|

|

Tales of the Newhall Court.

Early dockets shed light on evolving ideas about crime and punishment in the Santa Clarita Valley.

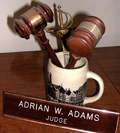

By JUDGE ADRIAN ADAMS

Saturday, April 12, 2003.

|

Editor's note: May 1 is the 50th anniversary of the day former Municipal Court Judge Adrian Adams opened his attorney practice in Newhall. His appointment to the bench by Gov. Ronald Reagan in 1970 marked the first time the Santa Clarita Valley had two judges. By the time he retired in 1991 a third seat had been added. * * * Clarence Darrow once said, "History repeats itself. That's one of the things wrong with history." My research would seem to indicate that not much has changed. The court has adjusted to the changes in laws and people's expectations, as well as to economic conditions. But Darrow probably is correct, as some of this history will show. One should remember that the court mirrors the mores of society at any given time. For example, the Supreme Court, during World War II, ruled it constitutional to compel the saluting of the American flag. After the war it changed its decision. As of now, Newhall Municipal Court is only history. With the recent unification of the courts, it has become part of the Los Angeles County Superior Courts. We do not have any formal, written history of the court. What we do have are the dockets of the court proceedings going back to the 1850s. We don't even know the names of all of the various judges who presided over the court, except as we find their names in the dockets. Originally known as the Soledad Judicial District, the name was changed to the Newhall Judicial District in 1952 as a result of action by the state Legislature. It appears there was another Soledad Judicial District in Northern California. The local judicial district was one of the largest in the state, bounded by Ventura County on the west, Kern County on the north, the city of Los Angeles on the south and the Lancaster Judicial District on the east. Actually, the line was almost to the outskirts of Palmdale, beyond Red Rover Mine Road in Acton. Until the 1960s when the Justice Court became a Municipal Court, a layman presided over the local court except for a period when Arthur Miller was the judge. In the same legislation that changed the court to the Newhall Municipal Court, the Legislature did away with the title, "Justice of the Peace," and directed those presiding to be called "judge." Let us peruse some of those dockets. As the writer has been retired from the court since 1991 he cannot even say where they are today. Hopefully they remain available to others who may want to roam through the past. * * * Newhall and Saugus were primarily train stops. Yes, they had stores and stables, but they were actually towns built to serve the railroad. Therefore the most common crimes in those early days were related to the railroad. The dockets indicate that the most common crime was "evading the payment of railroad fares." It was what we might call hitchhiking on the railroad, but without consent. The penalty for riding the rails was $5 or five days in jail. Also common was vagrancy, which cost the culprit $10 or 10 days. The writer has no information as to serving time in those days. Later, when all jail sentences were served in downtown Los Angeles, it was a way of getting the bad guy out of town. However, in those horse-and-buggy days, it was quite a trip to Los Angeles, so presumably the time was served locally. There was nothing chicken-hearted about justice. In 1907 Esignorino Hernandez got 90 days for disturbing the peace. The docket doesn't spell whose peace it was or how it was disturbed. A 1903 docket posted the county wage scale. Justice John F. Powell got a raise to $1,500. Not bad, however, because county supervisors earned only $1,800. Fines were substantially higher in those days, particularly if one considers inflation. The maximum penalty in 1900 was the same as it was during the time of the Newhall Court, with few exceptions. Of course, the alternative of one day in jail for each $1 in fines was not much of an alternative. Other typical cases found among the dockets in 1923: Picking yuccas cost $5; peddling without a county license cost $6. Fire is and was a serious wrong, and in 1933 Hannah Ahlstrom got a $50 fine for burning without a permit. One doubts that most readers ever traveled the original Ridge Route. Sections of it still exist along Interstate 5. To drive on it took courage; to speed on it took stupidity. Walther Hill drove his truck at 35 mph, 10 miles over the 1933 speed limit. It cost him $10, but not his life. Being arrested as plain drunk in the days before Prohibition cost $25, about the same as today, or 25 days. The Legislature later mandated that time credit was to be $30 per day, so fines obviously were increased so that one could get the wrongdoer to County Jail and therefore out of Newhall. Were he a local resident, other efforts could be made. For a number of reasons we find few driving-under-the-influence cases in the early dockets — certainly none of driving a buggy under the influence, as that did not appear to be against the law. Of course, Prohibition came along after World War I. The first DUI case appears to have been in 1932 when Justice Jones gave a defendant 90 days and revoked his driver's license. As Prohibition ended about that time, one can't know if it was moonshine or legitimate booze that did him in. Speaking of driving buggies under the influence not being an offense, it is a violation to ride a bicycle under the influence, and one of my clients learned it the hard way. He was arrested right in front of the courthouse. I happened to be his wife's attorney in a divorce involving excessive drinking. A phone call to the constable did wonders for his cooperation thereafter. Some famous names appear in our dockets. Attorney Earl Rogers got a murder complaint thrown out by Justice Powell in 1908. No other details are known or available in the records we have. After Prohibition became the law, the county passed a number of ordinances covering the use, production, sale and even possession of liquor. Those who are law-and-order enthusiasts would rejoice at how seriously the court enforced those ordinances. James Shannon was fined $300 and given 180 days in jail for possessing a still. The very next day, Sam Gish was in court, charged with being in a disorderly house. Sam got a 60-day sentence, suspended on the usual condition that he not do it again — that is, get caught. No mention is made of the lady or ladies involved. Perhaps that's because women had just gotten the right to vote and hadn't had a crack at straightening out such obvious sexism. For an example of cruel and unusual punishment, take the matter of disturbing the peace that was heard by Justice Arthur B. Perkins in 1926. He gave John Hooper the Hobson's choice of 30 days in jail or parole to his wife for one year. Sounds like a good case for an appeal. Some of you may remember Art Perkins, the longtime historian. Art was the nicest and most gentle person you'd want to know. In 1928 he didn't waste time in sentencing lawbreakers who were broke. Luis Klein appeared for selling liquor. "Three hundred dollars," said the justice. Luis responded that business had been bad and he was broke. The justice promptly amended his sentence so he could sit it out at $1 a day. One case of Justice Perkins' in 1926 also involved alcohol. He ordered the constable to take the "liquor confiscated to Olive View Sanitarium, destroying what they do not use." The method of destruction is not specified, but one can speculate about the time it took the constable to return, and about his method of destruction. He probably took the Ojai turnoff by mistake. * * * Learn more about the Santa Clarita Valley's horse-and-buggy days on the Internet at scvhistory.com, or stop by the Saugus Train Station Museum in Old Town Newhall, Saturdays and Sundays from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m.

©2003 Adrian Adams | Originally published in The Signal | Used by permission. |

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.