Year of the Rat: Acton Gold Miner vs. San Francisco's Bubonic Plague.

When the Black Death reached America's shores, Henry Gage made sure it wouldn't tarnish the Golden State's image.

|

There is no invisible bug that's mysteriously killing people in San Francisco. It's a "fake plague." If anyone is dying mysteriously, it's only Chinese immigrants. Certainly the white population is immune. The only way the plague could get here is if the stubborn East Coast scientist with his fancy microscopes brought it from his laboratory and planted it on cadavers to spread it intentionally. Any newspaper that reports otherwise should be severely punished under the law.

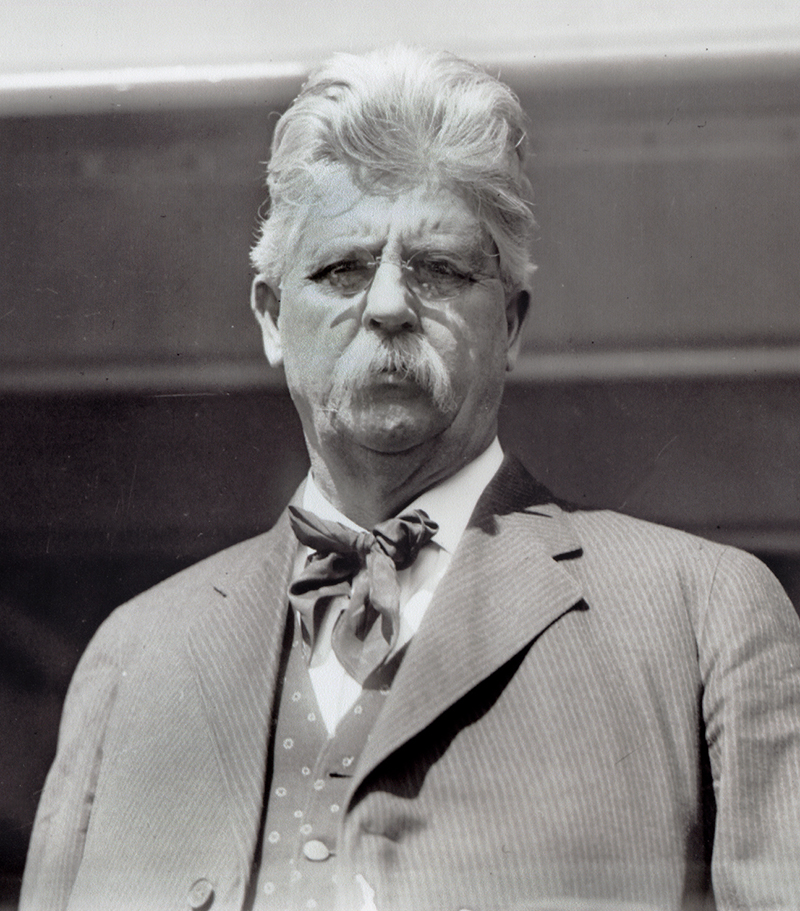

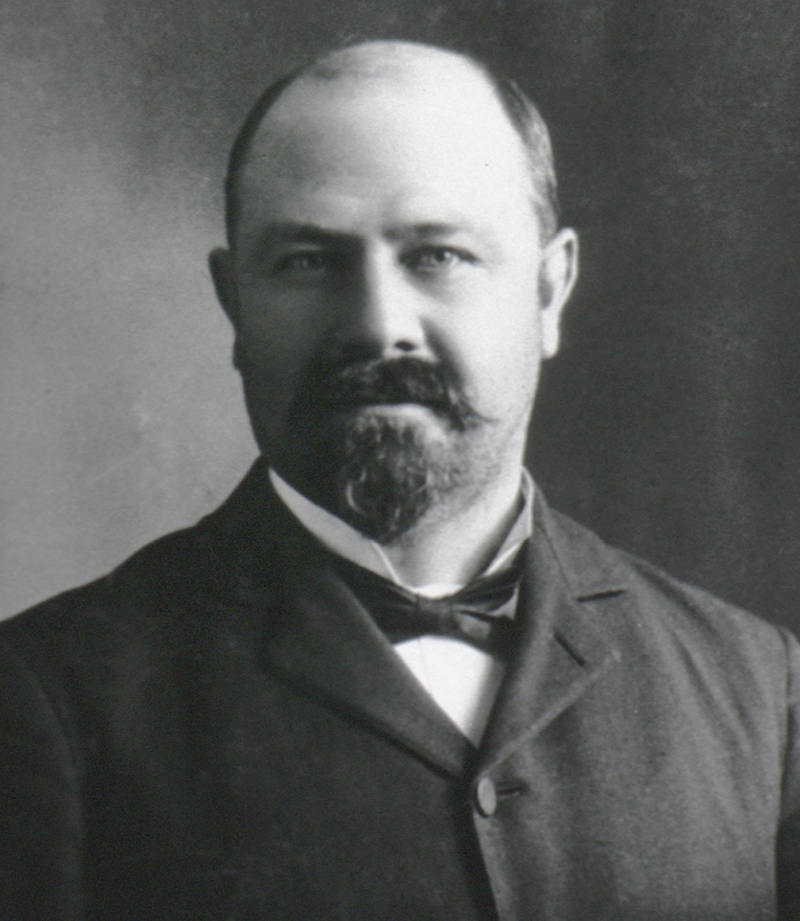

So said Henry Tifft Gage, the owner of the Red Rover, New York, Puritan and other gold mines in Acton who became governor of California in 1899. The state Legislature backed him up by criminalizing "fake plague" news in 1901. Today, some researchers credit Gage's decision to put San Francisco's reputation and business interests ahead of public health, and his success at thwarting federal intervention efforts, for the fact that the bubonic plague still exists in America, where it hadn't previously been known. Today's version, although rare — roughly 7 confirmed U.S. cases per year — is believed to be the same strain.[1] With a century's hindsight, we know the newspapers were correct to report the findings of the stubborn scientist from the Marine Hospital Service, Joseph James "Joe" Kinyoun (1860-1919), whose one-man, one-room laboratory on Staten Island in 1887 would morph into the federal government's National Institutes of Health in 1912. "Kinyoun had predicted plague's eventual arrival in the United States as early as 1895 and had begun a plague research program in 1896," according to a publication[2] coauthored in 2012 by Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., director since 1984 of NIH's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Arrival. In 1899, Kinyoun's boss, Surgeon General Walter Wyman, sent him to the quarantine station of Angel Island in the port city of San Francisco — although it was at least partially to get him as far away as possible, as the two men didn't get along. Kinyoun arrived just in time to hear rumors that a "plague ship" was en route from Honolulu. The rumors proved false, but they weren't without merit. In December 1899, the plague arrived in Honolulu, presumably on rat-infested Chinese merchant ships. (Hawaii had become a U.S. territory the previous year.) The 10,000 residents of Honolulu's Chinatown were sealed off. When a white teenager contracted the disease and ultimately died, local authorities started burning down apartment buildings that housed the city's Chinese, Japanese and ethnic Hawaiian residents — the same way Londoners had eradicated the plague in 1666 in what turned into the Great Fire of London. (Oops.) Then as now, it seemed to work.[3]

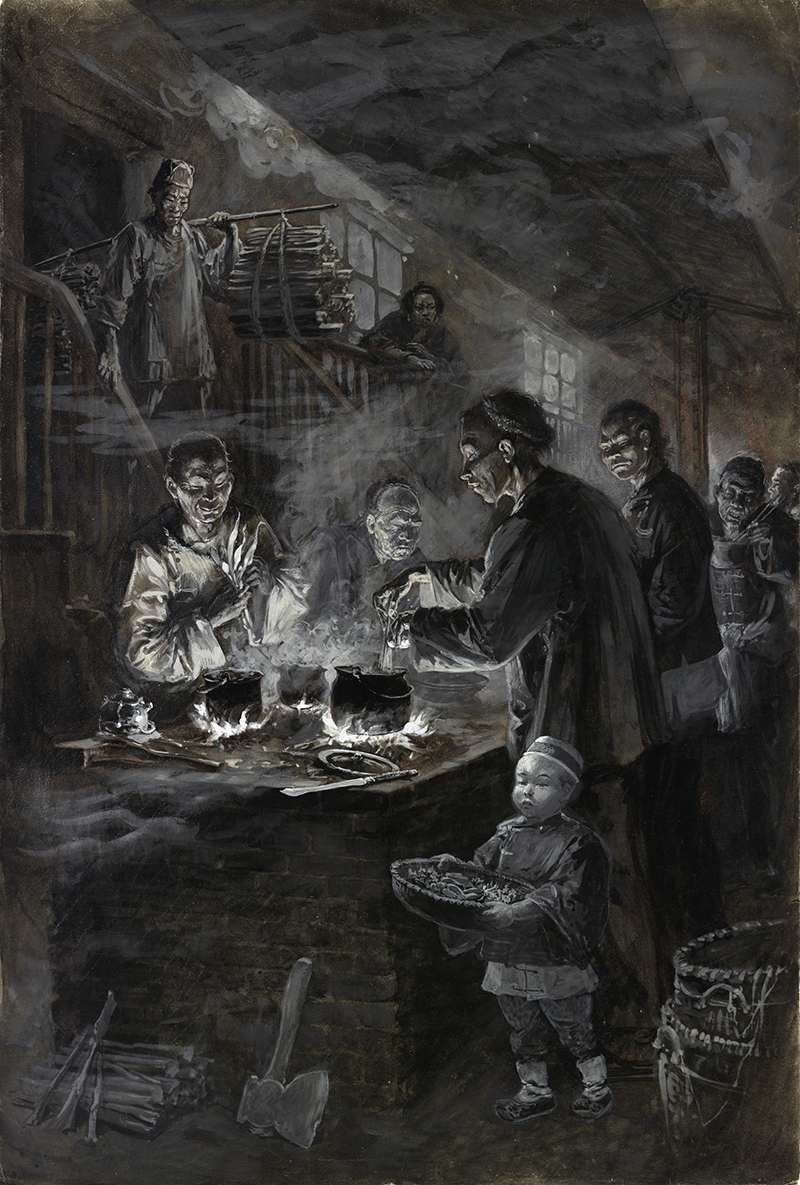

Meanwhile in San Francisco, Kinyoun began quarantining arriving ships from the four known "plague ports" of Honolulu, Sydney, Hong Kong, and Kobe, Japan. But then, on March 6, 1900, a 41-year-old lumber salesman named Wong Chut King died a gruesome death from disease. His body lay in an undertaker's shop at 814 Clay Street in the Chinatown section, and the police needed to establish cause of death. Kinyoun, with his fancy microscopes, confirmed it as the first U.S. death from the bubonic plague. It touched off a political war.

San Francisco's mayor and Board of Health immediately placed Chinatown within a police cordon sanitaire but backed off in the face of legal challenges by a Chinese cultural association allied with California businessmen and politicians. Seemingly everyone got into the fights that followed, with local and national medical and public health experts on one side, and California's governor, allied politicians, Chinese and Western businessmen, and "muckraking" newspapers on the other.[4] On May 15, with 11 confirmed cases among the Chinese population and many more suspected to be in hiding, Kinyoun declared it an epidemic. Even as the number of cases mounted, when Kinyoun linked the disease to rats, he was lampooned by most San Francisco newspapers, which were allied with Henry Gage. (Both Gage and the city of San Francisco were allies of the railroads, which were major players in California politics.) William Randolph Hearst's Examiner was the outlier, calling the plague a plague. "Plague epidemiology was poorly understood ... although an association with rats was known and flea transmission postulated".[5] Kinyoun's own boss, Wyman, didn't believe the rat hypothesis; he thought urine and feces were the principal vectors.

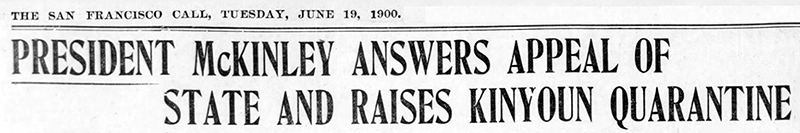

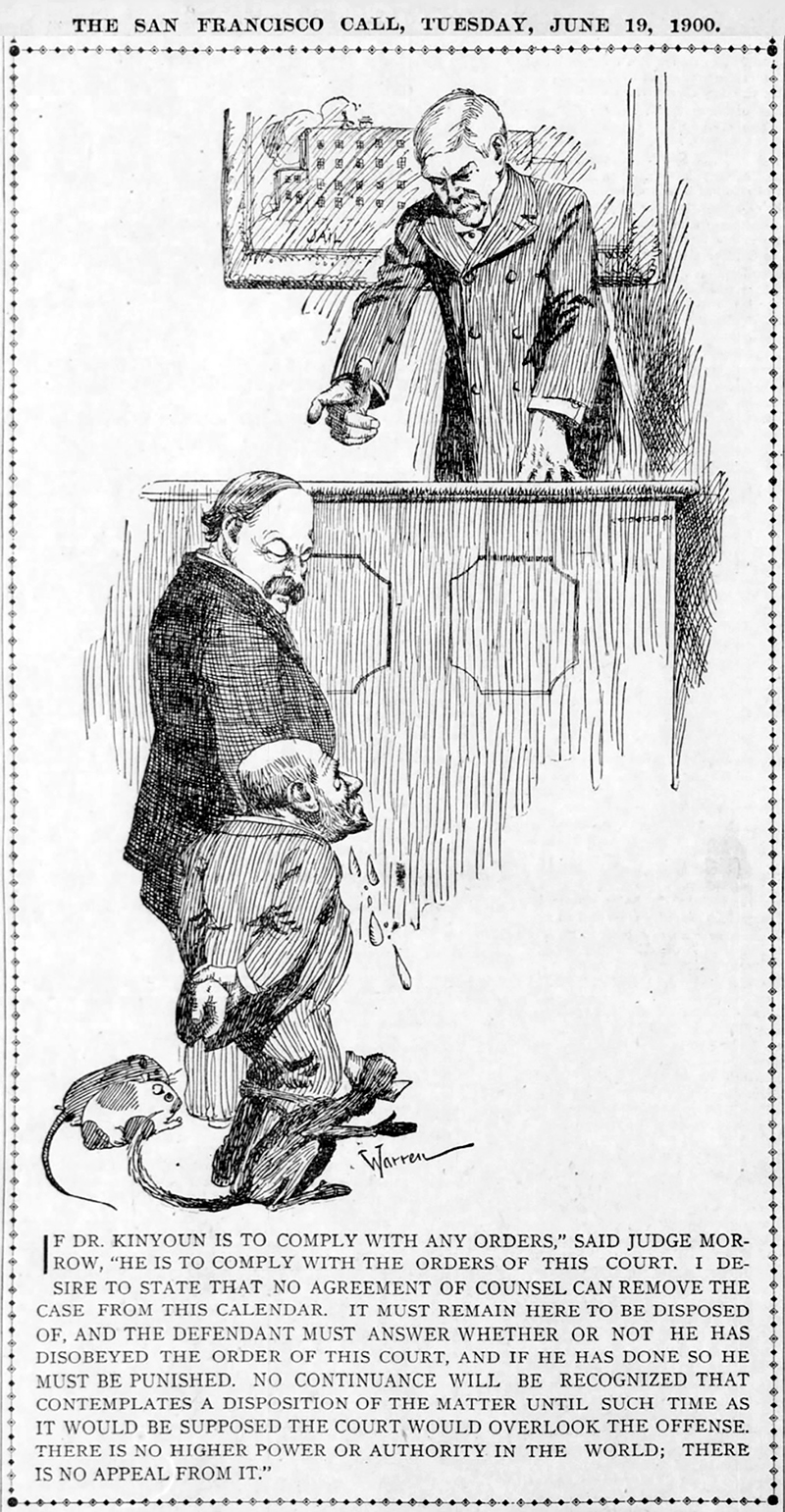

But in the public sphere, Gage's politicking fell on receptive ears. "The President of the United States has declared that after thorough investigation and a consideration of complete reports from California, he is convinced that there is no plague in the state and never has been," the San Francisco Call reported in June 1900. McKinley lifted Kinyoun's quarantine.[7]

That same day, Kinyoun stood before a federal magistrate in San Francisco on a contempt charge for allegedly failing to comply with an injunction barring his health-certificate requirement for travelers. Kinyoun said he was no longer requiring them but failed to tell the Southern Pacific Railroad. Kinyoun was eventually acquitted, and the judge, William W. Morrow, later asked him to rat-proof his house with a new rodenticide.[8] Seven months had gone by without any significant disease prevention measures in place when Gage, in his January 1901 State of the State address, told Sacramento lawmakers how he arrived at the inescapable conclusion that there was not now and never had been an incidence of bubonic plague in San Francisco[9]:

Intimations were thrown out in the months of March and April last that the dreadful bubonic plague existed in the Chinese quarters of San Francisco. Secret consultations and alleged investigations were had by said city officials in conjunction with the federal quarantine officer. [The question became:] Could it have been possible that some dead body of a Chinese had innocently or otherwise received a postmortem inoculation in a lymphatic region by someone possessing the imported plague bacilli, and that honest people were thereby deluded? [..] Thereafter, upon the 13th of June 1900, my labors occupying weeks were completed, the different medical views maturely considered, and I was satisfied beyond all reasonable doubt that the bubonic plague had not been in the Chinese quarter of San Francisco, nor in any other part of the city, nor in any part of the state. Gage — gold miner, corporate lawyer, politician by profession and experience — then shares his first-hand knowledge of infectious diseases:

I personally know, with respect to some of the same subjects, officially reported as plague-stricken, that where lymph was taken from such subjects, under my direction, and most carefully watched and handled, no such results were produced under the microscope or upon animals as those reported by Dr. Kinyoun. [...] At all events it must be remembered that Dr. Kinyoun ... never had any experience with the disease proper, his experience being derived wholly from books and laboratory work, and not from practice among victims of the plague. Certain to delight the Chronicle and perplex the Examiner, Gage calls on the Legislature to muzzle the Fourth Estate in the name of commerce:

"I would not desire, were it possible under our Constitution and laws, for a censorship to be established over the press, notwithstanding some abuses. I am, however, firmly of the opinion that legislation is necessary to protect the people in the conduct of their business and the sale of their products and commodities. Such acts, causing great wrongs to the state by an individual or a corporation, should be declared criminal, and severe punishment should be meted out to such offenders. I suggest, therefore, that it should be declared a felony for any person or corporation to publish ... any false report of the presence of bubonic plague within this state, [whether the report be published inside or outside of California]. [...] The people cannot permit their business and industries to be checked, injured or destroyed at the mere whim and caprice of a private person or private corporation conducting a newspaper, which is capable of disseminating far and wide malicious or false reports respecting the condition of the public health of the state. E-rat-ication. Behind the scenes, the scientists who'd been sent by Washington confirmed what Kinyoun had known all along: It was the plague. Gage and company "suppressed the report for several months. [The Treasury secretary] countered with a threat to deprive California of revenue by closing Army headquarters there and diverting San Francisco-bound Philippine transports to Puget Sound if it did not act upon the [findings]"[10]. In the end, Gage allowed federal health authorities to take over quarantine and plague control, but only if the government agreed to remove Kinyoun from his post — which it did. Kinyoun's successor, Rupert Blue, had to deal with the same forces that exiled Kinyoun. The surgeon general, Wyman, still thinking "filth" was the principal vector, ordered a general cleanup. It certainly helped, if only to frustrate the rats. Blue moved his lab to Chinatown and orchestrated a citywide cleanup in 1903 that involved tearing down shacks, soaking cellars with carbolic acid, laying asphalt sidewalks and trapping rats. Henry Gage wasn't even nominated for reelection by his party that year. But not because of his fumbling of the bubonic plague epidemic in San Francisco. That was rather well received by the public. Instead, it had to do with his reluctance to confront labor organizers in San Francisco and his continued support of the railroads, which were growing increasingly unpopular as they extorted tolls in the form of cash and land from cities in exchange for new roads and depots.[11] Meanwhile, Blue's efforts were paying off. By early 1905, the problem seemed to have gone away. But then the city was flattened in 1906, and a second wave hit. Blue was exterminating up to 13,000 rats a week in 1907. He found that 1.5 percent of them were infected; 2 percent was the threshold for declaring a pandemic.[12] Epilogue. A century later, if it's odd to think the public and other political leaders would take the word of an Acton gold miner and lawyer over the federal government's infectious disease specialists, then, besides simply not wanting it to be true: One, infectious diseases were not well understood, especially by the lay public. Two, the epicenter of the problem was in Chinatown, which had little political leverage. Three, by the numbers, there were relatively few confirmed deaths. In eight years, there were 280 confirmed cases and 172 confirmed deaths, of which 65 came in the second wave, after the earthquake. Why didn't the bubonic plague inflict mass death in San Francisco as it had in Asia? Dumb luck. According to author David K. Randall, it was the type of flea. San Francisco's most common flea was a European species, Ceratophyllus fasciatus, which injects less bacteria from its gut than the common Asian flea, Pulex cheposis. Randall writes[13]: "The slow spread of the disease — a phenomenon that led the city to doubt Kinyoun's warnings and call the epidemic a fake ploy by corrupt health officials — had hinged on the stomach of a flea, a lucky quirk that spared an untold number of lives." And yes, 1900 was the Chinese Year of the Rat.

1. Chase, Marilyn. "The Barbary Plague: The Black Death in Victorian San Francisco." New York: Random House Inc., 2004. 2. "Dr. Joseph Kinyoun: The Indispensable Forgotten Man" by David M. Morens, M.D., Victoria A. Harden, Ph.D., Joseph Kinyoun Houts, Jr. and Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., National Institutes of Health, 2012. 3. Randall, David K. "Black Death at the Golden Gate: The Race to Save America from the Bubonic Plague." New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2019. 4. Morens, et al. 5. Ibid. 6. Ibid. 7. San Francisco Call, June 19, 1900. 8. Morens, et al. 9. As published in the Los Angeles Times, January 9, 1901. 10. Morens, et al. 11. Quinn, Mildred. "California Governors, Past and Present." Newport Beach: Franklin Publications Inc., 1970. 12. Randall 2019. 13. Ibid.

|