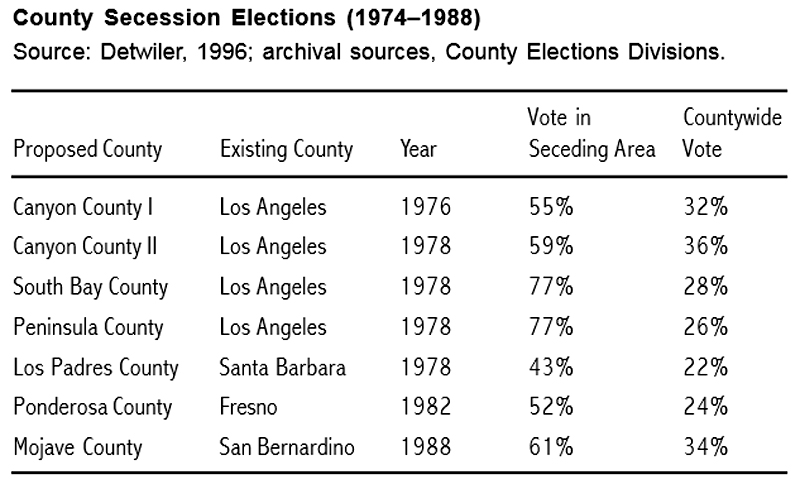

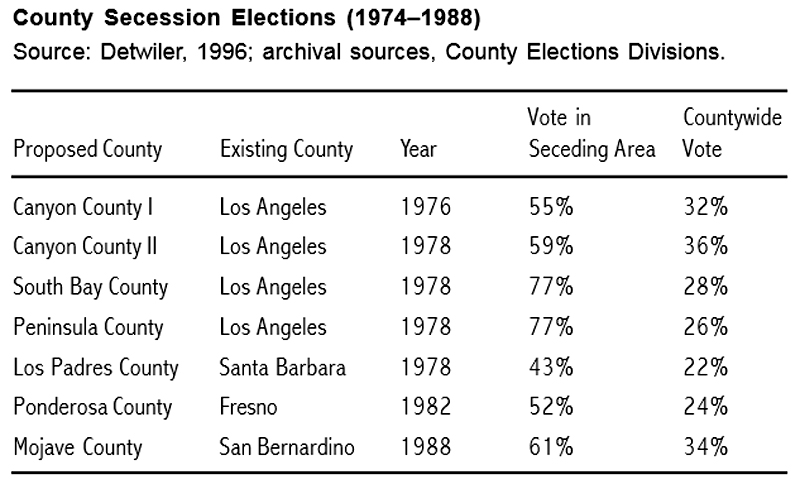

Election results: County secession efforts in California, 1974-1988. Note that the Canyon County formation effort passed both times in the affected area (SCV) but lost in the

county as a whole. Chart from "Anatomy of a Defeat: Why San Fernando Valley Failed to Secede from Los Angeles" by Tom Hogen-Esch and Martin Saiz, California State University Northridge, published in "California Policy Issues," November 2001. Click to enlarge.

|

The Santa Clarita Valley's population literally exploded during the 1960s, jumping a dramatic 250 percent.

Over the next ten years this increase slowed to just forty-two percent, with the 1980 census recording 81,816 residents. This represented 1.1 percent of the total population of Los Angeles County — a small portion, yet an increasingly vocal one. Like their pioneering predecessors, newcomers and old-timers alike were becoming frustrated with a distant bureaucracy that seemed indifferent to their needs. It was taxation without representation!

There was tremendous pride in the area's schools, churches and public buildings. Valencia was one of the best-planned communities in the country. Bermite was building sophisticated weaponry. Hydraulic Research helped put men on the moon. Visitors came from all over the world to visit Magic Mountain and to study the water project at Castaic and Pyramid lakes.

In spite of this cosmopolitan development, the county's rulers in downtown Los Angeles seemed to continue to picture the Santa Clarita Valley as some sort of rural backwater.

To achieve some measure of "home rule," studies were conducted to determine the feasibility of incorporating Newhall, Saugus and Valencia into a city. Spearheading these efforts were Carl Boyer III, a slender, sandy-haired educator; and H. Gil Callowhill, a retired businessman. A petition drive was begun in 1973, but local residents weren't quite ready for such a move.

During 1974 a meeting was held to rekindle the flames of city formation. Signal co-editor Ruth Newhall suggested that these rebels secede altogether from the County of Los Angeles. That December a new committee was formed to lead the fight to break Acton, Agua Dulce, Gorman, Castaic, Val Verde, Canyon Country, Saugus, Valencia and Newhall off from Los Angeles County. The new entity was to be called Canyon County.

Dan Hon, a local attorney, co-chaired the group with Connie Worden, a well-informed Valencia resident who involved herself in many community activities. Lee and Frank Turner, owners of the Lyons Bowl, headed up publicity. Bill Light gathered petitions, while Art Evans and Jan Heidt rounded up financial backing.

These and many other people collected the requisite number of valid signatures and submitted the paperwork to Governor Edmund G. "Jerry" Brown, Jr., for a commission to be appointed to study the feasibility of the new county. After nine months the five-person panel finally met on April 26, 1976 in — where else? — downtown Los Angeles. At last, in August, they concluded that Canyon County could get along very well on its own, so the measure was placed on the November ballot as Proposition F.

Under state law, the creation of the new county would have to be approved by all the voters in the existing county — not just those of the Santa Clarita Valley. County employees, particularly firefighters, spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to convince Angelenos that Canyon County formation would cost them money and jeopardize services.

On the night of November 2, 1976, hundreds gathered at the Mint Canyon Elks Lodge. Present were Jo Anne Darcy, George Wells, Bonnie Mills, Jan Heidt, Alice Kline, Ken and Anne Lynch and many others who had worked long and hard.

The festive atmosphere deteriorated around midnight when it became apparent that, while Canyon County was approved locally by fifty-five percent of the voters, it had gone down to defeat in the county at large by a margin of sixty-eight to thirty-two percent.

As if to add insult to injury, five people, including Boyer, were elected supervisors of the new county in the day's polling. But with Canyon County a non-entity, they were the supervisors of nothing.

Out of the rubble of despair rose a second attempt, joined by other regions trying to secede, and even a proposal to carve Los Angeles into five separate counties. Faced with fragmentation and loss of power and position, the county supervisors rushed a bill through the state Legislature requiring that any new county must have a minimum population of five percent of the mother county. Just fifteen days before the new law went into effect (January 1, 1978), new Canyon County formation petitions were delivered to the registrar's office, wrapped up like a Christmas present. The great rebellion was off and running again. This time it was Proposition K on the November 7, 1978 ballot and was, as before, approved locally by fifty-nine percent of the voters but defeated in the county at large.

The wheel of history then turned full circle, for no sooner than the dust settled were the rabble-rousers polishing off their old cityhood ideas. This time they would try to incorporate not just Newhall, Saugus and Valencia, but the whole region that might have been Canyon County, into one giant city.

This time the outcome would be different.