|

|

St. Francis Dam: Too Big Not to Fail

By Alan Pollack, M.D. | Heritage Junction Dispatch, March-April 2010

[PART 1: RISE & FALL OF WILLIAM MULHOLLAND] [PART 2: VICTIMS AND HEROES] [PART 3: TOO BIG NOT TO FAIL]

Just before midnight on the evening of March 12, 1928, William Mulholland's majestic St. Francis Dam suffered a massive collapse, causing a wall of water to travel some 55 miles to the Pacific Ocean and killing up to 600 people in the second-worst disaster in California history after the San Francisco earthquake and fire 22 years earlier.

But why did the St. Francis Dam fail? The headline in the Los Angeles Times of March 17, 1928, declared: "FOUR INQUIRIES UNDER WAY IN VALLEY DAM DISASTER." In the immediate aftermath of the dam break, up to eight agencies began inquiries into the cause of the disaster, including federal, state, county and city governments. The most significant was the 2-week coroner's inquest led by ambitious Los Angeles District Attorney Asa Keyes.

Initial theories abounded as to potential causes, including earthquake, dynamite blasts by road workers, sabotage by the angry residents of the Owens Valley — who felt their water had been stolen by the City of Los Angeles with the completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913 — and inappropriate mixtures of sand and gravel aggregates with the cement used for the dam. District Attorney Keyes was intent on pinning the blame for the disaster on Mulholland.

Keyes and the coroner's jury relentlessly questioned Mulholland about the composition of the concrete, the selection of the dam site on an earthquake fault, the construction and drainage of the foundation of the dam, the anchoring of the dam to the walls of the canyon, and Mulholland's unquestioned role in supervising the dam construction. He accused Mulholland of ignoring leaks in the dam in the days prior to the dam failure.

When asked by Keyes if he would build the dam on the same spot again, Mulholland replied, "No, I must be frank and say that now I would not." Keyes pressed on, asking Mulholland why not. The reply: "It failed, that's why. There is a hoodoo on it. ... It is vulnerable against human aggression, and I would not build it there." Mulholland himself suspected the dam had been dynamited by an Owens Valley conspiracy ring to avenge the building of the aqueduct.

Toward the end of his testimony, Mulholland humbly stated, "Don't blame anybody else, you just fasten it on me. If there is an error of human judgment, I was the human."

The Coroner's Inquest

At the conclusion of the inquest, the coroner's jury stated: "The destruction of this dam was caused by the failure of the rock formations upon which it was built, and not by any error in the design of the dam itself or defect in the materials on which the dam was constructed."

Although jurors expressed ambivalence about the inciting event leading to the collapse, they felt the preponderance of evidence favored an initial failure on the western abutment of the dam, which was anchored to a rock called red Sespe conglomerate. During the inquest, Keyes demonstrated how this rock disintegrates when exposed to water.

Jurors placed the blame squarely on the shoulders of William Mulholland and his Bureau of Water Works and Supply. They further attacked the sole reliance on Mulholland's expertise in building the dam. The final jury statement made national headlines: "The construction of a municipal dam should never be left to the sole judgment of one man, no matter how eminent."

J. David Rogers

Rogers' "Dam Disaster Revisited"Sixty-four years later, Dr. J. David Rogers, Chair of Geological Engineering at the University of Missouri-Rolla, came to a different conclusion about Mulholland's culpability after Rogers used modern techniques to study the failure of the dam.

In papers published in 1992 and 1995, Rogers determined the dam's collapse actually started on the eastern abutment where the dam — unbeknownst to Mulholland and his engineers — was anchored to an ancient Paleolithic landslide made up of a rock called Pelona schist. As the dam was filled up between 1926 and 1928, this unstable hillside became saturated with water, causing a massive landslide on the evening of March 12, 1928. The collapse occurred just five days after the dam was filled for the first time to near capacity on March 7.

Rogers also noted the failure to widen the base of the dam when its height was twice raised by 10 feet (to a total height 205 feet) in order to increase reservoir storage capacity. He showed that due to various deficiencies in the construction of the base of the dam, the structure, during the collapse, actually was lifted by the force of the water and tilted downstream in a phenomenon called "hydraulic uplift."

Rogers noted that the famous center section of the dam, which remained standing, was the only portion of the dam built correctly with 10 uplift relief walls at the base. The landslide caused the entire eastern part of the dam to collapse first, with large blocks of the shattered portion of the dam carried across the downstream face of the main dam. The center section of the dam was then undercut, causing it to tilt and rotate toward the western abutment. This resulted in the collapse of the western portion of the dam as the epic flood waters raced down San Francisquito Canyon wreaking untold havoc and destruction.

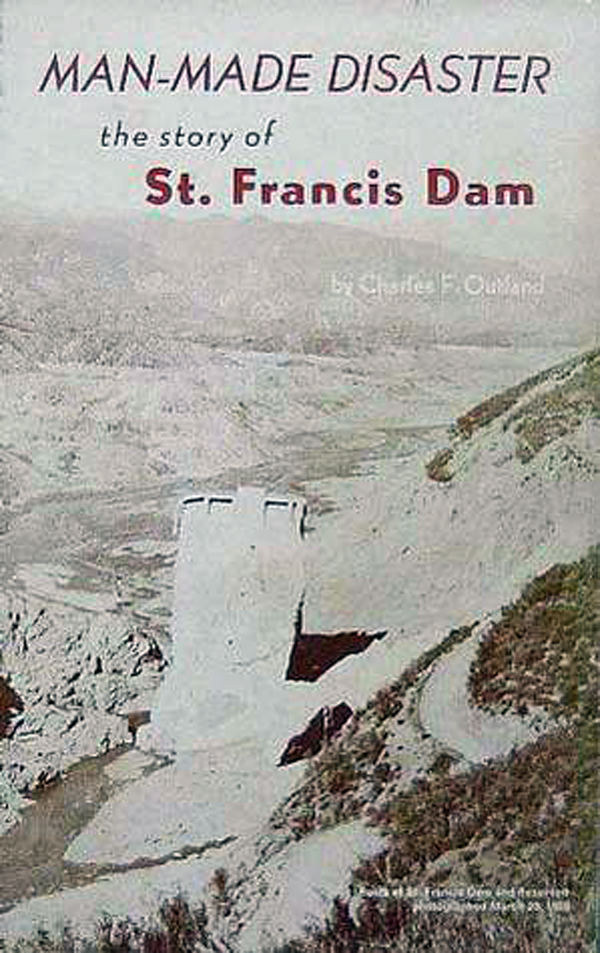

Charles Outland, author, "Man-Made Disaster" Both the coroner's jury in 1928 and Charles Outland in has landmark 1963 book, "Man Made Disaster, The Story of St. Francis Dam," concluded the blame for the disaster primarily rested with William Mulholland. Rogers, while criticizing Mulholland for not using outside consultants and for raising the dam's height in a dangerous fashion, did not find him at personal fault for the failure. Rogers stated: "Mulholland and his Bureau's engineers belonged to a civil engineering community that did not completely appreciate or understand the concepts of effective stress and uplift, precepts just then beginning to gain recognition and acceptance."

To Rogers, the fault lay not with Mulholland but with the lack of knowledge in his profession at the time regarding proper dam construction.

Privilege and Responsibility

Yet the plot thickens. In 2004, Donald C. Jackson, Associate Professor of History at Lafayette College, Easton, Penn., and Norris Hundley Jr., Professor of American History at the University of California, Los Angeles, published an article in the California History journal titled, "Privilege and Responsibility: William Mulholland and the St. Francis Dam Disaster." In the article, the blame shifts back to Mulholland.

Jackson and Hundley point out that while Mulholland correctly placed drainage wells at the base of the center section of the dam, he chose to forgo this and other necessary procedures in the outer parts of the dam, ignoring the possibility of the uplift phenomenon in those sections as water seeped into the adjacent hillsides.

The authors further point out that prior to 1910, little attention was paid to hydraulic uplift in dam building. However, concerns about the phenomenon began to be expressed in the late 1800s and intensified with the collapse of a concrete gravity dam in Austin, Penn., on Sept. 30, 1911, with the loss of at least 78 lives. The collapse of this dam was blamed on hydraulic uplift.

Keeping this tragedy in mind, throughout the 1910s and early 1920s, several concrete curved-gravity dams across the country — all prior to the St. Francis — were built to protect against the uplift problem by using extensive grouting, placement of a drainage system along the length of the dam, and a deep cut-off trench. At least three technical books published in the 1910s pointed out the dangers of uplift and how to compensate for it. Jackson and Hundley further claim: "By 1916-1917, serious concern about uplift on the part of American dam engineers was neither obscure nor unusual. Equally to the point, in the early 1920s, Mulholland's placement of drainage wells only in the center section of St. Francis Dam did not reflect standard practice in California for large concrete gravity dams."

The authors come to the conclusion: "Despite equivocations, denial of dangers that he knew — or reasonably should have known — existed, pretense to scientific knowledge regarding gravity dam technology that he possessed neither through experience nor education, and invocations of 'hoodoos,' William Mulholland understood the great privilege that had been afforded him to build the St. Francis Dam where and how he chose. Because of this privilege — and the decisions that he made — William Mulholland bears responsibility for the St. Francis Dam disaster."

Alan Pollack, M.D., is president of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society.

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.