State Quarter Artists Speak Out About Contest Rules

By Leon Worden

COINage magazine

December 2005

| A |

"A special, special thank-you to Garrett Burke, who is the one that came up with the spectacular design," Schwarzenegger told the crowd that gathered for the unveiling in January. "Again," the governor repeated, with then-U.S. Mint Director Henrietta Holsman Fore at his side, "let's give him a big hand for his design."

Garrett Burke's initials do not appear on any U.S. coin, including the California quarter, and they probably never will.

|

Nancy Miller was upset when nobody mentioned her husband's name during the ceremony, and if you view the official write-up of the event on the Mint's Web site, it's as if he wasn't even there.

But the Mint didn't copy Butler's name into its age-old annals of coin artists. In fact, like every other state quarter issued since 1999, those half-billion Florida coins credit someone other than the original designer as their creator.

Because it didn't actually solicit finished "art" from the general public, the Mint says. It merely solicited "concepts" from the various state governors, to be executed by the Mint's in-house sculptor-engravers. How the governors decide what should go on their state quarter, and whether they encourage their citizens to submit drawings at all, is up to them.

"Some states have chosen to publicize [the identity of] their artists, some haven't," said Mint spokesman Michael White.

At the end of the day, the Mint sculptor-engravers who mold the plaster models are the people who get their initials on the coins and their names in the record books.

"There's always an issue of managing expectations," said Mint attorney Jean Gentry. "When [a state] has artwork developed for a quarter, there's always the possibility" that people will get the idea that the original concept artist will be credited as the coin artist.

If this approach seems bizarre, or if it seems disingenuous toward hundreds of professional artists and thousands of "regular folks" who entered state-quarter design competitions, or if it seems Machiavellian on the part of government sculptors who get to take credit for coins that depict other people's concepts, it has been called all of those things.

"The Mint engravers hijacked the state quarter program to get their initials on the coins," said Paul Jackson, whose concept was selected by then-Gov. Bob Holden and his wife, Lori Hauser Holden, for the 2003 Missouri quarter. Jackson, 37, is an accomplished watercolorist whose art hangs in the state capitol and the governor's mansion.

"I'm ticked off that 3,300 people [in Missouri] were given a false promise that led to a contest you couldn't win," he said. "Why would [outside artists] want to turn in their work if they're basically a mill to steal from?"

Gentry said outside artists with winning designs know the rules going in, and agree to them in writing.

"Any artist who participates in this program [signs] the same standard release," she said. "In that release it states that 'I waive all moral rights,' which means they are waiving any and all claims for attribution [or] credit. If they do not want to participate because they are concerned they will not get the kind of credit that they think they deserve, then that's the obvious answer: They don't participate."

Jackson is the most vocal critic among the uncredited state coin artists but not the only one.

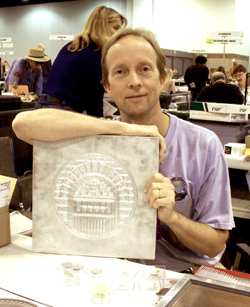

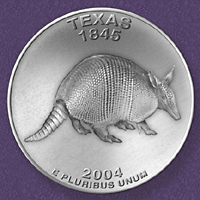

"What upsets me the most," said Daniel Miller of Texas, "[is some of the] Mint artists. I mean, they deserve some credit for taking a two-dimensional design and sculpting it into clay. That's an art. But it upsets me that they're selling their signatures to coin collectors and making good money doing it."

|

ICG told The Associated Press that its "Signature Series" coin artists are paid a signing bonus and a percentage of each sale for a total amount "in the thousands." Cousins and Rogers were neither the first nor the last. Today ICG is marketing coins encapsulated with the signature of Elizabeth Jones, the Mint's last chief engraver (from 1981 to 1990). There is no dispute, however, than Jones designed these coins.

It's not as if the Mint has never put outside artists' initials on coins, even when a Mint sculptor executed their designs. In 1973-74, the Treasury Department conducted one of the most celebrated coin design competitions in history. It invited the entire nation, from school children to professional artists, to submit designs for the reverses of the Washington quarter, Kennedy half-dollar and Eisenhower dollar in celebration of America's 200th birthday.

Eventually, 12 semifinalists were thinned down to three: Jack L. Ahr's Colonial drummer boy for the quarter, Seth G. Huntington's Independence Hall for the half dollar and Dennis R. Williams' Liberty Bell superimposed on the moon for the dollar coin. Each got $5,000, oodles of publicity — and his initials on the coins.

In 2001, Ahr, Huntington and Williams got together for a 25th reunion. The guest of honor was the "Bicentennial president," Gerald R. Ford. The Professional Coin Grading Service (PCGS), a grading industry leader, encapsulated the four men's autographs with silver proof versions of the coins. The three-piece "Presidential" set sells for $1,250 today; the "Artist Reunion" set, without Ford's autograph, goes for $500.

A more recent example of "outsider" attribution: New Mexico sculptor Glenna Goodacre submitted the winning design for the Sacagawea dollar coin obverse. Released in 2000, the coin bears her initials, "GG."

The Mint paid Goodacre in the form of 5,000 specially produced Sacagawea dollars with a prooflike finish. ICG encapsulated all 5,000. She sold 3,000 for $200 each and kept the rest. There is speculation among some hobbyists that Goodacre's profitable marketing of these coins has made the Mint even more wary of crediting outside artists with coin designs.

"That was an exception," said Gloria Eskridge, chief of sales and marketing for the Mint. "She actually did the sculpt on that [coin]. On all the quarters, our engravers do the sculpting."

The legislation that created the 50-state quarter program gave Treasury Secretary Robert E. Rubin sole authority to establish the design selection and approval process. It authorized him to include "participation by state officials, artists from the states, engravers of the United States Mint and members of the general public," as he saw fit. It didn't specify who should get credit on the coins.

A 1997 feasibility study by the accountancy firm of Coopers and Lybrand (later part of PricewaterhouseCoopers) contemplated different design methodologies the company felt were consistent with the legislation.

"First, the federal government can control the design process and receive consultation and advice from state officials on preferred content," the firm said in reporting its findings. "Second, states can control the entire process with less initial involvement from the Department of the Treasury."

Federal control, whether using Mint artists or conducting a centralized, nationwide design contest, would ensure "coinable" designs but might give the appearance of too much federal intrusion into a "state" coin program, the study concluded.

A state-run process, on the other hand, would give people "more sense of ownership [in] the overall program, which would further generate excitement." The downside: Judging could be cumbersome and some designs might be "unsuitable for the nation's coinage."

Rubin decided to empower (and obligate) the states, rather than have design concepts start with Mint artists or with a centralized design competition · lư the Bicentennial and Sacagawea programs.

"The main thing that drove that was that the legislation was passed very late in the year," said White, the Mint spokesman. President Bill Clinton signed the coin bill on Dec. 31, 1997, and the first quarter was due in January 1999.

"Basically, we had a year to get the entire program going," White said. "We had to forge ahead and develop the process within that year and get it approved by the Treasury Department."

Still, when a governor selects a design that's based on the work of an identifiable artist, why not credit the artist on the coin?

"We're trying to keep consistent across the 50 states," said Eskridge. "This is a 10-year program, and we were trying to keep a consistent look."

"Each state varies their process," she said. "They can go all the way from a public competition; they can use school children. Because of that, there [would be] no control over how many initials would ultimately have to go on the coin. [What if a student essay] was the idea? Then do you put the [essayist's] initials on there?"

|

Again, Eskridge said, crediting just the Mint sculptor "has to do with the consistency of the program. Plus, the engraver is the one that did the final sculpt. It's not like the engraver can trace a design. They have to take a drawing and sculpt it into the plaster."

It's the same reason she gives for the Mint's decision not to credit Daniel Carr.

In late 1999 the Mint needed to get the 2001 coin designs going. It deviated from its normal state-quarters routine by inviting both its engraving staff and 14 outside artists to submit designs for the five 2001 coins. One outsider was Carr, a 3-D computer modeler or "virtual sculptor" from Colorado who had been one of seven finalists for the "tails" side of the Sacagawea dollar.

Carr got the nod for the New York and Rhode Island quarters. On instructions from the Mint, he modified his initial designs to appease state officials. Gov. George Pataki wanted a line to run across the map of New York to signify the Erie Canal; Carr added the line. Gov. Lincoln Almond wanted a historic ship from Rhode Island instead of Carr's initial generic sailboat; Carr changed the boat.

Carr's exact designs were sculpted and minted. The Mint paid him $2,500 for each. He got the cash, but only the Mint sculptors got the credit.

"The only proof I have that I designed the quarters is a letter from the Mint asking me to redo the Rhode Island quarter with a specific ship on it," Carr said.

It was apparently proof enough for ICG. The grading service encapsulated his New York and Rhode Island coins and paid him "a small royalty for each one I signed," Carr said.

Carr is believed to be the only non-Mint artist paid by the Mint to design a state quarter already in circulation. However, asked whether Carr is the only outside artist paid for any state quarter at all, Eskridge said no. Some states have awarded cash prizes — and beginning with the 2006 quarters (designed during 2005), the Mint is soliciting designs from its Artistic Infusion Program participants, a group of 21 professional and student artists under Mint contract who are paid for accepted design submittals (professionals get $1,000 and students get $500). A Mint sculptor models the winning designs, and like any other coin, they bear only the sculptor's initials.

Using AIP artists for the state quarters is "part of a whole effort for the Mint to reach out and to ease some of the workload, because we have a lot going on right now," Eskridge said.

Part of that increased workload is related to a major programmatic change the Mint made in March 2003. Beginning with the 2005 state quarters (except California, which was already in the works), the Mint would no longer ask states to submit drawings of their coin concepts. Now, states would be asked to express each "concept or theme ... in narrative format" and the Mint would render it into artwork.

Why?

The Mint vehemently denies that it had anything to do with Paul Jackson. Most outside observers believe it had everything to do with Paul Jackson.

Jackson had become a high-profile problem for the Mint well before March 2003. In the beginning, it wasn't about attribution.

Jackson thought his artwork to be sacrosanct when in May 2001 he submitted a watercolor of two figures from the Lewis and Clark Expedition paddling down the Missouri River with St. Louis' Gateway Arch in the background. He blew a gasket when he learned in April 2002 how the Mint changed his Missouri quarter design.

"Not only was I upset at how they'd dumbed down the design, but they'd even misspelled 'bicentennial," Jackson said.

|

Calling it "Quartergate," Jackson took his protest to the Washington Post and National Public Radio and anybody else who would listen. He rolled a 4-foot mock-up of his original design down Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House to the Mint headquarters in Washington.

When the quarter was released, he made 250,000 stickers showing his original design, affixed them to the coins and placed them back in circulation. That stunt won the attention of The Associated Press, which quoted a Mint spokesman as saying the Secret Service might investigate Jackson for defacing the nation's coinage. The current Mint spokesman said Jackson was never under Secret Service investigation.

"I turned myself in to the Secret Service in Washington," Jackson said. "They threw me out of the building, then off their sidewalk."

Jackson said he has stopped applying the stickers. Today he stamps his initials into the coins with a carbide steel bit he got for Christmas. "I basically cancel them," he said.

Jackson, who admits he's "an artist, not a coin designer," said the Mint told him his original design wasn't coinable.

"I've gotten opinions from 30 different private mints that said it could be coined, and one even did," he said.

The National Collectors Mint — a private coiner that ran afoul with New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer when it issued medals using silver recovered from Ground Zero and marketed them as "legally authorized government issue silver dollar(s)" — produced fantasy medals from Jackson's original design. Today, the Mint's Web site warns consumers that the medal, marketed as "the state quarter that the U.S. Government refused to mint," isn't legal tender despite bearing the words "UNITED STATES OF AMERICA" and "QUARTER DOLLAR."

National Collectors Mint produced proof versions of Jackson's original design on a low-speed coining press. The Mint produces 750 regular-circulation strikes per minute on high-speed presses.

"The Mint is responsible not only for coinability but also for historical accuracy," added White, the Mint spokesman.

The Mint's dugout boat was correct and Jackson's canoe wasn't, White said. Also accurate, he said, were the four figures in the boat. Critics say one resembles Napoleon Bonaparte.

"My design is symbolic of the Corps of Discovery ... and is no less historically accurate than theirs," Jackson said. "Their design ... includes Larry, Moe and Curly in a rubber raft, going downhill, upriver."

"If you read the end of the Louis and Clark journals," Jackson said, "you will discover that the Corps of Discovery returned through Missouri in a flotilla of two-man canoes that they built, bought or stole."

As aggravating as Jackson's "Quartergate" affair may have been for the Mint, the ordeal was taxing on him, too, he said.

"It was a difficult time," Jackson said. "I got divorced in the middle of it, somebody vandalized my art installations, the windows of my gallery were bricked, and my dog died."

So ... did the Mint start asking the states for words instead of pictures to rid itself of pesky artists?

"From the beginning of the program, we asked for narratives," said Gentry, the Mint attorney. The original rules called for states to submit written explanations of their concepts "accompanied by supporting material [such as] photographs or sketches." When states started submitting artwork only, Gentry said, the Mint decided to reemphasize the narrative aspect.

If the Mint didn't want actual artwork, Jackson asks, "then why did they provide a circular template? They were asking for designs." The Mint made coin-shaped templates available to the states, with dotted lines showing the design area.

"The states wanted to engage their citizens," said Gentry. "They said it was more interesting for them to submit actual artwork. So we said, well, here's a template."

"That wasn't really the only part of the program we changed," she said. "It's evolving. It's getting better and better."

COINage Contributing Editor David Ganz, a numismatist and attorney who championed the introduction of the 50-state quarter program, said Jackson's "analysis of what happened is certainly worthy of consideration."

But, he mused, "in the scope of things, does it really matter that it's a stylized version of a boat that may or may not be historically correct? Probably not."

Ganz said he has known all recent Mint engravers and "they are talented artists who work for the government. They are not out to hijack the program. They are out to produce a coinable coin, which is different from an artistic coin."

Michael Castle, the Delaware congressman who authored the 50-state quarter legislation, doesn't mind seeing the coins bear the initials of the Mint engravers, whom he holds in high regard. He also knows Eddy Seger, the uncredited Delaware quarter designer.

"He is recognized for it," Castle said. "I'm sure it will be in his obituary, as it will be in mine."

Private-sector profits for ex-Mint sculptors notwithstanding, Miller of Texas was glad to participate.

"It's a huge honor to be involved in something that's in the pockets of [millions] of people [and] that will be around for thousands of years," he said.

Even if Miller's only federal recognition came when Texas Rep. Martin Frost took it upon himself to read a laudatory statement into The Congressional Record, "the way [Jackson] was treated by the governor of Missouri and the way I was treated by the governor of Texas makes a huge difference," Miller said.

Garrett Burke, who didn't get credit from the Mint for the California quarter design, isn't complaining.

"The U.S. Mint made it very clear that the sculptor's initials go on the coin," he said. "I never had any expectation [otherwise]. You have to leave your ego out of it."

©2005 MILLER MAGAZINES INC./LEON WORDEN. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.