|

|

Green Garden Stone Above Old Ravenna.

By Jay Ellis Ransom.

Photographs by the author

Map by Norton Allen

Desert magazine | Vol. 20 No. 2, February 1957.

|

Collecting stones for the home rock garden and for path and drive borders is one of the most enjoyable and rewarding phases of the gem and mineral hobby. Recently Jay Ransom made a trip to Soledad Canyon on the edge of Southern California's Mojave Desert — not for garden stone, but for moss agate also found in the area. So beautiful and accessible, however, was the emerald green waxy quartz vein of rock garden material he discovered, the quest for the much-prized agate became secondary.

Going through an old California guide book recently, I came across a description of the community of Ravenna in Soledad Canyon four miles southwest of Acton: "Ravenna: population 32, an old settlement, quaint and hospitable, famous for its moss agates and grizzly bears." Recalling the mountainous country around Mint and Soledad Canyons, almost devoid of vegetation, I could not imagine what a hungry grizzly would feed on. More likely, in the days of the Spanish land grants, the creatures were predators feasting on the herds of long-horn cattle. Today, if even a ghost of a grizzly bear remains in the neighborhood, it must be holed up in the rugged mine-gouged mountains that rise so steeply from both sides of Soledad Canyon. But moss agates are bears of another breed. I've tramped along the Yellowstone in Montana looking for the beautiful black-moss agates, and have garnered a fair share of red-plume agates from south-central Utah. Ransom Senior has picked up just about every other kind of agate there is in the nation from most of the known sources as well as from a lot of other fascinating places kept secret by their jealous claimants. We decided to visit Ravenna and see for ourselves what kinds of rocks there might be there. We located the moss agates, all right, along the bottom of Soledad Canyon where old stream gravels carry water during the rainy season. But we found more than that to interest us — rock garden material of unusual beauty.

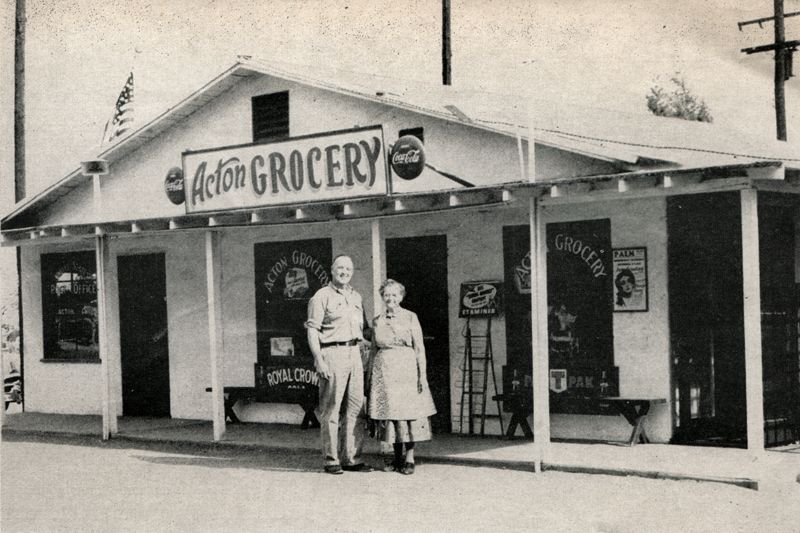

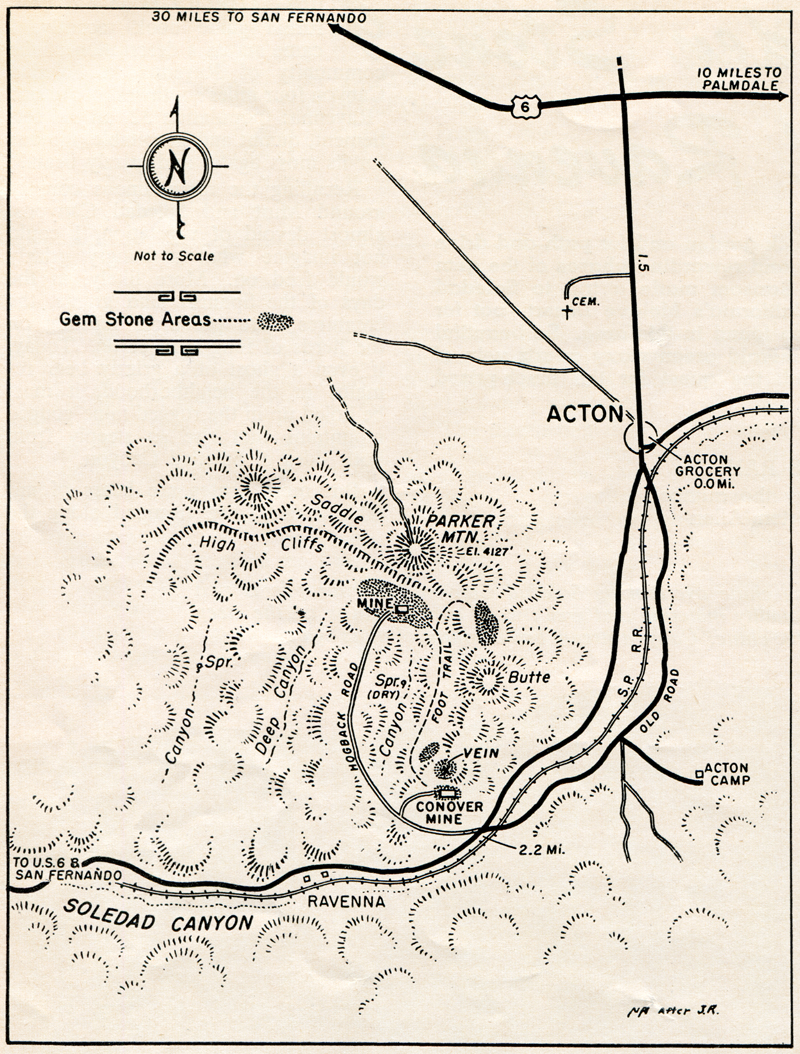

It was my neighbor across the street who unwittingly changed the course of this rock trip. He has a garden, one he proudly refers to as "the rock garden." He doesn't know an agate from a horned toad, but he recognizes a pretty rock when he sees one. And like him, there is a vigorous fraternity of folks who collect pretty rocks as rock garden décor. If a stone has color who cares what its technical name is? Consequently, when we discovered a four-foot vein of beautiful green silica, we lost interest in grubbing around for mere gem stones. There, above the abandoned workings of the Conover Mine, this vein, like an enormous banded emerald scintillating in the bright sunshine, had not been excavated by miners, but quite obviously by rock collectors. Frank Frauenberger, 57, helped us become oriented in the Ravenna-Acton area. Frank used to sell us gasoline in Hermosa Beach, but tiring of big city life he took his attractive wife Fannie and emigrated up Mint Canyon to Acton where they took over the combination grocer, postoffice and service station. Frank greeted us enthusiastically — tall, big-boned, as genial a host as we could find anywhere. His wife was busy behind the grocery-laden counter talking with customers. Seeing our puzzled expressions, Frank explained: "Fannie has been enjoying herself more since she took over the store than I ever thought she could a year ago. She didn't have enough to do back in the city to occupy her time." He looked fondly over at his wife putting groceries into a bag. "Of course, she didn't like it here at first. Too raw a desert, and so dry. She didn't know anybody and she wasn't at all happy. But not for long. Before I knew it she was acquainted with most everybody in this whole trading area — must be a thousand folks or more — and was calling ‘em all by their first names. It made a change in her, too." What brought Frank Frauenberger back to the Mojave was what takes a lot of older folks back to childhood scenes — a nostalgia for old remembered things, people and places. Frank's father, William, took up a homestead here in 1919 known as the Monte Grande Ranch. It lies along the railroad about three miles down Soledad Canyon from the postoffice. There for some years the elder Frauenberger raised chickens and turkeys. "The ranch is near the old Fort Tejon stage road built through these mountains," Frank said. "Today, of course, most of the old road is gone and the Southern Pacific Railroad comes through in its stead." The family later settled in Hermosa Beach where Frank's father still resides in good health. But each year, father, brother, sister and Frank, whenever he could get away from his service station, returned to the old desert homestead for their vacations. "I should have moved back here long ago," Frank said, ruefully. "It's healthy for both of us out here; hot as blazes in summer, sometimes pretty cold and snowy in winter on account of the elevation but find country to live in." Frank has not had time to learn a great deal about gem stones although he has accumulated quite a store of information. Whenever a rockhound drops into his store for a cooling drink, he's ready with all the local gossip about where to look for gem stone materials. It seems that the mining-minded residents confide in Frank. His own interest lies more in rock garden material, and he keeps the grounds around his store and adjacent home as neat as he ever did his city property. It was he who told us about the Conover Copper mine up the steep slant of the mountain from Ravenna. We drove south and west 2.2 miles — about two-thirds of the way to Ravenna — over the new Soledad Canyon road. This is a very fine new paved highway that replaces the old winding Soledad asphalt. The old road crosses the railroad tracks just south of Acton and, circling past a county honor farm, re-crosses the track onto the new highway at mile 2.2, almost in front of the entry road through the fence onto Conover Mine property. At the entrance, from which any gate that might have hung at one time had long vanished, we turned in and drove up the dim tracks one-tenth of a mile.

Parking is easy along the lower portion of the road. From there, the hike along the old deeply eroded tracks to the Conover Mine was not difficult. Mines in the Soledad area were best known for their production of gold, copper and silver found in bull quartz veins. The basal rocks exposed in the region appear to be andesite of late Mesozoic age associated with the Miocene sandstones and quartz monzonite. It's truck rock hunting country. All up and down the precipitous slopes we round chunks of green silica float — massive quartz deeply stained with an emerald translucence, waxy like jade and cool to the touch. As we hiked upward, Ransom Sr. continually picked up specimens and tested them with his prospector's hammer, sometimes exclaiming over the color and texture. Pausing frequently to take a breather gave me an opportunity to look over the country. Below us Soledad Canyon wound in a tremendous gorge through the mountains, hardly more than a quarter mile wide. We looked almost straight down upon the county farm and the community of Ravenna strung out green with shade trees along the railroad tracks and the highway. In the bright morning sunlight the valley scene was peaceful. Beyond, the ragged bulk of the mountains lifted along the ancient San Andreas fault. The stood etched in soft pastel blue haze that pervaded the morning air from railroad engines which had chuffed through the canyon spewing their smoke and exhaust into the crisp dawn. On all sides the mountains whirred with the quick darting movements of quail. Some scuttled deeper into the creosote bushes at our approach while others, mottled in gray and brown and startled by our sudden appearance took wing and circled out over the canyon depths with wildly beating ruffed wings. An occasional jackrabbit lifted in erratic flight, only to crouch behind a distant bush where he surveyed us with beady, suspicious eyes.

The Conover Mine was nothing much to look at. In production for several years, it was a patented mine which belonged to the Tonopah Milling and Mining Company in 1927-28. Later, two men, Crawford and Gage, secured the right to reopen it and they took out ore at various times, the last mining being done in 1949. Now there is nothing left but the loading chute, a few horizontal tunnels that wander off into the depths of the mountain, and the narrow railroad bed leading to the slag dump. Even the tracks have been taken up and sold. Remaining, however, is an abundance of beautiful green copper quartz scattered everywhere. And, to our pleasant surprise and delight, on the almost vertical declivity immediately above the lower tunnel we stumbled across a massive outcrop, as deep green emerald in color as the farms veiled in the canyon haze. This outcrop does not appear to have been mined, although the small excavations about it seem the sort ambitious but ill-equipped rockhounds make. The four-foot vein strikes steeply into a mountain flank. It is a mineral vein which would interest all gem stone collectors, but because of the mass of rock present, it is of even greater interest to rock garden enthusiasts. We scrambled up the rugged slope hand over foot, slipping and sliding. A misstep could have sent us tumbling hundreds of feet down the smooth slope. Although the nearby mountains are ringed with high basalt cliffs topped by Parker Peak, we found outcrops of massive green quartz beyond the Conover. Weathered and fractured granite surfaced here and there. The cul-de-sac valley that rises steeply by sharp narrow canyons and ragged hogbbacks to the forbidding cliffs was characterized by the deep red lava coloration. Exploring along a well-defined foot rail from the Conover Mine up the slant of the mountain by easy stages toward Parker Peak, we searched for float. We found plenty of green silica but little else. A road, scarcely more than the weathered remnants of a wheeled track, climbed below us, slanting up a hogback toward the bluffs where additional mine workings exist. Below the cirque of cliffs to our west lay the rusty, broken segments of a water line reaching for the cottonwoods and willows that disclosed a spring.

There are gem stone minerals in the upper reaches of the cul-de-sac; not only green quartz from the mines, but agate, chalcedony, chalcopyrite, spar and possibly a little serpentine. Indian Tom of the Oasis Ranch in Lawndale, an old time prospector who has explored every foot of this canyon, showed us some head-size rock garden chunks he had picked up at the base of the Parker Mountain cliffs. He said the Conover vein was as nothing compared to the emerald quartz at the head of the canyon. Parker Peak and its sister knob, connected by a high rocky saddle that breaks sheer in undershot cliffs, is a source of copper. The old mines were located along a feldspar-like contact. Not truly feldspar, this was some very hard white rock which, while not quartz either, makes good rock garden material. In the immediate area and of interest to the gem stone savants, there has also been found here some good grade blue bornite mixed with pyrites. Some years ago a mining firm removed four or five thousand tons of feldspathic material for use in surfacing golf courses. This is a beautiful blue-green mineral easily obtained by gravity feed down the steep slopes on the north side of the Conover Mine butte. The trail shown on the map leads to the excavations. This green rock is excellent for rock gardens, and there is plenty of it left. As Frank Frauenberger reported to us, it is one of the finest decorative rocks for gardens in the country. Our observation is that some of it also would cut into cabochons. Although we did not look for it, there is a road reaching the site from Acton. Inquiry is necessary to locate it. About a half mile north of the Conover Mine at the base of Parker Peak is a 500-foot tunnel penetrating the mountain and cleaned of debris several years ago. One can walk all the way in with safety. Immediately above the tunnel entrance is an outcrop of pure bead copper, scattered though the matrix like shiny metal pin heads. It would have taken several days and gallons of drinking water to explore all the gorges and hogbacks. So, returning to the car laden with colorful specimens, we drove back to Acton to say goodbye to Frank and to show him our samples of rock gardeners' delight. |

Copper Hill Mining Co. Stock Cert 1863

Occidental Copper Mining Co. Stock Cert 1863

• Minerals of Mint Canyon (Pacific Mineralogist 12/1941)

1966 Rockhounding Guide

Loading Chute

Gemstone Map

Copper Vein

Mine Shaft

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.