|

|

Sellout Crowd Revisits 1928 Tragedy

By Dianne Erskine-Hellrigel

SCVHistory.com | March 12, 2016.

|

Local historian Philip Scorza opened the festivities by showing a film he created with fascinating old footage and historical photos from the early 1900s. Phil was followed by an engaging and in-depth historical account of the quest for water in Los Angeles, the key characters involved in obtaining that water, the water wars that followed, and the eventual arrival of precious water in Los Angeles. This portion of the program was narrated by the brilliant Dr. Alan Pollack, president of the Historical Society. I spoke about the nearly forgotten personal stories - the people who lived, the people who died, the hopes and dreams that were lost in a wall of water that ravaged the Santa Clara River Valley. The date was March 12, 1928.

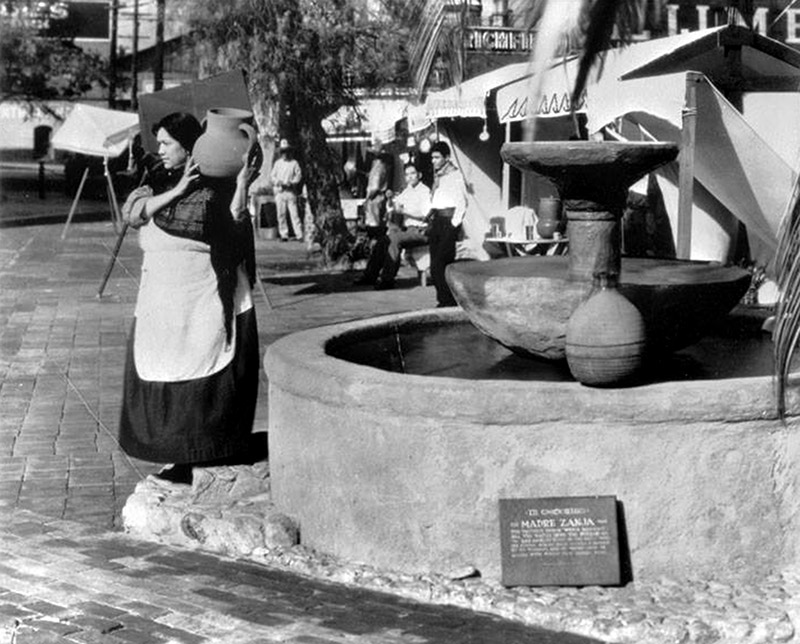

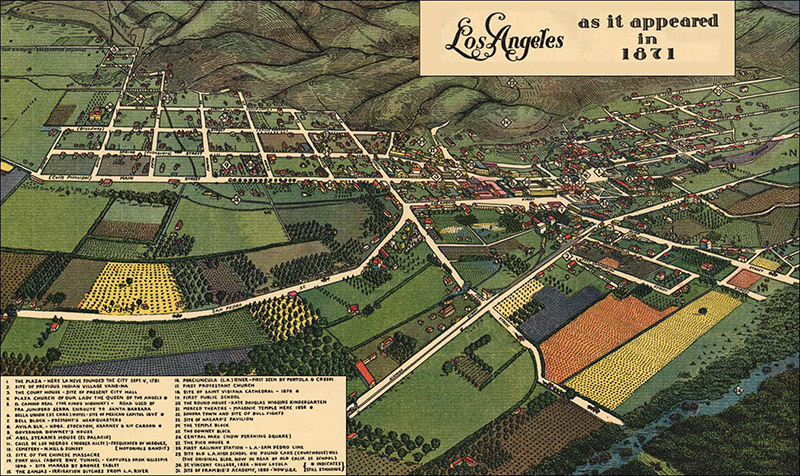

In the earliest days in Los Angeles, the Los Angeles River was enough to sustain the small pueblo of inhabitants. Water was carried from the river to the population of the region by ditches called zanjas. A man named Fred Eaton became the superintendent of the Los Angeles City Water Co. He would become one of the principal figures involved in bringing water to Los Angeles, along with an Irish immigrant named William Mulholland.

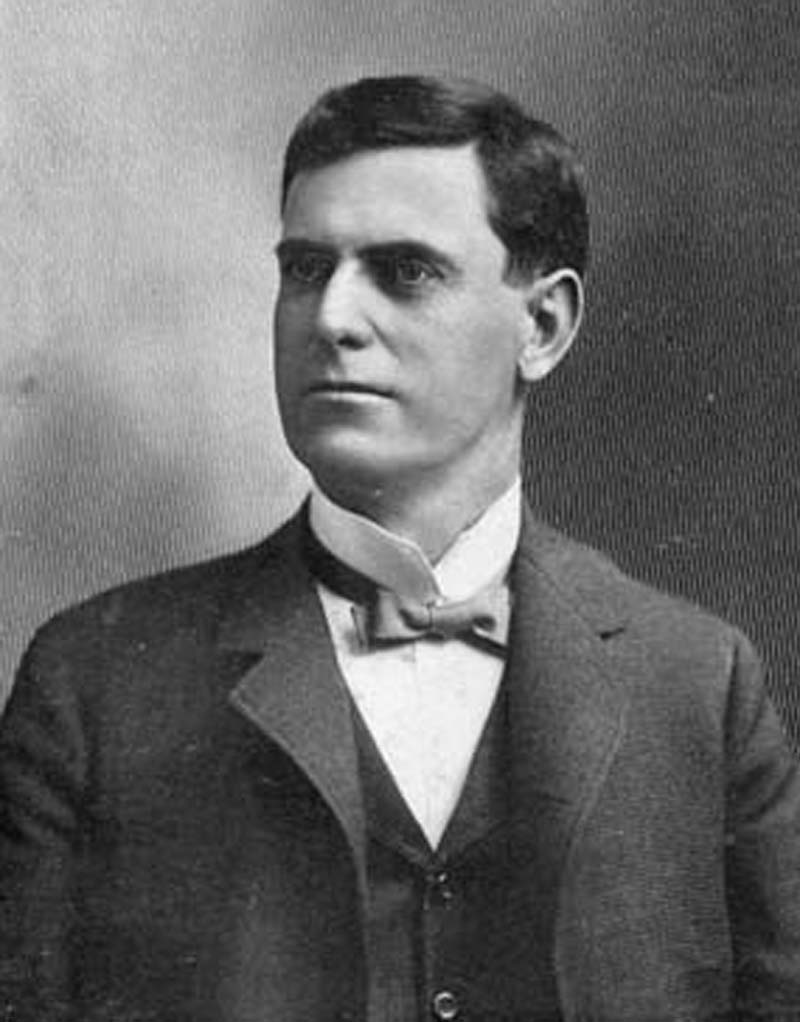

William Mulholland was a brilliant man. Despite having no formal education, he was able to learn geology and engineering. He memorized everything he read, and he excelled at everything he put his mind to. He managed quickly to memorize the entire water system of Los Angeles. Mulholland and Eaton became friends. Mulholland quickly rose up the ladder in the L.A. Water Co. When it became apparent the Los Angeles River was an inadequate source of water for a growing Los Angeles, the search for water was underway.

Mulholland and Eaton went to the Owens Valley where they discovered the mighty Owens River. If they could somehow capture the clear, clean water from this fast-flowing river, all of the water problems Los Angeles faced would be washed away. So, Eaton and Mullholland decided to see if they might be able somehow to divert this river to Los Angeles.

The idea of an aqueduct from the Owens Valley to the San Fernando Valley was proposed. But the city didnít have the water rights. So, Mulholland and Eaton set about buying up all the riparian land along the river that they could. They pretended they were going to use it for a reclamation project, or perhaps for cattle ranching. Eventually, they acquired the rights to more than 50 miles of the riparian corridor. They now had enough land under their control to begin building the aqueduct. Mulholland ceremoniously posed for cameras, holding the first shovel full of dirt. The project was underway. Two hundred and thirty-three miles of aqueduct were constructed. The entire pipeline was downhill all the way from the Owens Valley intake to the San Fernando Valley, where it drained into a reservoir. Theus, no pumps were needed to transport the water. Gravity took care of the transportation.

Mulholland became a celebrated hero to the people of Los Angeles. The city thrived and grew. But the Owens Valley withered. When the people of the distant valley realized they had been duped and that Eaton and Mulholland had virtually stolen their water, the water wars began. Attacks commenced on the aqueduct, and ultimately it was blown up with dynamite. The intake and spillway were damaged, and Mulholland and Eaton realized they needed to store water in various locations around the Los Angeles basin or run the risk of running out of water for a new, thirsty Los Angeles. The last of these dams was the St. Francis, built in San Francisquito Canyon. Many mistakes were made in the construction of the dam.

On the east side, the dam was built upon a Paleolithic landslide. The rock on the east side of the dam was Pelona schist. The western abutment was red Sespe conglomerate that crumbled when wet. The dam was raised in height twice by 10 feet each time, without increasing the diameter of the foundation. Each of these mistakes played a role in the failure of the dam. The height of the dam increased the capacity, which also increased the weight of the water impounded behind the dam. This caused a phenomena called hydro-lift. Under the added water weight, the face of the dam began to lift. The Paleolithic landslide shifted and began to slide, and the Pelona schist crumbled. The Sespe conglomerate on the west side of the dam then crumbled, leading to the ultimate failure of the dam.

The center section remained standing. Curious visitors to the ruins of the dam called this monolith The Tombstone. A 180-foot wall of water left the dam, ravaging property and killing every living thing in its path. When all was said and done, at least 431 people were dead, and the property damage was horrendous. A few people in the flood plain managed to survive. Lilian Curtis, her little son Danny and their dog managed to escape up a hill as the water washed away her husband Lyman and their two daughters. At least one man was saved by clinging to a rooftop being carried away by the raging water.

Edison workers camped near Blue Cut on Highway 126, just this side of the Los Angeles-Ventura county border, were asleep in their tents when the water approached their camp. Eighty-four of the men died as the water and debris enveloped their tents, trapping them. There were a few survivors at this location. The men who had tightly fastened their tents up floated on top of the whirlpool of debris. The flood continued to maim, kill and destroy property all the way to Ventura. The flood was two miles wide at this point, and bodies, bits and pieces of peopleís lives, and debris entered the Pacific Ocean at Montalvo. Fred Eaton died in 1934, nearly a pauper. Mulholland died a year later, in 1935, a broken man, a recluse. The dream of water destroyed both men. After the failure of the S. Francis, dam safety and regulations across the country were scrutinized. The way we built dams after that was influenced in part by what was learned from the St. Francis. Members of the SCV Historical Society is working toward the passage of federal legislation to designate the St. Francis Dam Disaster site a national memorial. If you would like to help, we are collecting letters to send to our congressman in support of this legislation. Please contact me at the email address below, and I will supply you with a sample letter to support this bill. Thank you.

©2016 SCVTV/SCVHistory.com | Dianne Erskine-Hellrigel is executive director of the Community Hiking Club and president of the Santa Clara River Watershed Conservancy. Contact Dianne through communityhikingclub.org or at zuliebear@aol.com.

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.

The Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society hosted a presentation at Heritage Junction Saturday, followed by a bus tour to the St. Francis Dam. The tour completely sold out the first two weeks it was offered. And it was a smashing success.

The Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society hosted a presentation at Heritage Junction Saturday, followed by a bus tour to the St. Francis Dam. The tour completely sold out the first two weeks it was offered. And it was a smashing success.