to court, riding horses together all over the canyon. With their marriage in 1908, Frank's homestead grew even larger with the addition of land given to them by Hortense's father, Joseph, following the custom of the day. The land Rosa Belle received from her father was eventually passed down to her son Frank upon her death in 1910; by this time, Frank was married with two children. This portion of the Walker property was later sold to the Mitchell family of Soledad Canyon, although the Mitchells never used it as their home. They either ran cattle on the land themselves, or leased it to ranchers who ran cattle.[6] This accounts for much of the history of the property until about 1980, other than the fact that the Walker kids (and their children) used it as their personal playground. Currently (2002) this area is the site of the planned community of Golden Valley Ranch. Frank built several homes throughout Placerita Canyon, all with his own hands. The remains of one of these homes can still be seen in the canyon. The first cabin, which is always referred to as "the homestead," was built around 1908. Its stone columns and foundation still stand just yards north of Placerita Canyon Road. The family lived in this home until it burned down around 1918.[7] The family built its second cabin down in the canyon along the present-day Heritage Trail near the Nature Center. Park visitors can tour the cabin and see the present restoration with furnishings, tools and other items that are representative of life in the early 1900s, including a large dining table built by Frank Walker. With simple board-and-batten construction, the cabin had a main room with a fireplace and the parents' bedroom off to one side. Originally it had a tarpaper roof, two sleeping areas for the kids on the back side of the cabin, as well as some storage — all of which have been removed. The porch is not part of the original construction; a film crew added it at a later date. Although the firewood came from the trees on the property — chopped down using a huge, two-person handsaw — the lumber used in construction came from the town lumber store. It would have been too difficult to make the 2"x12" boards that were needed; plus, redwood was used, and redwood is not native to the area. It lasts much longer than native timber and can still be seen on the cabin. It is difficult to imagine a family with 12 children living in this small cabin. According to Melba Fisher, just six of the children lived there; birth records suggest at least seven of the 12 were living there, and eventually all of the children would be born during the time the family occupied this home.[8] The kitchen was located outdoors at the back of the cabin where all of the cooking took place on a wood-burning stove. Even though Newhall was becoming modernized, the Walker homes never had electricity, indoor plumbing or running toilets. Due to the effort it required to prepare, baths were taking only once per week. A large galvanized tub had to be filled with water hauled in buckets and heated on the stove. Family members took turns, sharing the same bath water. Water was hauled from Placerita Creek for everything, until about 1924 when Frank dug a well and fitted it with a hand pump. The pump still had to be primed, so a bucket of creek water still had to be kept nearby to prime it. Around 1929, a third cabin was constructed two miles up the canyon where it was much cooler in the summer, in what is now known as the Walker Ranch section of the park. At this point the Walkers had two homes: a winter cabin (previously described) and a summer cabin (immediately east of the present-day junction of the Canyon, Los Pinetos and Waterfall trails in the park — ed.) There were three or four creeks that had to be crossed between the two cabins. Winter rains would flood the creeks and wash out the dirt road along the main streambed. Thus, during the winter, the family lived in the accessible "winter" cabin. The kids could walk to the main road to catch their school bus, and Frank could drive his Model T into town for supplies. When the rains disappeared, the family spent most of the year at the summer cabin. Although it contained just two rooms, this cabin was much larger, with a living room and a big kitchen (with a sink) that ran the entire length of one wall. It had a covered porch, surrounded by half-walls. Separate sleeping cabins were built nearby: one for Frank and Hortense, and several others for the children. Up the canyon was a natural spring. Frank was able to bring water down the canyon by constructing a pipeline to make a reservoir. He also connected a pipe to the sink, but as it did not have an on-off handle, the water ran all the time. Frank also invented a device he called an oil-gas-water separator that was placed over the white oil well. The invention allowed the Walkers to direct the oil to a storage drum, while routing the natural gas to a pipe that went straight to the stove in the cabin's kitchen. Gas flowed freely from the stove, so to prevent a buildup of excess gas and possible explosion, beans were always cooking in a large graniteware pot and coffee was constantly brewing.[9] The mangle lamps also used this gas, so the lights were never turned off completely. Melba and the grandchildren spoke often of how the cabin smelled: a mixture of strong coffee, refried beans and gas or oil. Any one of these scents still triggers a flood of memories for family members. Frank Walker's story is a tale of constant building. The cabins and other areas of the property were always a work in progress. The concrete floors in the cabin were added one section at a time. Each house was continually worked on and upgraded. The entire family built a permanent road from the winter cabin up to the summer cabin by hand. This new road allowed them to live year-‘round at the Walker Ranch. Melba laughingly remembers that her father never finished a project. While that may have been the perception, historical evidence tells us he completed at least some of his undertakings. One project that was not finished was the fourth Walker cabin. The foundation was poured and a gorgeous "fancy rock" fireplace was built. Melba recalls with sadness that the cabin was never completed because her mother died before it could be finished. The year was 1932 — just four years after Hortense gave birth to her last child. The Walker family did move to a fourth home — a boarding house in Redondo Beach that enabled Frank to get help raising his young children. Several years later the family moved back to the Walker Ranch and the older children helped raise the younger ones.[10] The Walker Ranch summer cabin was torn down to make room for a campground after the state of California purchased the property for a park. When hiking up to the waterfall, one can still see the flat area near the stone fireplace, which still stands. This flat area is the spot where the summer cabin once stood. Walker Family Life We return now to the early days of Frank and Hortense's marriage and review the daily life of the Walker clan. The first child, Irene, was born in 1909. Another sibling followed her every year or two until there were an even dozen: five girls and seven boys. The last child was Richard, born in 1928. Melba Walker, from whom much of the information in this report is derived, was the sixth child, born in 1916. A neighbor called "Mama Bello" was Hortense's midwife for the first of the children, including Melba, whom she cared for as a baby. In later years, when the family moved to the winter cabin, a doctor with a big, black bag would come to the house. Melba always thought the baby came to them in this bag because the doctor would disappear into Hortense's bedroom and reappear with a tiny baby in his arms.[11] The children have memories of a hard life. Money seemed scarce. According to Melba, everyone got a pair of shoes once a year if they were lucky. Most of the time the kids walked around barefoot. Their clothing consisted of hand-me-downs that were passed along from one child to the next, patched and ill-fitting. The kids at school called them the "poor Walker kids." About six of the Walker kids went to school in Newhall at any one time. They would walk to the main road to catch the school bus, which was really just a 1927 Chevrolet with a sign on the front and back that read, "School Bus." Their father wasn't particularly keen on formal education, so most of the children attended school only through the sixth or seventh grade.[12] During their "off" time, the siblings were expected to do their chores and help their father with any number of his money-making projects. They had a natural spring for water; deer were plentiful, and they raised beef and dairy cattle, pigs, chickens and horses. They also grew potatoes, green onions and some carrots. Melba remembers performing many chores including chopping wood, milking cows and carrying water. Charles always managed to bring home many deer to eat, somehow avoiding the game warden (shooting deer was frowned upon). The kids had to be careful because bears, foxes, bobcats, mountain lions and rattlesnakes were as abundant as the deer. Frank collected a bounty of $20 for every mountain lion he shot. Melba talked about catching a fox and keeping it as a pet for a while. Christmas was a wonderful time for the Walker clan. They got to eat a big, roasted turkey that their mother had prepared with black sage, which grew all over the canyon. Santa was generous with his gift. The stockings always held and apple, an orange, two or three walnuts, and a red rubber ball for the little ones. The older boys received a pick and the girls got a shovel.[13] Downtown Newhall was a modern town with a drug store, grocery store, gas station, post office and lumber store. Townsfolk enjoyed all of the modern conveniences including electricity, sewage treatment and indoor plumbing. The children loved to visit their Aunt Josie (Josephine Reynier Fisher) in Newhall or their relatives in Los Angeles because they "had everything" and "life was better," Melba remembers.[14] Occasionally the family would take the train to Los Angeles. Sometimes they drove down in the Model T, but most roads weren't paved, so the trip was long and arduous. Melba spoke of a bustling city of two-story buildings and the May Company department store. She recalls with regret that the time always came to go home and return to a more primitive way of life. Resentment seemed evident when any of the children spoke of growing up this way. Most of the kids left home when fairly young, usually in their teens, and sometimes in the dark of night. Melba left home at 18 and Charles, then just 16, left the same year. There was a long period of grief and tragedy in the Walker household as the family lost members in 1929 (Helen), 1930 (Clarence), 1932 (Hortense) and 1935 (Frances). The three children died young; Helen died at 17 from some type of heart ailment, while Clarence succumbed to tuberculosis at 20. The death of Frances was a huge scandal.[15] It appears she was involved in a love triangle. According to reports in the weekly Newhall Signal newspaper, on April 13, 1935, Frances was shot and killed by Gladys Carter, the wife of Newhall Sheriff's Deputy A.C. Carter, at a cabin on the property of a Dr. Mackey in Placerita Canyon; Gladys Carter then turned the gun on herself but the wound wasn't fatal. (Note: According to the Los Angeles Times, the killing occurred April 1; April 13 was the date Gladys Carter was convicted of manslaughter.) A.C. Carter admitted to the affair during his wife's trial. (Read the full story here.) On a lighter note, there's a story the Walker descendants love to tell. The dates don't necessarily work, but it sounds probable and most likely involved Hortense's father, Joseph Reynier. Hortense hadn't come along in 1873 and Josphine didn't marry Joseph until 1882, but I recite the story as told to me so the facts can be sorted out later with further research. They tell a story of the notorious outlaw Tiburcio Vasquez passing through the Reynier property as he traveled the trail from the San Fernando Valley north to hideout in present-day Vasquez Canyon. As the story goes, in 1873 Vasquez arrived one night and woke up the family by banging his shotgun on the porch. He demanded lots of food and then bed. Melba said her mother reportedly fixed half a dozen eggs, plus six or seven thick slabs of bacon. This was an enormous amount of food for a large family to spare. Vasquez warned them, "Don't wake me up! I wake up with a gun in my hand." He visited several times after that, and the routine never varied. Despite his appearance and his reputation, the family recalls he was always a charming, polite gentleman. He left a $5 gold piece under the plate every time for Hortense to find later. Vasquez's story ends as most bandit stories do, with his capture in 1874 and hanging in 1875. Frank Walker was quite the entrepreneur and had numerous profitable projects throughout his lifetime. Probably the source of income that first comes to mind is gold prospecting; ironically, panning for gold never made the family much money. Sometimes, Frank found enough gold to earn about $22 in one day, [16] but there were many days he would find nothing. The raw gold was shipped periodically to San Fernando, so it was imperative that a safe hiding place be found for the gold to be stored between shipments. A family album unveiled a 1907 photo of Hortense, taken prior to her marriage to Frank, standing next to a bluff. A hand-written caption reads, "Hole where the gold was hid."[17] This hole, which was originally a prospecting tunnel, can be seen today on the right-hand side of the hiking trail, approximately halfway to the Walker Ranch end of the park. Frank eventually found a way to make gold prospecting more profitable. A lot of city people wanted to come to Placerita and experience gold prospecting. In the 1930s, Frank started Walker's Gold Panning Camp (aka Walker's Placerita Camp). Admission to the park was 25 cents per person, per day, and included parking, a picnic table and stove, gold panning privileges and recreation. Visitors could rent a completely furnished cabin, housekeeping included, for $1.25 per person, per day. If one preferred to make a stay of it, weekly rates ranged from $8 to $20 depending on size and location, and could accommodate two to six persons. Barbecue dinners cold be specially prepared for parties of 10 or more, if provided with four days' advance notice. This cost $1.25 per person and included the 25-cent admission charge. Visitors were treated to music, dancing and other entertainment. To make sure everyone went home happy and with a bag of gold, Frank would salt the sluice or the individual pans with his own gold. The project was well planned and quite profitable. Although he would use $30 to $40 in gold he had prospected himself, he would typically make two or three times that amount in admission fees and rentals.[18] Selling Placerita "fancy rock" also helped feed the Walker clan. All of the Walker cabins had fireplaces and stone columns built from this beautiful rock. Fancy rock — not the scientific name, which is schist, but simply the name given by the Walkers to the to the green and white colored rock — washed down from the hills. The kids would find the rocks in creek beds and load them onto the back of the truck to be taken into town. The fancy rock was sold to homeowners, primarily to build fireplaces. It has been said the Walkers raised a lot of chickens, not just for their eggs and consumption, but also to sell to others along with the fruits and vegetables they took to the market. Coyotes put an end to this idea fairly quickly. A well-kept secret until recent years is that Frank Walker was a bootlegger. He acquired any wine that his father-in-law, Joseph Reynier, didn't consider fine enough to sell, and distilled it into brandy. [19] At one time, three stills were hidden in areas up the canyon. The Walker kids kept vigil in strategic places, and if a stranger or a local deputy sheriff came too close, they would whistle to each other to signal those working the stills to shut them down and hide them.[20] Several flavors of brandy were made, including peach, and it is said that Frank made whiskey, as well. The bottles of liquor were taken to town, hidden under a load of fruit and vegetables. Frank Walker was caught selling whiskey only once, as far as the family knows. He left one night to sell liquor and didn't come home that night. A family member bailed him out for $50 and his bootlegging career continued without missing a beat.[21] On Saturday nights, the Walkers held dances so their friends and others from town could socialize, dance and secretly purchase brandy or whiskey. In addition to helping with the family budget, the dances were a welcome source of entertainment and a reprieve from the daily drudgery. The summer cabin supposedly held a dance floor, which was actually the cement foundation for the fourth cabin that was never completed. Hortense played the fiddle and guitar, and other musicians would come and play. The kids were not allowed to be out after 10 p.m., but they would watch from the windows. One night, the kids played a prank on an inebriated gentlemen when they tied the bumper of his Model T to a tree. The dance broke up around 2 p.m.; when he tried to leave, the wheels of his car just spun and kicked up dirt. Eventually someone came out with a pocket knife and cut him loose. Like other Depression-era families, Frank Walker couldn't afford to pay his children an allowance to do chores. They loved working for their grandfather because he would pay them $2 a week to pick and stomp grapes. Another money-making project was the cement block business. In their "off" time, the older kids used a hoe to mix cement in huge tubs. The cement was poured into molds to create blocks approximately 8"x16"x4" in size. There was a large building on Pine Street in Newhall that stored the cement blocks until they were sold. The last of the labor-intensive projects was the clay mine. Recollections of this project also bring to mind the numerous complaints voiced by the Walker clan. They were tired of the difficult physical labor. Clay had to be dug out of Sand Canyon, placed into bags and loaded onto flatbed trucks. The clay was taken to a company in Gardena that kiln-fired it and ground it into the red gravel and grit used in roofing. Ray Walker had enough of this life, so he threw down his pick and didn't come back to work or to his home.[22] Many of the children left like this, still in their teens. Sixteen-year-old Charles left in the middle of the night, catching a ride to Los Angeles. Usually they would return years later, after they were married with children of their own. One source of income that delighted the kids (and didn't include hard labor!) was renting the property or the cabins to movie companies. Many of the Westerns seen from the late 1920s to the 1940s used portions of the Walker property because it offered rugged, isolated countryside. The going rate for using the Walker Ranch in 1928 was $5 per day. The family ledgers show that Republic Studios rented the property on numerous occasions. The family would sometimes dine with the film crew, the older kids occasionally whipping up pancakes and eggs. Frank would make a couple of extra bucks for the use of certain items on the property. The winter cabin was altered by several film companies. The porch and a shingle roof were added, and the two back bedrooms were removed. The back side of the cabin sported a "Wells Fargo" façade to make it look like a stagecoach station. The front of the cabin was the setting for numerous gunfights. Sometimes the kids would be used as extras in the films, and this is likely how Clarence caught the acting bug. Surviving family members say Clarence can be seen in several Western films. He was just beginning what looked like a promising acting career when he died of tuberculosis in 1930. Frank lived in his cabin long after his children moved away, even continuing to live on the property after it was purchased in 1949 for $48,000 by the state of California to create Placerita Canyon Park.[23] In 1959, the state paid Walker another $150,000 for more property, expanding the park to its current 351 acres. Now Frank went to live with one of his sons, where he remained until his death in 1971 at age 85. Another Branch on the Family Tree Melba Walker met her husband while taking a walk. His name was George Starbuck III, and his family lived in neighboring Iron Canyon. They had two children, Gayle and George Starbuck IV. The Starbuck family history is another important piece of our valley's heritage. The family's American roots date to 1640 when their original Quaker ancestors settled on Nantucket Island. Their story is rich with anecdotes of working on whaling ships; their connection to the first mate in the story, "Moby Dick," who had an affinity for coffee; and living on Nantucket alongside families named Macy and Folgers. The Starbucks settled in the Santa Clarita Valley by 1880. Their story deserves to be told in detail, but that's a legacy for another day. Melba married again, becoming Melba Fisher. She had two more children with her second husband, Walt.[24] Melba (Walker) Starbuck Fisher had her children continue to keep the Walker history alive by giving lectures about the family to interested groups, granting interviews for newspaper articles and helping the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society by providing photographs and information. With their continued help and support, the Walker legacy lives on. Footnotes Webmaster's Note: Family histories are funny things. Most are based on experiences and memories. An older sibling may have had a very different experience from a younger sibling or relative, and as the stories are told and retold by different people through the years, they often diverge. The Walker family stories are no exception. After reviewing the original draft of the 2002 document you've just read — based to great degree on the memories of Melba (Walker) Fisher and her children, George and Gayle Starbuck — the Placerita Canyon Nature Center Associates received a set of notes from a great-grandson-in-law of Frank Walker in which the writer, Fred Salter, shared a different view of certain events from the perspective of other family members including his wife, Mary Helen Walker, who was the daughter of Thomas Glenn "Tommy" Walker, one of Frank Walker's sons. Prior to submittal, Salter said he also gathered input from more of Frank's sons — Frank Jr., Richard and Edward — and from several others including Melba, whose health was in decline. While it is to some degree the job of the historian to review conflicting versions of events and reconcile them, it does not seem appropriate to attempt that here. The subject matter is too narrow. We don't have benefit of sufficient disinterested sources or documentation. Instead, when an entry or incident is contested, we make note of it and present the conflicting information in the footnotes below, together with a few other remarks we believe relevant.

|

MORE PHOTOS:

SEE ALSO:

Video: Points of Interest with Melba Fisher, Raymond Walker, George Starbuck

Video 2002

Reynier Land Patent 1897

Rock Column House 1910s

7 Children, Late 1910s

Whole Family 1928

Family ~1930

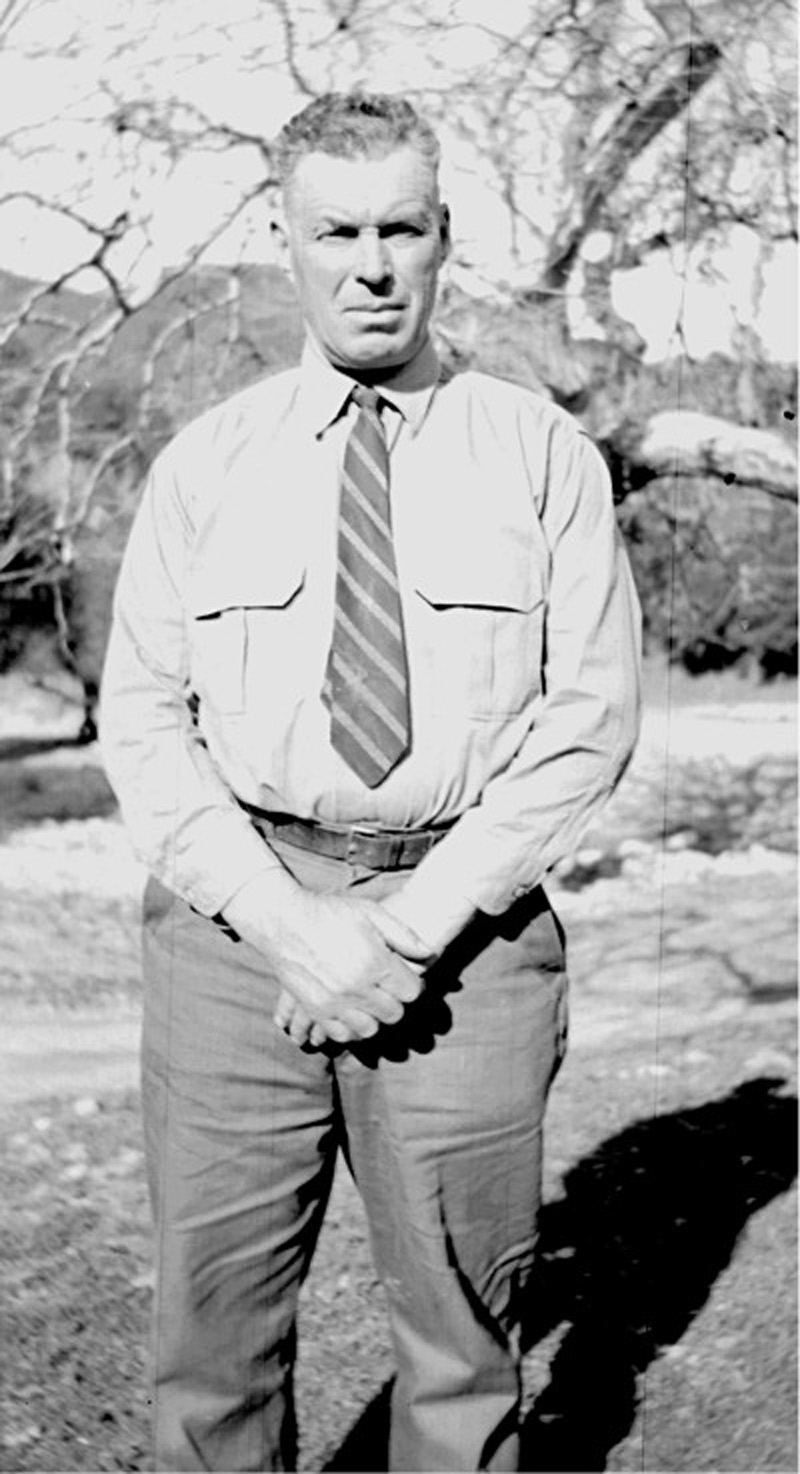

Frank Walker 1935

Frances Walker Slain 1935

Melba & Irene 1935

Melba Walker Fisher (Mult.)

Cher with Grandma Lynda Walker 1940s

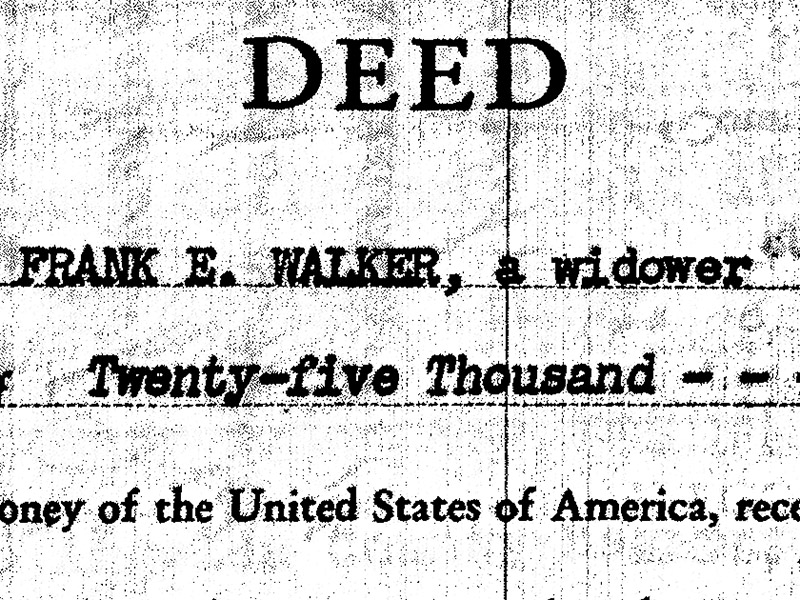

Deed to Park's First 40 Acres 1949

Truck, Tractor Donation 2022

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.