|

|

Eyewitness to the 20th Century

Paul and Barbara (Sitzman) Cook.

Happy Valley Poultry Farming (Paul), Mentryville School Days (Barbara).

The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise | Wednesday, September 4, 1985.

|

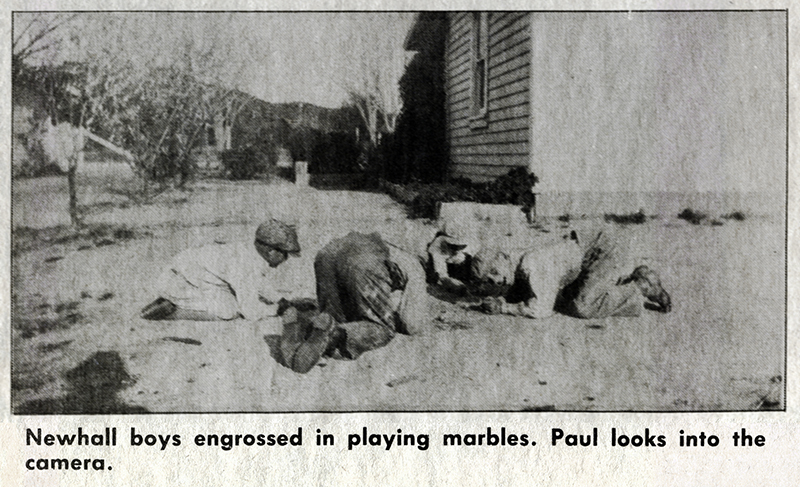

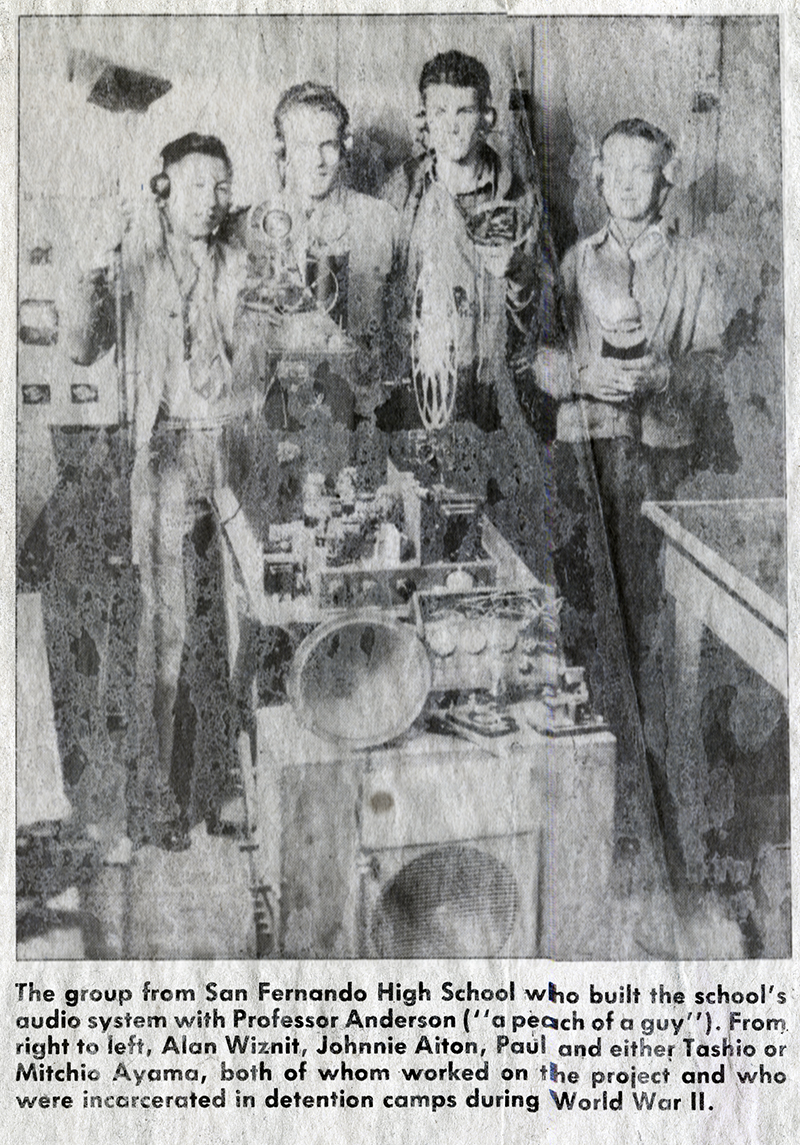

When Lyons Avenue — then called Pico Road from Newhall Avenue to Pico Canyon — was what Paul Cook called "just a two-rut road right on through," people "knew everyone in town and most of the people from the outlying areas," Barbara Sitzman Cook said. "This is like a city now, compared to what it was when we came here," Paul said. The biggest changes that Paul and Barbara Cook see in the Santa Clarita Valley since they were growing up in the 1920s are the boom in shopping centers and the attitudes of the people. "People are not as friendly as they used to be, not nearly," Paul said. "Used to be, everybody knew everybody else, and practically everybody else's business, too." Some might feel there is an advantage to the anonymity of the bigger town feeling of today, but the Cooks clearly prefer knowing people, with all the advantages and disadvantages of doing so. Paul feels the difference in friendliness has to do partly with the sheer numbers of people, and partly to do with television. "There's just too many people. It's built up too fast." Barbara continued, "you can't hardly find anybody anymore." "Now I walk downtown and I don't know anybody," Paul agreed. When Barbara and Paul were young, they used to speak to everyone on the street. Since "now you can't even find people you know, it makes a big difference in the amount of trust you put in things." People have more fear, the Cooks said, because we don't know who is around us anymore. Back then, someone stealing things was unheard of, and people didn't even have locks on their doors. Also, television "changed everything. It changed every way of life," Paul said. The TV keeps people indoors and from visiting each other like they used to, Paul and Barbara agreed. Friends would just drop by in the old days or call first to ask if it was a good time to come by or to extend an invitation. When they would have spent the evening at a church supper, people now sit in front of the TV. A television is conspicuously absent from the cozy living room of the Cooks' mobile home. "I wouldn't have it," said Barbara, who keeps the TV tucked away. * * * Paul's parents were "ordinary people," his dad a farmer and his mother a housekeeper. (Barbara interjected: "a good cook and a good canner.") They were originally from Ohio and moved from Huntington Beach to Newhall when Paul was 3 years old. They moved to a house where the ice plant is now, near the corner of San Fernando and 5th Street, while his father began to build the house on Valley Street where they were to settle and start an egg farm. After they moved to the 5-acre farm between 8th and Apple streets, A.B. Perkins bought the 5th Street house, built a tepee to attract customers, and set up shop to sell real estate. A.B. Perkins "was quite a character around town" and ran the only water company here at the time, Paul said. So, he could afford to be buying up houses, "'though then water was cheap. It wasn't anything like it was now," Paul said. Later Perkins built a house out of the wood from the old Newhall school, on the corner of Kansas and Lyons. (Perkins also wrote a history column for The Signal in 1964.) (Webmaster's note: And at other times.) There was only one lumber yard in town in those days, too. During the chickens' lull seasons, Paul's father worked for Hammond Lumber Company. The lull season depended on when he would buy another batch of 500 or 1,000 day-old chicks to keep his laying hen population up around 5,000. He bought the chicks from the Gibson Ranch on Market Street, or from Petaluma in Sonoma County, shipped by train. He would sell the cockerels and keep the hens for eggs. The chores on the egg farm were a sunup to sundown job for young Paul, who to this day cannot stand chickens. "As far as I'm concerned, I hated it." So, it was a bit of a relief to Paul when the Depression hit and the Cooks had to sell almost all their chickens and equipment, keeping only enough for the family's use. The price of eggs had gone down, and feed had gone up. Not many egg farmers survived. "We just about broke even, but quite a few of the egg farmers around here lost money, and some of them lost their ranches." Eggs cost 10 cents a dozen, and milk, 10 cents a quart. The Cooks always had a cow and would sell a few quarts here and there. His dad's big garden, as well as the odd jobs he picked up and his work in the lumber yard, helped them survive those hard times. But even the garden grew too expensive to hold onto, and he had to sell off part of the land to pay the water bill, even though "it wasn't very high." Paul loved to go rabbit and coyote hunting back in the hills around Happy Valley and Peachland Avenue. There was nothing but sagebrush there then, and coyotes that would steal chickens whenever given the chance. "Once in a while you could hear a mountain lion back in the hills squalling, and once in a long while you'd see them down in the valley." Paul learned to shoot "as soon as I was old enough to carry a gun." The coyote was not killed for meat, "because they were too much like a dog." But a bounty was paid on the hide, "because they were a nuisance, there were so many of them." Paul bemoans the burgeoning of the new breed of hunter. "There's too many out there that shoots at anything that moves. I'm afraid to go hunting anymore." His wife Barbara also learned to hunt as a small child. "One of my first memories is learning to shoot." She reminisces about the sage-y flavor of the dove, quail and rabbit she brought home to eat. * * * Guns weren't the only things that took life. On March 12, 1928, the San Francisquito dam broke and the whole valley was affected. Fortunately, the water rushed through the Santa Clara river, bypassing the towns of Newhall and Saugus. Still, many lives were lost in the canyon, even if a newspaper's report that Saugus and Newhall were washed clear off the map was laughable. Almost everyone lost a friend or more. "We lost some friends in the different ranches up there," Paul said. Paul's sister, Naomi, worked for the Red Cross, and all the able-bodied men went up the canyon to help rescue who they could and find bodies. Newhall Community Hospital was set up as a morgue. Paul, still a boy, helped sell the Herald Examiner around town. * * *

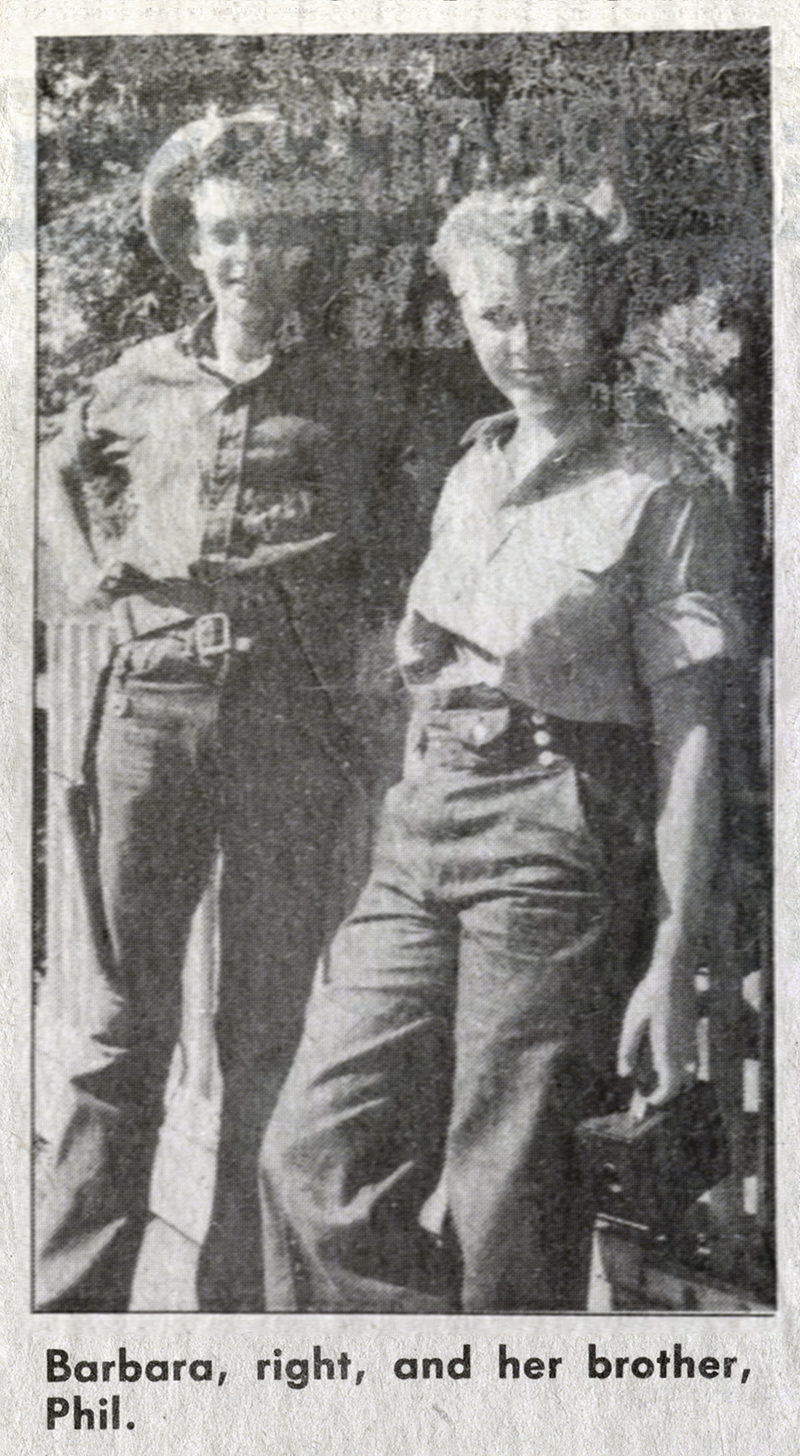

Barbara's father, Charles Sitzman, was from Ohio and met his Californian wife, Emma, when he moved to Los Angeles. He worked for Standard Oil, so they lived on a series of Standard Oil leases for 10 years. Barbara was born on a lease in Tupman (near Taft) when Charles was 46. The family, including an older son, Phil, moved from Seal Beach to Pico Canyon on October 19, 1927. Barbara was almost 6. Emma told Barbara that they must have moved three times a year before they came to Pico. But by the time they moved to Pico, Charles was an oil field supervisor, and the family settled down. Barbara loved growing up in Pico Canyon. "We had a ball," she said. "We must have played hopscotch on every piece of dirt in Pico." She fondly recalls her school days at the Felton School, where there were 17 pupils in eight grades. She has helped with Frenchy and Carol Lagasse's restoration of the schoolhouse. The school still has reunions every year. The October 12 reunion this year will celebrate its 100-year anniversary. The shock was great for Barbara to move from being in a class of 38 students in the first grade at Seal Beach to being the only one in her grade at the Felton School, in a classroom with first- through eighth graders. She feels that the one-room school had some definite advantages: The children each received plenty of attention, and listening to the lessons for the older children, even if they were somewhat over the younger ones' heads, influenced and enticed them to learn more. "We could always pick up something" from the older children's lessons, Barbara said. When the Dill family with its 12 children moved away, the school no longer had enough students to stay open. Barbara started going into Newhall to go to school in sixth grade. After eighth grade she went to San Fernando High, as Paul did. There was a dance hall next to the Felton school, but after a while there were not enough people dancing, and it was used for a classroom to teach first aid, an essential skill in an oil field, Barbara said. The village there was named Mentryville, after Alex Mentry, an earlier supervisor of the oil field. Barbara grew up in Mentry's second house, which was the only one in Mentryville with indoor plumbing. That building, too, has recently been restored by the Lagasses. Barbara remembers when the Ridge Route to Bakersfield, which is now The Old Road, was built. The road builders forgot to leave an egress to Pico Canyon. There was a 6-foot drop from the new road that "left Pico Canyon high and dry." No one could drive in or out until Charles complained and had the road crew come back to fix it. In those days, Barbara said, when people who owned a house moved, they would dismantle the house and move it to the new location. Lumber was rare and and labor cheap. Families would have to move off the lease if the worker was laid off, "but my dad always tried to hire back the same ones who had been laid off." Charles was "a big man, very friendly and jolly," and Barbara loved to ride around with him to the old Elayon refinery to which Standard Oil pumped its crude, or wherever he needed to go. Barbara's mother, Emma, was crippled with arthritis from as early as Barbara can remember, but she was always there for her and her brother Phil, baking cookies or something. The children were always welcome to bring home friends, and after the family moved to town in 1937 and Barbara became involved in the Christian Endeavor Society, she often brought home kids from the group after a meeting. The Christian Endeavors was the youth group of the Community Presbyterian Church, one of the two churches in Newhall at the time. The other was the Catholic Church. Everyone got along from both churches, with very little friction. The Presbyterian church had a Christmas play every year, to which they would invite the Catholic children. The Presbyterians' Reverend Evans, a long-white-bearded man who was "everybody's friend," was part of the reason for the good relations between the churches. Paul remembers Rev. Evans visiting everyone, including Catholics, all the time. Paul and Barbara met at an outing with the Christian Endeavors. About 30 kids went out to Camp Comfort in Ventura where they ran into some folks from the Ventura Baptist Church who invited them to their service that evening. The campers, even in their Levis and boots, could not refuse the hospitality of their newfound friends. Soon afterward, Paul and Barbara began "going together," and two years later they were married. The new couple moved into a small house across 6th Street from the Community Hospital. The first few years of their marriage were "pretty tight," since the Depression had not quite lifted. "You always counted your money before you went out," Paul said. Rent was only $22 a month, but Paul's take-home pay was not much more, at $22.80 a week. Paul worked for Lockheed in Burbank, making Navy equipment. So, during the war, although the draft board kept telling him he was going to war, Lockheed kept telling him they needed him and that he was going to stay at home to do his part for the war effort. Finally, the public and private organizations ironed out their differences, and Paul stayed home. "I was ready to go, though," Paul said. The Cooks' three sons — Milton, Keith and Merle — were born in the war years at the Newhall Community Hospital. Paul was with Barbara for each birth, although it was no longer the custom for fathers to participate. "We knew Dr. Innis, and he trusted Paul, so he let him in. He wouldn't let all the fathers in," Barbara said. The doctor gave Barbara ether, so she wasn't completely knocked out for the births. "I was just kind of floating," she said. "In those days, you had to stay 10 days at the hospital." The doctors still did some home deliveries, but they were becoming rarer and rarer. During the war, people complained about the rationing and the difficulty acquiring things. But they were just little inconveniences, the Cooks said. Few of the inconveniences made people aware of what the war was really like as the blackouts did. During a blackout, air raid sirens would blare, and block wardens would come around, wearing tin hats and arm bands, to insure that everyone had turned out all their lights and pulled their drapes tight around the windows to hide any light. Drivers would have to turn off their headlights; the whole town would pretend it didn't exist. * * * Bringing up children today, Barbara said, must be so much more difficult than it was for her. With nothing to do but watch TV and play video games, the children get alienated, she said. Not knowing what to do with themselves, they get in trouble. "Kids today don't even know what a hike is. They're victims of the times," she said. Children used to roam free, hunting and climbing trees and hills, without their parents needing to worry about kidnappings. Today, with all the pavement, you can no longer ride a horse around town safely, she said. She can remember being bucked from a black donkey every time she started it galloping. She would never have been able to work with that donkey in a town full of pavement. "Let's just say I don't approve of ruining everything with houses," Barbara said. "They've cut down enough hills and covered enough land with houses already. It's more than enough."

This is the fifth biographical profile of The Signal's second series of "Eyewitness To The 20th Century." The series concludes Friday with Willis Dyer.

Download individual pages here. Clipping courtesy of Cynthia Neal-Harris, 2019.

|

CSOW Time Book

1887-1889

Charles E. Sitzman

Oral History: Barbara Sitzman Cook 1988

Pico Cyn Marker Tree 1920s/30s (Mult.)

Soledad Hotel ~1920s

Standard Oil Origin Story 1929

Pico Kids, 1930 Restoration

Pico Oilmen, Pioneer Refinery ~1930

CSO Jackline Plant

C.E. Sitzman Obituary 1950

Paul & Barbara Cook Story 1985

Artifact Donation Story-1

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.