|

|

By LEON WORDEN | March 2013.

|

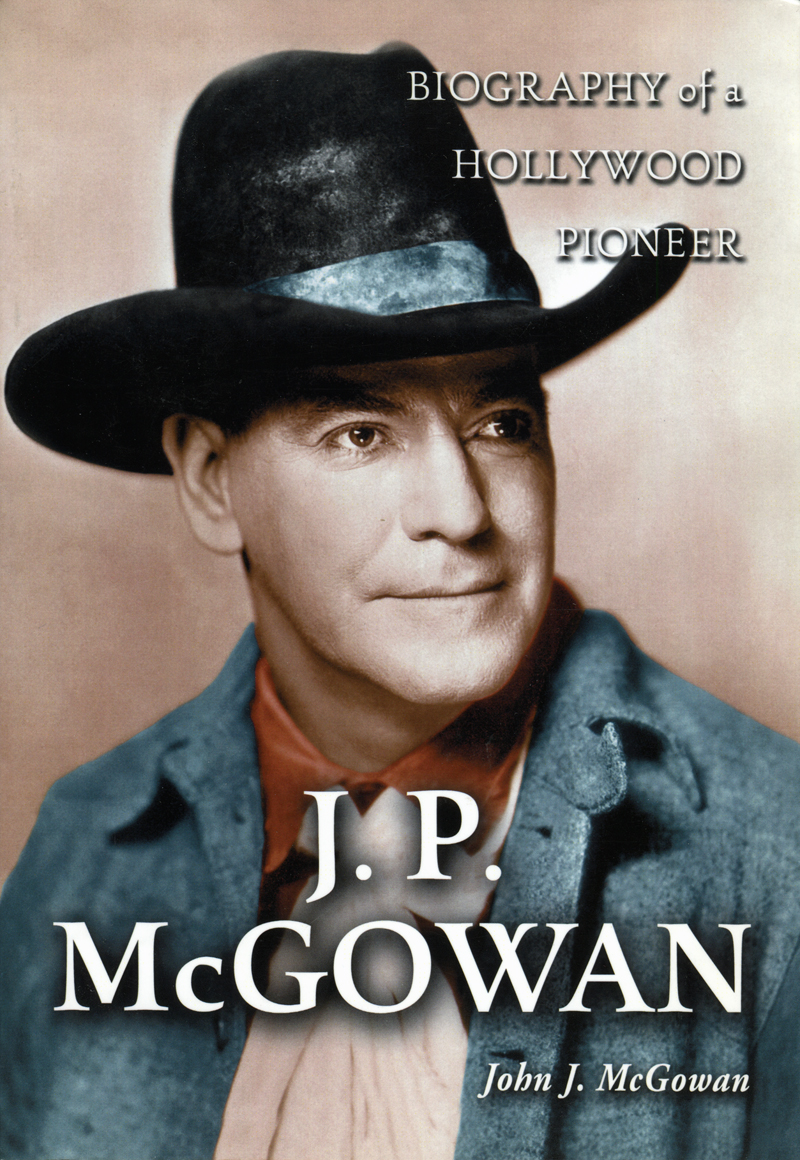

J.P. "Jack" McGowan directed, acted in, wrote and/or produced more than 600 films from 1909 to 1939. Known as "The Railroad Man" for his railroad thrillers of the 1910s and '20s, he grew up around trains and had a background in both horsemanship and showmanship that adapted perfectly to the screen. McGowan had a hand in many films shot in the Santa Clarita Valley during the 1920s and early 1930s. Of special treasure to local historians, he made "Code of the West," which shows us Newhall, and "The Last Roundup," which shows us Mentryville, both in 1929. It's difficult to judge the full extent of his (or anyone's) location work; an estimated 82 percent of all silent films are forever lost, so we can't examine their locations. Much of the following information that is otherwise unattributed comes from John J. McGowan's 2005 biography of J.P. McGowan.[1]

Terowie to Broadway John Paterson McGowan was born Feb. 24, 1880, to Scotch-Irish immigrant parents in Terowie, a rail-junction town in South Australia, which was then a British colony. Gen. Douglas MacArthur put Terowie on the map in 1942 when he was passing through and stopped on the rail platform just long enough to say he'd return to the Philippines. It was the first time he was quoted saying it. Jack's father was a laborer in a locomotive factory; Jack's 12-chapter serial of 1932, "The Hurricane Express," shot among other places in Placerita Canyon and at the Southern Pacific's Saugus Depot, is probably autobiographical in its portrayal of the relationship between father and son (a young John Wayne). Following his rudimentary, working-class schooling, Jack tried his hand at cowboying, but drought took its toll on the Australian landscape. Probably lured by the scent of diamonds and gold, Jack went to South Africa to seek his fortune and wound up getting injured in the Boer War. Delivering dispatches between British officers, his horse fell off a cliff. The horse died and Jack was hospitalized for more than a year. In 1904 Jack signed on with other Boer War vets to perform reenactments at the St. Louis World's Fair. The company paid his freight. Jack helped train the horses to play dead. Afterward he cowboyed in Texas and aided Mexican revolutionaries before heading to Minneapolis, where an uncle lived. With Jack's military experience, a traveling theater company hired him to train actors to play soldiers. He soon found himself in New York — and on the stage. Over four years he learned the craft and gained insight into scriptwriting. Of local interest, Jack joined William Faversham's troupe for the 1906 season in the Broadway production of "The Squaw Man." Playing the cattle rustler, Cash Hawkins, was William S. Hart.[2] While performing with another company on Broadway in 1909, Jack was recruited by Kalem Co., a young, innovative and prolific film company that had a no-studio policy and didn't even build any sets in its first three years.[3] Audiences responded favorably when the play broke the barriers of the stage and unleashed the "action" across authentic and diverse landscapes. Jack soon found himself traveling the world again. The Hazards of Helen

No studio meant getting out of New York for the winter. Just as D.W. Griffith at rival Biograph Co. spent his first winter in California in January 1910[4] (and directed the first known SCV-made film three months later[5]), Kalem established a base in Glendale, Calif., in 1910[6]. It was this competitive desire for outdoor shooting all year 'round that ultimately shifted the motion picture business from New York to "Hollywood" and dotted the canyons of nearby Santa Clarita with film crews. Jack's skills as a horseman helped him establish himself as an actor in a time before stunt doubles. He earned his first screen credit in 1910 when a character actor took ill, and landed his first leading role in 1911's "The Colleen Bawn," shot in Ireland. Earlier that year, Kalem had sent the first U.S. film troupe overseas. At Kalem, Jack was mentored by some of the best artists who'd also dared to make the transition from stage to film[7], which most theatrical players still derided.[8] On Dec. 1, 1912, Jack was put in charge of Kalem's railroad productions. That same month, most of the top talent walked out when Kalem decided not to give any screen credits on its biggest picture, a 6-reeler that had been shot in Egypt and Palestine about the life of Christ. Jack stayed, and having learned enough of his former colleagues' tricks of the trade, settled into the director's chair[9]. One needed to be a utility player, to borrow a term from baseball, skilled at a variety of positions, in the earliest days of motion pictures. But the survivors in the quickly growing industry would need a specialization, and railroad melodramas became Jack's. "(T)he single main issue which defines his individual contribution to the motion picture industry, whether in terms of production numbers or the development of a signature directing style, is his body of work as a director and actor in the genre of the railroad drama," Jack's biographer writes.[10] Jack went West (for good) in mid-1913 as head of Kalem's Hollywood production unit[11]. Interspersed with other dramatic themes, he focused on producing and directing railroad thrillers, usually starring the daredevil actress Helen Holmes (1892-1950), whom Jack married.[12]

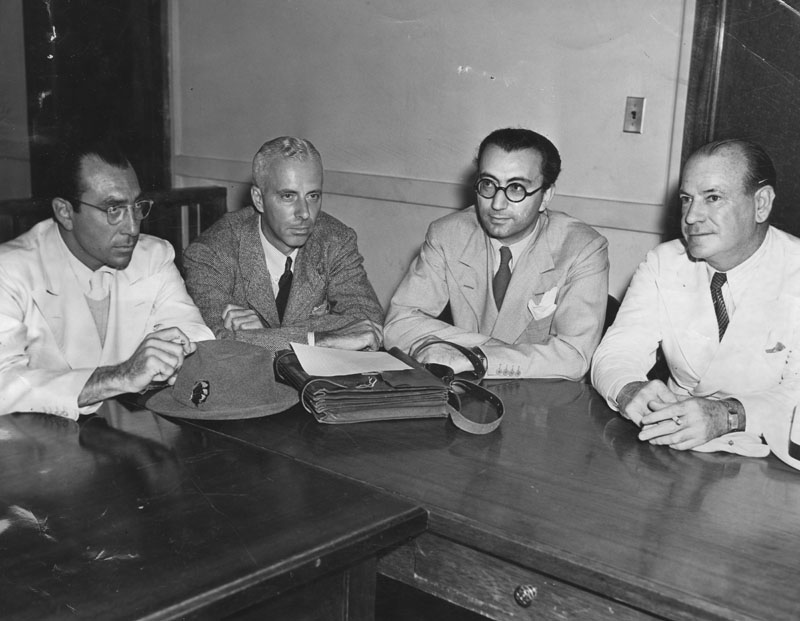

Jack and Helen's action-packed "The Hazards of Helen" railroad series would go on for a near-record 119 episodes[13], but they left Kalem in mid-1915 after about 50 episodes[14] for reasons that are forgotten. It may have been a matter of creative license; it's known they wanted to make a railroad serial, rather than a series.[15] Jack did some work for Lasky and both did some unsatisfying work for Laemmle[16] before they hooked up with the executives with Mutual, a distribution company, which formed a new production company for them, Signal Film Corp. Jack and Helen were technically employees but they had complete production control and a bigger budget. And now, Jack was writing many of the scenarios himself.[17] Working at a frenetic pace, Jack and Helen churned out four railroad serials in the next two years. Poverty Row Everything came to a crashing halt in early 1918 with the collapse of Mutual. Jack and Helen separated.[18] With a reputation as an action-adventure specialist, Jack spent the next few years directing and often acting in serials and five-reelers for Universal and smaller studios. Jack and Helen reunited in 1921 and made some features together in Florida in 1922-23. They returned to California in 1924 to make five-reel Westerns and tried to revive their "Hazards" success with more railroad pictures. It was not to last. Helen ran off and married a movie stuntman in 1926 and retired from the screen.[19] Jack was devastated. Paraphrasing another writer, Jack's biographer offers the theory that "the loss of Helen resulted in Jack taking cheap jobs on Poverty Row rather than realizing his full potential which could ... have made him one of the great directors."[20] He was also slow to adapt to sound. Jack needed action in every frame. Early sound equipment made cameras heavier and less nimble, and setting up for sound hindered mobility. But an aversion to sound limited his films' audience appeal and kept them out of the largest picture houses, which were refurbishing to accommodate the new technology. After Helen left, Jack directed Tarzan pictures shot in Southern California for Robertson-Cole Pictures Corp., a predecessor of RKO, and in 1928 he directed what would be his last silent serial, "The Chinatown Mystery," written by John Ford's elder brother Francis Ford and produced by Trem Carr's Syndicate Pictures Corp. Jack directed several silent features that year for Carr, whose Poverty Row production company was renting a Hollywood studio and often shooting action scenes in Placerita Canyon. By 1929, Jack was re-energized, thanks in no small measure to a new professional relationship with yet another creative and talented woman, writer Sally Winters. Together they churned out an astounding 30 one-hour pictures from September 1928 to October 1930, including 14 five-reelers released by Syndicate from July to December 1929. Among these were some obscure gems for Santa Clarita historians: "The Last Roundup," released in July, and "Code of the West," released in November. The former gives us unique views of the Mentryville oil town in Pico Canyon, while the latter shows us Newhall. Both were silent, although "The Last Roundup," intially conceived as totally silent, marked the first time Jack added a music track to a production.[21] Both films starred Tom Custer, who appeared in 13 McGowan-Winters features. Bob Steele played in another eight and Tom Tyler in seven. Most small towns in America have still photographs to capture their communal memories; thanks to Trem Carr and Jack McGowan, we've also got moving pictures. Sadly, Jack couldn't forsee that his success would spell personal misfortune. Hard Times Just in time for the stock market to crash in October, Jack invested his own money in 1929 and formed J.P. McGowan Productions, with a distribution agreement through Syndicate. He lost his shirt and "never regained his momentum," his biographer writes.[22] Before the end of 1930, J.P. McGowan Productions was kaput. Jack continued to direct for the Povery Row producers who regularly used Placerita Canyon for location work: Carr (Syndicate, Mongram, early Republic); W. Ray Johnston (Rayart, Syndicate, Monogram); Nat Levine (Mascot); and the Machiavellian Herbert J. Yates, who during the depths of the Great Depression leveraged the debts owed by the Poverty Row producers to his film processing company, Consolidated Film Laboratories, to absorb the smaller production companies (including Carr and Johnston's first Monogram) into his Republic Pictures Corp., the new king of the row. In March 1933 Yates even sued Jack to collect a debt of $245.29 he owed to Consolidated. It added insult to injury. Jack's directing work had slowed considerably, but friends frequently cast him as a heavy in movies starring the likes of Randolph Scott, Buck Jones, William Boyd (Hopalong Cassidy) and Gene Autry. He concluded his directoral career with "Where the West Begins" for Monogram (shot in Kern County and released in February 1938) and made his last screen appearance as an extra in John Ford's "Stagecoach" (1939). While he never made a fortune in pictures, except for the scary Depression years he was usually comfortable. In December 1940, Jack and his second wife, Kaye (formerly Katherine Sevart[23]), bought a modest house for $3,000 at 1229 N. Olive Drive in Los Angeles (now West Hollywood), not far from William S. Hart's house.[24] By this time Jack had other priorities. The Screen Directors Guild (now the Directors Guild of America) had formed in 1936 and was still fighting for recognition as a negotiating body when Jack signed on as executive secretary in 1938 under its first president, King Vidor. The studio bosses, who could gang up to blackball a pesky director, wanted to kill the unions.[25] Off Camera

Under Frank Capra's leadership the following year, the directors wanted a 60-hour week, overtime for Sundays and holidays, minimum pay rates for second-unit directors, creative rights, and arbitration to resolve disputes over screen credits. In February 1939, more than 250 directors met in Hollywood and voted unanimously to boycott the Academy Awards unless their demands were met. That did the trick. The major studios capitulated on almost all points. Jack's job was to negotiate with the Poverty Row producers. Jack found an odd ally in his old nemesis, Herbert Yates, who uncharacteristically (or shrewdly?) convinced Republic and the other Poverty Row studios to fall in line. Jack held his executive position with the guild for a record-setting 12 years and in 1951 was only the eighth person to receive an honorary life membership, which was bestowed for "outstanding creative achivement, or contribution to the Guild, or the profession of Directing." During this period, Jack suffered from chronic heart disease. On Wednesday night, March 26, 1952, he suffered a heart attack and died in his sleep at his home. He was 72. His ashes were interred in a niche at Forest Lawn. Kaye's ashes joined them 10 years later, along with those of her father, Samuel Sevart. The first Australian to establish a full-time film career in Hollywood, Jack McGowan never made the big time. He came from working-class stock and thrilled working-class audiences with films that made heroes of working-class railroad men, courageous women and honest cowboys. He spent his sunset years standing up to studio bosses, fighting for fellow filmmakers' rights. Today, but for the biennial Days of Rail and Screen in tiny Terowie, this film pioneer is largely forgotten, and that's a shame. When you consider the now-historic moving pictures of our canyons and towns that wouldn't exist without him, we're lucky he chose us as his canvas. 1. McGowan, John J. "J.P. McGowan: Biography of a Hollywood Pioneer." North Carolina and London: McFarland & Co., 2005. Author John J. McGowan is an Australian relative of J.P. McGowan but not a direct descendant. 2. Koszarskim, Diane Kaiser. "The Complete Films of William S. Hart: A Pictorial Record." New York: Dover Publications, 1980, pg. xi. Hart's own calling to the screen would come a full five years after McGowan's. 3. Kalem Co. was founded in 1907 by George Kleine, Samuel Long and Frank Marion — the K-L-M of "Kalem." No 2 behind Biograph, Kalem churned out about 300 one- and two-reelers per year until 1917. (One reel was usually 11 or 12 minutes.) Before D.W. Griffith started making epics for Biograph, filmmakers didn't think audiences had the patience for anything longer than about 20 minutes. See Iris Barry's "D.W. Griffith: American Film Master" (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1940). 4. Barry, op. cit. 5. Griffith's "Ramona," a one-reeler starring Mary Pickford, was shot April 1 and 2, 1910, at Rancho Camulos and Piru. It was released May 23, 1910. 6. Kalem crews had already been spending winters in Jacksonville, Fla., prior to establishing a presence in Glendale. 7. Early mentors included the hard-driving director, Sidney Olcott (1873-1949), and scenario writer (scenarist) Gene Gauntier (1891-1966). Gauntier was the first of three women during McGowan's career who would have a profound impact on his work. 8. Just as "video killed the radio star," film also killed the theatrical touring business. According to author Philip C. Lewis in "Trouping: How the Show Came to Town" (Harper & Row 1973), there were 339 companies on tour in 1900; by 1910 they numbered just 236 and by 1935 only 22 were left. The attraction, according to Lewis, was the money to be made in film. "The real jolt," Lewis writes, "was the news about Bill Hart. W.S. Hart, who played in 'The Squaw Man,' 'The Christian' and so on — $2,225,000 from nine films in only two years! You could play one-nighters until the end of your life and then send your corpse on tour and you still wouldn't get that kind of dough. And Chaplin! Even if you believed only half of what they said, he was still getting more than the President of the United States." 9. He had actually directed once before, a one-reeler called "A Prisoner of Mexico," released Oct. 23, 1911. 10. John J. McGowan, op. cit, pp. 57-58. 11. Kalem first used property in Verdugo Canyon (Glendale) in 1910 and established a studio in Santa Monica in 1911. In 1913, Jack apparently started out at the Glendale location, but in October 1913, Kalem took over the Essanay Studios property at 1425 Fleming St., Hollywood. (An acronym like Kalem, Essanay was S-and-A & #151; George K. Spoor and Gilbert M. Anderson.) 12. Holmes, whom Jack recruited from Mack Sennett's Keystone Studios, was the second influential woman in his life. (See footnote 7.) They probably married in 1914; they adopted a daughter, Dorothy, in 1915. The marriage lasted on and off until 1926. (Ibid., pp. 61 and 65.) 13. It was surpassed by the "Pearl White Crystal Comedies" series at 135 episodes. Kalem produced "The Hazards of Helen" through early 1917, the year the company folded (ibid., pg. 75.) 14. Kalem replaced Helen Holmes with Helen Gibson, wife of actor Hoot Gibson (ibid. pg. 73.) The two Helens became close friends; Gibson was at Holmes' bedside when the latter died July 8, 1950, from pulmonary tuberculosis (pg. 99). 15. In a serial, the story continues from week to week. In a series, each episode is a self-contained story with a beginning and end. 16. Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company; Carl Laemmle was head of Universal Motion Picture Manufacturing Company, aka Universal. 17. Silents, especially shorts, didn't usually have full-blown screenplays; they worked off of cursory outlines called scenarios. 18. Jack's biographer suggests that the hectic work schedule of the past two years resulted in "physical and emotional burnout," and that Jack was a suspicious and jealous husband who was distraught when the marriage failed. 19. Lloyd Saunders. The couple moved to Saunders' cattle ranch in Sonora, Tuolumne County, which went bust in the Great Depression. Helen attempted a comeback to the screen in 1936 but secured only minor roles over the next several years. 20. The source of the quotation is Ford Beebe, a colleague of McGowan at Signal Film Corp., as cited in the movie nostalgia tabloid "Classic Images" ("Ford Beebe recalls Helen Holmes and J.P. McGowan. As told to Eldon K. Everett," by Eldon K. Everett, July 1982 and August 1982). "Poverty Row" refers to the smaller, low-budget and often short-lived production companies of the 1920s-50s, many of which rented studio space at or near Hollywood's Gower Gulch (Gower Street and Sunset Boulvard). 21. He didn't always add music after this; as late as July 1930, "Oklahoma Sheriff" with Bob Steele was totally silent. 22. Op. cit, pg. 106. 23. Twelve years Jack's younger, Sevart was a public school teacher. 24. Located amid apartment buildings, the house still stands as of 2013. It's just a couple of blocks from William S. Hart's house on DeLongpre. Hart still owned, but no longer lived in, his DeLongpre house when McGowan moved into the neighborhood. 25. A predecessor of the Screen Actors Guild formed in 1925; Louis B. Mayer of MGM formed the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in January 1927 to mediate labor disputes. SAG organized in 1933.

|

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.