The Battle Over 'In God We Trust'

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

March 2006 / April 2006

Published in two parts

| I |

Michael Newdow doesn't, and he's making a federal case of it.

Newdow is the California atheist who achieved national notoriety when he sued to remove the words, "under God," from the pledge of allegiance. In November he filed a new lawsuit, and this time he's aiming to remove the words, "In God We Trust," from the nation's coins and paper money.

The federal government and at least two public-interest law groups are girding for battle.

"The whole thing is about equality," said Newdow, who believes the motto on currency "reinforc[es] the twin notions that belief in God is good and disbelief in God is bad," thus relegating him to the status of a second-class citizen.

Newdow lodged his complaint Nov. 18, 2005, in federal court in Sacramento. He's suing the United States of America and Congress, as well as Treasury Secretary John Snow and Peter Lefevere, who oversees the publication of federal laws.

Also named are Henrietta Holsman Fore, former director of the U.S. Mint, which has produced coins bearing the motto, "In God We Trust," since 1864; and Thomas A. Ferguson, director of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, which has produced paper money with the motto since 1957. (Newdow didn't know Fore had left the Mint in August; that fact does not invalidate the complaint.)

A coin collector since age 7 or 8, Newdow, now 52, told the court he is "virtually always confronted with the words, 'In God We Trust,' when I look at the coins and currency [sic]. I would estimate that this occurs on average at least five times a day."

Newdow told COINage that as a kid, he would take $10 to the bank and exchange it for coins "when there was still silver in them" prior to 1965. He doesn't buy a lot today other than mint and proof sets.

"I once had a 1942-over-1 dime," he remembered. "I got it in the cafeteria line in the seventh grade. It was in perfect shape but it had some yellowish stuff on it. Like a jerk, I cleaned it. I've been kicking myself ever since."

Today the coin would be worth about $7,000 in almost-uncirculated condition (AU-50), somewhat less with "yellowish stuff on it," and far less if poorly cleaned. He still has the coin.

Newdow is challenging the words that confront him five times a day on constitutional and statutory grounds.

"'In God We Trust' implies there is a God, which is disputed by millions of American citizens," he told the court. "It violates the religious neutrality required by the establishment clause" of the First Amendment, which reads, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion."

While the clause is commonly interpreted to mean government shall not favor one religious sect over another, Newdow sees it more broadly. "The simultaneous endorsement of all monotheistic religions is no less constitutionally infirm than the endorsement of any one of those monotheistic religions alone," he asserts.

He says the motto also violates his "free exercise" rights in the First Amendment. He cites the Mint's 2003 annual report, which notes, "Whenever United States coins travel, they serve as reminders of the values that all Americans share. ... Our coins are small declarations of our beliefs."

"I have traveled to numerous foreign lands," Newdow told the court, listing 44 countries. "I frequently would need to exchange small quantities of American currency in order to avoid financial losses due to exchanges of large-denomination [travelers'] cheques." As such, the government has "required me to evangelize for a religious view I explicitly deny."

The motto survived a full century on the nation's coins without a court challenge, but Newdow is not the first go down this road. Three federal appellate panels in three different judicial circuits rejected all three previous lawsuits.

In 1970, the 9th Circuit Court in California ruled in Aronow v. United States that the motto "has no theological or ritualistic impact." In 1979, dismissing a complaint from the outspoken atheist Madelyn Murray O'Hair, the 5th Circuit Court in Texas said the motto "is of a patriotic or ceremonial character and bears no true resemblance to a governmental sponsorship of a religious exercise."

In 1996, the 10th Circuit Court in Colorado held that the motto's "primary effect is not to advance religion; instead, it is a form of 'ceremonial deism' which through historical usage and ubiquity cannot be reasonably understood to convey government approval of religious belief."

Even the state of Ohio's motto, "With God, All Things are Possible" (Mathew 19:26), passed constitutional muster in the 6th Circuit in 2001.

Newdow thinks he has a better shot than O'Hair and other challengers because of the strength of his arguments. He devotes several pages to his claim that the Constitution is a "completely secular document" and that the framers purposefully kept religion out of it — "in striking contrast to the Declaration of Independence" — in which Thomas Jefferson, a non-Christian deist, held that all men "are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights."

"There's a wealth of information" in the complaint, Newdow told COINage. "The others didn't have anything like that."

The Pacific Justice Institute thinks much of that information is "vague and ambiguous." The California nonprofit group is seeking to intervene as a defendant.

"We represent the interests of organizations and persons of faith," PJI attorney Kevin T. Snider told COINage. "Citizens with religious beliefs have an interest in the outcome of the litigation and thus should have a voice in the court."

Another group that's rushing to the defense is the Washington, D.C.-based American Center for Law and Justice, which has fought Newdow in the past. "This lawsuit is another attempt to use the legal system to remove a legitimate reference to the religious heritage of America," ACLJ attorney Jay Sekulow said in a statement.

In its policy papers, ACLJ notes that the Supreme Court has ruled that "this is a religious nation" (Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States, 1892), and that "We are a religious people whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being" (Zorach v. Clauson, 1952).

The more joiners the merrier, Newdow says. He thinks intervening religious organizations bolster his idea that "In God We Trust" serves a religious, and not a secular, purpose. The government itself has until mid-February to respond to the complaint.

|

The frieze is the work of Adolph A. Weinman, designer of the "Mercury" dime and the Walking Liberty half dollar. Both coins affirm the nation's trust in God.

DOCTOR, LAWYER, CLERGYMAN

Born in the Bronx and raised in the New Jersey suburbs, Newdow lived in North Carolina and Florida before moving to California. A board-certified locum tenens ("fill-in" or "substitute") physician, he studied law so he could advocate for health-care reform. He graduated from the University of Michigan Law School in 1988 but didn't take his first bar exam until 2002 in California. He passed.

By that time he was already advocating to remove the words, "under God," from the pledge of allegiance that his daughter, Glen, was reciting daily at school in Elk Grove, outside Sacramento. The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals sided with Newdow in 2002, but the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed the complaint in 2004 on grounds that Newdow did not have custody of Glen and thus couldn't speak for her. (According to press reports, the girl's mother, Sandra Banning, a Christian Sunday-school teacher, said her daughter enjoyed reciting the pledge, God and all.)

Newdow found new plaintiffs and refiled. On Sept. 14, 2005, U.S. District Judge Lawrence Karlton agreed with Newdow that "under God" violated the plaintiff school children's constitutional right to be "free from a coercive requirement to affirm God." The case is on appeal and probably won't come up again until 2007.

When Newdow first lodged his "under God" complaint in 1998 it was actually an "In God We Trust" challenge. In fact, it was his "inspection of the coins and currency [sic] in my hand" over Thanksgiving 1997 that he "again noticed" the motto, which he "had always considered offensive." It was then that he "initiated my efforts to end the religious inequality that has been unconstitutionally spatchcocked into our government."

While the nation's currency is what set him on his litigious path, he changed the focus of his first lawsuit to the pledge of allegiance because, he told COINage, "I realized that 'under God' was a stronger case."

"That was before I knew about RiFRA," he said.

RiFRA is the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, passed by Congress in 1993 to prohibit the government from "substantially burden[ing] a person's exercise of religion" without "a compelling governmental interest."

Newdow told COINage he believes it's his best argument. "I think that's how I'll win. I think I'll get [the motto] off [money] because I can't practice my religion."

That's right. His religion.

Newdow was ordained as a minister in 1977 in the Universal Life Church, whose policy is to "ordain anyone who asks, without question of faith." Newdow joined at a time when Universal Life's status as a "real" church was being challenged in court. It prevailed.

In 1998, Newdow formed his own atheist church, the First Amendmist Church of True Science, or FACTS.

Newdow identifies himself as a Grand Lubitz — one who adheres to the three "suggestions" that form the basis of the religion. ("We are not so arrogant as to have 'Commandments,'" he told the court.) The suggestions are: "(1) Question; (2) Be Honest, and (3) Do What's Right" — similar to Universal Life's credo, "Doing that which is Right."

Newdow told the court it would be "a violation of Suggestions (2) and (3) for FACTS members to accept money that has the words, 'In God We Trust,' while seeking to raise funds for our church, which specifically denies that claim."

Just how many FACTS members there are is "a complete unknown," he told COINage.

He told the court that in October, he tried to hold a FACTS fund-raiser but couldn't accept cash "because my religious tenets forbid me from accepting that money." He put further fund-raising activities on hold.

"Simply being forced to carry the religious message [on money] infringes upon Newdow's free exercise rights," his complaint states. "Could the government make a Jew carry coins with crucifixes as the price to pay for carrying cash? A Hindu carry currency depicting Buddha? A Catholic carry money with clearly marked King James versions of the Bible? Why is government in this business altogether?"

U.S. COINAGE BEFORE 'GOD'

For the first seven decades, the nation's federal coinage made no mention of God. In fact, the earliest coins depicted something quite different.

"Upon one side of each of the [authorized] coins there shall be an impression emblematic of liberty, with an inscription of the word Liberty," Congress directed in the Coinage Acts of 1792 and 1837.

Although it carried no religious overtones at the time, the particular device that was selected to be "emblematic of liberty" was the pre-Christian Roman goddess Libertas, the Goddess of Liberty.

Her appearance on the nation's coinage is directly traced to Benjamin Franklin, a man who shunned his Puritan upbringings and embraced European enlightenment during the Age of Reason.

Lacking coinage facilities of its own, the Continental Congress, beginning in 1776, commissioned 11 medals from the Paris Mint to commemorate major victories in the Revolutionary War. As Minister to France from 1776 to 1785, Franklin got to know the world's finest medallic artists. He personally commissioned a 12th medal to celebrate America's dual victories over Gen. "Gentleman Johnny" Burgoyne at Saratoga in 1777 and Gen. Charles Cornwallis at Yorktown in 1781.

[click to enlarge]

Sculpted by Augustin DuprÈ in 1782, the obverse ("heads side") of Franklin's medal shows a female bust with flowing hair and a Phrygian cap surrounded by the words, "LIBERTAS. AMERICANA." On the reverse, to curry favor with France, Franklin shows France as the Roman goddess Minerva; America as the infant Roman god Hercules; and the British as a cowardly lion with its tail between its legs. Above them are words suggested to Franklin the by prominent English barrister and linguist Sir William Jones: "NON SINE DIIS ANIMOSUS INFANS." The line is from Horace (65 B.C. to 8 B.C.): "The courageous child was aided by the gods."

The medal was an instant hit. About two dozen were made in silver and many more in copper, which Franklin actually preferred. They passed to European diplomats. Thomas Jefferson gave one to George Washington. One went to the president of the Continental Congress, Elias Boudinot, who became the third Mint director in 1795.

Libertas Americana was the face of the new nation.

Walking, standing, or merely facing left or right, she would grace America's coins for more than a century.

The Libertas medal wasn't Franklin's only foray into coin design. He is credited with the decidedly secular mottoes such as "Mind Your Business" and "We Are One" that appear on the first coins minted on the authority of the United States, the Fugio cents of 1787 — often called "Franklin cents." He was probably responsible for similar mottoes on the Continental Currency coinage of 1776.

At the time, it was common to use "classical" pagan allegorical figures to depict concepts such as liberty and justice. For instance, the blindfolded woman carrying the scales "is a Greek mythological character whose name in Latin is Themis," according to the U.S. Justice Department, which says she is "daughter of Uranus, i.e., Heaven, and Gaea, i.e., Earth, and thus one of the Titans," as well as "the wife, before Hera, of Zeus." George Washington called her "the firmest pillar of government."

This tradition continued for many years. Statues of Mars, the Roman god of war, and Pax, goddess of peace, flank the entry to the U.S. Capitol, whose dome is topped by the Italian-made Statue of Freedom, aka Libertas.

And then there's the great, big statue of Libertas, as French sculptor FrÈdÈric-Auguste Bartholdi called her, in New York Harbor.

Michael Newdow isn't bothered by the winged goddess Libertas (often mistaken for Mercury, the Roman god of trade and commerce) on his 1942/1 dime.

"I don't think Americans identify it as a goddess," he said. "I think they see it as [the concept of] liberty. ... It's not there for religious reasons."

But the presence of Libertas on the nation's coins — and the exclusion of the Almighty God therefrom — bothered the heck out of Mark R. Watkinson.

TO GOD WE ENTRUST OUR COINS

Pastor of the First Particular Baptist Church in Ridleyville, Penn., Watkinson was worried.

[click to enlarge]

Battle lines were drawn. It had been eight months since the first shots were fired on Fort Sumter. Young men were dying by the thousands. The nation was tearing itself asunder and no end was in sight.

"One fact touching our currency has hitherto been seriously overlooked," Watkinson wrote to Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase on Nov. 13, 1861. "I mean the recognition of the Almighty God in some form on our coins."

"You are probably a Christian," he told Chase. "What if our Republic were now shattered beyond reconstruction? Would not the antiquaries of succeeding centuries rightly reason from our past that we were a heathen nation?"

(There are several variations of Watkinson's letter floating around. This reference chiefly follows the Treasury Department's version.)

Watkinson proposed that "instead of the Goddess of Liberty," the nation's coins should depict 13 stars, the American flag, the all-seeing eye crowned with a halo, and the words, "God, Liberty, Law."

"This would make a beautiful coin, to which no possible citizen could object. This would relieve us from the ignominy of heathenism. This would place us openly under the Divine protection we have personally claimed. From my hearth I have felt our national shame in disowning God as not the least of our present national disasters."

Seven days later, Chase — a former senator who would later serve as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court — wrote to his subordinate, Mint Director James Pollock:

"No nation can be strong except in the strength of God, or safe except in His defense. The trust of our people in God should be declared on our national coins. You will cause a device to be prepared without unnecessary delay, with a motto expressing in the fewest and tersest words possible this national recognition."

Pollock, former governor of Pennsylvania, set to work experimenting with half dollars and gold coins. Chief Engraver James Barton Longacre, whose diaries indicate he was deeply religious, prepared several patterns with the motto, "God Our Trust."

Pollock explained in a Dec. 26, 1861, letter to Chase: "The motto adopted ['God Our Trust'] was selected in consideration of its having become familiar to the public mind by its use in our great National Hymn, the 'Star Spangled Banner.'"

The hymn's fourth stanza includes the phrase, "Then conquer we must, for our cause it is just, and this be our motto: 'In God is our trust.'"

Chase evidently dragged his feet, because Pollock reminded him six months later that he hadn't replied. It was late 1863 before Chase got on the ball.

By that time, 11 Protestant denominations had teamed up to form the National Reform Association. Its aim was to reform the Constitution to "indicate that this is a Christian nation." Pollock was a member.

The association wanted to change the Constitution's preamble to read: "We, the people of the United States, humbly acknowledging Almighty God as the source of all authority and power in civil government, the Lord Jesus Christ as the Ruler among the nations, His revealed will as the supreme law of the land, in order to constitute a Christian government, and in order to form a more perfect union..."

[click to enlarge]

Spiritual concerns soon collided with economic ones. The United States was exporting gold to pay for the foreign nickel it was importing and using in the 88-percent copper, 12-percent nickel Flying Eagle cents of 1857-1858 and the first Indian head cents of 1859-1864.

Climbing foreign nickel prices prompted Pollock to recommend the replacement of copper-nickel with a new-fangled alloy then in use in France and England, called "bronze." This 95-percent copper, 3-percent tin and 2-percent zinc composition "makes a beautiful and ductile alloy," Pollock wrote to Chase on Dec. 8, 1863.

In the same letter he recommended production of a new denomination, a two-cent piece, at precisely twice the weight of the cent.

The new denomination's devices "are beautiful and appropriate," Pollock wrote, "and the motto on each such, as all who fear God and love their country, will approve."

Chase amended "God Our Trust" to read, "In God We Trust," and Pollock drafted what became the Mint Act of April 22, 1864. Congress authorized the two-cent coin and left the inscriptions to the discretion of Chase and Pollock.

The Mint produced 19.8 million two-cent coins in 1864. They were the first circulating U.S. coins to bear the words, "In God We Trust."

Not until the following year, March 3, 1865, did Congress directly authorize the motto in so many words: "In addition to the devices and legends upon the gold, silver and other coins of the United States, it shall be lawful for the director of the Mint, with the approval of the Secretary of the Treasury, to cause the motto 'In God we trust' to be placed upon such coins hereafter to be issued as shall admit of such legend thereon."

The motto was added to the Seated Liberty (Libertas!) quarter and the Shield nickel in 1866, and to higher-denomination silver and gold coins over the next 40 years.

Then came Teddy Roosevelt.

When old TR commissioned the Irish-born Augustus Saint-Gaudens to sculpt new $10 and $20 gold coins in 1905 (minted in 1907), they omitted "In God We Trust." To Saint-Gaudens, the motto was an "inartistic intrusion" that was allowed but not required under the prevailing Coinage Act of 1873.

To the God-fearing Roosevelt, putting the motto on something so base as the nation's instruments of commerce "is in effect irreverence, which comes dangerously close to sacrilege," he said.

Plus, the particular phrase, "In God We Trust," struck a dissonant chord with the Republican president. He favored keeping a national gold standard, while Democrats and Nevada silver miners wanted to put the nation on a formal gold-and-silver standard at a ratio of 16:1. Mining lobbyists erected large roadside signs showing a silver dollar with the slogan, "There is only 63 cents worth of silver in this dollar. ... In God We Trust for the balance." Some merchants displayed signs reading, "In God We Trust. All Others Cash."

Roosevelt's motivations were misunderstood. The public was outraged. Congress responded with an act declaring that "In God We Trust" must appear on whichever denominations of gold and silver coins had borne the words in the past. Roosevelt signed the law May 18, 1908, and all subsequent Saint-Gaudens coinage bore the motto.

Where the motto showed up next was on the basest of all coins.

Roosevelt liked the work of the Lithuanian-born sculptor Victor David Brenner and asked him to adapt his popular medal of Abraham Lincoln as a coin to honor the Great Emancipator's 100th birthday.

It might seem apropos for the Lincoln cent to bear the words "In God We Trust." After all, they first entered the numismatic nomenclature while Lincoln was president; and Lincoln coined the phrase, "under God," which would later be grafted onto to the pledge of allegiance. But placing the motto on the Lincoln cent was neither Roosevelt's nor Brenner's idea.

Rather, it was TR's Republican successor, William H. Taft, who demanded the motto on the cent, after Brenner's designs were thought to be completed and before they were approved.

Except for the Buffalo nickel, all subsequent coin designs incorporated the motto.

|

At this point, U.S. paper money was still silent about God, except for the reverse of the Great Seal of the United States, which appeared on the $1 bill.

Adopted in 1782, the seal was the work of several founders, including Jefferson, Franklin and John Adams. It shows an unfinished, 13-stepped pyramid crowned with an all-seeing eye, which in Jefferson's deist vernacular reflected the Grand Architect of the Universe. Above it are the words, "Annuit Coeptis," adapted from the plea in Virgil's Aeneid: "Jupiter, favor my undertakings." The tense was changed to the affirmative, "favors," so that the Great Seal asserts, "Providence favors our undertakings." The current U.S. State Department translation is, "He (God) has favored our undertakings" (parenthetic included).

That wasn't good enough for Matthew H. Rothert.

Here it was, 1953. Joe McCarthy was getting the job done on the Senate floor, but couldn't the United States do more to broadcast to the world the supremacy of its ideals over those of the godless Soviets?

Rothert, president of the Arkansas Numismatic Society (and later president of the American Numismatic Association from 1965-67), was in church one November day in his hometown of Camden when he noticed that the coins in the collection plate proclaimed the nation's trust in God, but the paper money didn't.

In a speech to the Arkansas numismatists on Nov. 11, 1953, he suggested that since U.S. paper money circulates widely abroad, it could spread a message about the nation's faith in God.

Rothert lobbied high government officials. Florida Democrat Charles E. "Charlie" Bennett introduced a bill in the House and then-Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson introduced a companion bill mandating that "the inscription 'In God We Trust' ... shall appear on all United States currency and coins [sic]" as soon as the Bureau of Engraving and Printing adopted new dies.

President Dwight Eisenhower signed the bill on July 11, 1955. The BEP was in the process of switching from 18-note plates to 36-note plates, and from "wet" presses (which moistened the paper as it was printed) to high-speed, dry intaglio presses. The new presses were first used and the motto was first added to $1 silver certificates in October 1957. By 1966 all denominations were converted and bore the motto.

Technically, this wasn't the first time "In God We Trust" appeared on national paper money. In 1863 and again in 1875 and 1882, national bank notes bore the seal of the state in which they were issued. Florida's motto happened to be "In God We Trust." Also, $5 silver certificates of 1886 depict five silver dollars. Portions of the motto are discernable on four of them. And according to numismatic researcher Robert W. Julian and paper money specialist Gene Hessler, "In God is our Trust" and "God and our Right" appeared late in the Civil War on certain Compound Interest Treasury notes and Interest Bearing notes that were authorized under an act of March 3, 1863.

Ironically, in all this time, "In God We Trust" was not the official motto of the United States.

A year after his currency act, Bennett introduced a bill stating simply, "'In God We Trust' is the national motto." Eisenhower signed the bill into law July 30, 1956.

In approving the new motto, the House Judiciary Committee reported that it "recognizes that the phrase 'E pluribus unum' has also received wide usage in the United States. However, the committee considers 'In God We Trust' a superior and more acceptable motto." Besides, it has an "inspirational quality in plain, popularly accepted English."

Somebody really ought to tell the U.S. General Services Administration. Today, in its online description of the Great Seal of the United States, the GSA says the seal includes "the motto of the United States, E pluribus unum, meaning out of many, one."

OUT OF MANY, NONE

Michael Newdow sees no "historic" reason to keep "In God We Trust" as the nation's motto. Ben Franklin's "E pluribus unum" was the "de facto motto of the United States [for] 180 years from 1776 to 1956," he told the court.

[click to enlarge]

He also sees no difference between the "ceremonial deism" embodied in the words, "In God We Trust," and the "ceremonial racism" that would be reflected in the words, "In White Superiority We Trust," or the historic chauvinism of "In Male Dominion We Trust."

"There are all sorts of historical violations of the equality that underlies our constitutional framework," he asserts. "'In God We Trust' is ... not excusable because of any 'historical' significance. [It] was intended to be clearly and unequivocally religious."

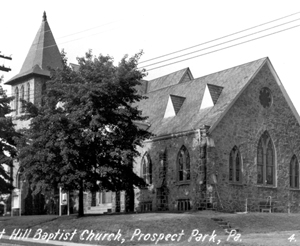

To Pastor Robert Zimmerman of Prospect Hill Baptist Church, the notion that "In God We Trust" inhibits Newdow's own religious freedom "is just more lunacy, as far as I'm concerned."

The name has changed, but Prospect Hill Baptist is the same church in Pennsylvania where Mark Watkinson set this ship a-sail in 1861.

"I just think [Newdow's claims are] culturally in keeping with the radical left agenda in our society, which has no respect for the majority [of Americans] or for history," Zimmerman said. Those who litigate over the word "God" are "out of step, not only with our founding fathers, but with the majority of the people who live in this society."

While Zimmerman doesn't agree with his ecclesiastical predecessor's notion that merely recognizing the Almighty God on coins would somehow elicit additional "divine protection," he does think it's a good idea to keep Him there.

"We can [either] view material goods as ... capitalistic gifts, or we can view [them] as a privilege, something to be viewed more humbly," he said. "I think when someone becomes aware of 'In God We Trust' placed upon the coinage, [it] may make us more conscientious about where our abundance comes from. And that coin that buys something ... can be symbolic of a recognition of God as the Giver of all good gifts."

Jefferson and other deist founders "might not have been Christians," Zimmerman said, "but they believed in a Creator, and they claimed to believe in God Almighty. And that's good enough for me."

©2006 MILLER MAGAZINES INC./LEON WORDEN. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.