|

|

Pico Canyon Oil Pioneer

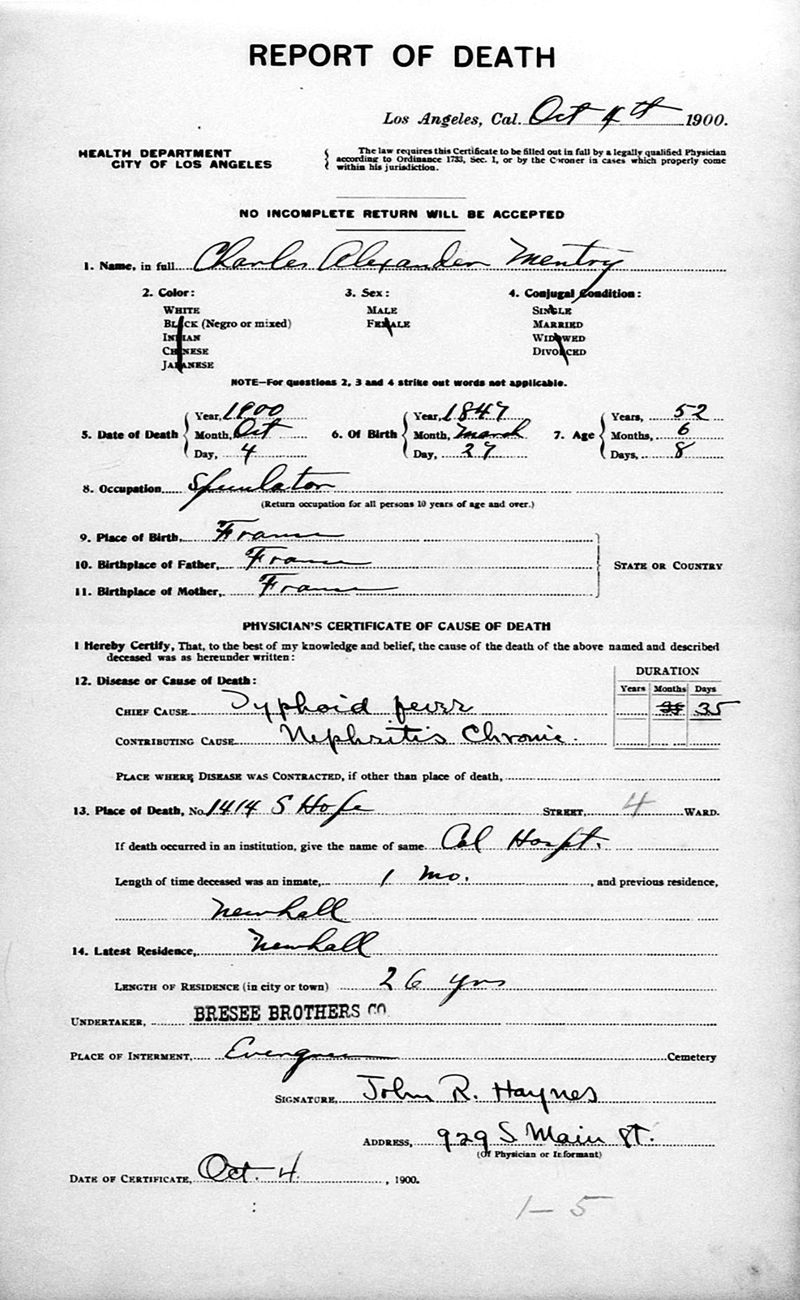

Click image to enlarge For years and years, we thought the pioneering Pico Canyon oil driller Charles Alexander "Alec" Mentry died from an allergic reaction to a bee sting. Then, around the year 2000, roughly the 100th anniversary of his death, we learned another story, purportedly passed down from his daughter-in-law. It said Mentry was repeatedly bitten on the lips by conenose bugs (genus Triatominae) — thus their alternate name, kissing bugs — and he went to the hospital, contracted pneumonia or liver failure or both, and died. Either story was fairly plausible; bees and conenose bugs are prevalent in Pico Canyon. Now (2014) comes historian Ann Stansell with Mentry's actual death certificate showing neither insect was the proximate cause of the driller's death. Was he stung by bees? Maybe. Was he bitten on the lips by bugs? Stranger things have happened. But according to the attending physician, John R. Haynes of 929 S. Main St., Los Angeles, Alec Mentry died at California Hospital, 1414 S. Hope St., as a result of typhoid fever, with chronic nephritis as a contributing factor. So at least the idea of liver failure was sort of close. Nephritis is kidney disease. According to Dr. Alan Pollack, who is both a Santa Clarita historian and a physician, chronic (preexisting) kidney disease would have nothing to do with a bug bite — and neither would typhoid fever, which would likely have come from something he ate or drank. "Maybe (the daughter-in-law) associated the bug bite with his worsening condition, but in fact he was suffering the effects of typhoid fever," Pollack posits. "The bug bite, if it truly occurred, could have been a red herring or coincidence." Moreover, Pollack says: "If the doctors were convinced that he died from an allergic reaction and pneumonia from a bug bite, at the least they would have listed anaphylactic shock and pneumonia on the death certificate." They didn't. They said he succumbed to typhoid fever after contracting it 35 days earlier and being hospitalized for all or most of that time ("1 mo."). They don't say how long his kidneys had been bothering him. A 35-day period of illness is consistent with the characteristics of typhoid fever, Pollack says. "Today," Pollack writes, "typhoid fever is treated with and responds well to antibiotics, but there were no antibiotics in 1900. Alex Mentry may have suffered an untreated and fatal course of typhoid fever which lasted a typical 35 days. "In the first week, he may have experienced intense abdominal pain, constipation, cough, headache, delirium and a stuporous mental state. By the end of the first week, he could have had fevers to 104 degrees and a rash. These symptoms typically worsen in the second week. The third week might have found him even sicker, not eating, having diarrhea and losing weight. He could have become confused and even psychotic. Death usually occurs in the fourth week due to overwhelming infection, inflammation of the heart or bleeding in the intestine. "Of note, typhoid fever can be passed only from human to human via contaminated food, water or hands. Therefore no bug could have given Alex Mentry typhoid fever." At least the date is consistent with our records. It shows he died Oct. 4, 1900. The certificate gives a birth date of March 27, 1847, making him 52 years, 6 months and 8 days old at time of death. Born in France to parents who were also born in France, he's listed as white, male, and married. His stated occupation is "speculator" — which of course refers to oil exploration but also provides editorial comment on the way we've handled his cause of death up to this point. Born Charles Alexander Menetrier (maybe) in France on March 27, 1847 (probably), "Alex" Mentry came to the Newhall area in in 1873 to find his fortune. Already an experienced oil driller who had punched 42 successful wells near Titusville, Penn., Mentry soon landed a job digging wells in Grapevine Canyon, at the southern end of the Santa Clarita Valley. In 1875 he formed a partnership to purchase a claim in nearby Pico Canyon, which had been explored in the late 1860s by Newhall entrepreneurs Sanford Lyon, Henry Clay Wiley and Los Angeles lawman William Jenkins. The claim had produced only moderate results, but it held great potential if only someone with sufficient technical and engineering skills would come along to work on it. That man was Alex Mentry, who punched four new wells (Pico No. 1-4) near the old Lyon-Wiley-Jenkins hole. It wasn't long before a San Francisco fiancier by the name of Demetrius Scofield — himself an old Pennsylvania oil man — caught wind of what was going on outside the sleepy burgh of Newhall. Scofield purchased Mentry's claim in 1876 and convinced the oil driller to come into his employ. Mentry used what may have been California's first steam-powered oil rig to drill a fourth well, which consistenly produced 30 barrels of oil per day. Mentry kept digging. Finally, on September 26, 1876, from a depth of 617 feet, a mighty geyser of oil shot through the 5 5/8-inch casing of his No. 4 well. It was the first commercially successful oil well in the western United States, and Demetrius Scofield was a rich man. Teams of oil workers flocked to Pico Canyon, which was soon being called Mentryville. Alex Mentry married Flora May Lake of New York, who gave him three sons and a daughter. They lived in a 13-room Victorian mansion at the base of the canyon. In 1900, Mentry, already suffering from chronic kidney disease, contracted typhoid fever and was hospitalized in Los Anglees, where he died Oct. 4. He was laid to rest in the Evergreen Cemetery in Boyle Heights, where other family members are also interred. Information from Chevron/Standard Oil records; published works of A.B. Perkins; and "Pico Canyon Chronicles: The Story of California's Pioneer Oil Field" by Jerry Reynolds. Cemetery information from Jack and Joan Beitzel. Further reading: The Story of Mentryville.

AS0001: 19200 dpi jpeg from smaller jpeg. |

Eulogy by Scofield

Death of Son Arthur 1954

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.