|

|

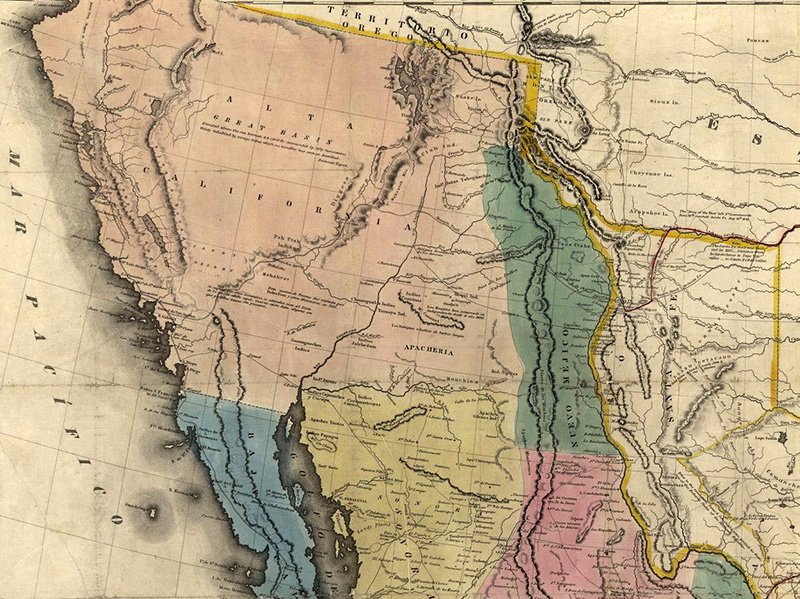

2. Rancho San FranciscoRancho San Francisco might be said to date from the founding of Mission San Fernando In 1797. It commences at the intersection of Piru Creek and the Little Santa Clara River, thence easterly, including all of the valley flat lands, to a point known then as "la Soledad," now better known as Solemint on Highway 6[3]. As originally claimed by the Mission, it included over 102,000 acres, and was the northerly rancho — Camulos was then an integral part of Rancho San Francisco — and probably, the limit of influence of the Mission San Fernando. That is logical, for it has already been pointed out that between the Piru Creek and the Sespe was a definite line of demarcation of the cultures, whilst from Piru Creek to Newhall the same language and customs prevailed.

In the original setup of the Mission chain, developed after the exploratory work of the Sacred Expedition in 1769, three Missions were tentatively projected for the Little Santa Clara Valley. They were Santa Barbara, San Buenaventura, and Santa Clara. Santa Clara was to have been located at Kash Tuk, or Chaguayabit, known today as the land back of Castaic Junction[4], and referred to by Fr. Crespi as the Rancheria del Corral.

Quoting from the correspondence of Fr. Palou:

Besides this Mission (San Buenaventura), orders have been given to found another named Santa Clara in the country between San Gabriel and San Buenaventura, and an eye has been cast on the valley of that saint, at the head of it, where, they say, are good land and water and everything else desirable for the founding of Missions.

This site is about seven leagues from that of San Gabriel and 14 from the site destined for that of San Buenaventura. The site designed for Santa Clara is somewhat apart from the Camino Real now in use, and it has not been seen since the expedition passed there, hence it is necessary to go there to examine it, which has not been done on account of the lack of soldiers already mentioned.

Camino Real Moved

The precipitous crest of the San Fernando Pass had caused the moving of the Camino Real, or the original route of Portola, over to the Santa Susanna Pass, comparatively easy to negotiate. Chaguayabit, or Castaic Junction, was altogether too much of a back haul, as it were, under the improved road setup. It was also true that a site upon the mesa would have been considerably higher than the creek bed. It was before the days of booster pumps. Santa Clara Mission at the Castaic Junction was never built.

There was a jump of 75 miles between San Gabriel Mission and San Buenaventura Mission, almost a three-day march. The Encino (San Fernando) Valley also was the site of a very large number of Indian rancherias, or villages, too isolated from the missions for either active conversions or later administration.

Fr. Serra died at San Carlos Mission in 1784. His associate, Fr. Lasuen, succeeded him as Presidente of the California Missions, and, as fast as California politics, interpreted by the California civil governor, would permit, undertook the work of filling in the gaps in the chain of Missions.

Explorers Report

In 1795, an expedition to which was attached Fr. Vincente de Santa Maria, explored the valley north of San Gabriel for a Mission site. His report, quoted from Fr. Engelhardt's "San Fernando Rey," and sent from Mission San Buenaventura on Sept. 3, 1795, reads:

My Most Venerable and Esteemed Fr. Presidente:

In compliance with the resolution of the Governor that an examination be made with the greatest exactitude and in a thoroughly satisfactory manner, in order to find the best place between this Mission and that of San Gabriel so that we may proceed with assurance in case the founding of another Mission between this and that be conceded; and since His Honor wishes that a Missionary make the survey, and your Reverence has trusted this charge to me, I shall have to execute it perfectly.

I have to report that on August 16th, at 12 o'clock, at noon, I set out from this Mission accompanied by Ensign Don Pablo Cota, Sergeant Don Jose Maria Ortega, and four soldiers.

On the nineteenth we left Calabazas at half past six in the morning, going on the Camino Real as far as the Encino Valley, from where we took the direction towards the east northwest. We went to explore the place where the Alcalde of the Pueblo (Los Angeles), Francisco Reyes, has his rancho. It lies in front of Encino, facing the north, and it is distant from the Camino Real about two leagues.

We found the place quite suitable for a Mission, because it has much water, much humid land, and also limestone. Stone for the foundations of buildings is nearby. There is pine timber in the direction of west-northwest of said locality, not very far away; also pastures are to be found and patches very suitable for cattle; but there is lack of firewood. To this locality belong, and they acknowledge it, the gentiles of other rancherias who have not affiliated with Mission San Gabriel.

On the twenty-fifth, we set out. After a league and a half we found ourselves at a Pass which was very rough, so that, in order to ascend and descend it, we had to alight. At a little distance from the descent we encountered a little ditch of water where we stopped at six in the evening.

On the twenty-sixth we set out from there at six in the morning and at eight we reached said place and came to a rancheria contiguous to a zanja of very copious water. We followed this ditch to its beginning, which was about a league distant; and from here it is where the Rio de Santa Clara takes origin.

This zanja is very easy of access, so that with its water some land can be irrigated, but in said district we found no place suitable for establishing a Mission. It is six leagues distant from the Camino Real to the north and it has the additional drawback of the Pass thru the Sierra.

The first description is, of course, the present site of Mission San Fernando, the second description is of the Little Santa Clara Valley headwater, which then, if ever, needed just one good modern Realtor to talk his way past the roughness of the mountain road and assure the good Padre of many wide boulevards in the future. As might be expected, without that aid, the San Fernando Valley, yet to be, won its first competitive struggle with the headwaters area of the Little Santa Clara.

The Mission Influence

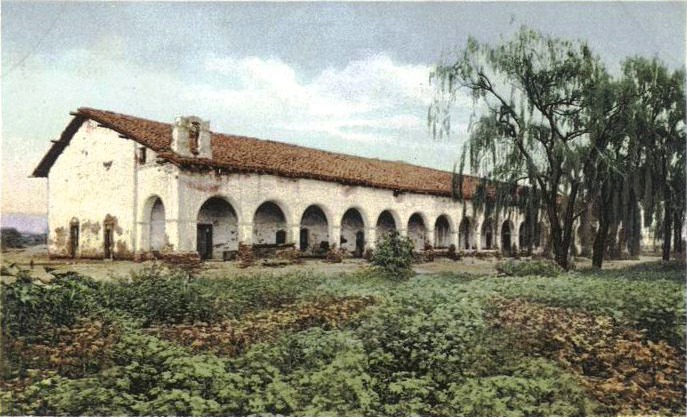

San Fernando Mission was built in 1797.

The mountain range and Pass to which Fr. Santa Maria objected remained in place with one major result: The large gentile (unconverted) Indian population above Chaguayabit was for practical purposes still beyond the influence of Mission San Fernando, and was still 40 miles distant from Mission San Buenaventura, another land whose people spoke another tongue.

Under the Spanish colonization system, the Missions practically supported the Presidios, where the military was maintained. Santa Barbara Presidio, for example, depended in part upon the contributions of grain, hides, soap tallow, etc., from Mission San Fernando — after it got going.

It was more than a day's trip from Mission San Fernando to Mission San Buenaventura. It has been mentioned that Rancho San Francisco and its included Camulos (Kamulus, if you prefer) rancho were part of Mission San Fernando's sphere of influence.

They were also on the Ventura/Santa Barbara side of the San Fernando mountains and had good, arable land which could produce sufficiently to meet the Presidio requisitions. In 1804, one Francisco Avila had attempted to denounce part of the holding on the ground of disuse.

The Fathers had successfully fought off that attempt, but things added up that an Asistencia on Rancho San Francisco could be of great aid to Mission San Fernando.

Asistencia Constructed

So it was that Fr. Dumetz built the Asistencia, the first building in our valley area.

Webmaster's note: As of 2006, modern archaeologists do not believe the estancia (mission outpost) at Castaic Junction was elevated to asistencia (sub-mission) status.

Fr. Engelhardt, in "San Fernando Rey," says: "At Rancho de San Francisco Javier, or Chaguayabit, a building was erected 38-by-6 varas (about 105 feet by 17 feet) in size. It was divided so as to provide for a granary and other necessary rooms." It was built in 1804.

For years the search went on for that building. It was too big to be completely lost. A note from Fr. Engelhardt in 1929 stated that Franciscan records had no details as to Asistencia locations. In 1935, R.F. Van Valkenburgh and the writer were screening for a stone dam, known to have been erected by San Fernando Mission a century back. It was never found, but, naturally, that search ended in the Asistencia ruins.

The archeologic "dig" was under Arthur Woodward, then curator of history at the Los Angeles County Museum. The parties were various, including Dr. John E. Nordskog, then on the faculty at University of Southern California; Rev. George Hill, of Pasadena, then a college student; the entire Perkins family, without any exceptions. The pictures taken by various party members were of course mislaid.

The "dig" indicated five rooms in the long structure, the living quarters having a tile floor and an altar in the main room, and whitewashed walls. The roof was tile, typical Mission.

The eastern end of the building was evidently the granary. There was a dormitory for night stacking of the Neophytes.

Sixty feet southerly from the structure, there was another long building, apparently storerooms and trade rooms, running to the kiln where the tile had been baked.

Asistencia Destroyed

Dreams of a reconstruction, similar to that of the Asistencia at Riverside, vanished when in 1936 vandals dug the tile floor out and undermined the walls in a futile effort to find the "Mission Treasure" the archaeologists had located under the floor — for when the diggers stopped the days' excavating, dirt was always spread over the tiles in the faint hope that unnoticed they would not be swiped.

San Fernando Mission was secularized in 1834. The gold discoveries were made in 1842.

The Asistencia stood upon lands of The Newhall Land & Farming Company. In June, 1946, a party escorted to the site was somewhat dismayed to find that the mesa had not only been plowed up, but apparently bulldozed, the only known treatment that will totally eliminate wall traces in ground.

At one time, the part had some four feet of standing wall; tile or plastered floors throughout the main building; the kiln excavated and the ramada traced and any amount of unbroken roof and floor tile.

The Asistencia work was done when Mr. Chesebrough was in charge of the ranch. The Newhall Land & Farming Co., through him, was quite cooperative. After Mr. Chesebrough left, his successor may have known nothing about the dig.

It would still be a nice idea to have a Historic Site plaque set down on the road to Ventura[5].

The Asistencia was also the first hacienda of the Del Valles, when the grant was made to them of the ranch.

Geographically, Rancho San Francisco is headwater area of the Little Santa Clara River. Chronologically, it may be said to begin in 1797, at the time of founding of Mission San Fernando, and ending in 1876 when Henry M. Newhall deeded the 426-acre townsite to the Western Improvement Company, a real estate subsidiary of the Southern Pacific Railroad. Until that date, the Rancho dominated the valley, first from the Asistencia as such, then from the Ranch Hacienda of the Del Valle family at Camulos. After 1876, the town of Newhall starts to develop, and the Rancho is known only as the "Newhall Ranch."

Primitive in 1804

To 1804, the valley was completely primitive. An occasional Spaniard may have come through at long intervals, but the Camino was far away and the Missions too far distant to be a serious menace to traditional life and customs. There may have been about 1,500 in the local Indian population, scattered among some 20-odd rancherias.

Henceforth, everything is different. The Asistencia became, to the Indians, a workshop. The tribal associations of the villages gradually gave way to Mission affiliation.

The medicine men could not compete with the grey-frocked friars. Finally, the older men of the tribe sorrowfully bundled up their ceremonial regalia in five-foot woven storage baskets; headresses, cordons and sashes of featherwork, the regalia that had been used to propitiate the Gods for centuries — all went into the storage baskets and they were carried to a cave high in the precipitous cliffs of San Martinez Chiquito, in plain view of the Asistencia, and left.

Cave Cache Discovered

In 1884, the Pyle boys, hunting on their Mud Springs ranch, got into the cave. They sold the cave's contents to Stephen Bowers (which is why the cave is known as Bowers Cave) for $15 F.O.B. Ventura, where Bowers was then editing a newspaper. Bowers sold the whole thing to the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., where, according to recent correspondence, it is today[6].

Dr. John P. Harrington and R.F. Van Valkenburgh located the cave in 1933. It was dug out. The five-note flute made from the thigh bone of the deer, a soapstone pipe, a deer horn flaker, several awls, manos, an arrow straightener, asphalt chunks, a basket hopper base, and pieces of basketry were all that was recovered. On the ceiling of the cave, in smoke print is inscribed: "Mac Pyle 1884."

Lo, The Poor Indians

Indians are not illogical. How they reconciled the teachings of the Franciscans with the actions of the Spanish soldiers, the only other white people with whom they had had contact, is difficult to conceive.

And further, the Padres kept saying the lands belonged to the Indians, and that the Padres were only Trustees; but the Indians did the work without recompense to either labor or owner — if they were owners.

With the Mission Asistencia practically sitting on top of the local Indian villages, Mission influence spread rapidly. In some places it appears to have been quite simple. First, the Padres grabbed and baptized the baby. Then it was theirs. Quite naturally, the mother came after the baby. If the father wanted the family, he could come too.

Land had to be cleared, livestock had to be tended. The Presidio economic overlordship made requisite cobblers, tailors, muleteers and sempstresses, blacksmiths.

Labor was necessary to till fields, prepare the quantities of food necessary to feed the neophytes living at the Mission under direct control of the Fathers or their designated Indian foremen.

To build of adobe, brick had to be made; crushed shell which abounds in the local ranges had to be brought in. Its use made the lower tiers of the adobe bricks impervious to water. Tiles for roof and floor use had to be burned. Carpentry had to be undertaken. Young neophytes even received an elemental musical instruction to enable them to sing responses at Mass.

Discipline and Disease

Traditional tribal customs were forced to give way to the Mission system. From Candelaria and other contemporary witnesses it is gathered that whipping stocks and starving were the usual method of enforcing the new disciplines.

Personal rights of the native Indians were nonexistent.

The Spaniards brought with them disease and drink. The Temescal, always the first line of defense against Indian ills, was suicidal against imported diseases. The imported fevers of the Spaniard flamed but the higher in the sweat baths.

What became of the Indians? There are practically none left. There were supposed to have been over 100,000 of them in 1823. The black small pox epidemic of the (1860s) may have finished the processes started at the turn of the century. The late Charles Moore, who survived the disease in the epidemic, has told of the pit burials of the San Fernando Mission Indians. There were too many corpses for individual interments.

Government Exactions

It would be grossly unfair to leave the reader with the impression that all Missions treated the Indians cruelly or unfairly.

That probably was not the case. The Mission Fathers had their own problems, not the least of which stemmed from the requisitions of the Presidios. Again quoting from Fr. Engelhardt — Sept. 17, 1821, Fr. Ybarra writes from Mission San Fernando to el Commandante De la Guerra at Santa Barbara Presidio as follows:

"I just came from the Rancho de San Francisco. Things are as I said. There are only sixty to seventy fanegas. Rabbits and hares, and worms have done damage to the crop. In effect, on Monday I shall order 29 fanegas to be husked which will be taken as far as Santa Buena Ventura." This answering a requisition for 80 fanegas.

June 29, 1825, Fr. Ybarra again writes to De la Guerra: "By Saturday there will be at San Buena Ventura fifty fanegas of corn. There are no beans." Again, August 9, Fr. Ybarra writes: "Yesterday the 8th, I received your official note asking for $300 worth of soap. To this, I must say that there are thirty of forty dollars worth of that article for none has been made this year, and very little last. There are on hand one hundred fanegas of beans. Of this quantity twenty-five to thirty are necessary for the guards, ten must be deducted for the tithe, sixteen are to be forwarded to the Presidio of Santa Barbara. That leaves forty-four, or forty-nine for the Indian creditors, the real owners, those who picked them first on account of the labor and care, and then on account of the punishments subjected to."

Mexican Attitudes

It should be pointed out that the dating of the quoted letters shows them to reflect the Mexican regime, Spain having been expelled from Mexico in 1821. The native Mexicans were under no illusions as to Missions and Mission influence. Mexico itself had seen too much of that in the past. There was no longer a King of Spain to whom the Padres could complain, going over the heads of the Mexican authorities. In short, the background had changed and the trend was toward the possible slogan of "Mexico for the Mexicans."

The relations of the Missions to the Civil Government is aptly expressed in a further quote from Fr. Ybarra, who, on April 11, 1825, writes Carlos Carrillo:

That one should serve and respect him who is of benefit, is very proper and just; but that one should feed him who not only does not protect but positively destroys, requires a stout heart. In effect, what benefit do I receive or have I and the Mission received from your Presidio? None. What damages, on the other hand? Incalculable. Yes, yes, if the Presidio did not exist, I could figure on my labor and toil. In that case, I should mind neither the Tulares nor the Sierras, the refuge of wicked men. The second Sierra, or bawdry (Alcabueteria), your Presidio, it is that annoys me. If a low man should behave in a low manner, one should not be surprised: but that men who regard themselves as honorable should act thus, this is what stuns.

In this letter he also intimates that the soldiers ought to work and raise grain and not live by the toil of neophytes whom they rob and deceive by their talk of liberty. "The liberty which you hold up to these unfortunates is nothing more than slavery, which contents only a few fools."

The reader certainly knows by now what the Missions think of the Civil Government, and it is reasonably obvious what the Presidios think of the Missions — a cheap source of supplies.

Well, what did the Indian think?

Indians Apathetic

In 1813 an "Interrogatorio" to Mission San Fernando answered that question, in the words of Fr. Munoz: "At present there is not observed any aversion for either Europeans or Americans, rather only a supreme indifference" (by the Indian).

Trends are like unto the tides. They cannot be swept away but they themselves will sweep where they will.

In 1769, there were tremendous unused lands to be had for the taking, for no one wanted them. The Mission policy was always to claim all the flat and valley lands, all of the way to the lands claimed by the next Mission.

In 1830, glance at the results of that policy. Mission San Fernando was laying claim to Rancho San Francisco, then including over 102,000 acres; to Rancho Simi, with 113,000 acres; Rancho San Fernando, about 138,000 acres. There may have been some other ranchos involved, but those cited total over 353,000 acres.

Fr. Engelhardt states that 1811 was the Missions' zenith with 1,081 converts. In 1832, the same source gives 782 as the Mission population (if you want to call it that).

Cattle Predominant

At that time, almost the only thing California land could be profitably utilized for was cattle. Lots of this land is of such quality that 50 to 100 acres per head would not be too fantastic. Outside of the small amount used for food, the marketable product per cow was only the hide and tallow. A couple of times a year, a trader ship would sail up the coastline, trading out stored supplies of the rancheros. Outside of the goods brought in by these ships, there was nothing to be bought of goods or supplies.

Bryant & Sturgis, of Boston, seem to have been the most consistent Coastal traders.

In the time that had elapsed, two generations of true Californians had developed. With Mission San Fernando as a criterion, secularization of the Missions was inevitable.

Del Valles Take Over

A Mission with fewer than 800 Indian converts was tying up 353,000 acres of land. The Mexican Government was cognizant of the condition and as early as 1824 was planning secularization. When it came, Mission San Fernando was the first to fall; in 1834 Rancho San Francisco passed into the hands of the Del Valles, who utilized the estancia as their home, and put cattle on the broad valley fields.

In 1834, Mission San Fernando was secularized by Lieutenant Antonio del Valle by order of the Governor, Jose Figueroa[7]. From study of the records, it is difficult to understand the exact current status of Rancho San Francisco.

By one reading, it is possible to assume that as early as 1824, all, or part, possibly the Camulos portion, may have been utilized by Antonio del Valle for grazing his stock under some sort of grant or permission from authority. On the other hand, the return of William Hartnell, auditing, as it were, the condition of Missions in 1835, might indicate that as of that date, Rancho San Francisco became private property of Del Valle.

By color of title or without title from that time on, Del Valle remained in possession of the Rancho. For a couple of years he had some trouble caused by Indians raiding his stock. They apparently claimed they were only reclaiming their own property and at least once, the old estancia, as a hacienda, was utilized as a fort for defense of person and property. By 1840, Del Valle's family was able to live on the ranch safely.

Del Valle married Jacopa Feliz, a Lopez family lady, much younger than the husband. Francisco Lopez was a relation of hers, and may have been ranch manager for Del Valle[8].

©1954, SANTA CLARITA VALLEY HISTORICAL SOCIETY • RIGHTS RESERVED.

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.