|

|

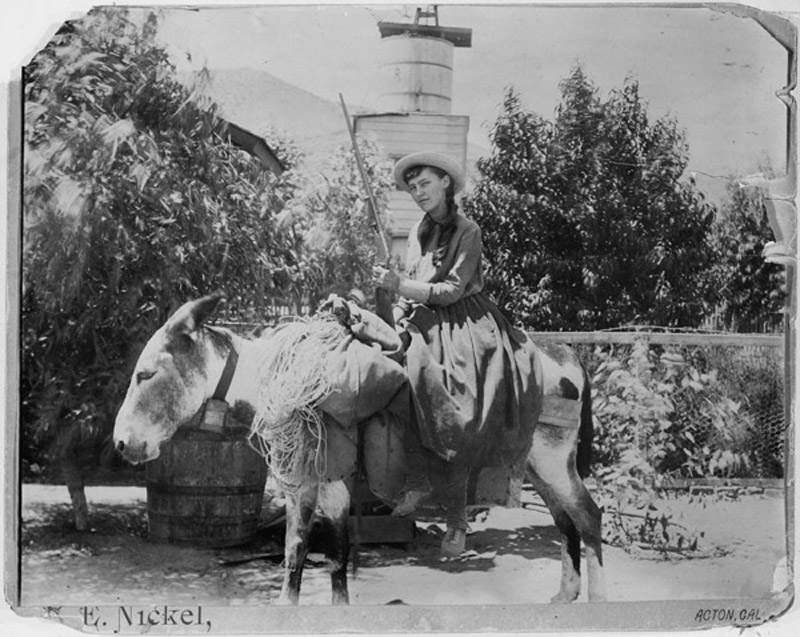

Acton, California

Lou Henry (Hoover), future wife of President Herbert Hoover, poses with a rifle on a burro for photographer Richard E. Nickel on Aug. 22, 1891, outside his store in Acton. The 17-year-old Miss Henry (b. 3-29-1874, d. 1-7-1944) spent that summer camping at nearby Mt. Gleason with her father, Charles Henry. Image in the National Archives; date of photograph from the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum. Read Lou Henry's personal recollections of her Acton summers here. About R.E. NickelSometime in late 1887 Richard E. Nickel, then 31, moved the old Soledad Post Office, as it was known by locals, from Ravenna to the general store that he built in November of that year on Acton's main street, aka Crown Valley Road. He lived above the store. Nickel officially became Acton's first postmaster Jan. 24, 1888. Nickel would become the leading citizen of Acton; he had been its second permanent resident. Nickel built the Acton Hotel, lauched the area's first water company, and in 1891 started the Santa Clarita Valley's first newspaper, the Acton Rooster. It came out on the 15th of every month for the next 22 years, keeping the town's sparse but growing population apprised of the local mining activity, events at the Acton community church, and such things.

About Lou Henry HooverSource: Herbert Hoover Presidential Library & Museum Born in Waterloo, Iowa, in 1874, the future Lou Henry Hoover learned to love the outdoors from her banker father. Speaking of her parents she wrote, "They would not want me to stay meekly at home." The day after her marriage in February 1899, the bride left for China, the first of an unending series of global journeys that would carry her to the furthest corners of civilization. Throughout her life, Lou was very much her husband's partner in everything he did, whether pursuing the history of mining, caring for Americans stranded in Europe by World War I, feeding desperate Belgium, or convincing her countrymen to voluntarily reduce their food consumption during the war in order to aid the Allies. When Prohibition became law, the man of the house emptied his cellar of the finest port in California. "I don't have to live with the American people," he told a friend. "But I do have to live with Lou." Not until Jacqueline Kennedy restored the White House in the 1960s would a First Lady lavish so much time and energy on the old house. Lou turned the second-floor West hall into a gracious room filled with bookcases and palms and transformed the shabby first floor into a showcase for American art and antiques. When the Great Depression cast a shadow over her husband's presidency, Lou hired secretaries to channel assistance to victims of hard time, after first concealing her own involvement. She also accompanied the president on his unsuccessful 1932 reelection campaign. At the end she still managed a smile for reporters. "See, we are carrying on," she said. And so she was. Spirit of AdventureAt a time when most women were expected to confine their activities to the homefront, Lou Henry Hoover took the whole world for her stage. In her youth she aspired to become a geologist, because this outdoor occupation would enable her to pursue the study of rock formations she had grown to love on hikes with her father. Turn of the century China posed an even greater challenge. During the Boxer Rebellion, Lou did not huddle in basements but nursed the wounded, scrounged up food, medicine and clothing for the injured, and even stood guard duty on barricades. When an eyewitness wrote later that this extraordinarily brave young woman actually seemed to "enjoy" the whole harrowing experience, she only reflected Lou's own feelings. As Lou told a friend, "You missed one of the opportunities of your life by not coming to China in the summer of 1900...the most interesting siege of the age." Placid by comparison, Lou's subsequent travels took her to Egypt, Burma, Australia, Japan, Russia, Germany, Belgium, France, New Zealand and Great Britain. She visited World War I battlefields and in 1921 drove her own car from California to Washington D.C. Another joy was camping trips by pack mule through the Sierra Mountains. In 1923 she took part in the founding of the National Amateur Athletic Federation. She remained active in the NAAF's Women's Division which encouraged participation by all girls and young women in the adventures of organized competition. Life of the Mind"The independent girl is truly of quite modern origin, and usually is a most bewitching little piece of humanity." So wrote Miss Lou Henry at the age of fifteen. As a truly independent girl and woman, Lou would go on to pursue a remarkably active intellectual and artistic life. She became the first woman in America to earn a geology degree, taking additional course work at the London School of Mines and authoring scholarly articles like "The Geology of the Dead Sea." Lou wrote biographical sketches of the Dowager Empress of China and as First Lady prepared an exhaustive social history of the White House. She also assembled an impressive collection of historical prints relating to the White House and early Washington, D.C. Her sophisticated musical tastes led to concerts in the East Room featuring such celebrated artists as Rosa Ponselle, Vladimir Horowitz, and Jascha Heifetz. At her behest, pianist Ignace Paderewski performed benefit concerts for the unemployed and the White House played host to Black choirs from Hampton and Tuskegee Institutes. Lou was a gifted linguist, artist, and photographer, who traded in her box Brownie for an 8 mm motion picture camera used to record family activities and her work with the Girl Scouts. On top of everything else, Mrs. Hoover was an amateur architect largely responsible for the house on San Juan Hill at Palo Alto and the presidential fishing camp built in 1929 along the Rapidan River. Gift of the HeartLike her husband, who has been called both the last of America's old fashioned presidents and the first of the new, Lou Henry Hoover was something of a transitional figure in the White House. While she shunned political speechmaking, she did become the first First Lady to be heard on the radio, where she appealed for donations for unemployment relief just as earlier she had campaigned on behalf of war-torn Belgium. Earlier still, following her 1898 graduation from Stanford, Lou joined the local Red Cross chapter and rolled bandages for soldiers in the Spanish-American War. In 1914, she organized efforts to care for U.S. tourists stranded in Europe by the outbreak of World War I. She saw to child care, food, lodging, wardrobe and even concerts and tours to divert anxious Americans from their plight. Later, she took part in promoting her husband's war work through the United States Food Administration. Her domestic "hooverizing" brought her considerable publicity, and she was not bashful about making speeches for the cause. None of these outside activities caused Lou to neglect her family. Constantly she reminded her sons of the importance of doing something worthwhile with their lives. As she put it in a 1914 letter, "The ambition to do, to accomplish irrespective of its measure in money of fame, is what should be inculcated. The desire to make the things that are, better, in a little way with what is at hand — in a big way if the opportunity comes." Lou and the Girl Scouts"I was a Scout years ago," Lou said late in life, recounting her childhood spent fishing and camping in the company of her father, "before the movement ever started." In 1917, Lou was personally recruited by Juliette Low, founder of the Girl Scouts; and for the rest of her life, Mrs. Hoover served continuously as a board member or officer. Having never had a daughter of her own, Lou once said she would not know what to do with a girl. In this as in so much else, she was being unnecessarily modest. For in truth, she adopted more than a million girls in green and brown uniforms, eager to introduce them to the outdoor world she had first encountered as a ten-year-old tomboy on the Cedar River. Throughout the 1920s she held office either as president or vice president, positions she filled on an honorary basis during and after her years in the White House. In 1929 alone she raised over half a million dollars to help realize a five-year plan of organizational development. She is also credited with facilitating the first sale of Girl Scout cookies during her second term as president. Lou Hoover was considered a highly effective spokesperson and role model for young women. Said one observer: "Mrs. Hoover is just the type of person one would expect young girls to adore. She has a charm of manner that immediately attracts one." She certainly attracted many young women to Scouting. In 1927 there were some 168,000 Girl Scouts in America. By the time of Lou's death in 1944, their ranks had swelled to 1,035,000. Camp RapidanEvery president needs a place to escape from the cares and burdens of office. For the Hoovers that place was Camp Rapidan, a rustic fishing camp located one hundred miles from Washington in Virginia's scenic Blue Ridge Mountain range and built with $120,000 of the president's own money. Those who visited the camp saw a very different man from the harried executive whose days were blighted by economic crisis. At Rapidan, Hoover could discard the formal gear of Washington for white flannels and a Panama hat. He pitched horseshoes with Charles Lindbergh and, sitting on a log with a British Prime Minister, made plans for a world disarmament conference to be held in London in 1930. Rapidan was Lou's creation as much as her husband's. She designed a four-tier stone fountain as a centerpiece, adding black-eyed Susans and larkspur to complement the lush mountain laurel. It was Lou who left explicit instructions that the President's Cabin incorporate and not destroy a majestic old hemlock tree — Lou who refused to burn live wood, coal, or oil — Lou whose scruples made for chilly nights but a warm conscience. When the Hoovers discovered that local children had no school they donated funds to build one and to hire a teacher. Most days the First Lady rode horseback, occasionally stopping in nearby Madison to patronize local rugmakers or furniture craftsman. In the evening Lou invited guests to join her as the moon rose over Fork Mountain. It was a welcome alternative to the tumult of politics and dinners for visiting royalty. Guest BookWhen someone suggested that perhaps the president would enjoy a weekend alone at Camp Rapidan, Lou brushed aside the idea. "He always wants to have people around him," she explained. He would undoubtedly turn around and come straight back to Washington if he were to arrive at the camp and find it empty of weekend guests. Among the distinguished visitors to Camp Rapidan were British Prime Minister James Ramsay-MacDonald, who protested, "I can't go to the mountains in this cutaway and striped trousers," before Hoover loaned him clothing from his own wardrobe; Charles and Ann Morrow Lindbergh, Vice President Charles Curtis, philosopher Will Durant, newspaper publishers Adolph Ochs and Eugene Meyer, industrialist Harvey Firestone, and numerous members of the Supreme Court and the Cabinet. Each visitor left his or her name in a special guest book to commemorate their time along the Rapidan. "This civilization is not going to depend upon what we do when we work so much as what we do in our time off...We go to chain theatres and movies; we watch somebody else knock a ball over the fence or kick it over the goal post. I do that and I believe in it. I do, however, insist that no other organized joy has values comparable to the outdoor experience...The joyous rush of the brook, the contemplation of the eternal flow of the stream, the stretch of forest and mountain all reduce our egotism, smooth our troubles, and shame our wickedness." LW2243: 9600dpi jpeg. |

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.