|

|

Treaty Between the United States and the Indians of

"Castaic, Tejon, Etc.," 1851.

With Heizer (1972).

|

Webmaster's note.

Mexico City's plan, with the secularization of the Spanish missions, was to return most ex-mission lands in Baja and Alta California to the Indians. It didn't work out that way. Corrupt Mexican officials in Alta California gifted (granted) most of the land to friends and allies, often without the knowledge or blessing of the faraway Mexican central government. With the American takeover in 1846-1848, the United States government agreed in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo to honor land rights as they existed under the previous (Mexican) regime. On March 3, 1851, Congress approved the Land Claims Act, which set forth a process for proving claims. Land titles that couldn't be perfected within two years would pass to the federal government as public domain, available for homesteading. Two years was a pipe dream. Title to the Rancho San Francisco — 48,000 acres of formerly Indian land in the Santa Clarita Valley that the Californio governor gave to his Mexican Army buddy Antonio del Valle in 1839 — was affirmed in 1858. The patent itself wasn't issued until 1875, long after Antonio was dead and his heirs had lost the property to money lenders. But we're getting ahead of ourselves. The 1851 Land Act was the basis for most of what followed, but it wasn't the first or the only piece of legislation relating to land ownership in the new state of California. Immediately after statehood on Sept. 9, 1850, California's two U.S. senators, John C. Fremont and William M. Gwin — a slaveowner from Mississippi who controlled California's political machine throughout the 1850s — proposed to extinguish any and all Indian land claims. It happened, but not right away. The U.S. Senate authorized, and President Millard Fillmore appointed, three commissioners to negotiate treaties with the California Indian tribes — George W. Barbour, Redick McKee and O.M. Wozencraft (who later kept a Yuki Indian girl as a slave in his home). What they did was, in the words of Stanford University anthropologist Robert F. Heizer (1972), "a farce from beginning to end." The three commissioners arbitrarily divided California into 18 regions. In 1851 and 1852 they negotiated treaties with more or less random groups of people. As Heizer notes, the commissioners had no comprehension of the fact, first of all, that Indians didn't consider themselves "owners" of land, in the legalistic American sense; and second, that there was no political structure or "tribe" covering one-eighteenth of the state's land mass. Each of the 18 regions contained numerous ethnic groups, and each of California's ethnic groups consisted of several small, autonomous tribelets with their own clan leaders and no supreme "chief" comparable to the Great White Father in Washington, D.C. The Indians who were selected by the commissioners to sign treaties simply weren't in a position to dispose of land they didn't "own" — not to mention land where some other, unrelated and unrepresented clan lived. To put it into context, Treaty No. 4, alternately Treaty D, was titled "Treaty with the Castake, Texon, Etc., 1851." Well, the "etcetera" was an enormous expanse of land covering the entire coastline from today's Santa Maria to Lompoc to Santa Barbara, Ventura, Los Angeles and Long Beach — and stretching eastward into the Mojave Desert to a point between Barstow and Las Vegas. Negotiating such a treaty would be like somebody in Solvang bartering away some other family's homeland in Riverside. It was insane. "Rarely, if ever, in United States history, have so few persons without authority been assumed to have had so much, and given so much — for so little in return — to the federal government," Heizer writes (1972:5). The treaties relegated to the Indians — who rendered their names as an "X" and weren't necessarily made to understand what they were signing — a relatively small patch of land for their "sole use and occupancy" while the remaining bulk of the territory within each of the 18 regions would be "ceded" to the United States. Treaty No. 4 called for the Indians of the Santa Clarita Valley (and all other Indians from today's Santa Maria to Long Beach to Barstow) to live in the southern San Joaquin Valley. The reserved land — part of which soon became the short-lived Tejon Reservation under the direction of Edward F. Beale and his agent, Alexander Godey — extended from the Tejon Pass on the south to the Kern River fork just above Kern Lake (then called Carises Lake) and the (now dry) Buena Vista Lake on the north. It was essentially the north side of the Grapevine as we know it today, from the western Tehachapi foothills to a point about halfway to Bakersfield. Under the treaties, the Indians would forfeit the balance of the land. (Other than the particular property descriptions, the clauses of the 18 treaties were boilerplate.) In return for the reserved land, the Indians would, by treaty, "forever quit claim to the government of the United States ... any and all other lands to which they or either of them now have or may ever have had any claim or title whatsoever." The U.S. Senate never ratified the treaties. In fact, the United States government never ratified any treaty with any tribe in California. It didn't want to give up rights to any land at all. The Senate wished the 18 treaties away, hiding them under lock and key until they were unsealed in 1905, by which time the plight of Indians in California and the Southwest was beginning to register on the public conscience. In 1852, it hadn't. Gold fever was at high pitch, and the California Legislature didn't want anything or anyone to stand in the way of further immigration and exploitation of the natural resources. The federal government reorganized California Indian affairs under one overseer instead of three commissioners — namely, E.F. Beale. With no rights to the Tejon or any other land, Indians from as far away as the Owens Valley were brought to the Tejon (aka San Sebastian) Indian Reservation. But it was not to last. In 1858, just as it did with the Rancho San Francisco, the U.S. government validated the old Mexican title to Rancho El Tejon and issued the patent in 1863. The patent relegated the reservation Indians to the status of squatters on someone else's property — and that someone was none other than the crafty E.F. Beale, who purchased the land from its Mexican-American owners for $21,000. The Indians were left to fend for themselves; some found work as ranch hands on Beale's eventual 300,000-acre spread while others returned to their ancestral homes to eke out a similar existence as hired help for Americans who are celebrated in their communities today as "pioneers." — Leon Worden 2015.

PART IV.—TREATIES.

TREATY WITH THE CASTAKE, TEXON, ETC., 1851. TREATY MADE AND CONCLUDED AT CAMP PERSIFER F. SMITH, AT THE TEXAN PASS, STATE OF CALIFORNIA, JUNE 10, 1851, BETWEEN GEORGE W. BARBOUR UNITED STATES COMMISSIONER, AND THE CHIEFS, CAPTAINS AND HEAD MEN OF THE "CASTAKE," "TEXON," &C., TRIBES OF INDIANS.

A treaty of peace and friendship made and entered into at Camp Persifer F. Smith at the Texon pass, in the State of California, on the tenth day of June, eighteen hundred and fifty-one, between George W. Barbour, one of the commissioners appointed by the President of the United States to make treaties with the various Indian tribes in the State of California, and having full authority to act, of the first part, and the chiefs, captains and head men of the following tribes of Indians, to wit: Castake, Texon, San Imirio, Uvas, Carises, Buena Vista, Sena-hu-ow, Holo-cla-me, Soho-nuts, To-ci-a, and Hol-mi-uh, of the second part. ARTICLE 1. The said tribes of Indians jointly and severally acknowledge themselves to be under the exclusive jurisdiction, control, and management of the government of the United States, and undertake and promise on their part, to live on terms of peace and friendship with the government of the United States and the citizens thereof, with each other, and with all Indian tribes at peace with the United States. ART. 2. It is agreed between the contracting parties, that for any wrong or injury done individuals of either party, to the person or property of those of the other, no personal or individual retaliation shall be attempted, but in all such cases the party aggrieved shall apply to the proper civil authorities for a redress of such wrong or injury; and to enable the civil authorities more effectively to suppress crime and punish guilty offenders, the said Indian tribes jointly and severally promise to aid and assist in bringing to justice any person or persons that may be found at any time among them, and who shall be charged with the commission of any crime or misdemeanor. ART. 3. It is agreed between the parties that the following district of country be set apart and forever held for the sole use and occupancy of said tribes of Indians, to wit: beginning at the first forks of Kern river, above the Tar springs, near which the road travelled by the military escort, accompanying said commissioner to this camp crosses said river, thence down the middle of said river to the Carises lake, thence to Buena Vista lake, thence a straight line from the most westerly point of said Buena Vista lake to the nearest point of the Coast range of mountains, thence along the base of said range to the mouth or westerly terminus of the Texon pass or Canon, and from thence a straight line to the beginning; reserving to the government of the United States and to the State of California, the right of way over said territory, and the right to erect any military post or posts, houses for agents, officers and others in the service or employment of the government of said territory. In consideration of the foregoing, the said tribes of Indians, jointly and severally, forever quit claim to the government of the United States to any and all other lands to which they or either of them now have or may ever had any claim or title whatsoever. ART. 4. In further consideration of the premises and for the purpose of aiding in the subsistence of said tribes of Indians for the period of two years from this date, it is agreed by the party of the first part to furnish said tribes jointly, (to be distributed in proper proportions among them,) with one hundred and fifty beef cattle, to average five hundred pounds each, for each year. It is further agreed that as soon after the ratification of this treaty by the President and Senate of the United States, as may be practicable and convenient, the said tribes shall be furnished jointly (to be distributed as aforesaid) and free of charge, with the following articles of property, to wit: six large and six small ploughs, twelve sets of harness complete, twelve work mules or horses, twelve yoke of California oxen, fifty axes, one hundred hoes, fifty spades or shovels, fifty mattocks or picks, all necessary seeds for sowing and planting for one year, one thousand pounds of iron, two hundred pounds of steel, five hundred blankets, two pairs of coarse pantaloons and two flannel shirts for each man and boy over fifteen years old, one thousand yards of linsey cloth, same of cotton cloth, and the same of coarse calico, for clothing for the women and children, twenty-five pounds of thread, three thousand needles, two hundred thimbles, six dozen pairs of scissors, and six grindstones. ART. 5. The United States agree further to furnish a man skilled in the business of farming, to instruct said tribes and such others as may be placed under him, in the business of farming; one blacksmith, and one man skilled in working wood, (wagon maker or rough carpenter;) one superior and such assistant school-teachers as may be necessary; all to live among, work for, and teach said tribes and such others as they may be required to work for and teach. Said farmer, blacksmith, worker in wood and teachers to be supplied to said tribes, and continued only so long as the President of the United States shall deem advisable; a school house and other buildings necessary for the persons mentioned in this article, to be erected at the cost of the government of the United States. This treaty to be binding on the contracting parties when ratified and confirmed by the President and Senate of the United States of America. In testimony whereof, the parties have hereto signed their names, and affixed their seals, this the day and year first written. G. W. BARBOUR. [SEAL.] Texon:

VINCENTE, his x mark, chief. [SEAL.] Castake:

RAFAEL, his x mark, chief. [SEAL.]

San Imirio:

JOSE MARIA, his x mark, chief. [SEAL.] Uvas: ANTONIO, his x mark. [SEAL.] Carises:

RAYMUNDO, his x mark, chief. [SEAL.] Buena Vista: APOLONIO, his x mark, chief. [SEAL.] Sena-hu-ow:

JOAQUIN, his x mark, chief. [SEAL.] Holo-cla-me:

URBANO, his x mark, chief. [SEAL.] Soho-nuts:

JOSE, his x mark, chief. [SEAL.] To-ci-a:

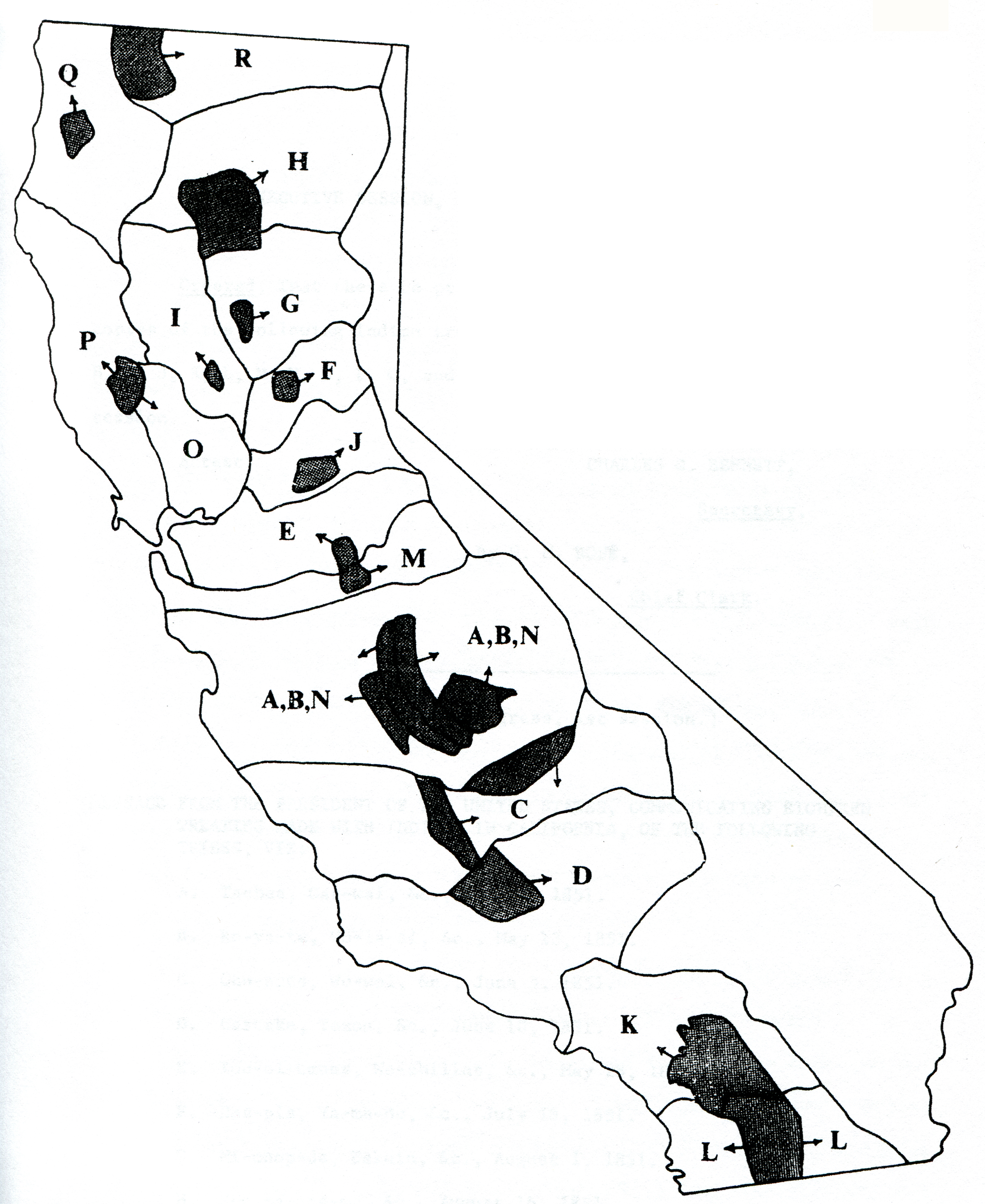

FELIPPE, his x mark, chief. [SEAL.] Hol-mi-uh: FRANCISCO, his x mark, chief. [SEAL.] Signed and sealed in duplicate, after having been read and fully explained in the presence of— H.S. BURTON, Interpreter. KIT BARBOUR, Secretary. W.S. KING, Assistant Surgeon, United States Army. J.H. LENDRUM, Brevet captain, third artillery. J. HAMILTON, Lieutenant, third artillery. H.G.J. GIBSON, Second lieutenant, third artillery. WALTER M. BOOTH. Webmaster's note: Camp Persifer F. Smith became the Tejon-San Sebastian Indian Reservation. The Eighteen Unratified Treaties of 1851-1852 Between the California Indians and the United States Government. By Robert F. Hiezer Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University 1972. Between April 29, 1851, and August 22; 1852, a series of eighteen treaties "of friendship and peace" were negotiated with a large number of what were said to be "tribes" of California Indians by three treaty Commissioners whose appointments by President Millard Fillmore were authorized by the U.S. Senate on September 29, 1850. Eighteen treaties were made but the Senate on July 8, 1852 refused to ratify them in executive session and ordered them filed under an injunction of secrecy which was not removed until January 18, 1905 (Ellison 1922-1925). A detailed account of the whole matter of the appointment of the three Commissioners (George W. Barbour, Redick McKee and O. M. Wozencraft), their travels and an analysis of the actual nature of the groups listed as "tribes" has been prepared (Heizer and Anderson, n.d.) and will, I hope, some day be published. C. Hart Merriam in 1926 prepared, at the request of the Subcommittee of the House of Representatives Committee on Indian Affairs, a detailed identification of what he called "alleged tribes" signing the 18 treaties. His working papers are filed in the C. Hart Merriam Collection (identified more fully in the appended references: Merriam Collection [1926]). A similar and wholly independent analysis of this sort was made in 1955 for the Plaintiff's counsel in the Indian Claims Commission hearings on Dockets 31/37. This was introduced as Exhibit ALK-8. A copy of this analysis with a map (Heizer [1955]) is filed as Ms. No. 443 in the archives of the Archaeological Research Facility, Department of Anthropology; University of California, Berkeley. Use of both documents is presently restricted. The texts of the unratified treaties were made public on January 19, 1905 at the order of the U.S. Senate which met in executive session on that day in the Thirty-second Congress, First Session. The treaties were published subsequently several times in connection with hearings held by the Subcommittee of the Committee on Indian Affairs, H.R. But copies of the treaties are somwhat difficult to find in the mountains of Senate and House documents published by the Government Printing Office, and it is hoped that the present partial reprinting may make their contents more readily available.[1] The first and second treaties ("M" and "N") were negotiated by the Commissioners acting together as a board. But the urgency of the matter, difficulties of treating with Indians over such a large area, and the slownness involved in the three men acting as a board, indicated the desirability of each Commissioner assuming responsibility for a large area so that the state could be covered more rapidly. As a result, and because they could not informally agree on who was to be responsible for which area, the Commissioners drew lots. Barbour arranged for treaties "A"-"D". Wozencraft arranged 8 treaties ("E"- "L". and McKee for four ("O"-"R"). The treaties differ somewhat in their wording, but they are essentially all the same. We reprint here in full the first two treaties made ("M" and "N") and one of McKee's treaties ("O"), one of Barbour's ("C") and one of Wozencraft ("K") which was the latest of the eighteen. For the rest we reprint only Articles 3 or 4 which define the area which was to be "set apart and foreve held'for the sole use and occupancy of said tribes of Indians", the tribal designations, native representatives and the American participants. The reader can, without much difficulty, learn the content of the Articles which are here omitted. These deletions are indicated by an ellipsis in the center of the page. Some treaties (for example "A"-"D") were "signed" by Indians who, almost without exception, had Spanish given names. We may assume that the treaty was read to them in Spanish by an interpreter who was attached to the treaty-making party, and that the provisions in the treaty were understood by the signatories. On the other hand~ a number of treaties were "signed" by Indians who did not have Spanish given names and who, for the most part, probably did not know either Spanish or English. In some of these instances, it seems highly unlikely that the so-called interpreters knew the several native tongues of the people who were being parlayed with. And while there may have been some kind of communication, there is great probability that the literal wording of the treaties often was not, and indeed could not be, made intelligible to the Indians present.[2] But the distance between theory and practice went even further. None of the Commissioners had any knowledge whatsoever of California Indians or the cultural practices, especially those regarding land ownership and use. As treaty makers they were under orders to make certain arrangements with California Indian tribes. As they moved with their trains through the state they made Camps,[3] sent out the word that the treaty-making party was anxious to talk with the local peopie, visited Indians in villages and invited them to attend treaty-making session. Some Indians were suspicious and refused to attend, with the result that troops might discipline them.[4] Every group met with is listed as representing a "tribe". We do not know whether the Commissioners were aware of the true nature of the named groups which they were dealing with. George Gibbs who accompanied Redick McKee seemed to be conscious of the error that was being made in assuming that any named was a tribe (Gibbs 1853:110). We know today that most of the so-called tribes were nothing more than villages. We can also assume that men listed as "chiefs" were just as likely not to be chiefs, or at least tribelet heads who are called chiefs by anthropologists. Further, since land was owned in common, even chiefs had no authority to cede tribelet or village lands. Rarely, if ever, in United States history have so few persons without authority been assumed to have had so much, and given so much for so little in return to the federal government. The three Commissioners did not have the slightest idea of the actual extent of tribal lands of any group they met with. Their orders were to secure Indian land title to California, and they managed to do this to their satisfaction by making treaties with some Indians and then dividing all of California west of the Sierra-Cascade crest into eighteen unequal cession areas which, happily, quite covered the entire region. If the Commissioners had made 12 treaties, the ceded areas would have been larger; if they had made 30 treaties the areas would have been smaller. Taken all together, one cannot imagine a more poorly conceived, more inaccurate, less informed, and less democratic process than the making of the 18 treaties in 1851-52 with the California Indians. It was a farce from beginning to end, though apparently the Commissioners, President Fillmore and the members of the United States Senate were quite unaware of that. The alternative is that all of these were simply going through motions in a matter which did not in the slightest degree really concern them. What better evidence of the latter possibility do we require than the fact that the Senate rejected on July 8,1852 the very treaties it had itself authorized and appropriated funds for their negotiation on September 29, 1850. The 18 California treaties are listed in the chronological order of their signing by Royce (1899). He provides a map (Royce: 1899, P1. CXIV) showing the area supposedly ceded by each treaty and the lands which were to be reserved "for the sole use and occupancy forever". For some earlier Indian treaties, without exception equally ludicrous and dishonest in their intent, see Heizer and Hester (1970), and for a general discussion of treaty-making with California Indians see Heizer ([1972]). Author's footnotes. 1. The present reprint is taken from a copy in teh author's possession of the documents and treaties originally "printed in confidence for the use of the Senate" in 1852 and ordered reprinted on January 19, 1905, teh day after the injunction of secrecy was removed. No attempt has been made to correct the numerous inconsistencies and obvious misspellings in the official version of 1905. These are due in part, no doubt, to the difficulty of the GPO compositor to read the handwriting of Barbour, McKee and Wozencraft or the secretary of two of the commissioners who, curiously enough, usually bore the same surname as the commissioner for whom he was working. Nepotism, at least in Gold Rush times, was not an issue. 2. Gibbs (1853:116), who accompanied McKee, reports of the Northern Pomo near Willits: "We remained in this camp two days. A considerable number of men were brought in, but all attempts to assemble their families served only to exciet their suspicions. In fact, the object of the agent, in the process of double translation through which it passed, was never fairly brought before them. The speeches were first translated into Spanish by one, and then into the Indian by another; and this, not to speak of the very dim ideas of the last interpreter, was sufficient to prevent much enlightenment under any circumstances. But the truth was that the gentleman for whose benefit they were meant by no means comprehended any possible motive on our part but mischief. That figurative personage, the great father at Washington, they had never heard of. They had seen a few white men from time to time, and the encounger had impressed them with a strong desire to see more, except with the advantage of manifest superiority on tehir own part. Their earnest wish was clearly to be left alone." A little further north, Gibbs (op. cit.:119) notes that "Quite a number of Indians were assembled and presents distributed, but no treaty attempted; for our Clear Lake interpreter, although able to comprehend them, could not explain freely in turn.#&34; Among the Wiyot lf lower Eel River, Gibbs (pg. 130) notes, "As it had become that nothing could be effected with the Indians present, for want of interpreters, it was concluded to break up camp the next day, and pressed on." It would be interesting to know whether the several treaties negotiated by McKee were fully understood by all of the individuals signing as native representatives of their tribes. It will be noted that not a single Indian actually signed his name — without exception each made his "mark." It is probable that there were among the people who were treated with, on the assumption that they were the legal representatives of their groups, not a single literate individual. 3. Each Camp where a treaty was made was named by the Commissioner in charge (or by the Commissioners acting as a board in the case of treaties "M" and "N") unless, of course, the treaty was made at an already named place such as Bidwell's Ranch (treaty "G"), Temecula (Treaty "K"). etc. 4. The Daily Alta California newspaper for May 10, 1851, ran an article on the progress of the treaty making then going on, based on interviews with two of the Commissioners (probably Barbour and Wozencraft). Referring to the treaty-making session with the groups signing treaties "A" and "N," the article states, "There are parts of 2 or 3 tribes which could not come in to treat. Some of these, it is understood, are factions of the Chow-chil-lies. The Commissioners finding it impossible to treat with them, Major Savage with 3 companies moved against them, came up with only a river between, and had a skirmish, killing 2 or 3 of them." Author's bibliography.

Heizer, R.F. (1955). Analysis of "tribes" signing the 18 unratified 1851-52 California treaties. Preface by A.L. Kroeber. Prepared for use in Dockets 31/37,

Indian Claims Commission. Ms. No. 443 Archaeological Research Facility, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley. (Includes map, scale 1:1,000,000,

showing actual territory controlled by the identifiable "tribal" groups).

— (1972). Treaties. Article to appear in Vol. VIII of Handbook of North American Indians. Smithsonian Institution.

Heizer, R.F. and G.O. Anderson (Ms). The Eighteen Unratified Treaties of 1851-52 With the California Indians. (Ms. in possession of R.F. Heizer.)

Heizer, R.F. and T.R. Hester (1970). Names and Locations of Some Ethnographic Patwin and Maidu Villages. University of California Archaeological Research Facility,

Contribution No. 9:79-118. Berkeley.

Ellison, W.H. (1922). The Federal Indian Policy in California, 1846-1860. Mississippi Valley Historical Review 9:37-67.

— (1925). Rejection of California Indian Treaties: A Study in Local Influence on National Policy. Grizzly Bear Vol. 36, No. 217 (May pp. 4-5);

No. 218 (June pp. 4,5,7); No. 219 (July pp. 6-7).

Merriam Collection (1926). Analysis of Indian "tribal" names appearing in the 18 unratified California treaties of 1850-52. C. Hart Merriam Collection,

Archaeological Research Facility, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley. Filed under "Indian Welfare."

Royce, C.C. (1899). Indian Land Cessions in the United States. Bureau of American Ethnology, Annual Report No. 18, Part 2.

|

Unratified Treaty 1851

Woodcut 1853

Ex-Reservation Church, Late 1800s

Indian Home & Orchard, Late 1800s

Indian Man, Woman, Child, Dog, Oak Tree 1888

Purpose of Fort Tejon & San Sebastian Indian Reservation (Wilke-Lawton 1976)

Kitanemuk Mythology: Coyote Kidnaps Mountain Lion's Sons

PB64811

PB65763

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.