|

|

Wm. S. Hart Attends Sister's Probate Hearing

Personal Life of William S. Hart

Click image to enlarge

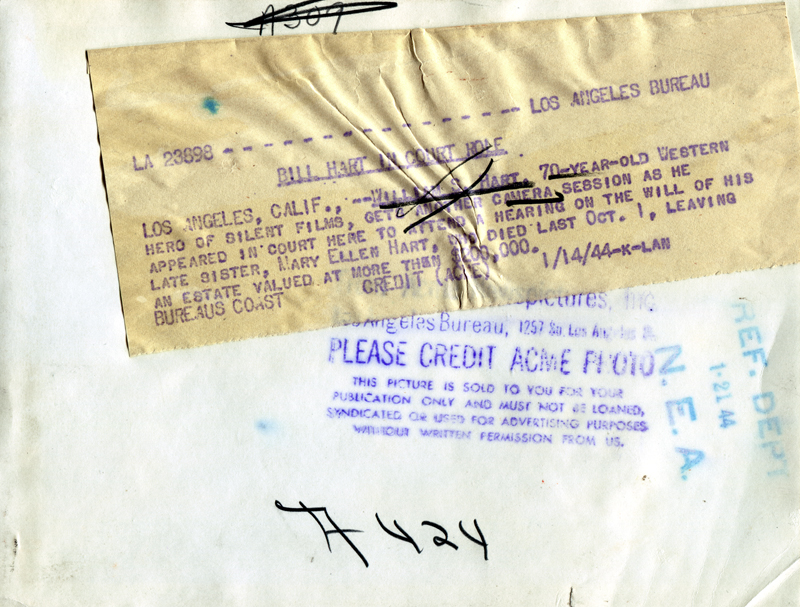

ACME wire photo (6"x8") of William S. Hart at the county courthouse in downtown Los Angeles following a Jan. 14, 1944, probate hearing on the $200,000-plus estate of his sister, Mary Ellen. She had lived at her brother's mansion in Newhall until her death on Oct. 1, 1943. Newspaper archive source unknown; print acquired in 2013 from a Hart collector in Lancashire, England. The print has been damaged, possibly by an acid splash, which appears as white splotches. AP cutline reads:

LA 23898 — — — LOS ANGELES BUREAU It should be noted that Hart probably wasn't 70. During his film career, which he started in his late 40s, he said he was born in December 1873 (in which case he would be 70 here). It is believed he was actually born in 1864 — but we can't know for sure because the birth records in his home town of Newburgh, N.Y., seem to have been lost to fire in the late 1800s.

Brief Union Silent film superstar William S. Hart appeared opposite the fetching Winifred Westover, 34 years his junior, in Lambert Hillyer's "John Petticoats" (1919). Two years later, on Dec. 7, 1921 — the day after his 57th birthday — Hart left bachelorhood behind and exchanged marital vows with the starlet at his home at 8341 De Longpre Ave. in present-day West Hollywood. Exactly nine months after their wedding night, on Sept. 6, 1922, the union produced a son, William S. Hart Jr. By that time the May-December romance was long over. The couple separated and spent the next several years in court. Hart devotes no more than a single paragraph to Westover and their issue in his 1929 autobiography, "My Life East and West." Most sources indicate the separation came after just three months; in "My Life," Hart says it was five months, and he provides the date: May 10, 1922. But May 10 was actually the date of a court appearance. The couple had already separated by May 10, when a judge in Los Angeles named C.W. Guerin (Gueren?) refused Hart's motion to stop Westover from fighting the terms of a separate maintenance agreement that barred her from ever again appearing in movies. In September 1922, just days after Bill Jr.'s birth, with divorce proceedings in full swing, Westover's attorney, Milton Cohen, tried to convince the court that Hart once ordered his wife from their home. The Los Angeles Times quoted Hart's retort in its Sept. 17 edition: "If Cohen claims I was physically cruel to my wife, I'll lick him so you won't be able to recognize him. If I can't do that, I'll drill a hole in his stomach so big you can drive a twenty-mule-team borax wagon through it." In "My Life," Hart says Westover sued him for divorce on grounds of desertion. Why the unnecessary and damning concession? Was he implying she couldn't have beat him on a cruelty charge? Or that she couldn't have accused him of infidelity? We don't know. But from his lasting friendships (see the Wyatt Earp letters, for instance) and the intense devotion he felt from his fans (to whom he left everything in the end), we know loyalty was a virtue he cherished — and rewarded. It stands to reason that disloyalty would earn you a swift kick out the door. On Feb. 11, 1927, nearly five years after the couple separated, the divorce became final in Reno, Nev. Around the same time, construction started on a 22-room hilltop mansion in Newhall that Hart began planning in 1926 as a retirement home for himself and his younger, wheelchair-bound sister, Mary Ellen. It was completed in late 1927. Life in a Fishbowl With the passage of time, we tend to forget that William S. Hart was a major Hollywood celebrity, and that then as now, Americans relied on daily newspapers and movie fanzines to slake their insatiable appetite for information about their favorite stars. The only difference is that today, the latest gossip circulates in the blink of any eye through the Internet and TV, and fresh fanzines hit the supermarket check-out counters weekly instead of monthly. Hart was no stranger to the courtroom — or to the cameras outside it, or to those that occasionally managed to follow him into it. Hart, like all others, paid the price of celebrity. He had a personal life but not a private one. It's axiomatic: If you want the publicity that compels people to watch what you want them to watch or read what you want them to read (or vote how you want them to vote), you forfeit the right to stop those same cameras from seeing what you don't necessarily want them to see. This is a crucial point. If we're to understand the profound fealty Hart felt for, and from, his fans, we must view it through the lens of a man whose fans remained true to him even as the press drew back the curtain. The shutters clicked as Hart's marriage unraveled, and they clicked again in 1936 when he took United Artists to court in New York City for breach of contract. He'd made his last film, "Tumbleweeds," eleven years earlier, and he accused the studio of failing to make good on an agreement to promote it. His insistence on "keeping it real," in today's vernacular, had been his undoing; up against newer, flashier Western stars such as Tom Mix and Hoot Gibson, Hart was told as early as 1921 to change his approach or hand over production to someone else. He refused, and Paramount Studios bid him adieu. By 1925, distributors had stopped giving his films as wide a release as the blockbusters of the day; ultimately he sued United Artists over it, seeking to recover the $500,000 in anticipated earnings he said he'd lost. Three years after their court date, in 1939, Astor Pictures Corp. re-released the film and tacked a new, 8-minute monologue onto it as an introduction. Filmed at Hart's Newhall estate, the "farewell" monologue was his only speaking role in a film and his last appearance on the big screen. The shutters clicked again on Aug. 20, 1939, when Hart finally quashed a bogus paternity suit that had haunted him for nearly 20 years. It temporarily interrupted his film career in the early 1920s and can't have helped his failing marriage. The shutters clicked many more times: when Hart's ex-wife sought to renegotiate her alimony; when Hart swore out a criminal complaint against a Newhall man who took potshots at a beloved Great Dane in 1940; and when his sister Mary Ellen was buried in 1943. At the end of William S. Hart's 81½-year life, where did things stand? His acting career had ended 21 years earlier and left him feeling betrayed by studio executives. The sister he cared for and lived with was gone, as were his oldest friends. The only intimate liaisons we know about were fleeting and fickle and provided years of misery. His pinto pony Fritz and many treasured pets rested beneath headstones at the base of a hill below a secluded mansion overlooking a town he rarely visited. The people in his life who hadn't disappointed him were his fans. (Well, except for the psycho stalker who accused him of fathering her child.) They wrote to him nearly every day, and he answered every letter and signed every autograph his fans requested every time he penned a new novel that took him on a mental jouney back to a country that existed the way he chose to remember it. The shutters didn't stop clicking when Hart died. Not by a longshot. Legacy Contested Born in Oakland on Nov. 9, 1898, and schooled by the Dominican Sisters of San Rafael, the blonde, blue-eyed, 5'3" Winifred Westover made her acting debut in D.W. Griffith's landmark film, "Intolerance" (1916). She earned screen credits until 1922, when she became a single mom; she attempted a comeback in 1930, reportedly with her ex-husband's help. But but the film, Herbert Brenon's adaptation of Fannie Hurst's popular novel, "Lummox," was a box-office flop, and she retired. (Unfortunately we can't judge it for ourselves, as it is a lost film.) Westover and Bill Jr. made their peace with Hart as he lay dying at California Luthern Hospital in Los Angeles, present at his bedside when he breathed his last on June 23, 1946. Soon, mother and son were back in court, the pair having been all but omitted from Hart's will. The actor left his Newhall retirement estate to the people of Los Angeles County (there was no city of Santa Clarita yet); two years earlier he had donated his home on De Longpre to the city of Los Angeles (there was no city of West Hollywood yet). He also gifted $50,000 in cash to each jurisdition so the properties could be properly maintained for the enduring enjoyment of his loyal fans. They weren't his only acts of public generosity. In 1940 he donated land and money for the Newhall American Legion to build the area'a first real movie theater where his films, and others', could be properly displayed. He donated more land and money for the construction of the Santa Clarita Valley's first high school — which the school board decided to name for him, as he learned shortly before his death. He explained his decision to donate his Los Angeles property in 1944: "I am only trying to do an act of justice. I am only trying to give back to the American public some part of what the American public has already given to me." Those who might have been closest to him, Westover and Bill Jr., received no similar justice, and their nearly decade-long attempt to right what they perceived as a wrong came to naught. Westover died March 19, 1978, in Los Angeles. William S. Hart Jr. became a teacher and real estate appraiser in Santa Monica. He retired in 1989, the same year the city of Los Angeles leased the De Longpre property to West Hollywood and transfered the balance of the endowment, now valued at $284,000, to the new city. Bill Jr. objected to the transfer and called for an accounting. Considering how little L.A. had spent to improve the property over the past four decades, by the son's calculations there should have been $800,000 in the bank. He wondered aloud where the money went, but his protestations fell on deaf ears. He died May 13, 2004, in Seattle. — Leon Worden, 2012

LW2318b: 9600 dpi jpeg from original print purchased 2013 by Leon Worden. |

Hart's Siblings

1880 Census (Hart)

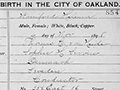

Westover: Vital Stats

Westover ~1919 Hoover Art Co.

Westover in "Marked Men" 1919

Westover 1921

Westover in "Anne of Little Smoky" 1921

Mr. & Mrs. Hart

Lantern Slide

Wedding Effects & Baby Clothes

Bill Jr. Photos ~1940s

Separation 1922

Bill Jr.'s Birth Cert. 1922

Westover's Father Accuses 1923

MacCaulley Paternity Swindle Part 1: 1923

• Fannye Bostic Pays a Visit 1923

Hart v. Hart 1924/25

Westover by Spurr >1921

Westover in Court 1/1925

Westover ~1925

Mother & Son x2 ~1925

Mother & Son 1927

Letter Re: Son's Portrayal in 'My Life' 1929

Winifred Westover in "Lummox" 1930 (Mult.)

"Tumbleweeds" Lawsuit 1936-1939

Paternity Suit 1939

Complaint Against Dog Shooter 1940

Fate of Richard & Ina Ito, 1942 ff.

Sister's Death 1943

Sister's Probate 1944

Last Will & Testament of William S. Hart 1944

Westover Challenges Will 1950

Death Notice (AP): William S. Hart Jr. 1922-2004 Obituary (LAT): William S. Hart Jr. 1922-2004

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.