History of Liquor Pay-off Case as Told in True Bill.

Total of 41 Overt Acts and 67 Felony Counts Set Forth in 156-Page Document Accusing Seven.

Los Angeles Times | Friday Morning, November 10, 1939.

Click to enlarge.

|

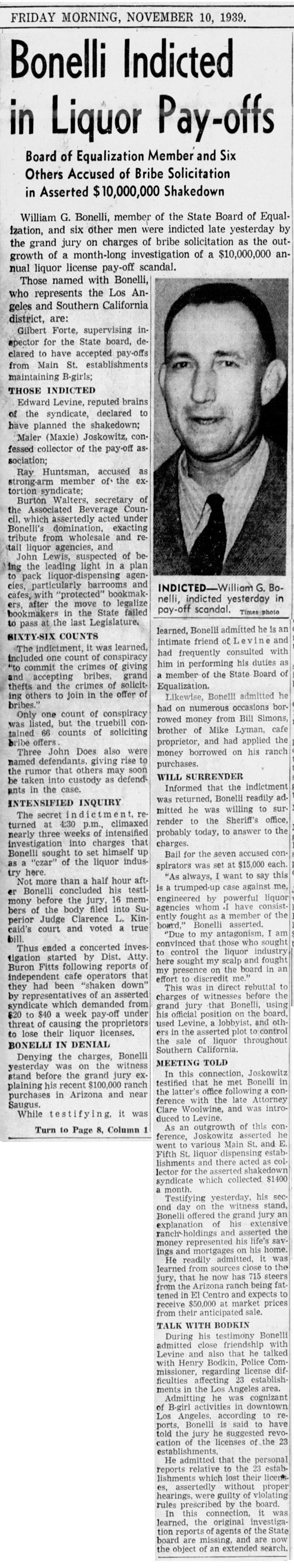

Politics, dating back to the time when William G. Bonelli was running for office on the State Board of Equalization in 1938, forms the background of the indictment returned by the county grand jury yesterday naming Bonelli, six others and three John Does as defendants.

They are charged with conspiracy and 66 counts of soliciting commission of a crime — bribery.

The true bill sets forth 41 overt acts and 67 felony counts in 156 pages of typewritten matter.

The first scene of the dramatic picture is placed in Los Angeles on or about Aug. 1, 1938, when the late Clare Woolwine, attorney, assertedly had a conversation with Maier Joskowitz suggesting that he contribute funds to Bonelli's campaign.

Joskowitz, also known as the Mayor of Main St., promised to give Woolwine about $500 for Bonelli's campaign fund, but insisted upon meeting the man personally, according to the indictment.

The next day, it is charged, Joskowitz met Woolwine and went to Bonelli's office where he was introduced to Edward E. Levine and that several days later gave Attorney Woolwine $500 for having introduced him to Levine and Bonelli.

Shortly afterward, according to the indictment, Joskowitz went to Levine's office and stated that he was having trouble getting his liquor licenses straightened out and requested Levine's aid. The licenses were soon restored to good standing, it is charged, as a result of this arrangement.

From this beginning, the situation soon developed into a wholesale graft scheme, the indictment charges, for Irvine assertedly called Joskowitz to his office and asked that he go to certain Los Angeles cafes operating with B-girls and raise money to pay off a deficit in Bonelli's campaign fund.

Declaring that his honesty might be questioned by the cafe owners, Joskowitz suggested that Gilbert Forte, supervisor of the downtown district for the Board of Equalization, accompany him to lend authenticity to their visits. Thereafter, it is charged, Levine arranged a meeting between the two men and they went out and collected $650 from cafe owners, $350 of which was handed over to Levine.

Not long afterward, the indictment charges, Levine again called Joskowitz to his office and told him that he and other cafe owners in downtown Los Angeles operating with B-girls would have to pay so much a week to operate or lose their licenses, and again Joskowitz and Forte went out and collected funds from cafe owners, which they handed to Levine.

The true bill accuses Levine of demanding $25 a week from small cafes and more from larger ones.

Beginning in January, last, these collections were made regularly, it is charged, under threats that certain E. Fifth St. cafe owners would be closed up by the Board of Equalization unless they paid the money. In delivering these collections to Levine, Joskowitz and Forte were told that Bonelli would get his share, according to the indictment.

Listed as some of the cafe owners who paid money to the two men are Don Ritton, Sam Webber, Tona Ness, William Ness, Sam Mellos, Bert Wadley, Joe Cooper, Ben Gold, Max Silverman and William Mitchener. The payments assertedly ranged from S10 to $40 a week.

Levine then ordered that similar collections be made from Main St. cafe owners, it is charged, and Joskowitz and Forte began collecting money from them so successfully that the total collections reached $350 a week, and soon afterwards when Levine left town, he received $1,100 a month from Joskowitz and Forte.

When rumors of investigation into the situation were heard, Attorney Woolwine cautioned Joskowitz and Forte to have the money paid to another attorney, Louis Most, the indictment asserts, and have him give a receipt to the cafe owners once a month "for legal services."

But, according to the grand jury's accusation, Levine called Joskowitz to his office and declared:

"I have heard that you and other cafe owners and operators who have been paying this weekly pay-off are now paying the money and giving the money to a lawyer to make it look good. The Boss doesn't like that. He thinks that it is dangerous to have a lawyer mixed up in this and you will have to stop that."

It was stopped, and thereafter Ray Huntsman was chosen to receive the money, receiving a fee of $25 a week to collect it under an agreement with Joskowitz.

Then trouble appeared over the horizon and Joskowitz, it is charged, went to Levine saying:

"Things are getting pretty hot in the city. The city might cause us some trouble and has caused some trouble to some of the people that have been paying off. I am getting worried. What can we do about it?"

"Don't worry," Levine assertedly answered. "The city is being taken care of by Ray Haight." (Haight was then a member of Mayor Bowron's Police Commission.)

The indictment then charges that the conspiracy broadened after that, and Irvine asked Joskowitz to get him a list of all places on Seventh and Hill St. operating with B-girls and Max Silverman went with Joskowitz on a survey of the districts to obtain the list.

Fear again besieged Joskowitz, according to the grand juror's charges, for he assertedly went to Levine and said that he believed he was being followed and that the city intended to close many of the places operating with B-girls and Levine assertedly told him, "Well, I will have to see the boss."

It was finally decided, the grand jury charges, that a notice should be sent to all establishments in the downtown districts to discontinue the practice of using B-girls at midnight, Aug. 5, 1939, and the order was delivered to all such cafe operators.

Christmas was not overlooked by Joskowitz, either, it is charged, for among the overt acts the grand jury sets up a charge that Joskowitz, in furtherance of the conspiracy, purchased three pairs of pajamas for Bonelli, Levine and Woolwine and had their initials embroidered on them for Christmas gifts in 1938.

At this time the B-girl situation in Los Angeles became such a subject of controversy that steps were taken to provide an alibi by causing revocation of licenses of other places operating with them that had not been paying off, the grand jury charges.

A list of names of such places submitted to the State Board of Equalization in Sacramento resulted in their licenses being revoked, the indictment states. But two of the names on this list, Samuel W. Wershub, 324 S. Main' St., and Charles Roselli, 614 E. Seventh St., were placed on the list by mistake and when Joskowitz informed Levine of the error, their licenses were restored, at once, according to the true bill.

The indictment also sets forth other overt acts supporting its charge that the defendants entered into a conspiracy seeking money from eastern wholesale liquor distributors and held numerous meetings with William Simon, Parker S. Childs, Gus Kallas and others and received certain sums of money, the amount of which is unknown to the grand jurors.

As a result of this phase of the conspiracy, it is charged, licenses were suspended in California for the National Distillers Products Corp., Frankfort Distilleries Inc., and Schenley Distilleries Inc.

Thereafter, the indictment states, the licenses of 23 retail liquor dealers were suspended, a charge was placed against McKesson & Robbins Inc., charging violation of the Alcoholic Beverage Control Act, and a similar charge was placed against Young's Market Co.

There the story ends, as for as the terse language of the overt acts set forth in the indictment are concerned. The activities suddenly ceased, Dist. Atty. Fitts charges, soon after his office brought the investigation out into the open.

|