Space-age technology secures a controversial display

By Leon Worden

November 2006

|

| I |

Surprise: It isn’t entirely fictional. The graphic image of a "transparent aluminum" molecule in the movie was loosely based on the structure of Lexan, made in the here-and-now by General Electric. It was lightweight and yet strong enough for the Enterprise crew to transport two humpback whales across time to an Earth that doesn’t yet exist, and in August, its real-life equivalent was perfect for encapsulating 10 coins which, in the words of Acting U.S. Mint Director David Lebryk, "should not exist."

But the coins do exist. They very much do.

On Aug. 16, the public got to see them for the first time when the U.S. Mint extracted them from the bowels of Fort Knox and unveiled them during the opening ceremony of the American Numismatic Association’s summer convention in Denver.

What made them special wasn’t their gold content, or their certain beauty, or even their rarity. Plenty of coins are one-of-a-kind. Not these. What made them special were four little numbers to the right of Miss Liberty’s upraised foot: 1-9-3-3.

Yes, these were the 10 coins now familiar to COINage readers: The 10 1933 Saint-Gaudens double eagles, or $20 gold pieces, that the Mint seized — the word in the official press release was "recovered" — from the heirs of Israel Switt, a Philadelphia jeweler who allegedly possessed 25 of them in the 1930s.

"These gold pieces were never issued as coinage and should never have left the United States Mint at Philadelphia," Lebryk told the crowd in Denver as the television cameras rolled — more cameras than ever before at an ANA convention.

Lebryk described the financial crisis that gripped the nation when Franklin Roosevelt took office in 1933. He said Roosevelt banned the private possession of gold before any 1933-dated $20 gold pieces had been issued, and that an unknown number of them "were illegally spirited out of the [Mint]."

Twenty of Switt’s contraband coins are accounted for. Eight were confiscated and a ninth was willingly surrendered in the 1950s; all nine were destroyed. A tenth was involved in a legal dispute that led to its sale at auction in 2002 for $6.6 million (with buyer’s fee, $7.59 million). Now come another 10, voluntarily delivered to the Mint for authentication in 2004 by Switt’s daughter — but not voluntarily returned to her.

Where are Switt’s other five coins? Perhaps in Europe, far removed from the watchful eye and authority of the U.S. Secret Service. There have been several reported 1933 double eagle sightings. And Izzy Switt might not have been the only source.

Switt’s daughter Joan Switt Langbord, 77, and her sons, David and Roy Langbord, are fighting to repossess their 10 coins. Their New York lawyer, Barry Berke, filed a demand for the coins’ return. The Treasury Department rejected it. In May he filed a claim for monetary damages. As of this writing in late August, nobody is telling how much money the family is seeking, but it is safe to assume the figure is based on a guesstimate of how much the coins would fetch if 10 of them came on the market. If the Treasury Department won’t cut a deal by mid-November, it’s off to court.

The Mint decided not to wait for the challenges to its ownership to be settled before presenting the coins for all to see — to the irritation of Berke and the Langbord family.

"It is our position that the coins are not the Mint’s coins to display," Berke said in an Aug. 11 telephone interview. Neither Berke nor the Langbords attended the ANA convention.

"The Mint’s attempt to gain some public relations advantage in the pending legal dispute over the Langbord family’s ten 1933 double eagles by publicly ‘unveiling’ and displaying the coins is indicative of the Mint’s arrogant and lawless approach to these numismatic treasures," he said in a prepared statement, calling the seizure "illegal[]."

|

"I think that’s a little tacky," D’Ambra said of the Mint’s decision to display the coins, after he showed them to a friend’s children. "I think we need to settle who the rightful owner is before anybody goes around displaying them."

Others were simply happy for a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see the coins — although Mint spokeswoman Becky Bailey said the government "hope[s] to do this again and again."

"They were just awesome," said Karen Haubenchild of Castle Rock, who waited in line to show the coins to her 7-year-old twins, Sara and Matt. "Just the thought that it’s the first time it’s publicly being seen, and we’re the public seeing it, was pretty cool."

"They were phenomenal," said Vivienne Peterson of Ogden, Utah. Her husband, Ruatt, wasn’t sure they should be returned to the Langbords. "That’s a strange story, how they got out of the Mint," he said. "I’m thinking no, probably not, but that’s yet to be told."

Visitor Walter Figel, also of Castle Rock, had just finished reading a book about 1933 double eagles that his daughter gave him for his birthday. He thinks the 10 coins should be legal to own.

"The contention is that a person substituted other double eagles for these, which means the taxpayer lost nothing," he said. "They got an ounce of gold for an ounce of gold. All they lost was the date number on the front of the coin, which meant nothing to the Mint."

Figel was pleased to see them preserved. "I was afraid they were going to do something stupid like destroy them, like they did with the other nine."

The Mint decided as early as August 2005, when it announced their existence, that it wasn’t going to melt the Langbord 10.

"The United States Mint will assess the best way to use these historical artifacts, including possible public exhibits, to educate the American people," the Mint said at the time.

|

"I was thinking more for our museum," Cipoletti conceded, hoping the coins could be displayed long-term at the ANA’s Edward C. Rochette Money Museum in Colorado Springs. With the unresolved legal issues — which the ANA is "not going to get involved in," Cipoletti said — and the simple matter of securing the nation’s most controversial coins, it wasn’t going to happen.

But then, "a week or so later," Cipoletti said, "I got a call saying, ‘What would you think about having the double eagles come to Denver?’ I jumped on that opportunity."

That was July 27. The convention was scheduled to open Aug. 16. The ANA had three weeks to work out the logistics, guarantee security, and design and build a display case. The role of "chief engineer" fell on Douglas Mudd, the ANA’s curator of exhibitions, who would have to work nearly as fast as his fictional "Star Trek" counterpart.

"We had some very good people working with us," Mudd said. "Our fabricators are fabulous. That’s what made it possible. Normally it’s not something you can get done, and they had just over two weeks by the time we contacted them and said, ‘We really have this important project; can you do it for us?’"

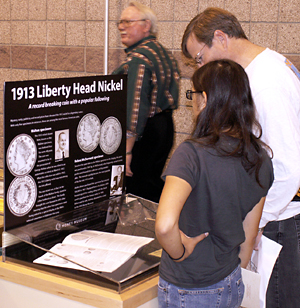

Mudd and his Money Museum crew "created a display that’s designed to allow people to get up close to the coins and really see what we’re talking about."

"It was a little bit difficult, in that we’ve got 10 [coins]. Two or three you can do, but 10 is unusual," he said. "We’ve got a circular Lexan ‘sandwich’ with a Plexiglas center, which has holes laser-cut to the exact size of the coins. They’re sandwiched between Lexan, which is bulletproof, something that can’t be broken or shattered. The main point is to make sure that nobody can grab it and run off with it."

|

Built at a cost to the ANA of about $5,000, the exhibit included graphics and text that told of Roosevelt’s gold ban and the illicit nature of the coins. One thing the 9,237 convention visitors didn’t see was any mention of the Langbords.

"Basically that wasn’t one of the options," said Mudd, who wrote the text but had to have it approved by the government.

"The Langbord family vehemently objected to the language that was used to describe the coins," said Berke, particularly "any aspect that suggested that they were stolen."

"We asked for an opportunity to weigh in [beforehand], and we did submit comments," Berke said. "We were told that the language used was the language of the United States Mint."

As the fabled double eagles drew long lines and attracted wide media attention, some other fabulous and even rarer coins — superstars of previous shows — sat just feet away, begging to be noticed. But one owner, Steven Contursi of Rare Coin Wholesalers in Dana Point, Calif., wasn’t complaining.

"It’s always great to see great numismatic properties come out on display. That’s exactly why we display the coins that we display — because I think it’s important for people to see these coins," said Contursi, who brought his 1794 Flowing Hair silver dollar — the finest known and possibly the first U.S. silver dollar — and his unique 1787 Brasher Doubloon with the designer’s initials on the eagle’s breast, the first gold coin of distinctly American design.

|

From the standpoint of their importance to American numismatic history, they probably are. But if the 1933 double eagles can attract visitors to the show, Contursi is happy.

"I think everybody is really pleased with the fact that we’re driving traffic [to the convention]," said Cipoletti. "When you walk in, [the double eagles] may be the exhibit that people come in to see first, but when they walk in and see what the Smithsonian has put together and see the 1913 Liberty Head nickels, they’re amazed and awed at what we have here on display."

Who Let the Saints Out?

It has been nearly 60 years since the status of the 1933 double eagle has been decided at trial. Just how did the coins escape the Philadelphia Mint? And did they do so legally?

Theories abound. Facts are scarce and subject to differing interpretations. Today it is almost a matter of faith — the Treasury Department on one side, holding dearly to a 1947 federal court determination that the coins were stolen government property, and many numismatic historians on the other side, clinging to the belief that the judge didn’t have all of the pertinent information in 1947.

Indeed, there have been new discoveries of documents that have yet to be interpreted by a modern court. The opportunity almost came in 1996 when Barry Berke burst onto the numismatic scene as the attorney for Stephen Fenton. The London coin dealer had been arrested in an old-fashioned Secret Service sting at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City when he tried to sell a 1933 double eagle to Kansas City dealer Jasper "Jay" Parrino, who was also arrested.

The government quickly dropped the criminal charges, but the forfeiture proceedings never went to trial. On the eve of jury selection, the government agreed to auction Fenton’s coin and split the proceeds with him, 50-50.

If the government had a clear-cut case, why settle?

Alison Frankel, a senior writer for The American Lawyer and author of a new book, "Double Eagle: The Epic Story of the World’s Most Valuable Coin" (W.W. Norton & Co., 2006), has a theory. She speculates that the government would have had a difficult time convincing a jury that it hadn’t legitimized the coin in 1944 when it approved an export license allowing a 1933 double eagle to travel to Egypt.

Although never proved, the Fenton double eagle is widely believed to be the same coin once owned by Egypt’s King Farouk. It came to Fenton through an intermediary who claimed to have received it from relatives of an Egyptian army officer who helped overthrow Farouk in 1952.

|

"Moreover," Frankel wrote, "who would testify for the government at the trial?" All of the witnesses were dead — and according to Frankel, under the rules of the court, the government would need a live witness to enter certain documents into evidence.

Even though the settlement agreement in the Fenton case doesn’t identify Fenton’s coin as the Farouk coin, the "export license" argument wouldn’t work in the Langbord case. The export license covered one coin, not 10.

Some argue that the export license is and always was irrelevant.

"The export thing had nothing to do with anything," said Jay Parrino, Fenton’s intended buyer. "The export thing was simply a way for them to save face."

"Mr. Fenton’s attorney found documentation on Treasury stationery where people bought these [1933 double eagles]," Parrino told COINage earlier this year. "When they located this, it left them nowhere to go."

While it is not apparent that the documentation was quite that black and white — and Berke does not discuss specific evidence — certain papers surfaced that relate to a provision of the 1873 Coinage Act still in effect when the first 1933 double eagles were coined. Under the act, it was lawful to walk up to the cashier’s window at the Philadelphia Mint and exchange gold bullion for a like amount of gold coin.

A brief chronology is in order. The last official gold shipment to the Federal Reserve banks left the Mint on Sunday, March 5, 1933. On March 6, Treasury Secretary William H. Woodin ordered Mint Director Robert J. Grant not to "pay out" any more gold. Grant passed down the order to his subordinates with the proviso, "This does not prohibit the deposit of gold and the usual payment therefore."

No 1933 double eagles had yet been minted. Thinking the ban would be temporary, the Mint started pounding out double eagles by Wednesday, March 15. Not until three weeks later, on Wednesday, April 5, did Roosevelt’s executive order prohibiting the private ownership of most gold coins take effect (there were exceptions).

An avid coin collector himself, Woodin was allegedly seen in possession of several 1933 double eagles, which continued to be coined until May 19.

In theory, for three weeks it would have been legal to walk up to the cashier’s window and exchange gold bullion, or even older $20 gold coins, for 1933 double eagles. Izzy Switt’s associates had been known to do just that in the past.

Did they do it in March 1933?

No, said Daniel P. Shaver, chief counsel to the U.S. Mint. "There are very specific records," he told COINage, "and there is no record of any gold being paid out. An exchange would have been a payout … Paying face value to the cashier results in the issuance of gold, and … the Mint was ordered not to issue any gold."

|

In 1996, Berke hired prominent numismatist and author Q. David Bowers to help him with numismatic research. Additionally, Berke’s conversations with coin consumer advocate Scott A. Travers led him to Robert W. Julian, an expert in Mint history.

Julian sifted through stacks of government documents and found a letter unknown to the 1947 court that clarified matters for a potential Mint customer.

Dated March 15 — the same day the first 1933 double eagles were recorded in the Mint’s books — the letter advised Lewis Froman of Buffalo, N.Y., that he could deposit gold bullion directly at the Mint in exchange for gold coin. A transaction involving gold for gold was permissible, Acting Director Mary M. O’Reilly wrote to Froman in Grant’s absence, because it "neither increases nor depletes the stock of gold in the Treasury."

No records are known to indicate that Froman or anyone else took advantage of the opportunity.

"It would have been legal," said Julian, "though a minor contravention of Treasury regulations, to exchange gold coins without a formal record being kept. This is the way the 1933s could have legally left the Mint."

Bowers agrees. "The [Froman] letter is critical to understanding how the mints were operating in March 1933," Bowers states in "A Guide Book of Double Eagle Gold Coins" (Whitman Publishing LLC, 2004). "Under Mint practice dating back for generations, coins in the hands of the Mint cashier could be paid out without any further special instructions."

Bowers and Julian draw a distinction between the ban on paying out gold coins to the Federal Reserve banks and the exchange of coins at the Mint itself.

"While at the time the Treasury might not have been actively paying out $20 pieces or other coins for paper money, it seems quite certain … that someone trading like-for-like could have obtained such pieces," Bowers writes. "[T]he cashier at the Philadelphia Mint for years sold coins at face value to visitors. … [N]either Secretary Woodin nor anyone else would have objected if someone had brought an earlier-dated double eagle to the Mint and requested a 1933 coin in exchange."

Moreover, according to Bowers, while the 445,500 1933 double eagles were awaiting their 1937 meltdown, "not much care was paid" to their whereabouts. "On occasion, loose double eagles of unknown dates were seen strewn around the vault floors and, sometimes, no one knew where particular coins were being kept," Bowers writes, citing "Treasury Department internal correspondence reviewed by [Bowers] in 2001."

Indeed, not until 1944 did the Treasury Department get the idea that there was anything wrong with the private ownership of 1933 double eagles. Treasury officials couldn’t easily go back and ask Woodin. He had been dead for a decade.

Frankel is unconvinced of what she calls the "innocent exchange theory." While signing books in Denver, she told Julian she has doubts about it.

Without even cracking open her book, her readers are steered in a different direction. The dust jacket identifies the Fenton coin as having been "stolen from the U.S. Mint." It is the same conclusion the Secret Service drew in 1944 about all 1933 double eagles, forming the basis of the precedent-setting 1947 court ruling.

Frankel notes that on Feb. 20, 1934, several hundred double eagles that had been sent for assaying the previous year were returned to the Mint cashier’s office. A month later, there was a new Mint cashier: George McCann, who would be imprisoned less than a decade later for stealing silver coins from the Mint.

"Around the time McCann was promoted to Mint cashier, he began playing the stock market," Frankel writes. "For the next three years, the remaining 1933 double eagles were in his care. … Beginning on February 6, 1937, McCann supervised the transfer of bags of 1933 double eagles … to the melting room."

"On March 18, 1937, the Mint was able to report that all of its 1933 double eagles had been melted down into gold bars. But they hadn’t. On February 15, nine days after the meltdown commenced … Israel Switt sold a 1933 double eagle to Philadelphia coin dealer James Macallister for $500."

Frankel notes that Macallister later called Switt "a gold coin bootlegger," and she reports that Switt operated a "back-room trade in illicitly hoarded gold."

From a timing standpoint, the coincidence of Switt’s first sale of the coins only nine days after McCann would have handled them seems stronger than the relationship to their manufacture four years earlier.

Then again, the first 1913 Liberty Head nickel didn’t come out of hiding until 1920, seven years after it was presumably made.

Ultimately, the fate of the Langbord 10 might depend on where a judge decides to place the burden of proof. Prove they were stolen? Or prove they weren’t?

And what says the only private individual in modern times to have profited legally from the sale of a 1933 double eagle?

"It would have been an interesting trial," said Stephen Fenton, who "absolutely" believes the coins were lawfully released from the cashier’s window at the Philadelphia Mint in 1933. "I think it would have been OK with or without [the export license]," he said.

The pleasant, soft-spoken Londoner is a man of few words when it comes to 1933 double eagles. He quietly manned his Knightsbridge Coins booth in Denver, half a convention floor away from the armed guards and the bulletproof display case with its 10 new headaches.

At least this time, they are someone else’s headaches.

|

©2006, MILLER MAGAZINES INC./LEON WORDEN. RIGHTS RESERVED.