|

|

Click image to enlarge

| Download original scan

It wasn't exactly a secret to anyone in the Santa Clarita Valley, where teams of "Rosie the Riveters" had been packaging explosives for the past four years, but they couldn't talk about it. Now the war was won, and...

OUR SECRET'S OUT!

Now, publicly, we can thank the loyal men and women of Bermite ... and our esteemed associates in war-restricted projects ... for record-breaking teamwork that won for them on FIVE occasions the highest production awards bestowed by our armed forces and the ten million valiant Americans they represent. As their part in the cause of perpetual Peace, they loaded more than one hundred million 20-millimeter high-explosive and incendiary shells ... produced more than eight million special rocket fuzes [sic] ... supplied Chemical Warfare with special explosive parts for incendiary bombs. Not only on the production lines but in the laboratories they demonstrated their knowledge and skill and experience — representing three generations of the Lizza family — and collaborated with the California Institute of Technology on the explosive phase in the development of rocket fuzes. Full-page advertisement in the Los Angeles Times Annual Midwinter special section, January 2, 1946. Clipping saved by Mary Rübel of Rancho Camulos, whose husband August Rübel was killed in North Africa in 1943. The back side of the advertisement (page 13 of the edition), shown below, is a photo essay on the new phenomenon of Television. Already, the Mt. Wilson area of Los Angeles was becoming "one of the choice spots for television broadcasting tower sites." A "transcontinental network (of) radio relay towers" was still a dream.

The Bermite Powder Co., and Halafax Explosives Co. before it, manufactured explosives, flares and small munitions in Saugus, on a roughly 1,000-acre parcel just southeast of Bouquet Junction, from 1935 to 1987. Apparently the first on the scene was Jim "The Boilermaker" Jeffries, undefeated heavyweight champion of the world from 1899-1905. Jeffries took the helm of the L.A. Powder Co., which incorporated in 1915, and in 1917 set up a Saugus plant on the future Bermite property to manfacture gunpowder, in hopes of supplying the allied forces in World War I. By 1920 Jeffries was also drilling oil wells on the property; the success of either venture is unclear. The week of April 22, 1935, Halafax opened a $250,000 plant financed by E.P. Halliburton, an Oklahoma oil tycoon whose eponymous company would grow into one of the biggest multinational oilfield service providers. According to the California Department of Toxic Substances Control (2004), in 1939, Patrick Lizza established Golden State Fireworks on adjacent property, while Halafax manufactured fireworks at its site from 1936 to 1942. Halafax eventually defaulted on its property taxes, and Lizza's company, as Bermite Powder, acquired the ex-Halafax land from the county, apparently for the price of the unpaid taxes. Per DTSC, "The Bermite Powder Company produced detonators, fuzes, boosters, coated magnesium, and stabilized red phosphorus from 1942 to 1967. In addition, between 1942 and 1953 they produced flares, photoflash bombs for battlefield illumination, and other explosives." Bermite and the Saugus property played an important role in the needs of the U.S. military during World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam conflict. For example, the most widely used air-to-air missile in the West, Raytheon's AIM-9 Sidewinder, started production in 1953 at China Lake and used a Hercules/Bermite MK-36 solid-fuel rocket engine that would have been tested and manufactured at the Saugus plant. Bermite was a major employer and contributed to the development of Newhall in 1939 with a row of 50 2-bedroom bungalows along Walnut Street for factory workers. During and after World War II it was also a major employer of women. In the postwar period, Bermite's subsidiary, Golden State Fireworks, was testing and manufacturing fireworks on the property. Whittaker Corp. purchased Bermite Powder Co. and took over the property in 1967, operating it through 1987 as a munitions manufacturing, testing and storage facility. Among Whittaker-Bermite's products were ammunition rounds; detonators, fuzes and boosters; flares and signal cartridges; glow plugs, tracers and pyrophoric pellets; igniters, ignition compositions and explosive bolts; power charges; rocket motors and gas generators; and missile main charges. The munitions and fireworks operations left more than 275 known contaminants behind, some of which percolated into the groundwater below the property. Starting in about 1986, the operations would be exposed to steadly harsher environmental scrutiny over the next several years. "In 1987, the facility ceased all of its manufacturing, testing and storage of ordnance and explosive items," according to DTSC. Within another two years, plans were made for the area to be developed into a 2,911-unit residential community to be called Porta Bella, which was approved by the City Council but didn't come to fruition. Whittaker sold the Saugus property to an Arizona investor group in 1999, just before Whittaker was acquired in a hostile takeover. The property spent the first decade of the 21st Century tied up in litigation, one result of which is a long-term toxic chemical cleanup project managed by the Santa Clarita Valley Water Agency.

9600 dpi jpeg from original newspaper page.

|

Expansion 1943

About Patrick Lizza, Bermite Founder (1944)

Memo to Workers 1945

Bermite Ad 1946

Saturday Evening Post 10/13/1951

Security Badge

Women Assemble Fuses ~1955

Golden State Fireworks Ad 1956

Bermite Want Ad 1957

Bermite Want Ad 1961

Gold-Diamond-Ruby Service Pendant 1967-1987

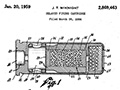

Delayed Firing Cartridge 1959

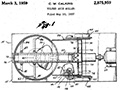

Tilted Axis Muller 1959

Multi-Stage Igniter Charge 1961

Releasable Nut 1961

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.