Chuck Daughtrey: A Renaissance Man of Numismatics

By Leon Worden

March 2006

|

| "N |

No, he hasn't discovered an innovative technique for designing coins. He isn't even a sculptor.

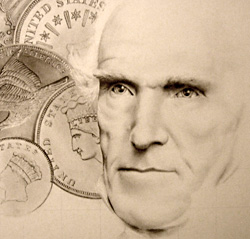

Rather, this 37-year-old ex-military computer technician from Springfield, Missouri, has combined his love of numismatics with his raw artistic talent to create something brand new: framable, limited-edition pencil drawings of famous coin artists.

And they are good.

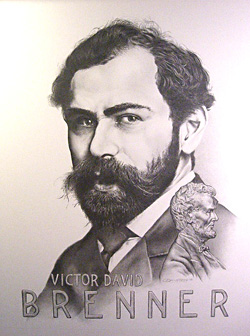

The deep, pensive eyes of Victor D. Brenner lure you in. Daughtrey's rendition of the Lincoln cent designer was the first in a series of 12 to 18 subjects he intends to complete by summer. Augustus Saint-Gaudens, designer of early 20th-century $10 and $20 gold coins, was No. 2; Indian Head cent creator James B. Longacre is under way.

"I decided to do the Brenner piece because I didn't have a good picture of the guy who designed the coins that I collect, and I wanted a good picture of him," said Daughtrey, who specializes in Lincoln cent varieties. He makes his livelihood identifying them, attributing them, buying and selling them, writing books about them and publishing online reference materials about them.

While Daughtrey's bust of Brenner fills most of the 11x14-inch canvas — actually, Strathmore 300 Bristol paper — Brenner's visage is juxtaposed against a small bust of Lincoln, making it instantly identifiable to millions of people who collectively have seen billions of Lincoln cents through the years.

"I dare say Brenner's work is one of the most duplicated works of art in history," Daughtrey said, "but his likeness is nothing more than an afterthought in most arenas."

No more. Friends encouraged Daughtrey to do prints. He made 250 in early November and sold a third of them within weeks. Inside of a month, he'd gotten some high-octane attention.

"I was first struck by the photorealism of Charles' portrait of Victor David Brenner. Then I saw his rendition of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, any my initial impression was confirmed: We numismatists have a rare talent in our midst," said Publisher Dennis Tucker of Whitman Publishing LLC, a market leader in coin albums and manuals including the annual "Guide Book of United States Coins."

Look for Daughtrey's work in a Whitman book this year when Tucker publishes "A Guide Book of Flying Eagle and Indian Head Cents" by early small-cent specialist Rick Snow.

"I thought, what better way to share Charles' work with the hobby community than to include a James Longacre portrait in this new book?" Tucker said. "I think collectors will enjoy seeing their favorite coin designers in this new, very creative light."

Daughtrey connected with Tucker and author Q. David Bowers at the Baltimore Coin and Currency Convention in early December.

"Dave [Bowers] happens to be finishing up 'A Guide Book of Washington and State Quarters' for Whitman," Tucker said, "so he talked to [Daughtrey] and set up a [John] Flanagan portrait, as well."

"I liked what I saw," said Bowers. "Charles Daughtrey's images are exceedingly well done and add to the artistic assets of the numismatic hobby."

There's no telling where Daughtrey might be, had he studied art in college and tried to make a living at it before now. But he didn't. Not only was the Brenner piece in November 2005 his first coin artist portrait; it was also his first professional art of any kind.

"If I'd just come out of art school, I never would have thought of this," Daughtrey said. "It was because I've been going through 'coin school' for all these years that I thought about doing the art."

|

Along the way he developed an interest in Lincoln cents. As a youngster he was popping "pennies" into blue Whitman albums — what goes around is coming around — and in high school he picked up a copy of "The Lincoln Cent Doubled Die" by John A. Wexler, a pioneer in Lincoln cent varieties.

"I just thought that was really interesting," Daughtrey said, "so I started looking for them, and I found one." It was a 1972 Die No. 2. "That started the whole thing."

But the "art thing" was shelved when Dad gave him "the talk."

"[He] said you're never going to make it anywhere in art. Nobody does. You need to do computers."

So he did computers. He joined the Air Force out of high school and spent the next 10 years as a mainframe computer and data transfer operator. He was a "ground pounder" for AWACS during the first Gulf War; his unit won the Bronze Star during an attack on Riyadh "because of our organization in assembling three different branches of service together," he said.

"It was a pretty horrific time for me," he said. "Of course, I can't imagine that a war would be the best time in anybody's life."

His military career was discouraging on a personal level, as well. "I tried for the last five years that I was in [the Air Force] to be transferred over to the graphics shop" so he could flex his artistic muscle. But "I was continually buttoned down and told no, because I was needed more in my job than they needed me in that job."

He left the service in 1996. A month later, he and his wife, Evie, had a son, Michael. He moved his family back to Springfield, and he's been getting as far away as he can from mainframe computers ever since.

He still designs the occasional Web site and teaches programming at Missouri State University, but as with his art, eventually he would meld his high-tech talents with numismatics.

"Every die is unique, just like snowflakes," he said. "Each die has a fingerprint, part of it being the doubling [if any], the rest of it being markers such as scratches and die flow lines that you can use to identify two coins as having been struck by the same die."

With a 10-power Belomo loupe or an infinite zoom stereo microscope set at 12-power (20- to 35-power for photographing), Daughtrey has found "probably between 500 and 800 [varieties] that I didn't know existed."

Daughtrey said it's the investigative aspect of the work that drew him to this intensely focused specialty.

"What I've always enjoyed most about it was that I could find two different coins from two different hordes from two different states that were collected during two different time periods, and marry two coins together that came from the same die that were produced on the same day."

"Some people enjoy toning," he said. "Some people enjoy the rarity of their coins. Well, I enjoy the doubling."

He's not alone. There are enough variety collectors, particularly among Lincoln cents and Morgan dollars, to sustain several different "attribution services," each with its own die numbering system. Daughtrey receives 1,000 to 2,000 e-mail inquiries per week; he has his own numbering system.

"ANACS is encapsulating to my system," Daughtrey said. "That's one of the breakthrough things in this industry, when a [coin grading] company recognizes your system and will slab to that system. You're suddenly more recognized, professionally recognized."

ANACS also encapsulates Lincoln cents to other numbering systems, such as Fivaz-Stanton varieties (from "The Cherrypicker's Guide to Rare Die Varieties" by Bill Fivaz and J.T. Stanton). Some coin grading services recognize Lincoln die systems developed by CONECA (Combined Organization of Numismatic Error Collectors of America) and by Daughtrey's early inspirer, Wexler, who is currently affiliated with the National Collectors Association of Die Doubling.

|

For the "want it now" crowd, Daughtrey self-published his first edition of "Looking Through Lincoln Cents: Chronology of a Series," in 2004. At 304 pages and rife with Daughtrey's own coin photography, it's complete enough to satisfy most Lincoln cent enthusiasts. In 2005, numismatic book publisher Zyrus Press picked it up and put out a second edition at 350 pages.

What might easily have developed into a competition with veteran Lincoln cent expert Sol Taylor, author of "The Standard Guide to the Lincoln Cent," actually became a collaboration when the two men hooked up in July at the American Numismatic Association's "World's Fair of Money" in San Francisco.

"[Daughtrey] is a very talented guy," said Taylor, who recruited Daughtrey to edit the Lincoln Cent Quarterly, the publication of the Society of Lincoln Cent Collectors, which Taylor heads.

First, a drawing in pencil of the famous $5 "Educational Series" silver certificate of 1896, where "the note itself is in perspective, like it's sitting on a table, and the vignette is popping up out of the note, coming to life."

Then, "possibly some original color work" to hang in the homes of high-end coin collectors, he said. "Just imagine a 22x22-inch frame on the wall that's got a huge oil painting of your favorite coin in it."

Acrylic and oil are more challenging for him than pencil and charcoal because he is seriously colorblind.

"I don't see very many colors at all," he said. "I have to have my son or my wife help me. I'll paint something and they'll tell me, 'That's the wrong color,' and I'll change it."

"I can see what I need to do. The paint tubes have names on them, and I can see shapes. I can see the lights and darks, and I can see tonal changes," he said. "I've done color work before."

What the heck. Beethoven was deaf.

Writing, publishing, examining coins and now drawing, this up-and-coming Renaissance man of numismatics still sees himself as "one of the little guys trying to pound out a living."

"My wife is really proud that I'm actually doing artwork again," he said. "I dropped it for so many years because I didn't see where it would make money,"

"I barely make enough to pay the bills," he said. "Honestly I don't charge enough for what I do, and I need to overcome that."

©2006 MILLER MAGAZINES INC./LEON WORDEN. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.