|

|

|

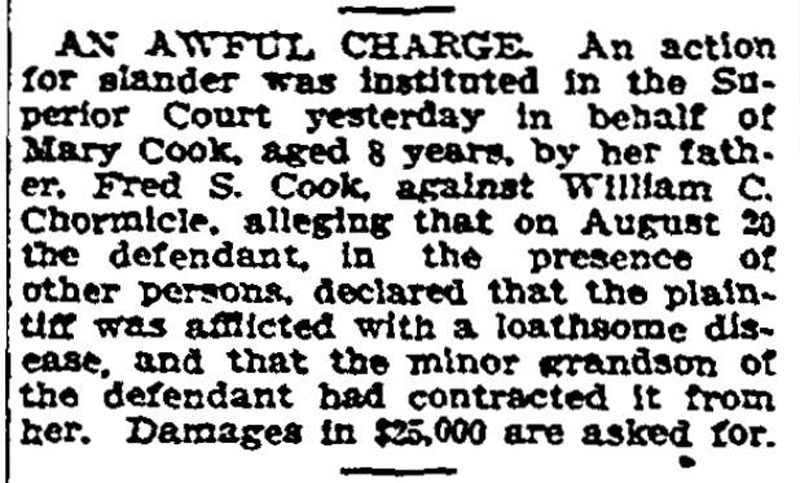

An Awful Charge. Los Angeles Times | Friday, September 16, 1910. An action for slander was instituted in the Superior Court yesterday in behalf of Mary Cook, aged 8 years, by her father, Fred S. Cook, against William C. Chormicle, alleging that on August 20 the defendant, in the presence of other persons, declared that the plaintiff was afflicted with a loathsome disease, and that the minor grandson of the defendant had contracted it from her. Damages in $25,000 are asked for. News story courtesy of Tricia Lemon Putnam.

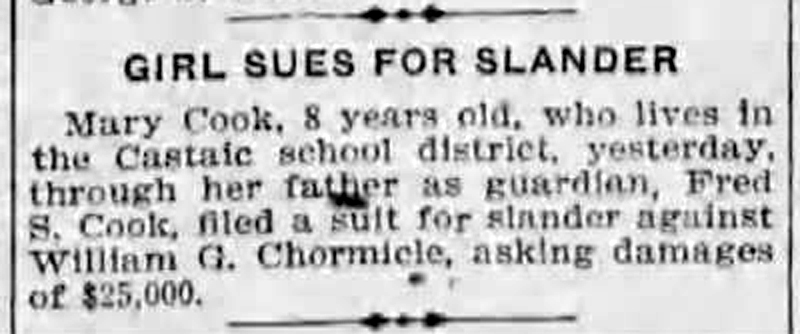

Girl Sues for Slander. Los Angeles Herald | Friday, September 16, 1910. Mary Cook, 8 years old, who lives in the Castaic school district, yesterday, through her father as guardian, Fred S. Cook, filed a suit for slander against William G. [sic] Chormicle, asking damages of $25,000. Webmaster's note. Mary Cooke, a Fernandeño Indian of Tataviam, Kitanemuk and Tongva descent, went on to become Chief of the Southern Chumash, inheriting the title from her mother (Fred's wife), Frances Garcia. The "e" was added to the Cook surname by Fred and Frances. Fred was a son (and Mary, a granddaughter) of Mr. Dolores Cook. News story courtesy of Lauren Parker. Webmaster's note. Castaic rancher William C. Chormicle and ally Will A. Gardener shot Mr. Dolores Cook and settler George Walton to death on Friday, Feb. 28, 1890. Cook and Walton were allied with Chormicle's bitter enemy, Castaic landowner William Wirt Jenkins, a onetime member of L.A.'s vigilante police force (the Rangers) during the rough-and-tumble 1850s. Walton was a newcomer to the area, but Cook was a Fernandeño Indian of Tataviam, Kitanemuk and Tongva descent, and Castaic was his ancestral territory. Upon his death, Cook left a widow and four children. Cook is the late Charlie Cooke's great-grandfather. Charlie Cooke (1935-2013) was chief of the Southern Chumash and a respected elder within the Fernandeno-Tataviam Band of Mission Indians. (The "e" was added to the surname by Charlie's grandparents.) Dolores Cook is also gr-gr-grandfather to the current (2014) chief, Ted Garcia, who was passed the title from Charlie in December 2008. An initial inquest into the killings by the local judge — none other than Judge W.W. Jenkins — pointed to murder. During the coroner's inquest, all eyewitnesses said the victims never fired their weapons. Nonetheless, the tables turned to self-defense when the case went to trial in Los Angeles. There were more than 100 persons on the witness list, but none dared testify against Chormicle, who had a reputation for being armed and irascible. The defendants were acquitted. There are members of the Cooke-Garcia family today who believe justice was denied. The blood feud boiled over several more times and claimed as many as 21 lives. It all related to a property dispute among the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad, the Southern Pacific and the U.S. Government. Chormicle claimed to have purchased 1,600 acres of land in Castaic from the railroad, while Jenkins and his friends believed they had rights under the Homestead Act to settle much of the same land. The dispute among the railroads and the govenrment was still working its way through the court system when Cook and Walton were killed. The Chormicle-Jenkins rivalry came to a head after 1913 when a forest ranger who'd been sent by the government to keep the peace departed. Chormicle shot then-Old Man Jenkins in the chest. He survived. Not long after, Chormicle was shot and killed. Locals blamed Jenkins. Also in 1913, Jenkins was shot off of his horse by Billy Rose, a Chormicle ally. Again Jenkins survived. Three years later Jenkins died of an illness while visiting friends in Los Angeles. He was 84. Epitaph: It is likely that some of the Jenkins people who were killed in the long-running feud were buried here.

|

SEE ALSO:

••• SERIES •••

• Pollack Story 2014

Story of Bill Jenkins

Kreider 1952

W.C. Chormicle

Chormicle Allies Start a School, 1889/90

Land Feud Goes to Court 1890

Chormicle's Son Arrested 1890

Dolores Cook Land Patent 1891

Suen Murders Aceda 1895

Chormicle Sued for Slander 1910

SEE ALSO: Lazy Z (Jenkins Ranch) Graves Unearthed 1998

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.