|

|

Survivors from the Edison Camp at Kemp.

News reports 1928.

|

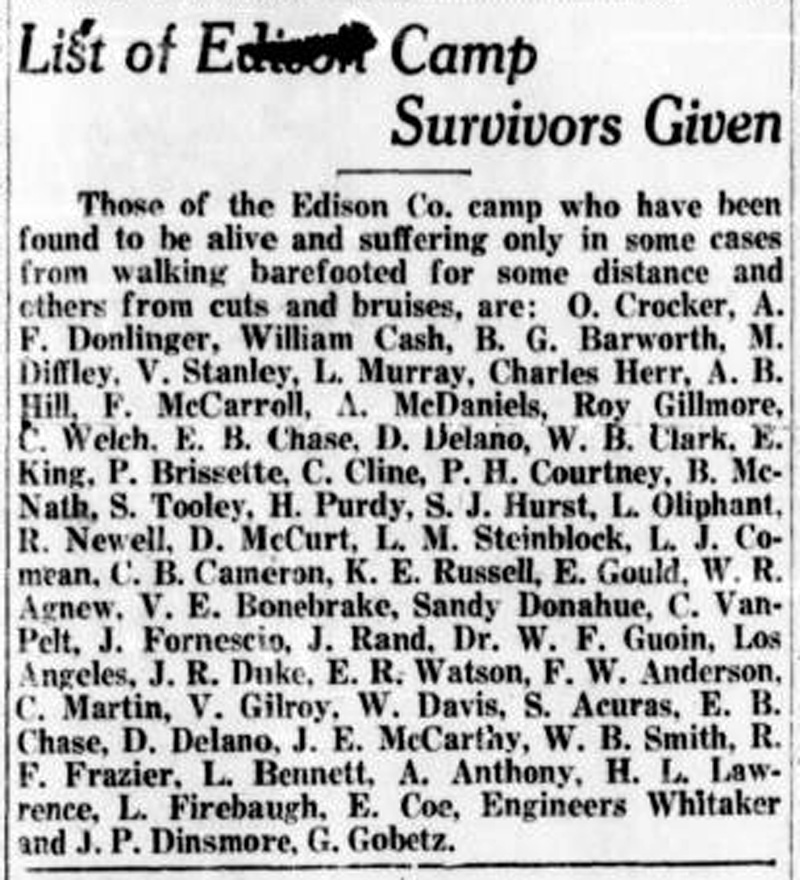

List of Edison Camp Survivors Given. Santa Paula Chronicle | March 14, 1928 pg. 2. Those of the Edison Co. camp who have been found to be alive and suffering only in some cases from walking barefooted for some distance and others from cuts and bruises, are: O. Crocker, A.F. Donlinger, William Cash, B.G. Barworth, M. Diffley, V. Stanley, L. Murray, Charles Herr, A.B. Hill, F. McCarroll, A. McDaniels, Roy Gillmore, C. Welch, E.B. Chase, D. Delano, W.B. Clark, E. King, P. Brissette, C. Cline, P.H. Courtney, B. McNath, S. Tooley, H. Purdy, S.J. Hurst, L. Oliphant, R. Newell, D. McCurt, L.M. Steinblock, L.J. Comean, C.B. Cameron, K.E. Russell, E. Gould, W.R. Agnew, V.E. Bonebrake, Sandy Donahue, C. Van Pelt, J. Fornescio, J. Rand, Dr. W.F. Guoin, Los Angeles, J.R. Duke, E.R. Watson, F.W. Anderson, C. Martin, V. Gilroy, W. Davis, S. Acuras, E.B. Chase, D. Delano, J.E. McCarthy, W.B. Smith, R.F. Frazier, L. Bennett, A. Anthony, H.L. Lawrence, L. Firebaugh, E. Coe, Engineers Whitaker and J.P. Dinsmore, G. Gobetz. News story courtesy of Ann Stansell.

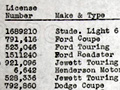

"Grim death dealt a cruel blow at Kemp," writes St. Francis Dam historian John Nichols (2002:37), referring to a rail siding and a temporary Southern California Edison construction camp west of Castaic Junction. "(T)he mountain of water hit without warning" on March 13, 1928, at 1:20 a.m., about 83 minutes after the dam broke in San Francisquito Canyon. Some 150 Edison linemen had been stringing a power line from Saticoy to Saugus, Nichols writes. They were camped on the opposite bank of the dry Santa Clara River bed from Blue Cut, an outcropping of bedrock just east of the L.A.-Ventura County line. The floodwaters lashed against the rock and whipped back over the drowsy workers who'd been asleep in their tents, dealing them a double dose of disaster. Eighty-four perished, Nichols writes. "From our observations," Almer and George Newhall report on behalf their eponymous company, property owner Newhall Land, "it seem(s) to us that the terrific loss of life and damage caused to this construction camp was due to the backwash of the water when it struck the Blue Cut Promontory and was diverted first north and then southwards back across the track into the body of the stream again." "One of the witnesses told us that the water, when the flood first struck them, must have been at least 20 feet deep; in fact the water marks on a remaining telegraph pole there seem to bear out his statement," they write. The Newhalls' report is dated March 24, 1928, and accompanies photographs they shot along the flood path where it ran through their property from Saugus (Seco Canyon) to Piru. They describe how their photos "give some slight indication of the terrific force with which this backwash of the flood waters engulfed the men (at Kemp), showing respectively a freight car torn from its trucks and tipped over; a group of reels of copper cable weighing approximately 26,000 lbs. each moved from alongside of the railroad track out into the middle of the field 500 feet or more; and a close-up photograph of a few of the wrecked automobiles that belonged to the old construction gang. ... (Y)ou will notice these automobiles scattered all over the entire field and ... a steam crane being used to right some of them. "An interesting point is that while the automobile bodies, machinery and tops were very seriously damaged," they note, "we did not see a single instance where one of the tires was broken."

Construction on the 600-foot-long, 185-foot-high St. Francis Dam started in August 1924. With a 12.5-billion-gallon capacity, the reservoir began to fill with water on March 1, 1926. It was completed two months later. At 11:57:30 p.m. on March 12, 1928, the dam failed, sending a 180-foot-high wall of water crashing down San Francisquito Canyon. An estimated 411 people lay dead by the time the floodwaters reached the Pacific Ocean south of Ventura 5½ hours later. It was the second-worst disaster in California history, after the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906, in terms of lives lost — and America's worst civil engineering failure of the 20th Century.

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.