|

|

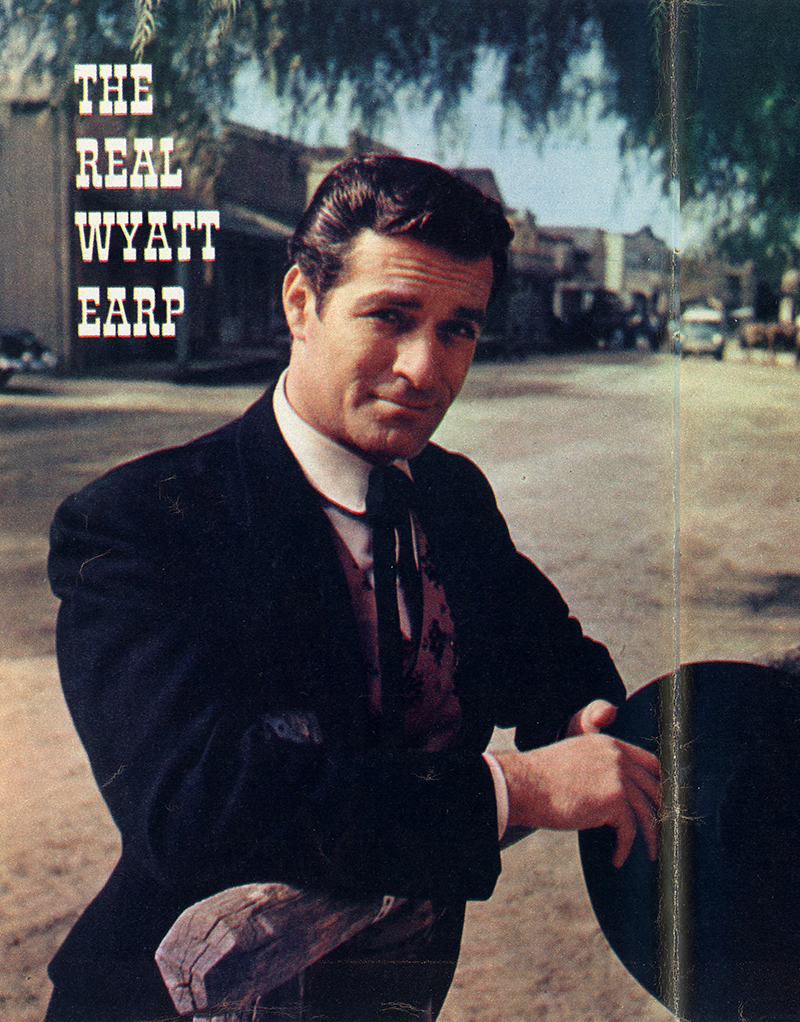

The Real Wyatt Earp.

Hugh O'Brian may be a tough hombre on TV, but he's no match for the original marshal.

| May 2, 1959.

|

Webmaster's note: Hugh O'Brian starred as the title character in "The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp," a 6-season (226-episode) dramatic series whose "home studio" was Gene Autry's Melody Ranch in Placerita Canyon. The show aired on ABC Tuesdays from September 6, 1955, to June 27, 1961.

Television's Wyatt Earp, as played by actor Hugh O'Brian, is frequently accused of bearing little or no resemblance to the real Wyatt Earp, the celebrated gunfighter, town tamer and marshal. The dissimilarity is not so marked as some skeptics say. To be sure, the television Earp's face is barren — in notable contrast to the real Earp's fierce mustache — and certain Vine Street modifications have been made in the Stetson-type hat, high-button coat and white shirt that were standard attire in Marshal Earp's day. But O'Brian paints a fair picture. There is even some physical resemblance to the "square-jawed, rail-thin but strong" marshal. The most valid complaint is that he does not play Earp heroically enough. The TV Earp pales before the exploits of the stern-visaged lawman. O'Brian's problem is to play down the part so modern audiences will believe it. The real Earp was a mighty tough customer, according to Stuart N. Lake, who, after years of intensive research, wrote the biography on which the ABC series is based. His favorite disciplinary method was known as "buffaloing." This meant that he laid the 12-inch barrel of his Buntline Special across the miscreant's skull and hauled him off unconscious to jail. Being a humane man as well as a tough one, Earp seldom shot to kill if he could help it. In fact, he would not shoot at all unless forced. It was not uncommon for him to buffalo 20 or 30 obstreperous cowboys in a single Saturday night. Buffaloing was not only painful but insulting. It implied that the gun toter was not formidable enough to rate having continued a gun pulled on him. Buffaloing was always done with the barrel, never the butt. The man foolish enough to try the butt would be dead the instant he reversed the gun muzzle. Killers, of course, were a different matter. At one time, organized outlaws made a standing offer of $1,000 to any gunfighter who knocked off Earp. The real Wyatt had to deal not only with these mercenaries but with the young hotheads hoping to establish reputations by outgunning Earp. Earp's speed on the draw was almost other-worldly. As Bat Masterson told Lake: "In a day when almost every man had, as a matter of course, the ability to get a six-gun into action with a rapidity that a later generation simply will not credit, Wyatt's speed was considered phenomenal by those who were marvels at the same feat.'' Wyatt also was a superb tactician and psychologist. He knew how to tame the rebellious mob by singling out its moving force. Once the leader had been maneuvered into giving ground, the whole movement collapsed. According to Lake, there is no substantiated instance of Earp ever having "cited a hurdle" (backed down in a fight because of too-great odds). The Battle of O.K. Corral was e classic example. When Wyatt accepted the invitation of the Clanton gang for a showdown in that dusty Tombstone (Ariz.) corral in 1881, says Lake, the cards were stacked against him. Ike and Billy Clanton, the deadly McLowery brothers and trigger-happy young Billy Claiborne would be waiting in ambush. Wyatt had only his two brothers, Virgil and Morgan (lesser guns), and the tubercular dentist, gambler and gunfighter Doc Holliday, who came along strictly out of loyalty to Wyatt. The battle was over in 30 seconds. Just 34 shots had been fired. Ike Clanton was begging for his life, Claiborne had fled, and Billy Clanton and the McLowerys lay lifeless. The Battle of O.K. Corral has become the most celebrated fight in frontier history. In one variation or another, it constituted the climax of dozens of movies and television shows. Occasionally, it even may be seen on "The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp." Why do even the best of the TV Westerns tend to seem so synthetic? The main trouble is that, however much the heroes may resemble their real-life counterparts, the backgrounds in which they play out their parts do not resemble the real settings. If one were to show Dodge City — or Tombstone or Wichita — as it was, one might very well blast the family audience right mt of the living room. In the brawling era of the cowtown, with its roistering throngs of trail herders, buffalo hunters, cattle barons, gandy dancers, mule skinners, gamblers and gunfighters, its denizens did not play the game by polite rules. The liquor flowed freely and had the usual effect, intensified by long, lonely vigils on the cattle trail or railhead. Hurrahing (shooting up) the town was a natural by-product, and Dodge City had to outlaw the riding of horses into public buildings. Outlawry, before Earp, was so well organized that lawmen often found easier simply to sell out to the transgressors. A few years later, when Earp arrived in Tombstone, he found Old Man Clanton ran everything in Arizona (including the sheriff) and terrorized the whole Southwest. This is not to say there was not a good element. There was even a church in Dodge, which Wyatt himself occasionally attended. The reform mayor, Dog Kelley, backed Earp, and between them they made life possible for the law-abiding citizens. Yet Earp, for all his sterling qualities, was a human being. After the Battle of O.K. Corral, the remnants of the Clanton gang descended on Tombstone and pumped shotguns full of buckshot into Virgil Earp. Later. they killed Morgan Earp. Wyatt hit the vengeance trail. Relentlessly he chased the gang all over the Southwest, gunning them down one by one, finally trailing Curly Bill Brocius (the leader) to Iron Springs and shooting him dead. Wyatt left Arizona in the 1880s, joined the Alaska gold rush, did some silver prospecting, and died peacefully in 1929, at 80, in Los Angeles. "Wyatt was no saint," Stuart Lake says. "He was a man — and, all things considered, one of probity, integrity and inherent human decency." O'Brian agrees that Wyatt was "a lusty character, too lusty for TV." Then he adds, "He had to have faults to be human. And I try to play him that way — relaxed until he loses his temper, then all steel springs; capable of occasional errors in judgment, but humble about them." O'Brian and writer Frederick Hazlitt Brennan have done what every writer of TV Westerns has done — knocked a few rough corners off the marshal so he will be acceptable in the living room. Thus TV's Wyatt Earp becomes a clever imitation — which is a pity only when you consider the merits of the real man.

LW3274: TV Guide clipping purchased 2018 by Leon Worden. Download individual pages here.

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.