|

|

Melody Ranch: Movie Magic in Placerita Canyon

By Leon Worden

First Published in The Signal · Saturday, March 29, 2003

Cowboy Poetry Festival-goers who are accustomed to seeing the main street at Melody Ranch in faded brown hues are in for a pleasant surprise this weekend. HBO has repainted the buildings in bright colors to give them that brand-new, 1890s look for its upcoming series, "Deadwood."

Locals came close to seeing a "different" Melody Ranch several years ago when the street was gray-washed for Bruce Willis in "Last Man Standing," but the owners quickly resurrected the normal appearance in time for the crowds.

Color didn't much matter when movie makers were using the Placerita Canyon ranch to feed America's insatiable lust for "B" Westerns in the black-and-white 1930s, '40s and '50s. They'd rename a few buildings and swap out the signs at city limits so that at one moment in 1955 you'd be in "Wichita" with Joel McCrea, and the next you'd be in Dodge City for an episode of "Gunsmoke."

"Put a sign up and that's where you're at," says Renaud Veluzat, who with his brother Andre bought the ranch in 1990 and, since the inception of the city of Santa Clarita's poetry festival in 1994, have opened their doors to the public once a year. The rest of the calendar is consumed with the latest feature film or television series or Pepsi commercial or Jennifer Lopez music video.

But the Melody Ranch story isn't simply a tale of changing a few signs or painting a few buildings. It's a story with roots that run nearly as deep as the origins of cinema in California. It's a story of Hollywood legends cutting their teeth. It's a story of pioneer movie makers — their aspirations and creativity, their rivalries and business deals. And it's a story of a canyon in Newhall that has been seen across the country and around the globe in millions upon millions of feet of film.

Genesis

Newhall grew up with the movies as though it were the most natural small-town thing in the world. Scattered among The Newhall Signal's weekly front-page church notices and amazingly routine automotive fatalities were items such as this, from 1926: "A company of 125 movie folks was here one day this week taking a railroad picture, using the depot as the scene. The cowboy sections of Tom (Mix's) company has also been busy in this section for the past several weeks." Sports reporting amounted to baseball results between the local batsmen and Mix's Wildcats or Harry Carey's Saugus Indians. Society watchers of the '20s and '30s could keep tabs on the area's prominent citizens — businessmen and church elders, but also Carey and William S. Hart and the blackface vaudevillian Charles E. Mack.

Some of the biggest names in "moving pictures" at the time, Hart, Mix and Carey were thoroughly familiar with the canyons around Newhall even in the 1910s, and they would have been aware when some Midwesterners arrived on the scene.

One of those was Trem Carr, a native of Trenton, Ill., who left the construction trade in 1922 when it became clear there was a future in celluloid. By 1926 he was producing films in Placerita Canyon under his own name, Trem Carr Productions Ltd., and he partnered with another Midwesterner who would become a lasting ally — W. Ray Johnston, whose Rayart Pictures Corp. distributed Carr's early films.

Another man who would prove important to Carr was Ernie Hickson, who likewise came out West in 1922 and garnered his first known movie credit in 1924 as a writer. But it was as a set designer and artistic director that Hickson would demonstrate his worth.

Hickson had grown up in Columbus, Ohio, and gravitated toward the stage as a high schooler — initially as an actor but developing an early knack for set design. After school he created sets for a theater troupe that traveled throughout the United States. A historian and collector of old Western memorabilia, Hickson had both the artistry and knowledge to add a good measure of authenticity to Carr's films.

Carr and Johnston cemented their relationship when they formed Syndicate Pictures in 1928. Johnston was president and Carr was vice president, and together they churned out low-budget oaters with Tom Tyler, when they were lucky, in the leading role. Adding to the appeal was the work of J.P. McGowan, and extremely prolific Australian who directed as many as half of the films shot in Placerita Canyon in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

In 1931, Carr and Johnston reorganized Syndicate into Monogram Pictures, with Johnston as president and Carr in charge of production, and Carr took out a five-year lease on land in Placerita Canyon.

They weren't alone in the neighborhood. According to The Newhall Signal of June 4, 1931, "Placerita Canyon has become quite a movie center. At the Jones ranch, a village street has been built for the use of companies making 'Westerns' which are much in vogue right now. The Trem Carr company has also obtained a lease on a ranch, and is planning a 'five year program' ... This is next to the Jones tract."

Hickson built Johnston and Carr their own Western movie street, with aged lumber Hickson picked up in Nevada. The location was just east of the modern junction of Placerita Canyon Road and State Route 14, at today's Golden Oak Ranch — where, in a bizarre twist of history, the Walt Disney Co. would later build a Western movie street. (The same fate awaited the Jones ranch after it became the Andy Jauregui Ranch. Like its next-door neighbor, the Jones/Jauregui property became part of Disney's Golden Oak. But that's another story.)

Everyone was working together in the early '30s. There was Paul Malvern, a young Oregon native who learned the ropes from Carr and soon formed his own company, Lone Star Productions. Carr produced, and Hickson designed sets, for several Lone Star films, which Malvern released through Carr and Johnston's Monogram.

Most of the early Monogram and Lone Star pictures owed their appeal to writer-director Robert N. Bradbury, who frequently cast his son, stage name Bob Steele, in the leading role. Curiously, Bradbury often had Steele's character avenge his father's death.

Steele would become one of the big names in the genre, but he wasn't the only budding luminary to traipse through a Lone Star production in Placerita Canyon. Steele got a job for one of his Glendale High School buddies in his dad's films — a youngster Steele had known as Marion Morrison. Yes, that Marion Morrison — stage name John Wayne — starred in several pictures at the Placerita movie ranch from 1933 to 1935.

Wayne was usually an undercover good guy whom the townsfolk mistook for a bad guy until the end of the 50-plus-minute film. Another local, the talented stuntman Yakima Canutt, was repeatedly cast as the gang leader; George "Gabby" Hayes honed his gruff persona; and Steele's twin brother, Bill Bradbury, occasionally did the off-screen warbling while Wayne — as "Singing Sandy," the original singing movie cowboy — lip-synched to his leading lady or ambled on horseback through Vasquez Rocks.

Growing pains

There was money to be made in this business, but it was a business, with cast and crew and creditors to pay. All of the local upstarts were processing their film at Herbert J. Yates' Consolidated Film Laboratories, and they were getting deeper and deeper into debt to him.

Yates, a Columbia University-educated Midwesterner 10 years their senior, knew that Carr and Johnston and another poverty-row producer named Nat Levine wanted to expand. Yates came up with a plan to square their debts and build an empire. In 1935 Yates masterminded a merger — combining his own Consolidated with Carr and Johnston's Monogram, Malvern's Lone Star, Levine's Mascot Pictures and M.H. Hoffman's Liberty Films — to create a new enterprise called Republic Pictures Corp.

With all of this talent it's little wonder Republic was wildly successful. Then again, with all of these strong personalities, it's a wonder Republic didn't self-destruct. To some extent it did, in the studio offices, anyway.

Yates appointed Johnston as Republic's first president, but there was bad blood between them and Yates quickly replaced him with someone better suited to do his bidding — Levine.

Levine was a high school dropout with gumption. In the 1920s he'd distribute films no one else would touch, and take chances on no-name actors and zany ideas. Singing cowboys like John Wayne — dubbed or not — were adding a new dimension to Western talkies, and Levine was on the lookout in 1934 when he happened upon a promising crooner named Orvon Gene Autry.

Here was an Oakie who couldn't rope or ride, but Levine had Yakima Canutt take care of that with a few lessons. Levine broke Autry in by having him compose a few songs for a pair of Ken Maynard pictures, then vaulted him into the leading role in "The Phantom Empire," a 13-part Western/sci-fi serial set in an underground kingdom, at a rate of $150 a week.

In 1935 Levine, now head of Republic, gave Autry his next lead in a feature — "Tumbling Tumbleweeds," shot primarily on Carr and Johnston's lot in Placerita Canyon. Within three years Autry was a big enough star to renegotiate his contract with Yates, going on strike before Yates relented to Autry's demand for $6,000 for the first two pictures every year and $10,000 for each one thereafter.

Johnston and Carr had broken from Yates by then. According to published interview much later with an elderly Levine, Carr and Johnston walked away voluntarily, while Yates eventually bought out Levine for $1 million — which Levine promptly squandered at the racetrack.

Meanwhile, Carr's five-year lease was up on his Placerita property and he would have to move.

Hickson evidently had amassed a bit of cash, because he was able to purchase some land to the west of Carr's expired leasehold. In 1936 he literally picked up sticks, using a team of horses to skid the Western buildings down the dirt road to the current location at Oak Creek and Placerita Canyon roads.

A lone paragraph in The Newhall Signal of Oct. 15, 1936, doesn't quite tell the whole story: "The Trem Carr Studio is being moved this week to a 10-acre tract of land near the Glen Farnsworth Ranch, about half a mile from its former location. The nearness of oil wells compelled the move."

Monogram again

Hickson's buildings weren't just facades. They were complete structures, with interiors. And more than just a movie set, Hickson erected a self-contained town at the new location, complete with nine permanent residences, corrals for cowboys who stabled their horses there, a restaurant and a bunkhouse for cast and crew who were, in those days, a "fer piece" from Hollywood. Over time Hickson added property to his ranch, which eventually spanned 110 acres.

Free from Yates' leash, Johnston restarted Monogram Productions Inc. in 1937. Carr and Malvern spent the late 1930s producing for Universal, but by 1940 Carr was back at Monogram, relishing the independence it gave him.

Hickson's ranch, as Monogram's "home" studio, was called the Monogram Ranch, and just like today, production companies small and large — Paramount, RKO, Republic — were renting it out for the variety of scenes it offered. Sets, according to a list by resident ranch manager Charles Hays, included the main Western street, a log cabin and pioneer settlement, a Mexican street and hacienda, an Indian compound, a country schoolhouse and playground, a relay post, barns and corrals, and a trading post.

Hickson provided all the power, lights and cable the producers needed and, from his collections, period furniture and fixtures to dress the sets, as well as merchandise to fit out an old-time grocery, drug, hardware or general store.

Hickson reported that 30 films were made at the ranch in 91 working days during 1940, up from 20 films in 1939. Labor in 1940 included 7,000 movie company employees; 14 Newhall residents on Hickson's payroll; 14,400 hours of set preparation at $1.10 an hour; seven restaurant workers; and various maintenance men, maids, cowboys and extras.

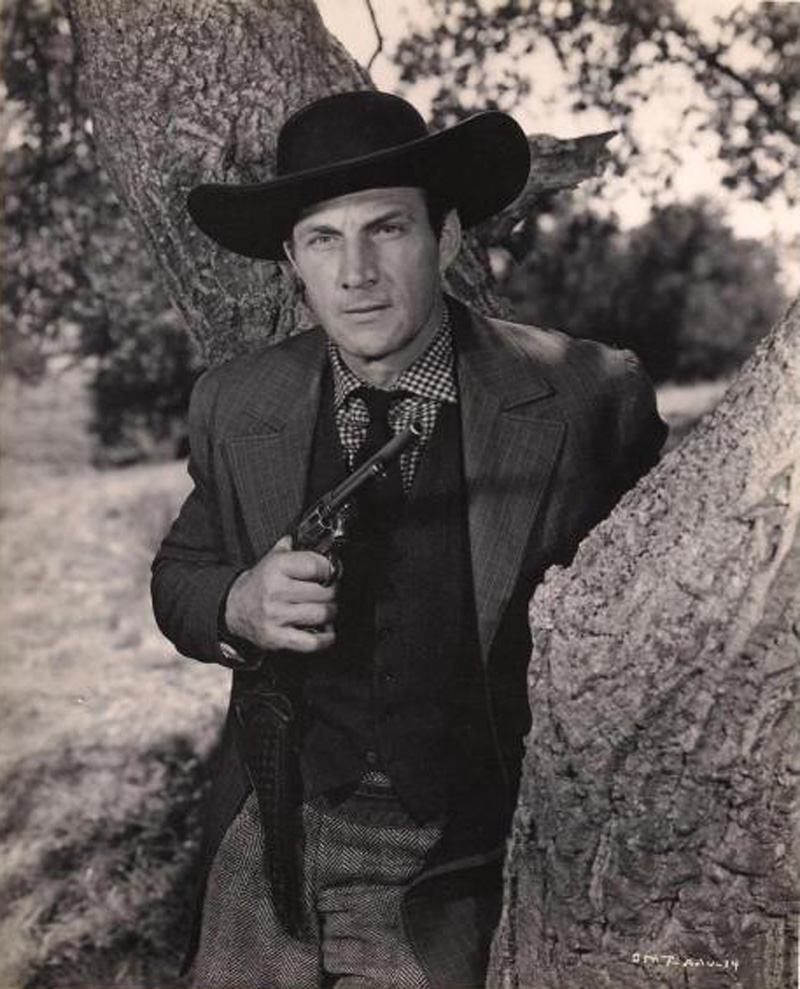

There were also 5,000 sight-seers in 1940. Visitors were permitted on Sundays by request. Among the 7,000 movie company people were William Boyd (as Hopalong Cassidy), crooner Tex Ritter, Ray "Crash" Corrigan and Jack Randall. John Wayne and Claire Trevor reprised their 1939 "Stagecoach" matchup, which wasn't filmed at Monogram, with 1940's "Dark Command," which was. Fourth billing, behind Walter Pidgeon, went to Roy Rogers.

While their paths still crossed more often than not, Hickson and Carr started going their separate ways. Hickson, as the property owner, officially renamed his ranch the "Placeritos" on June 21, 1941, and did so in a big celebration with Newhall residents and Hollywood people that included archery and horseshoe pitching, burro rides for kids and a bucking horse contest.

Carr, now a 50-year-old studio executive, tested the waters in other genres. Monogram signed Boris Karloff to a half-dozen films in 1939 and 1940 — including "The Ape," shot at Hickson's ranch. From 1941-44 a washed-up Bela Lugosi signed on for what cultists call the "Monogram 9," with locations in Placerita Canyon and indoor work in East Hollywood, where Monogram bought and expanded a studio in 1942-43. Charlie Chan and the Bowery Boys were Monogram's, too.

Westerns were still king, and Monogram targeted the Saturday matinee crowd with "trio" series — low-budget films with three recurring stars who were past their prime but could still draw an audience.

In 1941 Carr, actor Charles "Buck" Jones and Monogram production boss Scott R. Dunlap each invested $3,300 to create Monogram's "Rough Riders," featuring Jones, Tim McCoy and Ray Hatton. They made eight pictures before Buck died in the Cocoanut Grove fire. Years later, Dunlap bought out Carr and Buck's interest on the cheap, and pocketed $250,000 when he sold the series to television.

Monogram came back with the multi-hero "Range Busters" series in 1942-43 and in 1943-44 produced eight pictures with Ken Maynard, Hoot Gibson and Bob Steele as the "Trail Blazers."

Perhaps no single actor epitomizes Monogram's output at Hickson's movie ranch during the 1940s quite like Johnny Mack Brown.

A veteran of MGM, Universal and other big houses, Brown was cut in 1943 when Universal decided to polish its image and dump low-budget Westerns. Brown found a home at Monogram, where he churned out more than 60 pictures over the next decade and was one of the top 10 money-makers in the Western film business.

But the sun was setting on "B" Westerns.

Trem Carr died in 1946 and Steve Broidy took over at Monogram. That year Broidy formed Allied Artists as a subsidiary to distribute Monogram's meatier productions. Television was taking a bigger and bigger bite out of the Saturday matinee. Broidy shut down the low-budget side in 1952 and put Johnny Mack Brown to pasture. In 1953 he erased the Monogram name altogether in favor of Allied Artists, and in 1964 Allied moved to New York.

Television

Rather than die with the "B" Western, Hickson's Placeritos Ranch made the transition to the small screen. But Ernie Hickson, himself, didn't.

Gene Autry had been interested in Hickson's movie town ever since he first laid eyes on it in "Tumbling Tumbleweeds." By now a millionaire star of film and radio with a traveling road show, rodeo, and top-10 recordings that ran the gamut from "Mexicali Rose" to "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer," Autry was in a position to buy the Placeritos from Hickson's widow, Bess, following Hickson's death on Jan. 22, 1952.

The sale was reported in The Newhall Signal a year later, on Jan. 22, 1953, which acknowledged that Autry "will continue the ranch as a movie-making location" but heralded the news as "the end of an era for some folks."

"(The ranch) has come to be an institution in this area and was the site of the colorful Old West (July 4) Celebrations in 1949, '50 and '51," Signal Publisher Fred W. Trueblood writes. "The most outstanding feature of the ranch was the remarkable old museum that Mr. Hickson had collected over the years. ... One of the most interesting items perhaps was a number of very old-fashioned slot machines that were found in the old west saloon. These old-time, one-armed bandits not only snatched your quarter but gave you a colorful spinning of assorted wheels and played a tune to boot."

The ranch known as the Placeritos, nicknamed "Slippery Gulch" when it hosted Newhall's July 4th festivities, was now called Melody Ranch — a name Autry had coined in song and celluloid more than a decade earlier.

Trueblood was correct in predicting that the ranch wouldn't be quite as "public" as it had been under Hickson's ownership, but there was no slowdown in production.

Autry leased the ranch to feature film producers — Allied, Columbia and United Artists were big users — but it was most often seen in living rooms from coast to coast when "The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp" with Hugh O'Brian went into production in 1955. CBS countered the same year with a Western series of its own at Melody Ranch — "Gunsmoke," starring James Arness and Amanda Blake.

Autry's own production company, Flying A Pictures, used Melody Ranch for some of its own productions in the mid-1950s — not "The Gene Autry Show," but rather "Annie Oakley" with Gail Davis and "Buffalo Bill Jr." with Dickie Jones.

Autry himself went before the cameras at Melody Ranch for the last time in 1958 when he appeared alongside John Wayne in a network retrospective on Western movies. In 1961 Autry quit his road shows and bought the California Angels baseball team.

Then came Aug. 28, 1962.

The first blaze broke out just after noon in Hasley Canyon, north of Castaic Junction. The second broke out an hour later on a ranch between Newhall and Saugus. High winds whipped the flames into the most intense inferno anyone had ever seen.

When the smoke cleared three days later 17,200 acres had been scorched and 15 structures and numerous out-buildings were lost. No one was killed, but the Western street at Melody Ranch, the setting for "High Noon's" immortal face-down, was gone.

"I had always planned to erect a Western museum there," Autry remembered in 1995, "but priceless Indian relics and a collection of rare guns, including a set used by Billy the Kid, went up in smoke. Thank God, the ranch hands and all 14 of our horses were uninjured."

Of course, Autry did go on to build a museum, but not in Placerita Canyon. The Gene Autry Museum of Western Heritage opened in 1988 in Griffith Park.

The fire spared little. Elvis Presley was on location for a (still) photo shoot when the flames swept through, and he helped save one of the structures by dousing it with buckets of water when it caught fire. The house, still there, had reportedly been used in the 1940 picture "My Little Chickadee" with Mae West and W.C. Fields.

Also spared were two turn-of-the-century locomotives that Autry purchased as derelicts in the mid-1950s for use as props in series like "The Virginian." In 1972 Autry gave one of the train engines back to he Denver & Rio Grande Railroad for use on a tourist line, and the other he donated in 1982 to the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. It's parked in front of the Saugus Train Station in downtown Newhall today.

Production didn't grind to a halt altogether. "The terrain (was) so battle-scarred," Autry said, "that it was used two months later for an episode of television's war series, 'Combat.'"

But primarily Melody Ranch was where Autry pastured his famous movie horse, Champion.

Autry's first wife, Ina, handled the business affairs, and after the fire she hired one of his road-show performers, Henry Crowell, to run the ranch. Autry would visit only a few more times.

"I cared for Champion and the other horses at Melody Ranch and managed the ranch for over 30 years," Crowell recalled in 1997. "One of the hardest things I ever had to do was to put Champion to sleep.

"The date was May 9, 1990. I'll never forget it. Champ was a lot more than just a horse. Champion was my special friend. I could make Champ smile just by raising one hand."

Ina Autry died in 1980. In 1981 Gene married Jackie Ellam, who sold off the 110-acre ranch piece by piece, and who is ungraciously remembered by locals as the reason Autry's museum ended up in Los Angeles instead of Newhall.

"I kept (Melody Ranch) until the last living Champion died," Autry remembered.

With Champion's death, the final remaining 10 acres, where Ernie Hickson had moved his Western movie street in 1936, went on the market.

Today

Paul T. Veluzat arrived in 1939 and bought a ranch in the Haskell Canyon area of Saugus. Like many ranchers of the period, he leased it out for location filming. Veluzat's three sons, Rene, Renaud and Andre, all found their way into the movie business, initially by renting jeeps and tanks to film makers.

Andre and Renaud still run their motion picture vehicle rental business in Newhall, as well as their late father's movie ranch in Saugus. In December 1990 they jumped at the chance to buy the historic Melody Ranch property and rebuild the Western street.

Andre and Renaud had no blueprints to work from when they started work in 1991. But Autry had thousands of fans, and many had old photographs of themselves in front of the buildings. Old films helped, too.

"We knew how tall John Wayne was," says Andre, "so we'd scale that wood according to his height."

Keen on accuracy, they'd analyze the images of Wayne to determine whether a particular building called for 1-by-6's or 1-by-8's.

Autry would pay an infrequent visit to check on their progress, and within 15 months they were ready to go.

Today the Melody Ranch Motion Picture Studio is a 22-acre complex — the Veluzats acquired a second parcel — with two large sound stages, more than 65 storefronts, and several complete interiors including hotels, a bank, a church and a jail. Construction continues on a remake of the hacienda Hickson built in the 1930s, with antique doors the Veluzats found in a Warner Bros. warehouse. Future plans call for the reconstruction of the Mexican street, and like Hickson, they have a prop house for dressing sets in authentic, old-West style.

Already they've built the museum Newhall residents had hoped for. Open by appointment, it houses a beautiful collection of 1930s cars the Veluzat brothers amassed over the years as well as the tank Renaud drove in "Rambo III," a stagecoach from the "Maverick" remake, one of the "General Lee" cars that the brothers provided for "The Dukes of Hazzard," lobby cards from old films shot at the ranch, and more.

One thing that has changed since the old days is the amount of use Melody Ranch sees. It's rented to producers all year 'round except for one weekend, when the Veluzats host the city's annual Cowboy Poetry and Music Festival. It's something they've done ever since the first festival 10 years ago, when the earthquake of Jan. 17, 1994, scuttled the city's plans to hold it in the Hart High School auditorium.

"The Veluzat family so graciously and wonderfully said, 'How would you like to do this at Melody Ranch?'" said modern-day Western singer Don Edwards. "What better place to do a festival than Melody Ranch?"

Indeed.

For more photos of Melody Ranch, and an original story by Gene Autry, click here.

Click here for an older, shorter version of this story.

©2003 LEON WORDEN

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.