|

|

HISTORY OF THE SANTA CLARITA VALLEY BY JERRY REYNOLDS

[NEXT] [PREVIOUS] [CONTENTS] [SEARCH]17. Yanks Infiltrate

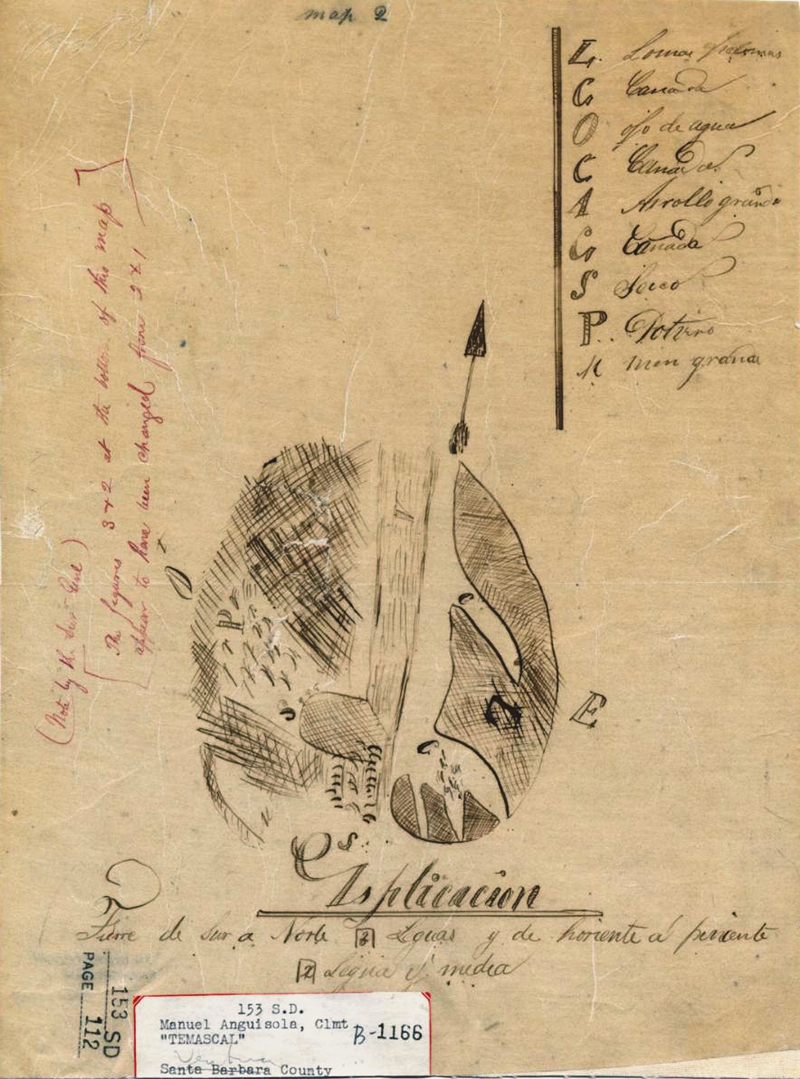

Diseño del Rancho Temescal in Ventura and Los Angeles counties, granted to Francisco Lopez in 1842. Diseño map in Bancroft Library. Click to enlarge.During summer of the year 1800, the American brig "Boston" sailed into the harbor at San Diego, much to the surprise of Spanish authorities. There was an official ban on trade with foreign ships; however, the Yankee sea captain was willing to lay out good money for tallow and a dollar for each cow hide.

A year later the ship "Enterprise" put into port, laden with shoes and boots made from California leather. Thus was born the hide-and-tallow trade that turned patrons and priests alike into smugglers. Occasionally a sailor would jump ship, enamored by the climate, the easy living, or perhaps a señorita.

One such deserter was a Frenchman named François Chari, who took an oath of allegiance to Mexico and changed his first name to Francisco. Chari later journeyed up into the Cañada de los Robles (Scrub Oak Canyon) and, impressed by what he saw, purchased several hundred acres from Doña Jacoba del Valle Salazár. In 1843 he established El Rancho del Buque (Ship Ranch), settling down to raise cattle and children. "Buque" would later be misspelled "Bouquet," changing the meaning from "ship" to "flowers."

Meanwhile, gold discoverer Francisco Lopez had become lord and master of Rancho Temescal. He picked up another nugget in San Feliciano Canyon, much of which is now covered by Lake Piru, and touched off another rush to riches.

Aristocratic Californios would not grub about in the muck and mire, so it was the Sonorans again who did most of the work. One exception was José Salazár, Doña Jacoba's second husband, who placered $4,300 in a year. Even more fortunate was José Espinosa, who plucked a six-pound, four-ounce lump of gold from Las Palomas Canyon.

Richard Henry Dana, in his Two Years Before the Mast, writes: "We also carried a small quantity of gold dust, which Mexicans or Indians brought to us from ... San Feliciano Canyon, not far from Mission San Fernando."

According to Dana, it was not uncommon for Yankees to carry gold back to New England, possibly sparking an interest in California. As early as 1835, President Andrew Jackson attempted to buy San Francisco from Mexico for a half-million dollars. The offer was politely but firmly refused.

Ten years later James Knox Polk was elected president on the strength of promises to reduce tariffs, establish an independent treasury, settle the Oregon boundary dispute with England and, most importantly, "to secure the admission of California" to the Union.

One of Polk's first acts was to offer Mexico forty million dollars for her province. When that failed, Polk ordered a program of infiltration, encouraging pioneers to settle in the region.

Mexico unwittingly made the process easier. People like Abel Stearns, William Wolfskill and John Temple were allowed to migrate, convert to Catholicism, become citizens, marry the daughters of rancheros, and become a small army of "fifth columnists" under the direction of the president's personal agent at Monterey, Thomas O. Larkin.

Their purpose was to foment revolt, and they did not have to try very hard. Many of the leading citizens, including Vallejo, Pio Pico and Ygnacio del Valle, concluded that California would be better off under American rule than Mexican.

They might have handed the state over to the U.S. without a shot being fired had it not been for the bungling of bureaucrats and the untimely arrival of an aggressive, egocentric, ambitious captain of topographical engineers — John Charles Frémont.

©1998 SANTA CLARITA VALLEY HISTORICAL SOCIETY · RIGHTS RESERVED.

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.