|

|

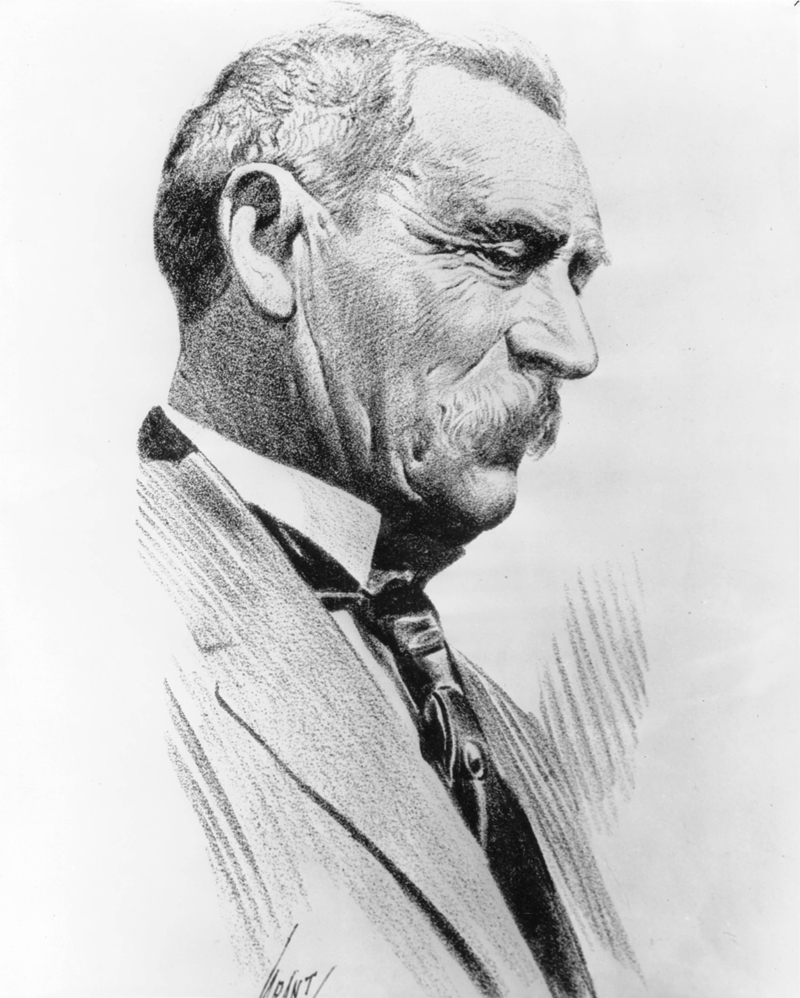

Chief Engineer, L.A. Bureau of Water Works and Supply

Click image to enlarge William Mulholland, chief engineer, Los Angeles Bureau of Water Works and Supply (LADWP). Undated pencil or charcoal sketch, 26x21cm(?). Artist unknown (partial signature visible). Probably post-dates the 1928 St. Francis Dam Disaster. California Historical Society Collection. It can be fairly said that William Mulholland engineered the growth of Los Angeles, for he brought to it the one commodity this dusty, thirsty pueblo would need to support the influx of millions of new residents — water. Chief engineer for the city of Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, Mulholland was a key player in the construction of the Panama Canal, the Colorado Aqueduct, Hoover Dam and the Los Angeles Aqueduct — the latter taking water from the farmland of the Owens Valley and piping it to the growing metropolis. As part of the project, Mulholland designed and oversaw construction of the St. Francis Dam, a 600-foot-long, 185-foot-high curved, concrete gravity dam capable of holding 38,000 acre-feet (12.5 billion gallons) of water high above Saugus in San Francisquito Canyon. The reservoir would meet the needs of Los Angeles for about a year, should the Owens Valley farmers, who often sabotaged the project — or the Elizabeth Tunnel, which crossed the San Andreas fault to the north of the dam and "Powerhouse No. 1" — threaten the flow of water to the City. Dam construction started in August 1924; water began to fill the reservoir on March 1, 1926. Two months later the dam was completed. Mulholland's empire came crashing down at three minutes before midnight on March 12, 1928. Half of the dam suddenly collapsed. An immense wall of water rushed down the canyon at 18 miles per hour, totally decimating the concete-and-steel "Powerhouse No. 2" pumping station as well as the Frank LeBrun Ranch, the Harry Carey Ranch and Trading Post, and everything else that stood in the way. Floodwaters met the Santa Clara River at Castaic Junction and headed west toward the Pacific Ocean. The communities of Piru, Fillmore, Santa Paula, Saticoy and much of Ventura lay in waste by the time the water, mud and debris completed a 54-mile journey to the ocean at 5:25 a.m. on March 13th. At dawn's early light, an estimated 431 people lay dead (Stansell 2014). Some bodies were buried under several feet of earth and were still being discovered in the 1950s. In fact, remains believed to belong to a dam victim were found in 1994. Several investigations followed, including a hastily prepared government study released five days after the disaster, which attributed the failure to the construction of the west abutment on top of the fault contact between the Sespe conglomerate and the Pelona Shist. Later study discounted the theory and revealed that the east abutment was situated on top of an ancient paleo mega-landslide — something Mulholland did not know. (Perhaps he should have known; a report by geologist Dr. Bailey Willis, published June 25, 1928, three months after the dam failure, mentioned the ancient landslide.) Contributing factors may have been the base of the dam, which may not have been as thick as thought, and the top of the dam, where 15 feet of concrete were added that apparently were not in the engineering plans. The disaster that ended the career of the famous engineer was the second-worst in California history, behind only the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906 in terms of lives lost.

LW2739: 19200 dpi jpeg | California Historical Society Collection at University of Southern California, Catalog No. CHS-6621. |

SEE ALSO:

Transcript of Coroner's Inquest

Hall of Justice 1928

Verdict of Coroner's Jury

Arizona Report 1928

Popular Science 1964

• Rippens Story of Dam Disaster (1998)

Vital Lesson for Today (ASDSO 2018)

At Dam Site 3-14-1928

With Van Norman at Dam Site 3-15-1928

Coroner's Jury Inspects 3/1928

Hall of Justice 1928

Fountain 1940s

Aqueduct Memorial Garden Opens at Mulholland Fountain: Story 10-23-2013

Mulholland Fountain & Aqueduct Garden: Photo Gallery 11-10-2013

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.