|

|

William S. Hart

|

Rivoli Theatre program for the Broadway premiere of "Wagon Tracks," August 10, 1919. An Artcraft picture, "Wagon Tracks" was co-produced by its star, William S. Hart, and by Thomas H. Ince (Famous Players-Lasky Corp., later known as Paramount). It was directed by Lambert Hillyer from an original story and screenplay (scenario) by C. Gardner Sullivan. It was released July 29, 1919. Set at the beginning of the California Gold Rush and taking place primarily along the dusty trail (where the wagon makes tracks), this is a story of revenge, in this case for the murder of the Hart character's brother. The love interest (who initially shields the killer) is played by Jane Novak, who was probably also an object of Hart's off-screen affections. Rounding out the cast are Robert McKim, Lloyd Bacon, Leo Pierson, Bert Sprotte and Charles Arling. The Rivoli Theatre performance includes, in addition to orchestral and organ numbers and singing, a short nature or travel film; a newsreel; and a short comedy, "Foxy Ambrose," starring Mack Swain. About the Rivoli and Rivoli Theatres.

The Rialto and Rivoli theaters were sister movie palaces on Broadway that used a full orchestra and grand pipe organ to provide audiences with a complete program including a first-run feature film (often a premiere) plus comedic shorts and newsreels interspersed with musical performances. A new program, initially built around the latest Famous-Players Lasky (Paramount) release, debuted every Sunday. The 1,960-seat Rialto opened April 21, 1916, on the site of Oscar Hammerstein's former Victora Theater, a vaudeville venue, at 1481 Broadway (corner 42nd Street). With its success, on December 28, 1917, owners Crawford Livingston and Felix Kahn opened a second theater, the 2,270-seat Rivoli, a Greek revival building designed by Thomas W. Lamb at 1620 Broadway (corner 49th). Its first show featured the Douglas Fairbanks film, "A Modern Musketeer."

Music was considered central to the program. The Rialto initially used a grand pipe organ built in 1916 by the Austin Organ Co. of Hartford, Conn., Opus 611, which was billed as the largest organ ever installed in a motion picture theater. It was replaced with a 1922 Wurlitzer Opus 520. The Rivoli started with a 1917 Ausin, Opus 709, and replaced it with a 1924 Wurlitzer, Opus 839. In 1926, Paramount built its own eponymous theater on Broadway, and it also controlled the Criterion. There wasn't enough Paramount product to sustain four theaters, so the Rialto and Rivoli started to run films from other distributors. The Great Depression killed the Criterion and the Rialto; the latter closed in 1935 and was rebuilt on a smaller scale. In the 1970s it became an adult movie theater, then switched to live theater in the 1980s and was used as a TV studio before being demolished in 2002 to make way for a high-rise office building.

In 1963, an Egyptian façade was added to the building for the premiere of "Cleopatra." The façade stayed until the 1980s when it was altered to prevent the building from being designated a landmark. In 1981 the curved screen was removed, and in 1984 it became a United Artists Twin theater. UA closed it in June 1987 and the building was demolished in favor of a black glass skyscraper.

About 'Wagon Tracks.' From Koszarski (1980:114): Produced by William S. Hart Productions; advertised as "supervised by Thomas H. Ince"; distributed by Paramount-Artcraft; released July 29, 1919; ©July 21, 1919; five reels (5158 feet). Directed by Lambert Hillyer; story and screenplay by C. Gardner Sullivan; photographed by Joe August; art director, Thomas A. Brierley; art titles, Irwin J. Martin. CAST: William S. Hart (Buckskin Hamilton); Jane Novak (Jane Washburn); Robert McKim (Donald Washburn); Lloyd Bacon (Guy Merton); Leo Pierson (Billy Hamilton); Bertholde Sprotte (Brick Muldoon); Charles Arling (The Captain). SYNOPSIS: The wagon tracks leading to Westport Landing are those of emigrants westward bound during the days of the gold rush. Buckskin Hamilton, a desert guide, comes down to meet the steamer on which he expects his younger brother Billy. On going aboard he learns that he has been killed, the story being that he was shot by Jane Washburn in self-defense. He credits part of the story — it is inconceivable that she deliberately shot him, but he suspects that her gambling brother Donald, and his confederate Merton, had something to do with the killing. These people accompany a long wagon train in the charge of Buckskin. On the desert one of the wagons carrying water falls over a precipice and the entire train is put on short allowance. Buckskin shows so much tender consideration for the weak and helpless at this time that Jane is deeply moved and confesses that the man killed had not annoyed her. Buckskin is now certain she did not do the shooting. He captures Donald and Merton at night, binds them to a lariat and drives them out on the desert to walk until one or the other confesses. They become half-crazed by thirst and accuse each other, the guilt being finally fixed on Donald. A band of Indians nearby has demanded of the emigrants the murderer of one of their number, a man for a man. Buckskin gives Donald the alternative of going to the Indians or of shooting himself. Donald attempts to escape, but is captured by the Indians and taken to the torture. The wagon train goes on now unmolested. On reaching its destination, Jane, who has learned to love Buckskin, seeks to restrain him from going over the trail, but he decides to leave her. She fondly hopes he will come back some day. He regretfully says "mebbe" and returns to his duty. [Moving Picture World, August 23, 1919] REVIEWS: The director saw to it that things were kept within reasonable bounds, even when there were chances to lay things on a bit thick ... it treats of an always romantic phase of American history. Those days back in '49 and '50 have been written, and screened over and over again, but the romance of the Westward trend of Americans is always of interest to the present generation, especially if the story is well presented and has more meat to it than the usual dance-hall mellers. [Wid's, August 17, 1919] A fairly good Hart picture, well constructed by the talented author, Gardner Sullivan, logical and consistent throughout, but dark in mood, presenting Hart in a vindictive and revengeful character... . The motives of revenge, so well suited to Continental audiences, are not so much in use here, possibly because they have been overdone in cheap melodrama, somewhat looked down upon by manly Americans of today... . [Louis Reeves Harrison, Moving Picture World, August 23, 1919]

19200 dpi jpegs from original program purchased 2014 by Leon Worden. |

WATCH FULL MOVIES

Biography

(Mitchell 1955)

Narrated Biopic 1960

Biography (Conlon/ McCallum 1960)

Biography (Child, NHMLA 1987)

Essay: The Good Bad Man (Griffith & Mayer 1957)

Film Bio, Russia 1926

The Disciple 1915/1923

The Captive God 1916 x2

The Aryan 1916 x2

The Primal Lure 1916

The Apostle of Vengeance (Mult.)

Return of Draw Egan 1916 x2

Truthful Tulliver 1917

The Gun Fighter 1917 (mult.)

Wolf Lowry 1917

The Narrow Trail 1917 (mult.)

Wolves of the Rail 1918

Riddle Gawne 1918 (mult.)

"A Bullet for Berlin" 1918 (4th Series)

The Border Wireless 1918 (Mult.)

Branding Broadway 1918 x2

Breed of Men 2-2-1919 Rivoli Premiere

The Poppy Girl's Husband 3-23-1919 Rivoli Premiere

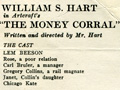

The Money Corral 4-20-1919 Rialto Premiere

Square Deal Sanderson 1919

Wagon Tracks 1919 x3

Sand 1920 Lantern Slide Image

The Toll Gate 1920 (Mult.)

The Cradle of Courage 1920

The Testing Block 1920:

Slides, Lobby Cards, Photos (Mult.)

O'Malley/Mounted 1921 (Mult.)

The Whistle 1921 (Mult.)

White Oak 1921 (Mult.)

Travelin' On 1921/22 (Mult.)

Three Word Brand 1921

Wild Bill Hickok 1923 x2

Singer Jim McKee 1924 (Mult.)

"Tumbleweeds" 1925/1939

Hart Speaks: Fox Newsreel Outtakes 1930

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.