A Hobby in Transformation

By Leon Worden

| T |

Was the coin exchanged for a meal or shelter? Was it used to bribe a railroad bull into looking the other way?

To Del Romines, hobo nickels are things of the past. They are little pieces of history to be collected and revered, a brand of folk art that vanished in the 1950s.

"There were just very few that were actually made after that," Romines told COINage in March.

A retired metal fabricator in Louisville, Kentucky, Romines considers later carvings "fakes" at worst, and at best something other than "honest-to-goodness hobo nickels." The sole exceptions for Romines are the works of George Washington "Bo" Hughes, a black hobo who started carving Buffalo nickels when they came out in 1913 and kept carving them until late 1981 or early 1982 when he disappeared from a hobo jungle in Florida, never to be seen again.

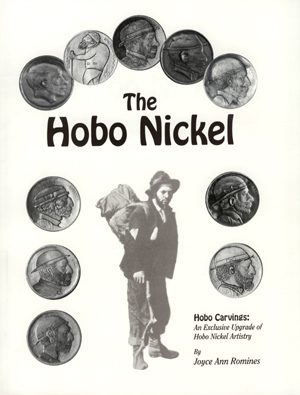

The godfather of the oddball numismatic specialty, Romines literally wrote the book on "The Hobo Nickel" in 1982, documenting for the first time the original works of "Bo," his teacher Bertram "Bert" Wiegand and myriad other hobo nickel carvers whose given names may never be known. In 1996 Romines' wife, Joyce Ann, updated and republished the book.

Now 70 and undergoing chemotherapy treatment, Del Romines "dropped out of all coins 100 percent" several years ago, he said, "primarily because of my health."

Primarily, but not entirely. It was bitterly frustrating to Romines when actual "fakers" — "numis-cheat-matists," he called them — copied coins out of his 1982 book and passed them off as old originals.

But rather than come back around to his purist way of thinking, by the 1990s the hobby had changed. No longer were the best carvers imitating the works of Bo and Bert. They didn't need to. They were talented professional engravers who were using the Buffalo nickel — and other coins, but chiefly the Buffalo — as a blank canvas for their own original creations.

Rather than shun them, the hobby embraced them — and so did the marketplace. Today their coins rival and frequently surpass the original works of Bo and Bert when sold at auction, and collectors are commissioning new, original pieces at prices into the thousands.

It's not that the old masters have been forsaken. It's just that the hobby isn't limited to them anymore — leaving stalwarts like Del Romines behind.

"There are many extremely talented artists out there today who are producing incredible carvings that are gaining a huge following," said Bill Fivaz, an old friend of Romines whose coin photos illustrate both Romines books. "Of course, they have the advantage of modern gravers and implements that the old timers didn't have, but when you see some of the intricate workmanship that's being done on not only nickels but all coins, it is just so impressive. ... They are superbly talented, imaginative, creative artisans who take pride in their work, and rightfully so."

Fivaz is best known as the author (with J.T. Stanton) of "The Cherrypickers' Guide to Rare Die Varieties" and is a member of the Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee, which advises the Treasury Department on new coin designs. It was Fivaz's slide presentation at the American Numismatic Association's 1992 Summer Seminar that led to the formation of the Original Hobo Nickel Society.

OHNS President Archie Taylor said of modern carvers, "They are artists (who) are using their own genre, which happens to be a nickel, and are taking their ideas and are able to put (them) on that piece of metal and bring it to life."

The quality of work being done today "spans the realm" from "just a simple scratching up to the most intricate inlays of gold and silver and copper and diamonds," Taylor said. And that variety appeals to him.

"I believe that there is a coin for everybody to collect," he said. "We have carvers who sell $5 coins. We have carvers who carve $5,000 coins. We have the ability to have any person of any age have a hobo nickel in their hand and be able to afford it."

Ron Landis of Arkansas was the first high-end engraver to enter the field of hobo nickel carving after the "transitional" period of the 1980s.

"We're really going through a renaissance with the art right now," he said, "because with the high prices they're demanding, it's attracting THE best engravers in the country, and the work has never been better."

Fivaz agrees with Taylor and Landis that when it comes to hobo nickels, new or old, "It all boils down to eye appeal."

He cautions against a hasty dismissal of the old masters, however.

"There are a few carvings by Bo that will be in the January 2007 OHNS auction ... that I think may set new records for any hobo nickel, original or modern, so don't discount the workmanship and desirability of the old guys," Fivaz said. "Supply and demand is always the bottom line."

OHNS holds its annual auction in conjunction with the Florida United Numismatists (FUN) convention in Orlando where an "old original" hobo nickel, carved on two sides — a rarity — shattered price records in 2005 at almost $5,000.

Contrarily, at the 2006 show, the highest prices went not to the best Bos and Berts, which were represented there, but to a pair of coins by Steve Adams, one of the best in the business today.

A die engraver and bas relief sculptor in Wisconsin, Adams carved an equestrian theme into a nickel that fetched $2,860, while his whimsical and finely detailed rendition of King Arthur brought $2,750.

In the auction catalog, Fivaz, one of the primary OHNS board-certified "authenticators," called the latter coin "probably the nicest and most intricate modern carvings I've had the pleasure of examining."

Fellow authenticator Stephen Alpert, author of the standard OHNS reference, "Hobo Nickel Guidebook" (2001 and 2005), called the coin "a masterpiece with great eye appeal."

Just as Professional Coin Grading Service and Numismatic Guaranty Corp. authenticate and grade coins on a 70-point scale, the OHNS authenticates and grade hobo nickels on a five-rating scale from "crude" to "superior."

There are two other certified OHNS authenticators: Don Farnsworth and Gail Baker, the ANA's manager of market and brand development, who has been with OHNS since its inception.

Fivaz, who purchased about 500 of the coins he photographed for Romines' first book, knows from handling so many Bos and Berts whether they're authentic.

Romines may not consider the modern carvings "hobo nickels" because they aren't created by "hoboes" (a name for migratory workers who were originally called "hoe boys," not to be confused with bums, who didn't work). But, he acknowledges, the best of the new carvings "are artwork."

His problem with the new pieces is that "there is no history behind them."

You don't want to tell Ron Landis that there is no history to what he is doing.

Landis, 52, is the brains behind the Gallery Mint, known for its replicas of early U.S. and colonial coins in the original alloys. He has been striking medals from handcrafted dies since 1982, when he acquired an old-time screw press and "got hooked" on the ancient coin-making processes. He built a "period" rolling mill, edge mill, intaglio printing press, bellows, furnaces and dies and used them to demonstrate the history of coin making at renaissance fairs across the country.

Eventually he amassed too much equipment to haul around. He settled in northwestern Arkansas and formed a nonprofit foundation to build the Gallery Mint Museum, which will showcase his collection and preserve the technology and techniques used in engraving and minting, from ancient Greece to the Industrial Revolution.

For Landis, carving hobo nickels and encouraging others in the trade is the way to prevent this historic form of craftsmanship from becoming a "lost art."

"Hand engraving is really one of the most important art forms we have," he said. "You couldn't have coins, paper money, seals, postage stamps; even Gutenberg's movable type system couldn't have been made without hand engravers to make the original punches that made the type molds. This is something really worth preserving."

Landis and Romines are like oil and water.

"When he first started (carving nickels)," Romines said, "he was calling them hobos. I had serious talks with him."

Landis, who uses the term "hobo nickel" more generally to denote any altered nickel, remembers the conversations.

"(Romines) was always of the opinion that as soon as Bo died, the art form was dead, period," Landis said. "My stance was, no, the art has never died. The art form has changed a little bit" with the use of modern engraving tools, but even with the "copycats" during the transitional period between the time of Bo and the 1990s, "it was just a continuation" of the technique, he said.

"My whole goal with building this museum of coin-making technology is trying to keep the art form alive. (Romines) was so willing to try to declare it dead that we had a big conflict there. He did not like what I was doing. He accused me of marring history. (I say) no."

It's not as if the modern masters are using space-age trickery to produce high art.

"Ninety-five percent of the work has to be done by hand if you want to get any kind of detail and sharpness to it," Landis said. "With a rotary tool, you just can't get the definition between the device and the field."

Landis goes so far as to question whether the early masterpieces were really the work of the stereotypical hobo in a boxcar with nothing more than a knife or a nail.

"(With) a lot of the so-called original hobo nickels, I can see (evidence of) professional jewelry engraving tools, line engravers, shading gravers and so forth, and professional techniques being used. You can't tell me that guy's a card-carrying hobo. It's more likely he's an out-of-work jeweler."

Old or new — "original" or "modern," in OHNS parlance — the true masters didn't develop their skills in a vacuum. Just as Bo apprenticed under Bert, so do modern carvers learn from their more seasoned contemporaries. In recent years, some of the apprentices have gone on to become masters themselves, with apprentices of their own — perpetuating the art form.

Bill Jameson, for instance, has been carving hobo nickels since 1995 when a co-worker at Goodyear in Kentucky challenged him to make one.

"That first one, I took a nickel and attached it to a table with wood screws. I had some old punches and a hammer. I probably started with 50 cents' worth of tools. It brought $15. Then I just went on from there," said Jameson, known as "Billzach" in the hobo nickel world. (Most OHNS members use aliases or monikers, as did the old hoboes. Fivaz is "Zemo.")

The turning point for Jameson came in 2002 when he enrolled in a workshop taught by one of the top-tier carvers, Sam Alfano. The workshops are held in Kansas by GRS Tools, a leading maker of instruments used primarily in gun, knife and jewelry engraving.

"That's when I really picked up on how to do the ears and the hair," Jameson said. He also became one of the best "field dressers" in the business. The term refers to the way the field, or flat surface of the coin, is tooled.

"I make them smooth from start to finish," he said. "If you get too rough at first, it will stay with you all the way to the end. (I like to) make the field look like it came out of the Mint."

Today, "Billzach" needs a stick to beat away the requests for commissioned work. He still carves the occasional nickel, along a few Morgan dollars that he transforms into replicas of old patterns. He also taught his son, Shane, and his brother-in-law, Phillip Lanmon, his techniques. But lately he is focusing most of his time and talent on knife and gun engraving.

"You've got hundreds of thousands of people out there that would like to have a nice knife or gun engraved. Hobo nickels, probably under 100 people" would spend $500 or more.

Nonetheless, he is determined to break the $1,000 mark for a nickel.

"The best one I've done is $600," he said. "I'm wanting to get $1,000 (for) one, just because I want to (make) a better coin."

The big story at the FUN show this year wasn't the news from the bourse floor.

It happened on a Saturday night in January when Taylor and two hobo nickel carvers, Keith Pedersen of New Jersey and Owen Covert of California, went to dinner.

"We drove 14 miles from the FUN show (and) parked our car in a lit parking lot with a camera in view," Taylor said. "We didn't notice until we had driven three miles to unload everything at the guys' motel. We opened up the trunk and the thing was empty. They knew what we had, because they never touched my breathing machine, they never touched any of our clothes, they took only the bags that had the coins in them."

Gone were approximately 1,000 hobo nickels worth at least $100,000. Taylor lost a collection of 250, including his only Bo and some nickels he had purchased at the OHNS auction that day. Pedersen, a self-taught "weekend" artist who does maintenance on a bridge in New York City during the week, lost about 400 coins representing 2-1/2 years of work. Covert lost his own creations as well as the entire 83-coin collection of carvings by Wabon Eddings.

Taylor, Pedersen and Covert were relatively lucky. Earlier that day, four men with shotguns followed a silver Mercedes from the FUN show and smashed the windows while the driver sat behind the wheel outside a Waffle House restaurant. The robbers popped the trunk and made off with $250,000 worth of merchandise. The driver was uninjured.

That wasn't the last of it. In late February, someone was followed from the Collectorama show in Lakeland, 40 miles from Orlando, Taylor said, "and their car was broken into and their coins were stolen. ... They're still in the area. Whoever's doing it is still here."

There is a lead in the Taylor-Pedersen-Covert robbery and the FBI is involved. No arrest had been made as of this writing.

Hobbyists fear the crime wave will put a damper on coin shows.

"I will not do any more carrying of any coins in any place, any time, anywhere," Taylor said. "I personally will now only ship coins through FedEx or whoever."

Even that might not be safe. Several coins from Heritage auctions in Dallas in January and Long Beach in February were stolen out of Federal Express packages in Seattle in March.

Hobo nickel carving can effectively be divided into three periods, the first being the time of the old original hoboes. The second is the intermediate or transitional period following the publication of Romines' book in 1982 (and his preceding articles in Coin World in 1981), which Alpert refers to as the time of the "early modern artists." The third period is the era of what Alpert calls the "later modern artists" who entered the field after 1992, when the OHNS was organized.

Two transitional-period nickel makers of the early 1980s in particular soured Romines on the hobby.

Alpert writes, "Frank Brazzell of Terre Haute, Ind., ... made about 4,000 hobo nickels a year from the 1980s to the mid 1990s. He died in 1996. Frank used a hand-held power-driven graver to create his hobo nickels, which took only 5 to 10 minutes each to make. Most of his designs are copied from works by Bo that appeared in Romines' 1982 book."

An even more controversial copycat was John Dorusa, a coal miner from Pennsylvania who died in about 1994.

Dorusa claimed to have been taught the craft by Bert and Bo in the 1920s. According to a story published in the Somerset County (Penn.) Daily American in 1983, "Dorusa uses various chisels that he's made from old files. Three of his tools originally belonged to Bert Wiegand, the black hobo who created the first such re-made nickel and taught him the skill." (Bert was white, so right there you know something is wrong, either with Dorusa's story or with the reporting.) "Dorusa, now past 70, was 16 or 17 when he ran into Bert and his friend, George ╬Bo' Washington Hughes, another black hobo, in Indiana," the report said.

"I was touring around, same as they were," Dorusa told the newspaper. "I stopped in this flea market and saw Bert working. ... It took a year, maybe better, till I learned how to do it good."

"Over the years, he's made ╬thousands and thousands' of hobo nickels," the newspaper reported. "He's done a complete set of U.S. presidents, along with self-portraits and pictures of Bert and Bo."

The trouble is, the portraits of Bert and Bo are believed to have been copied out of Romines' Coin World articles and his 1982 book.

According to Alpert, Dorusa "even ╬signed' some of his early Bo copies ╬GH' or ╬Bo.' ... There is no evidence he made any hobo nickels prior to 1980."

Romines told COINage that Dorusa tried to pass of the coins as original Bos and Berts. "He didn't tell (people) he did make them, at first," Romines said.

Not until Romines read him the riot act did Dorusa start singing his coins "JD" or "J Dorusa," Romines said.

Evidently it didn't take long for Dorusa to comply. The 1983 newspaper article clearly states that Dorusa was creating the coins himself and carving his initials into them.

Archie Taylor isn't quite as quick to condemn Dorusa.

"John Dorusa was from Jennerstown, Pennsylvania, a little town that happened to be one mile from where my children lived for 25 years. I basically know and I believe that John Dorusa did have either Bo or Bert at his house," Taylor said.

"I also know that people have collected some of the coins that were in the 2x2 (cardboard holders) that Dorusa originally did. He took Del Romines' first book and would put the page (number)" on the holder that corresponded to the coin he copied "and he marked it that way."

(This writer has a Dorusa coin in an original holder with "P[age] 41-7-" on it and "JD" carved into the hobo's collar.)

One can sympathize with Romines' adverse reaction to the newcomers in the early 1980s when you consider that up to that point, hobo nickels had always been one thing; then he writes his book and people start copying them and passing them off as hobo nickels. He was devastated. "Had the ... first book never been published, the many non-artistically talented fakers and cheats would have had nothing from which to start their scams. This is a regrettable occurrence, and the authors sincerely apologize for any part which the first book may have played," Del and Joyce wrote in the second edition.

By the time the second edition was published in the mid-1990s, it was a different hobby. Collectors still revered the old masters, but they were welcoming talented new craftsmen with open arms — and open pocketbooks.

"I don't see a whole lot of (fakery) going on," Landis said. "Most of the carvers have enough self-respect, they're trying to create their own art and make a name for themselves, rather than trying to fool somebody."

©2006, MILLER MAGAZINES INC./LEON WORDEN. RIGHTS RESERVED.

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Bill Jameson, alias Billzach, studied under prominent carver Sam Alfano and is considered one of the best "field dressers" today

(referring to the way the field of the coin is tooled). He used a wheat pattern common to gun engraving for the rim of the coin above, which sold for $227.50 on eBay in March.

(Photos: Bill Jameson)

Bill Jameson, alias Billzach, studied under prominent carver Sam Alfano and is considered one of the best "field dressers" today

(referring to the way the field of the coin is tooled). He used a wheat pattern common to gun engraving for the rim of the coin above, which sold for $227.50 on eBay in March.

(Photos: Bill Jameson)