|

|

Bowers Cave | Peabody Museum

One of four Tataviam sunsticks, aka sun staffs (perforated stone with handle), found in Bowers Cave in the San Martin Mountains (present-day Val Verde area) in 1884. In the collection of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. In 1952, the Peabody traded one of the four sunsticks (probably No. 39263) to the South Australian Museum in Adelaide, Australia. The remaining three are numbered 39261, 39262 and 39264. We're not exactly sure which one of the three this is, but it's probably No. 39261; it's consistent with the illustration in Plate 5d of Elsasser and Heizer (1963). It also appears to be the specimen shown in Fig. 15 of Henshaw (1887), which tells us the stick is 18 inches long. The four stones vary in diameter from 4.25 to 5.5 inches, and they are held in place with asphaltum. Their use was probably ceremonial. Elsasser and Heizer say the following about No. 39261: Material, igneous rock; the stone head is set off 10 degrees from the right angle which would be formed by the handle and the transverse plane of the stone; the small, transverse cuts (tallies?) mentioned by Henshaw are about 6mm long, spaced 5cm apart, and extend almost the total length of the haft; red ocher decoration now consists of 4 encircling bands abuot 8mm wide, 3 on the side of the stone and 1 on the distal end, concentric with the perforation; end of haft extends 17mm beyond the outer edge of central perforation.

Outside diameter of stone: 11.5cm Henshaw interpreted the sunsticks in 1887, three years after their discovery, for the Smithsonian, for whom Stephen Bowers collected California Indian specimens (although Bowers gave or sold the Bowers Cave specimens to the Peabody in 1885). The relevant section of Henshaw's paper appears below, followed by a discussion of the collection of Native Californian cultural materials and their dispersal to overseas musuems.

Perforated Stones from California (Exerpt: pp. 28-31)

Stones with handles.

In connection with the subject of ceremonial stones, attention may be drawn at this point to four unique specimens discovered by Dr. Stephen Bowers[1] in a cave in the San Martin Mountains, Los Angeles County, California, and described in Pacific Science Monthly, June, 1885. They are unique because they are the only perforated stones thus far found in the United States which are attached to handles. These specimens have been added to the collection of the Peabody Museum, and three of them are now before me for examination, through the courtesy of Professor Putnam[2], who has kindly permitted them to be figured for use in the present paper. As the accompanying figures (Figs. 14, 15, and 16) afford an excellent idea of their peculiarities, a brief description will suffice. The disks are of a kind frequently found in California, and, in themselves, are not especially noteworthy. They are made of moderately hard stone, from 4¼ to 5½ inches in diameter. The holes were probably made by first being pecked from either side and subsequently drilled, and, as is frequently the case, are made smaller at the center, presenting somewhat the shape of a double cone. All three of the stones retain plain traces of paint markings, which, as will be seen in the illustrations, are disposed in regular patterns. It is to be noticed that the edges of the stones are smooth and show no evidences of abrasion by blows or other rough usage, a fact not at all agreeing with the idea that they served for hammers of any kind. The handles are from 15 to 18 inches long, and are made apparently of rather tough wood. All three are natural branches, dressed only to the extent of removing the bark and paring off the twigs, so that the natural inequalities of the wood, the knots, &c., are plainly visible. They are smooth as though from the friction of much use. The handle of one (Fig. 16) is marked transversely by a series of cuts, disposed for the most part in regular rows, and presenting the appearance of tallies. A most interesting feature of these specimens is the method by which the heads are fastened to the handles, which is done by asphaltum, a mineral which abounds in many localities of Southern California and was much used by Indians for fastening, mending, &c. The sticks are thrust through the stones so as to project slightly beyond, and as the holes are much larger at the circumference than at the center, the handles, if set at right angles to the stone, would bear only upon the center. Under the circumstances it would perhaps be a rather nice matter to adjust and cement them at right angles; and, either from accident or from design, they are set at an acute angle to the base of the stones, the angle being greater in the specimen shown in Feb. 16 than in the others. The unoccupied space above and below the stones is packed with asphaltum, which in one specimen (Fig. 16) projects above the stone in a knot or button. The cement thus employed affords a fairly strong attachment, but one that apparently would not stand very rough usage. The strength of the attachments is a matter of some moment, since one of the uses which has been suggested for these implements is as clubs. To have secured a much stronger attachment it would only have been necessary to drill out the holes, so as to permit a larger surface for the handles to bear upon, which, too, would have permitted the handles to be set at right angles to the stones. In connection with their possible use as clubs, it should be mentioned that the handles are neither roughened nor knobbed for secure grasping, but, on the contrary, are perfectly smooth. The handle of the one shown in Fig. 14 is stouter than either of the others, being about an inch in diameter at its largest part, stout enough to serve as a club handle; but the handles of the other two are much smaller, being each about one-half inch thick. So slender are they, and so heavily weighted, that it is evident they would be broken at a single hard blow. So similar, however, are the three in general form and features, that, notwithstanding the difference in the size of handles, it cannot be doubted that they were designed to fulfill the same function, and that what one is all are. Ceremonial implements. After careful consideration of these implements I am convinced that their peculiarities accord best with the idea that they were the property of medicine men or conjurers, probably used in dances or superstitious ceremonies, as rain making, curing the sick, &c., this being the alternative suggested by Dr. Bowers. Not only does the character of the implements themselves agree best with this idea, but it is borne out also by the rest of the cave contents. The rudely painted notched sticks, the feather headdresses, and the bone whistles are all strongly suggestive of "medicine practices." Notched sticks similar to the ones found in the cave by Dr. Bowers are used in certain sacrifices by the Navajo, as Dr. W. Matthews informs me, and also disks of stone; the latter, however, are not perforated. Moreover, I was informed by an Indian in Santa Barbara County that feather bands or gorgets[3], of which a specimen similar to those found in the cave was shown me, were worn by all their medicine men in their ceremonies, and that the feathers of the red shafted flicker, which occur in the specimens found in the cave, were peculiarly efficacious in rain making. I was also told that bone whistles were used by the medicine men in their invocations. As already stated, therefore, a consideration of all the above facts justifies the conclusion, in my opinion, that the specimens in question, together with the rest of the contents of the cave, were the implements of trade of medicine men or the property of some religious order.

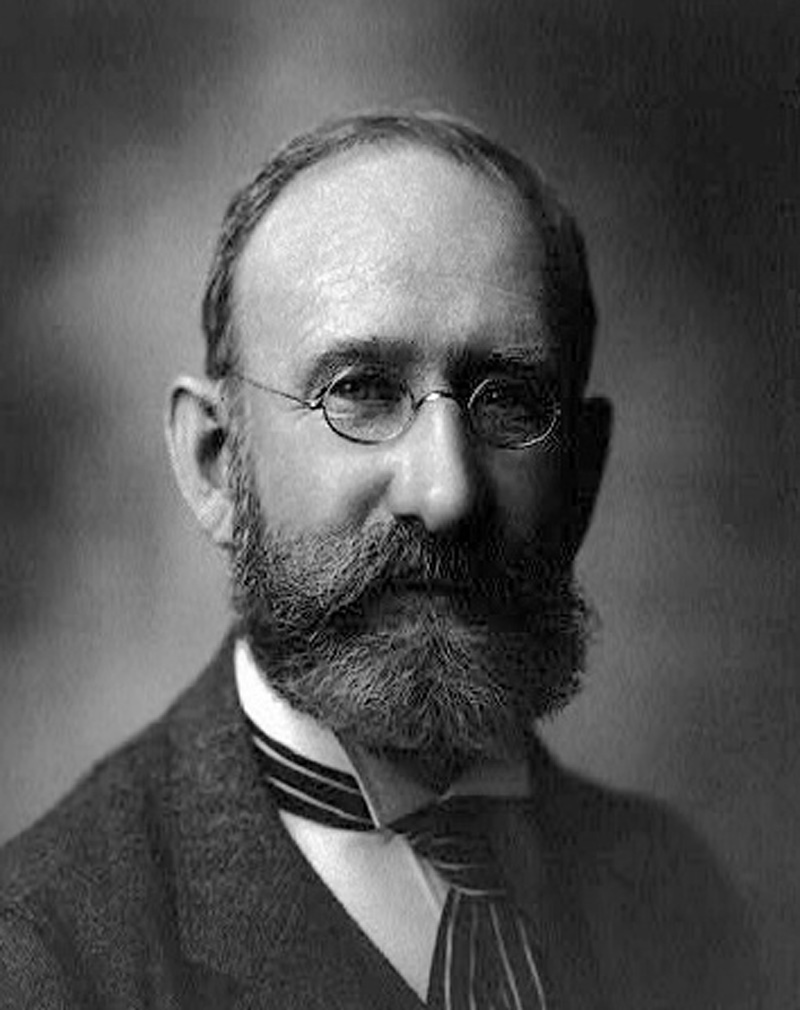

Webmasterís notes. 1. Bowers didnít discover the artifacts in a cave; he purchased them from a local rancherís son who discovered them in a cave. But Bowers wrote that he examined the cave (which he probably did), and he took credit for discovering them (which he also did, if only in a scientific context). See Van Valkenburgh 1952. 2. Frederic W. Putnam, curator of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University. 3. An ornamental collar worn about the neck, like the iridescent feathers on the throats of certain male hummingbirds.

A word about Native Californian materials in overseas museums. Blackburn and Hudson take the first comprehensive look at this topic in their 1990 work, "Time's Flotsam: Overseas Collections of California Indian Material Culture." The authors inventory tens of thousands of items — perhaps hundreds of thousands when, for instance, "misc. archaeological specimens" is listed as a single item — in 140 museums in 20 countries. To summarize: Museums trace their roots to curio cabinets kept by European royalty and aristocrats in the 16th Century. These evolved into great museums of Europe, many which were well established by the time Spain began to occupy California in 1769. Beginning in 1791 with Allesandro Malaspina (an Italian nobleman and Spanish naval officer), followed by representatives of the Russian American Co. (fur traders) along the Pacific coast, then really picking up steam under Mexican rule starting in 1822, "a respectable number of explorers, missionaries, scientists, artists and military men who visited California ... were collectors either by training or propensity" — some were better cataloguers than others — "and they returned to their homelands with a strange but often invaluable miscellany of souvenirs and specimens." The European museums filled up with booty from the land of Calafia. America was just coming into her own, and California wasn't yet part of the United States anyway. The U.S. had no major museums until the middle of the 18th Century, around the time the discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill turned American eyes westward. The Smithsonian Institution opened in 1846, Harvard's Peabody Museum in 1866, the American Museum of Natural History in 1869. They would have to play catch-up if they were to compete for prestige with their world-class European counterparts. So they sent people like Stephen Bowers to gather up as much material from California as possible — and in Bowers' case, to hurry up and do it before the French ethnographer Léon de Cessac could get it all and send it back to Paris. At one point Bowers, who did most of his collecting for the Smithsonian from 1877 to 1879 (although he generally sold to the highest bidder), decided that between Cessac and himself, they had collected so many human skulls from so many Chumash graves (they left the rest of the skeletons behind) that the museums really didn't need any more, so Bowers focused on more unique cultural items (see Benson 1997). At the time, "Chumash" was a broad identifier for peoples along the coast and for their inland neighbors including the Tataviam of the Santa Clarita Valley. Of particular interest to local readers, on a return trip Bowers purchased Tataviam cultural materials (identified as Chumash) from the discoverers of a cache cave in San Martinez Canyon near today's Val Verde community. Included were four ceremonial staffs, measuring about 18 inches, to which were attached perforated stones. Bowers had a friend at the Peabody Museum, so he sent these "Bowers Cave" items there. But that's not the end of the story. By the 1890s, the American museums were overflowing with California Indian materials — especially Chumash materials from the Channel Islands. So they began to trade them away to overseas museums for all manner of things they lacked. Among the several items the Peabody traded in 1952 to the South Australian Museum in Adelaide, Australia, was one of the four "sun staffs" found in Bowers Cave. But the Peabody was a lesser trader. By number, the biggest exporters of California's material culture were the Smithsonian; the Museum of the American Indian, founded in New York in 1916 by a wealthy collector and which by 1956 contained more than 3 million pieces; and the Denver Art Museum, whose curator from 1948-1951 was a World War II veteran who served in the South Pacific and traded many of the museum's California materials for the Oceanic objects that interested him. "As a consequence, noteworthy assemblages of California basketry that were once owned by the Denver Art Museum or formed part of (curator Eric) Douglas' own collection can now be found in museums in London, Oxford, Edinburgh, Gent, Göteborg, Stockholm and Helsinki" (Blackburn & Hudson 1990:44). "It is interesting to note that virtually all of the materials in question can be traced to only a few specific institutions: the Smithsonian Institution, the Museum of the American Indian, the Denver Art Museum, the Lowie Museum at Berkeley, the Peabody Museum at Harvard, the Field Museum (Chicago), and the Logan Museum in Beloit (Wis.)" (Blackburn & Hudson 1990:38). In sum, we see three distinct periods of removal of California Indian cultural material. First, European explorers collected ethnological materials and unearthed artifacts for several decades prior to — and several decades after — California became a part of the United States. Second, the United States, via the congressionally funded Smithsonian Institution and similar entities, exacerbated the situation in the latter half of the 19th Century and beyond by officially sanctioning "specimen"-collecting expeditions. Third, the major U.S. institutions traded away much of the collected material, scattering it to all corners of the globe.

PB39261: 19200 dpi jpeg from smaller jpeg from 4x5-inch photographic negative; Peabody photo No. 2004.24.30611 (1983). |

Bowers Cave Specimens (Mult.)

Bowers on Bowers Cave 1885

Stephen Bowers Bio

Bowers Cave: Perforated Stones (Henshaw 1887)

Bowers Cave: Van Valkenburgh 1952

• Bowers Cave Inventory (Elsasser & Heizer 1963)

Tony Newhall 1984

• Chiquita Landfill Expansion DEIR 2014: Bowers Cave Discussion

Vasquez Rock Art x8

Ethnobotany of Vasquez, Placerita (Brewer 2014)

Bowl x5

Basketry Fragment

Blum Ranch (Mult.)

Little Rock Creek

Grinding Stone, Chaguayanga

Fish Canyon Bedrock Mortars & Cupules x3

2 Steatite Bowls, Hydraulic Research 1968

Steatite Cup, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x5

Ceremonial Bar, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x4

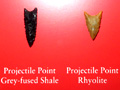

Projectile Points (4), 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig

Paradise Ranch Earth Oven

Twined Water Bottle x14

Twined Basketry Fragment

Grinding Stones, Camulos

Arrow Straightener

Pestle

Basketry x2

Coiled Basket 1875

Riverpark, aka River Village (Mult.)

Riverpark Artifact Conveyance

Tesoro (San Francisquito) Bedrock Mortar

Mojave Desert: Burham Canyon Pictographs

Leona Valley Site (Disturbed 2001)

2 Baskets

So. Cal. Basket

Biface, Haskell Canyon

2 Mortars, 2 Pestles, Bouquet Canyon

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.