|

|

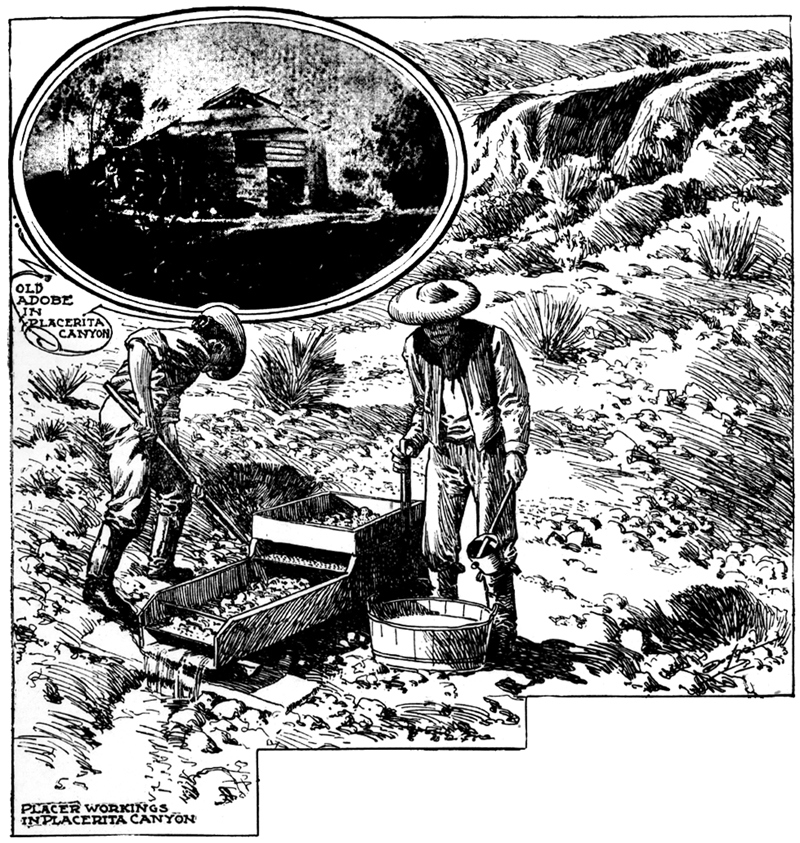

Placerita Canyon

Romantic Spot That Has Yielded Much Treasure, and Where Some History Has Been Made

By Eleanor Quigley

Los Angeles Herald Illustrated Magazine | February 9, 1902

|

It was over this trail the good padres, when the rains were plentiful, led the peaceful inhabitants of the mission, to the little placer gold mines which they had discovered in the Placerita, the Orioso and Oro Fino canyons, and there deftly taught the tractable red man how to obtain the precious metal. At the foot of the gorge the trail ended in a plateau, shaded by mountain oaks, watered in summer by a tiny crystal brook, that brightened to silvery sheen, then darkened to sapphire blue, as it flowed through sunshine and shadow, down its sandy bed under the overhanging branches of the great trees. In winter the brook became the resurrected river. Under the oaks, on the green carpet of semi-tropic growth, the Indian miners made their campfires and spread their blankets; and from then until now men have camped there and worked the little pacers, seeking the yellow talisman that brings joy to the saddened heart; that lightens toil and, like charity, covers a multitude of sins. That the padres took from these placers gold in considerable quantities there is no doubt; for, notwithstanding the continued working of the mines up to the present time, there is an occasional strike in a "draw," a side gulch, or a "pot-hole" in the main channel, overlooked by the early miners, that pays well for the working. After the passing of the mission government, when the seasons were favorable, Indians continued to work the little placers. Some of them had become skilled miners, following the broken channels of pay dirt by tunneling, sinking shafts and driving in the higher levels. As late as the early sixties the Indians, in quite large numbers, came from the borders of Lower California to work those mines. In 1871 a white miner, who was running a tunnel, struck into a network of old workings, in which he found rusted mining tools. In the bata were nuggets of gold, amounting to thirty dollars. We can but surmise the fate of the owner. No trace of his remains was found. Following the Indian miners came the Chinamen, who, with had sluice, rocker, and pan, persistently washed the gravel all over again. When the organization of the San Fernando mining district was accomplished, the alien miners were bared out, and the little placers were claimed by white men, who, in a few instances, succeeded in mining the yellow dust in paying quantities. With the passing of the Indian, the Chinese and the early white miner, there was left to the new order of things a legacy of legends, traditions — stories of ledges of rich ore that the padres had worked, and, before they went away, had covered up all traces of; and of old channels under foothills or mountain edge, where the gravel was so rich that a pan would yield a dollar in gold. Prospectors have spent much time in searching for the legendary mines. But if the mines exist their secret is still hidden under the growth of chapparal [sic], the tangled matting of which still screens the whole northern slope of the mountains. Over two decades ago a man who had been a sea captain, lumberman, miner and rancher, and with whom Dame Fortune had coquetted even more than is the custom of the fickle jade, pitched his tent on the plateau, at the head of the Placerita canyon. The great oaks of the padres' time had been cut away, a new generation of trees had taken their places. The channel of the brook had been dug over, and its water turned into ditches along the mountain sides in the canyon. Every gravel bar, point and "draw" had been turned over to bedrock. The bowlders [sic] and gravel, systematically piled in heaps, had, in many places, been again buries by the debris of the winter floods. The "captain" knew something of the history of the canyon, and had heard the legends. But he was most impressed by the incomparable climate and beautiful surroundings, that appealed to his love of nature. He, in first prospecting for gold, found sufficient to induce him to remain. He bought a number of claims, for which he paid the last remnant of his fortune. Being a bachelor, he moved into an adobe hut on his new estate, and went to work with pick and shovel. But fortune has not smiled on him, during all these years of toil and hardships that would appal [sic] and ordinary man. During the last quarter of a century $100,000 has been expended in futile efforts to mine the Placerita with machinery. In 1891 a company spent $30,000. Immediately following this failure another company installed an expensive plant, in which both steam and electricity were to play important parts. These are but two notable instances. Men with thousands of dollars, and others with a few hundred, have alike fallen victims to attractive but visionary schemes for mining by processes requiring more water than proved to be available. Owing to the collapse of the great real estate boom in Southern California about 1888, many men were left stranded in Los Angeles and vicinity. Some came, as a last resort, to Placerita and adjoining canyons — thinking to tide over the stress until times were better. Some of the claim owners allowed men to mine free. Others took a small royalty. Those tyro miners [tyro means novice — Ed.] who brought their families lived in hastily constructed "shacks," or in tents; women and children helping to wash the auriferous gravel, securing for their labor sufficient to feed them. In the language of the miner, they made "grub." Grub mining is, and for many years has been, a feature of the little placers. Men there are who are content to work with rocker in winter and dry washer in summer for the bare necessities — that is, necessities from the standpoint of grubstake miners. I once hear two partners — those miners usually work together in twos — planning the expenditure of a "clean-up." They estimated the total value at three dollars and six bits. After careful consideration of all their needs, they allotted: Four bits for flour, four bits for bacon, four bits for beans; one dollar for tobacco, one dollar for a bottle of whisky and two bits over the bar of the saloon. Strange characters have drifted into the Placerita, seeking temporary refuge from a passing storm on life's turbulent sea. The Buffalo man for whose apprehension a life insurance company offered a standing reward worked with pick and shovel to "make the dirt" to be rocked out by the "woman in the case" — the same who, later, betrayed him. A year or more of the hiding of these people was spent in the Placerita — where they mined for "grub." For sixteen years the Placerita has furnished 48,000 gallons of water daily, pumped through a four-inch pipe line, to the Pico oil fields, nine miles distant. Notwithstanding a hundred years of gold mining and a never-failing stream of water — a factor in the production of $13,000,000 of oil, nature in the Placerita seems not yet content with the blessings already allotted.

Courtesy of Stan Walker | Download .pdf Page 1, Page 2 |

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.