|

|

Antelope Valley Indian Museum State Park, Lancaster

Click image to enlarge

December 28, 2013 — Piute Butte at Antelope Valley Indian Museum State Historic Park, Lancaster. Close to sunset.

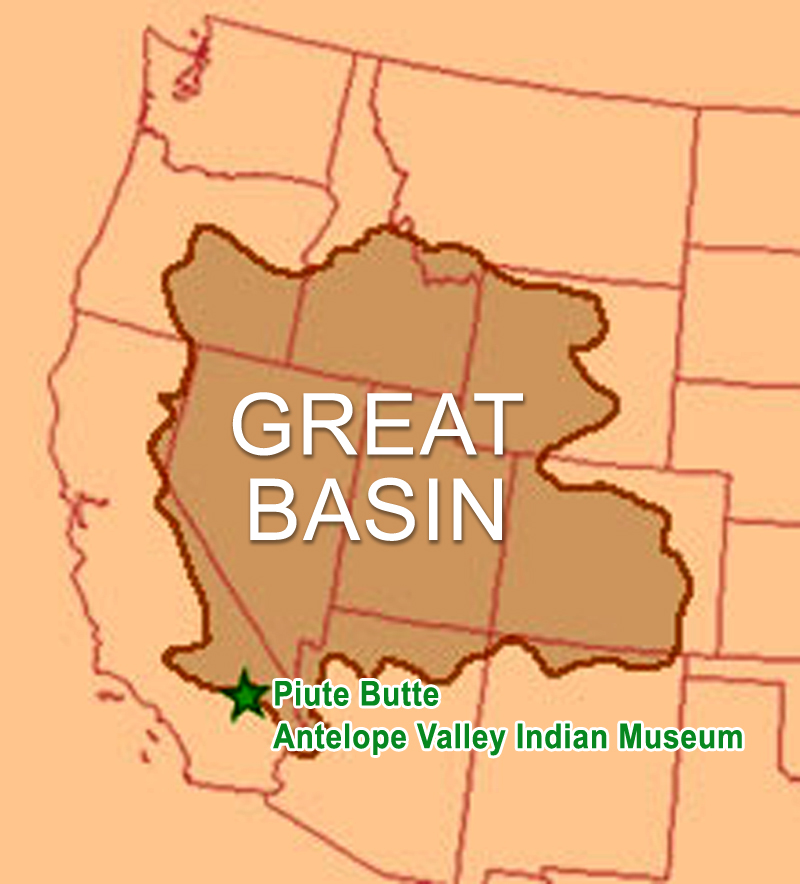

"Piute Butte" is the modern name of a granite outcropping located on the grounds of the Antelope Valley Indian Museum State Historic Park in eastern Lancaster, north of Lake Los Angeles. In a larger context it sits at the southwestern edge of the Great Basin region, which covers 400,000 square miles from the Sierra Nevadas to the Rocky Mountains. It has seen many peoples live and pass through the region over the last 12,000 to 13,000 years including, in more recent times (the past 2,000 years or so), the Kawaiisu, Serrano, Kitanemuk and Tataviam.

"By 2000," writes Edra Moore, the state park's first director, "the body of evidence that had been accumulating seemed to support the hypothesis that the upper rocky slopes and crest of the butte may have been reserved for ritual and ceremonial purposes during prehistoric times." Current Native American residents "have long perceived the butte as having spiritual significance," she writes, and in 2003, Piute Butte was added to the California Native American Heritage Commission's Register of Sacred Sites. Further study concluded that the "petroglyphs, pictographs, cupules, and rocks culturally enhanced to resemble symbols associated with fertility, in combination with natural outcrops, boulders and monoliths resembling human or animal shapes, represent ... a general religious pattern found throughout (pre-contact) southern California." Similarities were found between the butte's features and other examples in Southern California and the Great Basin that are associated with cosmological concerns such as fertility, weather monitoring, seasonal renewal or other astronomical associations. Radiocarbon dating on pigment samples yielded a calibrated calendar age range of between 150 B.C. and A.D. 400. Piute Butte can be observed at a considerable distance from a park trail. The butte itself is off-limits to the public.

Throw the kids in the car and take a weekend excursion to far-eastern Lancaster where you'll find the Antelope Valley Indian Museum, a state park facility set against a stunning rock formation. Dating to the early 1930s, it's an eclectic folk art-style building that houses 8,000 Native American artifacts, including many from cultures in and around the Santa Clarita and Antelope valleys. The Antelope Valley Indian Museum (AVIM), now a state park facility, began as a private home built on land homesteaded in 1928 by Howard Arden Lex Edwards (1884-1953). Edwards was a painter and theater set designer who taught art and set design at L.A.'s Lincoln High School from 1924 to 1945. In the late 1920s-early 1930s, Edwards lived in Eagle Rock and spent weekends building a folk art chalet (some consider it Arts and Crafts) below the south-facing slope of Piute Butte, the name he gave to a distinctive granitic formation in northeastern Los Angeles County that had served as a sacred native American fertility site. The butte itself is off-limits to the public today, due to its cultural sensitivity. Edwards was an amateur collector who amassed a large volume of American Indian cultural materials, some of which he found on the property but most of which he purchased from dealers and what would today be considered grave robbers. (The Smithsonian Institution and museums around the world are filled with human remains and relics recovered by archaeologists from the 1870s onward, from countless thousands of burial and village sites across Southern California. Artifacts at AVIM have been handled in accordance with the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.) The area of Piute Butte and nearby Lake Los Angeles (once an actual lake) was a major four-directional prehistoric trading crossroads, not unlike Vasquez Rocks in Agua Dulce. Edwards' collection included not only artifacts made by members of the various local Shohonean linguistic groups — the Kawaiisu people of the immediate vicinity, Kitanemuks and Serranos of the Antelope Valley, and Tataviam people of the Santa Clarita and southern Antelope valleys — but also artifacts representative of implements that would have reached them along the trade routes (i.e., "imports"). Edwards collected heavily from the Channel Islands (Chumash culture) as well as the Owens Valley (Southern Paiute) and the American Southwest (Pueblo). Edwards named his house Yato Kya (Ranch of the Sun), from the Zuni word for sun — Ya'dok'ya. He built it around and into a rock outcropping, leaving the boulders in place and incorporating them into the walls (or vice-versa). He used Joshua tree wood as a decorative feature in interior walls and ceilings, which he painted in vivid Southwestern hues — in stark contrast to the subdued tones that were common for the area. For the ceiling of the living room, Edwards drew stylized Kachina motifs on theatrical set board (low-grade plywood) and had the students in his adult art education classes paint them. He filled the structure with natural light, setting windows high on walls to illuminate the ceiling, and in natural gaps in the rocks to illuminate grottoes. Edwards filled one room (now the California Hall) with artifacts and dioramas and opened it to the public in 1932 as the Antelope Valley Indian Research Museum. He held annual pageants to promote the venue. Edwards mounted and labeled his artifacts on boards, grouping them together by his perception of their use, rather than by culture. Often he identified things correctly, but sometimes he made up stories about them, based on characters in a book he was writing. (Santa Clarita Valley historians might draw a parallel to Robert Callahan's Mission Village in L.A. or his Old West Indian Museum in Agua Dulce.) Today, AVIM is a showcase as much for the artifacts as it is for the changing ways they've been interpreted and handled over the years. Edwards sold the place in 1939 to Grace Wilcox Oliver (then married to Ralph G. Fear, owner of a Hollywood camera dolly company). Oliver was an anthropology and archaeology student who had a somewhat more sophisticated perception of native American lifeways. She also had a sizable collection of her own. She made some badly needed structural improvements; built new cottages (which Edwards painted for her in 1944 and 1945); and installed display cases. She had health problems that caused her to sell the property in 1948 but she recovered and bought it back in 1952. In between it was used as a dude ranch (guest ranch). Oliver hired Edwards — who at this time was cataloguing artifacts for the Southwest Indian Museum — and she recruited a UCLA grad student named Charles Rozaire to reinterpret the collection. Rozaire would go on to become a leading Southern California archaeologist. Rozaire rearranged the artifacts by culture, then by use, and organized them to show how the various cultures changed over time. Oliver filled most of the building with artifacts — it was no longer primarily a dwelling — and designated different rooms for major subjects, such as Antelope Valley, Great Basin, California and Southwestern. Among her new acquisitions was an important local grouping of 2,000 artifacts from a dig at Barrel Springs near Palmdale, which she got on loan from the University of Southern California in the mid-1950s. When USC closed its Anthropology Department in 1962, some of the artifacts were transferred to the L.A. County Museum of Natural History but some remained and are still on exhibit at AVIM. Oliver kept the museum open for most of the next two decades, depending on her health, until the mid-1970s when she decided to sell the property and disburse its contents to museums. But certain Antelope Valley residents had other ideas. Activists, led by one of Oliver's neighbors, Beryl Amspoker, lobbied the state to take it over. Against long odds and bureaucratic opposition, in 1978 the Legislature passed and Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill by Assemblyman Larry Chimbole, D-Palmdale, authorizing the purchase of the land and the building. The purchase was made in 1979 and Oliver donated the contents, but without funding for permanent staffing or exhibits, the state relied on volunteers to give tours. The Friends of the Antelope Valley Indian Museum (FAVIM) formed in 1982 to serve as docents and raise money for projects and improvements. (Today, 2013, fundraising by FAVIM is responsible for keeping the museum off of the State Parks closure list.) In the late 1980s, State Parks designated the facility a Regional Indian Museum for Great Basin cultures (east and southeast of the Sierra Nevada mountains). In 1989 the state hired its first permanent employee for the museum, Edra Moore, a grad student at UC Davis, as curator. Moore immediately enlisted the aid of some leading experts to help her reinterpret the materials yet again — people like David Earle, an authority on the archaeology and ethnology of the Mojave Desert region. Moore took a "culture process" approach to the exhibits, showing how people interact with and adapt to their environment — as seen in her emphasis on trade routes in the museum's Antelope Valley section. It provided context for many of Edwards' and Oliver's "other-area" materials by showing that they would have been traded and used locally. Moore was also receptive to the advice of local native American leaders such as Charlie Cooke, who alerted her to the property's spiritual significance and helped support her successful petition for federal recognition as a sacred site. On Feb. 26, 1987, the property was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Beginning in 1992, Moore spent 15 years cataloguing all 8,000 artifacts and bringing the collection into conformity with the 1990 NAGPRA. In 2002 the state redesignated the site the Antelope Valley Indian Museum State Historic Park. It has served as a repository for additional materials including the Irvin S. Cobb collection of pottery from New Mexico Pueblos of Santa Clara, Acoma and Maricopa, and Hopi pieces from Arizona; and the Betty Goshay collection of 30 artifacts donated in 1988, including Hopi Kachinas, Acoma and Zuni pottery, and Hopi and Papago basketry. AVIM also houses other artifacts found during archeological investigations and road construction projects in the Antelope Valley. The museum can be visited on weekends for a small admission fee (12 and under free). It is located 17 miles east of SR-14 at 15701 East Ave. M, Lancaster CA 93535. To get there, exit SR-14 at Avenue K and go east; turn right (south) onto 150th Street East for two miles; turn left onto Avenue M and proceed 1 mile to the museum. — Leon Worden 2013 Sources: ___ "Antelope Valley Indian Museum State Historic Park." Brochure, Calfornia State Parks, 2005. ___ "Antelope Valley Indian Museum SHP #579." California Indian Heritage Center, State of California Department of Parks and Recreation, 2003. ___ "Piute Butte: A Preservation Planning Study" by Edra Moore. Society for California Archaeology: SCA Proceedings, Vol. 23, 2009. Friends of the Antelope Valley Indian Museum. "Guide to the Antelope Valley Indian Museum State Historic Park." Lancaster: California State Parks 2010. Gordon, Mary Louise Contini. "Tiq Slo'w: The Making of a Modern Day Chief." Tucson: Mary Louise Contini Gordon, 2013:235-239.

LW2555i: 19200 dpi jpeg from digital image by Leon Worden. |

Building x7

Piute Butte x2

Female Fertility Feature x4

Piute Butte: A Preservation Planning Study (Moore 2009) Lovejoy Springs & Western Mojave Desert Prehistory

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.