Mentryville: Pioneer Oil Town.

California Registered Historical Landmark No. 516-2.

|

Webmaster's note.

The town of Mentryville was officially designated California State Historical Landmark No. 516-2 on this date (October 8, 1977). Number 516 was the Pico No. 4 oil well, located 1.4 miles to the east in Pico Canyon. It was designated November 25, 1953. The Pico Canyon oil field, including the No. 4 oil well and the town of Mentryville, is also a National Historic Landmark, designated November 13, 1966.

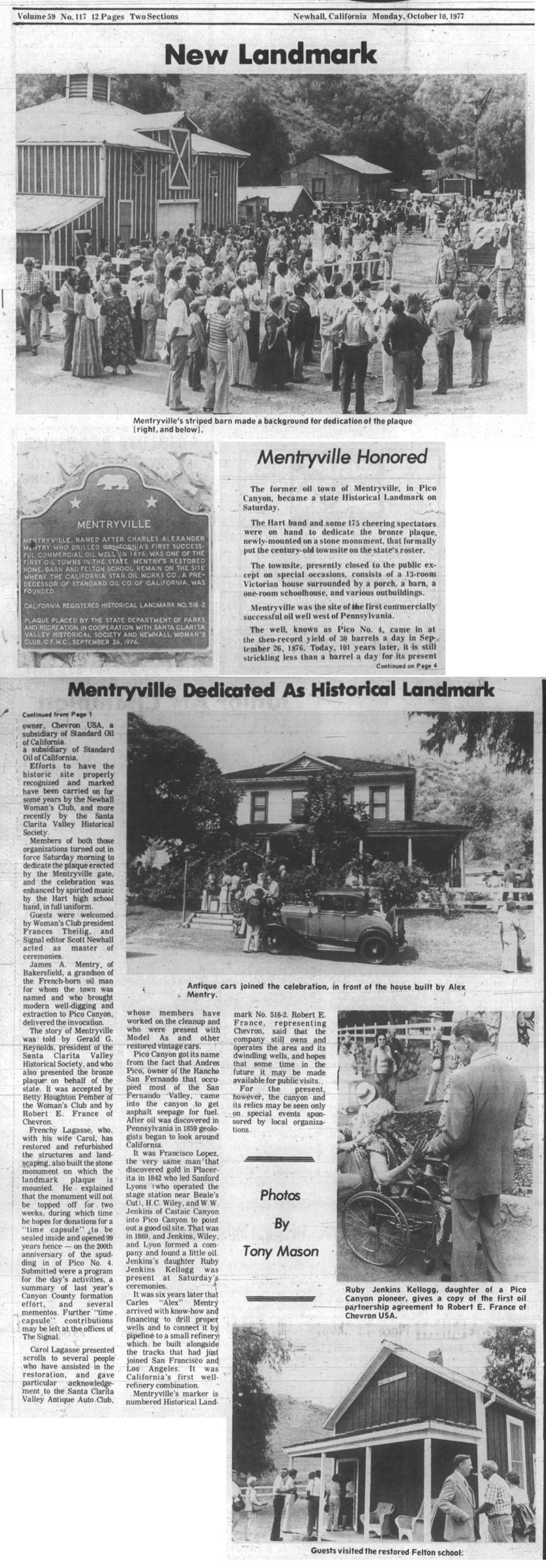

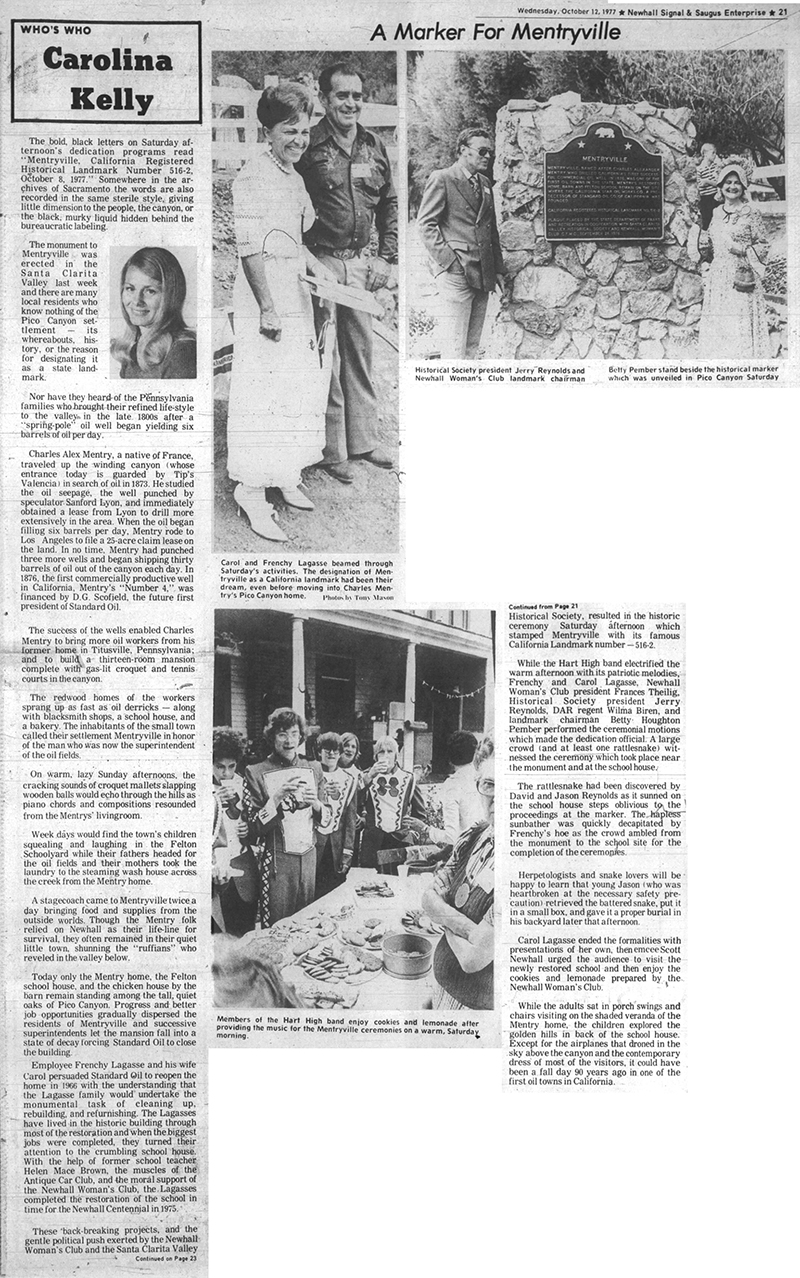

Mentryville Dedicated as Historical Landmark. The Signal | Monday, October 10, 1977. The former oil town of Mentryville in Pico Canyon became a state Historical Landmark on Saturday. The Hart band and some 175 cheering spectators were on hand to dedicate the bronze plaque, newly mounted on a stone monument, that formally put the century-old townsite on the state's roster. The townsite, presently closed to the public except on special occasions, consists of a 13-room Victorian house surrounded by a porch, a barn, a one-room schoolhouse, and various outbuildings. Mentryville was the site of the first commercially successful oil well west of Pennsylvania. The well, known as Pico No. 4, came in at the then-record yield of 30 barrels a day on September 26, 1876. Today, 101 years later, it is still trickling less than a barrel a day for its present owner, Chevron USA, a subsidiary of Standard Oil of California [sic; Standard rebranded itself as Chevron USA in 1977]. Efforts to have the historic site properly recognized and marked have been carried on for some years by the Newhall Woman's Club, and more recently by the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society [the latter was newly formed in 1975; the former was considerably older — Ed.]. Members of both those organizations turned out in force Saturday morning to dedicate the plaque erected by the Mentryville gate, and the celebration was enhanced by spirited music by the Hart high school band, in full uniform. Guests were welcomed by Woman's Club president Frances Theilig, and Signal editor Scott Newhall acted as master of ceremonies. James A. Mentry of Bakersfield, a grandson of the French-born oil man for whom the town was named and who brought modern well-digging and extraction to Pico Canyon, delivered the invocation. The story of Mentryville was told by Gerald G. Reynolds, president of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society, and who also presented the bronze plaque on behalf of the state. It was accepted by Betty Houghton Pember of the Woman's Club and by Robert E. France of Chevron. Frenchy Lagasse, who, with his wife Carol, has restored and refurbished the structures and landscaping, also built the stone monument on which the landmark plaque is mounted. He explained that the monument will not be topped off for two weeks, during which time he hopes for donations for a "time capsule" to be sealed inside and opened 99 years hence — on the 200th anniversary of the spudding in of Pico No. 4. Submitted were a program for the day's activities, a summary of last year's Canyon County formation effort, and several mementos. Further "time capsule" contributions may be left at the offices of The Signal. Carol Lagasse presented scrolls to several people who have assisted in the restoration and gave particular acknowledgement to the Santa Clarita Valley Antique Auto Club, whose members have worked on the cleanup and who were present with Model A's and other restored vintage cars. Pico Canyon got its name from the fact that Andres Pico, owner of the Rancho San Fernando that occupied most of the San Fernando Valley, came into the canyon to get asphalt seepage for fuel. After oil was discovered in Pennsylvania in 1859, geologists began to look around California. It was Francisco Lopez, the very same man who discovered gold in Placerita in 1842, who led Sanford Lyon (who operated the stage station near Beale's Cut), H.C. Wiley and W.W. Jenkins of Castaic Canyon into Pico Canyon to point out a good oil site. That was in 1869, and Jenkins, Wiley and Lyon formed a company and found a little oil. Jenkins' daughter Ruby Jenkins Kellogg was present at Saturday's ceremonies. It was six years later that Charles "Alex" Mentry arrived with know-how and financing to drill proper wells and to connect it by pipeline to a small refinery which he built alongside the tracks that had just joined San Francisco and Los Angeles. It was California's first well-refinery combination. Mentryville's marker is numbered Historical Landmark No. 516-2. Robert E. France, representing Chevron, said that the company still owns and operates the area and its dwindling wells, and hopes that sometime in the future it may be made available for public visits. For the present, however, the canyon and its relics may be seen only on special events sponsored by local organizations.

A Marker for Mentryville The Signal | Wednesday, October 12, 1977. The bold, black letters on Saturday afternoon's dedication programs read "Mentryville / California Registered Historical Landmark Number 516-2 / October 8. 1977." Somewhere in the archives of Sacramento the words are also recorded in the same sterile style, giving little dimension to the people, the canyon, or the black, murky liquid hidden behind the bureaucratic labeling. The monument to Mentryville was erected in the Santa Clarita Valley last week, and there are many local residents who know nothing of the Pico Canyon settlement — its whereabouts, history, or the reason for designating it as a state landmark. Nor have they heard of the Pennsylvania families who brought their refined lifestyle to the valley in the late 1800s after a "spring-pole" oil well began yielding six barrels of oil per day. Charles Alex Mentry, a native of France, traveled up the winding canyon (whose entrance today is guarded by Tip's Valencia) in search of oil in 1873. He studied the oil seepage, the well punched by speculator Stanford Lyon, and immediately obtained a lease from Lyon to drill more extensively in the area. When the oil began filling six barrels per day, Mentry rode to Los Angeles to file a 25-acre claim lease on the land. In no time, Mentry had punched three more wells and began shipping thirty barrels of oil out of the canyon each day. In 1876, the first commercially productive well in California, Mentry's "Number 4," was financed by D.G. Scofield, the future first president of Standard Oil. The success of the wells enabled Charles Mentry to bring more oil workers from his former home in Titusville, Pennsylvania; and to build a thirteen-room mansion complete with gas-lit croquet and tennis courts in the canyon. The redwood homes of the workers sprang up as last as oil derricks — along with blacksmith shops, a schoolhouse, and a bakery. The inhabitants of the small town called their settlement Mentryville in honor of the man who was now the superintendent of the oil fields. On warm, lazy Sunday afternoons, the cracking sounds of croquet mallets slapping wooden balls would echo through the hills as piano chords and compositions resounded from the Mentrys' living room. Weekdays would find the town's children squealing and laughing in the Felton Schoolyard while their fathers headed for the oil fields and their mothers took the laundry to the steaming wash house across the creek from the Mentry home. A stagecoach came to Mentryville twice a day bringing food and supplies from the outside worlds. Though the Mentry folk relied on Newhall as their lifeline for survival, they often remained in their quiet little town, shunning the "ruffians" who reveled in the valley below. Today only the Mentry home, the Felton schoolhouse and the chicken house by the barn remain standing among the tall, quiet oaks of Pico Canyon. Progress and better job opportunities gradually dispersed the residents of Mentryville, and successive superintendents let the mansion fall into a state of decay, forcing Standard Oil to close the building. Employee Frenchy Lagasse and his wife Carol persuaded Standard Oil to reopen the home in 1966 with the understanding that the Lagasse family would undertake the monumental task of cleaning up, rebuilding, and refurnishing. The Lagasses have lived in the historic building through most of the restoration, and when the biggest jobs were completed, they turned their attention to the crumbling schoolhouse. With the help of former schoolteacher Helen Mace Brown, the muscles of the Antique Car Club, and the moral support of the Newhall Woman's Club, the Lagasses completed the restoration of the school in time for the Newhall Centennial in 1975. These back-breaking projects, and the gentle political push exerted by the Newhall Woman's Club and the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society, resulted in the historic ceremony Saturday afternoon which stamped Mentryville with its famous California Landmark number: 516-2. While the Hart High band electrified the warm afternoon with its patriotic melodies, Frenchy and Carol Lagasse, Newhall Woman's Club president Frances Theilig, Historical Society president Jerry Reynolds, DAR regent Wilma Biren, and landmark chairman Betty Houghton Pember performed the ceremonial motions which made the dedication official. A large crowd (and at least one rattlesnake) witnessed the ceremony which took place near the monument and at the schoolhouse. The rattlesnake had been discovered by David and Jason Reynolds as it sunned on the schoolhouse steps, oblivious of the proceedings at the marker. The hapless sunbather was quickly decapitated by Frenchy's hoe as the crowd ambled from the monument to the school site for the completion of the ceremonies. Herpetologists and snake lovers will be happy to learn that young Jason (who was heartbroken at the necessary safety precaution) retrieved the battered snake, put it in a small box, and gave it a proper burial in his backyard later that afternoon. Carol Lagasse ended the formalities with presentations of her own; then, emcee Scott Newhall urged the audience to visit the newly restored school and then enjoy the cookies and lemonade prepared by the Newhall Woman's Club. While the adults sat in porch swings and chairs visiting on the shaded veranda of the Mentry home, the children explored the golden hills in back of the schoolhouse. Except for the airplanes that droned in the sky above the canyon and the contemporary dress of most of the visitors, it could have been a fall day 90 years ago in one of the first oil towns in California.

CN7701: Download individual pages here. Program book donated 2019 by Cynthia Neal-Harris to the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society.

|