|

|

Tejon Indians | Peabody Museum

Shallow basketry bowl (dimensions not listed) in the collection of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Peabody Catalog No. 64811. Attributed to Tejon Indians; no further information available. Although people lived in the Tejon area in prehistoric times, the term "Tejon Indians" generally includes people from other cultures who were brought to the San Sebastian Indian Reservation during more recent, historic times — in the 1850s (see below) — and their descendants who remained in the area into the early 20th Century, when this basket was probably made. This basket is made in the Western Mono tradition, which is characterized by horizontal bands broken by diagonal or (as in this case) vertical lines; and by using one design color (usually black, as seems to be the case here.) Note: The Peabody Museum speculates that this basket might be "Chumash?" but that's unlikely. The horizontal band is seven rows wide and starts at the third row from the rim. If it were Chumash, it would start at the seventh row. The band is interrupted by vertical elements — not a Chumash feature. The vertical elements are straight up-and-down; vertical elements on Chumash baskets usually, but not always, run diagonally. The rim is unticked; not all Chumash basket rims are ticked, but rim ticking is a Chumash characteristic. Instead, this basket has the earmarks of Western Mono basketry. Per Shanks & Shanks (2010:105), Western Mono baskets "often have the signature pattern of horizontal bands broken by vertical or diagonal designs. These baskets were usually done solely with black designs rather than the combined red and black patterns common among the Yokuts." About Tejon basketry, generally

Tejon Indian basketry and other cultural materials are often presumed to be Kitanemuk, but that is an oversimplification. It's challenging, if not downright impossible, to attribute historic (as opposed to prehistoric) Tejon materials to a specific culture when the individual maker is not known because of the removal of disenfranchised Indians from many different regions and cultures to the San Sebastian (Tejon) Indian Reservation in the mid-1800s. (See Shanks & Shanks 2010:58-61). After the mission period, which extended into the mid-1830s under Mexican rule, many mission Indians returned home only to find that their ancestral homelands had come under the control of others. In the late 1830s and 1840s the Mexican government divided those lands into ranchos and gave them away to influential Mexican citizens, leaving both mission and non-mission Indians homeless. Locally, a significant example is the Rancho San Francisco (the western SCV), which included numerous historic Indian village sites and which in 1839 was granted to the Mexican Army Lt. Antonio del Valle. A smaller example (among many) is Bouquet Canyon, which was granted in 1845 to a French sailor who became a naturalized Mexican citizen so he could own land. The U.S. government upheld most of the Mexican land patents beginning in the early 1850s and brought displaced Indians from northern Los Angeles County and Kern County to the San Sebastian reservation under the supervision of Edward F. Beale, who himself would eventually own an astounding 270,000 acres of former Indian lands. Among those removed to the reservation were persons from the Kitanemuk (Antelope Valley), Tataviam (Santa Clarita Valley), Yokuts, Kawaiisu, Serrano and Chumash cultures, and possibly others. Some of these so-called "Tejon" Indians appear in both the Cooke-Garcia line and the Fustero line of native Santa Clarita Valley (Tataviam) residents. (See Generation 4 in the Fustero timeline and Generation 7 in the Cooke-Garcia timeline.) One example in the Fustero line is Estanislao (Cabuti), aka Stanislaus, a Tataviam speaker born about 1796 at Tochonanga (modern Newhall). He was brought to the San Sebastian reservation where he inherited his father's title of chief. On the other hand, some were indigenous Tejon Indians. A woman known as Crisanta was born about 1797 at the Tejon-area village of Tectuaguaguiyajavia and remained there until 1821 when she went to the Mission San Fernando. Crisanta and her villagers spoke Kitanemuk, and her grandfather's village in the Antelope Valley was Serrano-Kitanemuk. Crisanta was the mother of Sinforosa Fustero (b. 1834), the mother of Juan Jose Fustero (b. 1850). Crisanta was probably responsible for the fact that Sinforosa spoke Kitanemuk; Sinforosa's father (Crisanta's husband), Narciso (b. ~1798), hailed from Piribit village, aka Pi-irukung, in the lower Piru Creek drainage area, now under Lake Piru, and spoke Tataviam. (Sinforosa's husband Jose Fustero spoke Kitanemuk despite having Tataviam parents and being born in the SCV. He may have learned it at the mission as a child, having been baptized there at age 5. Their son Juan Jose was three-quarters Tataviam by birth but he didn't speak the language; he spoke Kitanemuk and Spanish.) See Johnson and Earle 1990. Even after the short-lived San Sebastian reservation was officially disbanded during the American Civil War, many Indians who had come from other places remained there and raised their families there. Women at Tejon continued to make baskets into the 20th Century, often for sale to tourists, and those baskets reflected the maker's individual cultural traditions. The upshot is, we don't always know the culture of the individual who made a basket in modern (historic) times at Tejon. It could be Kitanemuk or Tataviam, but not necessarily. We don't know what Tataviam decoration looked like. There is only one decorated basket that is known with certainty to be Tataviam; it's the circa-1800 mortar hopper found in Bowers Cave. Sinforosa had baskets, but it's unclear whether she made them. If she did, they probably reflected the traditions of her Kitanemuk mother from Tejon — who in turn might have been influenced by others. "When California Indian people migrated they typically retained smoe of their own basketry traditions and adopted others from new people they encountered" (Shanks et al. 2010:103). Sinforosa would likely have been taught the art by her mother; basketry was almost always taught by and made by women.

PB64811: 19200 dpi jpeg from smaller jpeg from 2.25-inch photographic negative; Peabody photo No. 2004.24.41434 (1985). |

Bowers Cave Specimens (Mult.)

Bowers on Bowers Cave 1885

Stephen Bowers Bio

Bowers Cave: Perforated Stones (Henshaw 1887)

Bowers Cave: Van Valkenburgh 1952

• Bowers Cave Inventory (Elsasser & Heizer 1963)

Tony Newhall 1984

• Chiquita Landfill Expansion DEIR 2014: Bowers Cave Discussion

Vasquez Rock Art x8

Ethnobotany of Vasquez, Placerita (Brewer 2014)

Bowl x5

Basketry Fragment

Blum Ranch (Mult.)

Little Rock Creek

Grinding Stone, Chaguayanga

Fish Canyon Bedrock Mortars & Cupules x3

2 Steatite Bowls, Hydraulic Research 1968

Steatite Cup, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x5

Ceremonial Bar, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x4

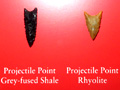

Projectile Points (4), 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig

Paradise Ranch Earth Oven

Twined Water Bottle x14

Twined Basketry Fragment

Grinding Stones, Camulos

Arrow Straightener

Pestle

Basketry x2

Coiled Basket 1875

Riverpark, aka River Village (Mult.)

Riverpark Artifact Conveyance

Tesoro (San Francisquito) Bedrock Mortar

Mojave Desert: Burham Canyon Pictographs

Leona Valley Site (Disturbed 2001)

2 Baskets

So. Cal. Basket

Biface, Haskell Canyon

2 Mortars, 2 Pestles, Bouquet Canyon

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.