Outspoken Educator Continues to Pursue His Goals

By Leon Worden

August 2006

|

| E |

"Look at the coin. The clues are there," says the man, identified in the program booklet as "Mr. Numismatics."

Elizabeth is confident. After all, this isn’t her first Long Beach Coin, Stamp & Collectibles Expo. She enjoyed the "Treasure Trivia" and "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?" games so much the last time that she’s a satisfied returning customer. She knows the "Millionaire" game like the back of—well, like the back of a Nevada state quarter.

"For 50 cents, what type of animal do you see?"

"Horse," she replies quickly.

"Actually they’re wild mustangs, but you’re right," the man says. His grin widens. "Nevada has the largest number of wild mustangs in the United States."

Elizabeth has survived round one. She can quit now and can keep a bicentennial Kennedy half dollar attached to a card that tells its history. Or she can risk it and go for the coin with six zeroes on it — a 1 million lira inflation coin from Turkey.

She takes the risk. "According to the coin, Nevada is called the ‘what’ state?" She looks. "The Silver State." "For 100 [cents, in the form of a Sacagawea dollar], what is the state capitol of Nevada?"

Not all the answers are on the coins. The tougher ones you have to know. Elizabeth knows. She studied state capitals at Friends Christian School in Yorba Linda, California, where she is in the fifth grade.

"Carson City," she replies.

"Are you sure?" The man teases her. First instincts are correct 70 percent of the time, he says. He wants her to know.

Under the rules of the game, she can get some help from two other people. Sitting with her are her dad, Doug, and her brother, Joseph, 8. "You’ve got two lifelines. Do you want to use them?"

"No. It’s Carson City."

Right again. "What is capping those mountains?" "Snow." "For 10,000, what are the horses doing?" She hesitates. "They’re running." "They’re galloping," he corrects. Close enough.

"Are the questions getting tougher?" he asks. "That’s what they’re designed to do, to make you think." The 11-year-old nods. "Do you want to stay with Nevada?" "Yes."

She can do this. She’s been collecting coins for two years, and already she has all of the 50-state quarters that have come out so far — five new designs per year since 1999.

"See the plants?" he asks. Elizabeth didn’t know this was coming. But if you know Mr. Numismatics, you’d be expecting it. His doctoral degree is in plant taxonomy and he taught botany at UCLA for more than a decade.

"What type of plant, or brush, is pictured on the coin?" Elizabeth misses the clue. Dad throws her a lifeline. "Sagebrush," he suggests. She agrees.

"For 500,000, Nevada is home to what percentage of the wild mustangs in the United States?" Uh-oh. Maybe she should have quit and walked away with the Sacagawea and another high-denomination foreign coin as a consolation prize. But not Elizabeth. She presses on.

The lifelines are of no use. Mr. Numismatics offers her a multiple choice. She settles on 50 percent. She’s right. There’s no stopping her now.

"For 750,000, what famous silver and gold mine, or lode, was established in the Virginia City area and led to the establishment of a U.S. Mint in Nevada?" Lifeline from Dad. "The Comstock Lode."

Here it comes. "You could be our first millionaire today," says Mr. Numismatics, beaming. "Either way, I’m proud of you."

"For $1 million, the first mention in a Nevada journal of the wild mustangs being in Nevada dates from what year?"

She doesn’t know. Neither does Dad. (The answer is 1820.) "Remember," the man says, "you can switch the question out, but it won’t be from Nevada." He hands her a Kansas state quarter. "It’s just right or wrong. I’m not going to ask you how many blades of grass there are. There are 1,861. [They represent the year Kansas entered the Union.] I’m not going to ask you how many petals are on the sunflower. A sunflower has no petals. [Each sunflower "petal" is actually a separate flower.] You’ve got a 50-50 chance. Is the buffalo male or female?"

She guesses correctly and walks away with the Sacagawea dollar, the Turkish coin and a $2 United States Note from 1953 with a red seal.

Victory.

And the man didn’t even make her count the 82 ocean ripples on the Rhode Island quarter.

"My goal is to entertain and educate young people about collecting and studying coins, to get them captivated," says Walter A. Ostromecki Jr., who has filled the role of "Mr. Numismatics" at Long Beach since 1987 — three shows per year, missing only three in that time.

"[Youth] is the future base for the hobby," he says. "That’s where our future collectors come from, our future dealers, and our future leaders."

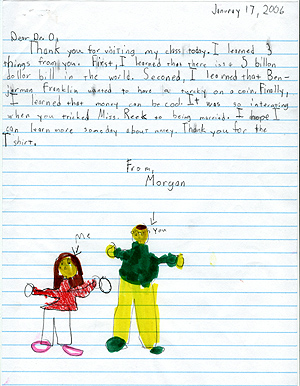

Ostromecki repeats the performance in one form or another at 30 shows a year inside and outside California, and innumerable times throughout the year at schools in the Los Angeles area. He recently helped developed youth course materials for the Canadian Numismatic Association.

"No longer are the kids being dragged [to coin shows]," he says. "There is something they can do when they get there. I’m hoping to make it an enjoyable memory for them so it’s a hobby they’ll want to stay involved with or come back to later on."

"Do you remember in February [in Long Beach]?" he bubbles. "We had over 200 kids."

Ostromecki is quick to credit the success of the youth programs to a support network that ranges from the U.S. Mint, which provides teaching materials and literature; to Gerald Singer of The State Quarter Co. in Vallejo, Calif., who donates a bottomless supply of coins as giveaways; and many hobby organizations and dealers in between.

As the ranks of young numismatists in Long Beach have swelled, colleague Darryl Crane of the Full Step Nickel Club has taken over the operation of the Treasure Trivia game. Kids collect clues (and souvenirs) from dealer tables on the bourse floor for a shot at winning "pirate treasure." Crane dresses the part.

"What is a pirate’s favorite subject in school?" Crane calls out. "Arrrgh-rithmetic!"

"The youth programs add a lot," said Santa Barbara rare-coin dealer Ron Gillio, owner of the Long Beach expo. "They bring new kids into the hobby, and parents can spend time with their kids while they see the show."

Ostromecki will bring the Treasure Trivia game back to the Tucson International Coin & Stamp Show on Oct. 28-29-30.

"We’ll have 1,000 kids over the weekend," said Karin Lawrence of Eagle Eye Rare Coins. "Walter is wonderful. The kids just flock to him. They love him. … You’ve got to start them young, and this gets them to see it’s fun."

Except for occasional air and room fare — Tucson will cover his hotel bill, Lawrence said — Ostromecki offers his services gratis. It’s a hobby and a passion. Or rather, the convergence of two passions: numismatics and education.

In college, while pursuing a teaching career, Ostromecki got hooked on botany thanks to some enthusiastic instructors who made it interesting. He taught at UCLA until he divorced from his wife in 1991 and was left to raise two children on his own.

"I had to quit to take care of the kids," he said. "The kids were young at the time. I had the custody and all of the responsibility. I took time off. I had enough to retire even then."

But education drew him back. By the late 1990s he was on a leadership team that split the monolithic Los Angeles Unified School District into seven regions — regions that never really achieved the autonomy that was envisioned, he said. Today his 9-to-5 job is to train principals and assistant principals when they’re first assigned to an L.A. Unified school in the San Fernando Valley.

|

"I’m an educator. As long as I can educate, that makes me happy," he said. "If I can entertain and enlighten and get kids to smile — that to me is the reward."

He tailors his school programs to grade level. Third- and fourth-graders are the youngest he works with. "I like to sit them on the floor. Kids like to be in a circle. I’m just Walter. They get a chance to see, feel, touch, hold whatever it is, pass it around.

"I also tell them stories using money of the odd and curious." He pulls out something that looks and feels like a wire bracelet. "What animal was it from? Ever been to a zoo? Ever seen an elephant? Take a look down along his legs. Down at the very end, there’s a little grass skirt of hair, like metal wire, to protect the elephant’s leg when he cuts through the underbrush. As they break off, the Ethiopian tribes would pick them up and string them together and wire them into bracelets. They got the term ‘elephant money.’ The kids go, ‘Eww.’"

His coin programs reinforce their book-learned lessons. "Boys against the girls. A fun rivalry. Who’s the best mathematician? OK, what’s this one? Half cent. That’s a fraction. Look at some of our earlier currency items. Here. One of our early continental dollars. What’s the value? Two-thirds of a dollar. See? Now you know why you’ve got to learn fractions today in school."

He challenges high-schoolers to think. "You can teach a whole history lesson through what’s on the state quarters."

He passes around a Virginia quarter. "Tell me the names of those ships. What are [the students] going to say? ‘The Nina, the Pinta and the Santa Maria,’ because history tells them, three ships on a coin, Columbus. They all agree that’s the right answer. Now, when did Columbus discover America? 1492. Now, what’s on the coin? The coin tells what it is, for Jamestown colony. ‘Oh, well then it’s the Mayflower.’ See, now we’ve got them thinking. I’ve got their attention. It’s not easy to keep with high schoolers. Believe me, it’s tough. I’ll give you this golden dollar if you can tell me the name of one of those ships. I’ll give you a clue. One has the same name as one of our space shuttles. And I’ll say no, it’s not Endeavor, because that was Capt. Cook’s ship in Hawaii in 1777-78. ‘Discovery’ is what I’m looking for.

"Now you’ve discovered the wonderful world of coin collecting, but you’ve also discovered how much more fun dates, names, places in history can be as taught through coins."

"The girls call it torture," he says. "They’ll walk off and they come back. They want to know more."

"Look at the Delaware quarter. They’re gong to say, ‘That’s Paul Revere,’ because history tells them a man on a horse — so I tell them about Caesar Rodney. His diary tells us he went through 11 horses to make that trek, and took two days to do it. What was so important about Caesar Rodney getting to Philadelphia? What was at stake? And then I take a British coin. Here is what was at stake. See if they can make a connection. Instead of having Abraham Lincoln on a cent, we could have Queen Elizabeth. ‘Oh, yeah, that Constitution thing.’ No, the Declaration of Independence."

It wasn’t the coins or even the stories that kept young Walter coming back to West Valley Coin Club meetings in the 1950s with his mother, Agnes. It was the jelly donuts.

"They had the biggest and best jelly donuts of any place I’d ever seen — and I could have a second one," he remembers.

Dealer Murray Singer took him under his wing and paid his first-year dues. Later, in 1975, Singer would get him involved in his first American Numismatic Association convention. Nona Moore put him to work at the ANA’s registration desk in 1981. He started writing for Margo Russell at Coin World, often about women in numismatics, and he team-taught a writing course at the ANA’s Summer Seminar with longtime ANA executive director and Numismatist editor Ed Rochette. In 2000, while serving as the national coordinator for the ANA’s Club Representative Program, he received the ANA’s Exemplary Service Award.

Locally, he was the youth program director for the Numismatic Association of Southern California before becoming its president in 1991. He stayed active in the West Valley club until it dissolved; it met in bank buildings that kept getting taken over by other banks. Today he is vice president of the Verdugo Hills Coin Club in Los Angeles where he organizes monthly programs and youth auctions at VHCC’s coin shows.

|

"Kids now have so many distractions," Ostromecki said. "I went out and played army, went out and got dirty, made a tree house. That was my fun in the ‘50s-‘60s. I rode my bike down to bid boards."

"Kids don’t do that anymore. I think that excitement is gone. If we don’t plant that seed now, my concern is, we won’t have a future hobby base that’s willing to join coin clubs or national and regional associations. Those are dwindling at an unbelievable rate. Here in L.A., we used to have 102 coin clubs at one time. Today there are less than 30."

"The clubs have just fallen off because they haven’t changed the way they do business. The shows, too. That’s why I don’t like cliques. They do things the old way. They cannot bring themselves into modern times."

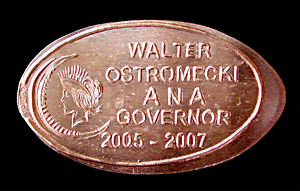

Ostromecki wanted to change what he perceived to be "old ways" at the national level in 2005 when he was elected to the ANA board on his third try.

"[The ANA’s] charter is for education. I thought my background could enhance and build on educational programs that we could develop. I felt we should piggyback and work with the U.S. Mint on the H.I.P. [youth] program and help promote that, since they’ve already written the booklets for K1-K6. … I thought I could make an impact and be a voice for the collector."

He never got the chance. Elected to a two-year term in late July, the board voted 7-0 to remove him Oct. 14, two and half months later.

The propriety of his ouster has been debated in the numismatic press and has polarized ANA members. Ostromecki’s outspokenness on two key issues apparently violated rules of confidentiality and board conduct.

One matter involved the naming rights to the ANA’s Money Museum, which the board ultimately decided to name for Rochette in return for a $500,000 donation from longtime hobby publishing leaders Chester Krause and Clifford Mishler and an anonymous third benefactor.

|

Mishler, who thought the deal to use Rochette’s name already had been approved, objected to continuing talks with other potential donors and sent e-mails to all the board members asking for an explanation. Only Ostromecki responded, and he expressed his displeasure with what was happening (a process which the ANA later halted).

The other matter involved the prior board’s decision to partner with a for-profit coin show in Las Vegas. Ostromecki said there were "some unhappy individuals who wanted that [decision] revisited." In an op-ed piece, Horton said Ostromecki didn’t object to the Las Vegas partnership during the call, even though he had "encourag[ed] members to voice their opposition." Ostromecki said the speakers at a board meeting were "laughed at and mocked afterward." Horton called the allegation "an outright lie."

"For the two months he was an ANA board member, [Ostromecki] was constantly dishonest with us, and that dishonesty destroyed any level of trust the board had," Horton wrote.

"Maybe I was a threat to somebody," Ostromecki said. "I don’t play by their rules. I do things differently."

When elected in July, Ostromecki wrote an article outlining his ideas for expanding the ANA’s educational programs — without first vetting it with the ANA leadership. The article appeared in early October. "That was a no-no," he said.

"The thing that bothers me is that the board [is expected] to do and say nothing," Ostromecki said. "It seems that only the president speaks for all of them. That gives me the impression that the board members are there as window dressing."

Ostromecki shrugs off the ordeal and plans to rerun for the ANA board next year, which he can do.

Don’t expect him to stop speaking his mind.

Oh, and about the buffalo on the Kansas quarter. It’s male.

"I know that because the artist told me so," Ostromecki said. "He looked at Black Diamond [the bison on the Buffalo nickel of 1913-1938], which was male … and they lengthened the horns. Male buffaloes have longer horns."

©2006, MILLER MAGAZINES INC./LEON WORDEN. RIGHTS RESERVED.